By Joe Born

1. Introduction

By presenting actual calculation results from a specific feedback-system example, the plots below will put some graphical meat on the verbal bones of Nick Stokes’ recent “Demystifying Feedback” post.

I heartily agree with the main message I took from Mr. Stokes’ post: although some climate equations may be similar to certain equations encountered in, say, electronics, it’s not safe to import electronics results that the climate equations don’t intrinsically dictate. But I’m less convinced that Mr. Stokes succeeded in removing the mystery from feedback. I’m reminded of what a professor said over a half century ago in one of those compulsory science courses: “Don’t just scope it out; work it out.”

What the professor meant is that we humans tend to overestimate our abilities to intuit an equation’s implications. Actual calculations routinely reveal that the equation doesn’t mean what we had thought. That can be true even of equations as simple as the equilibrium scalar feedback equation at issue here.

Except for folks who have significant experience in working through feedback systems, for example, readers may not take as much meaning as might be hoped from abstract statements such as the following:

“One thing that is important is that you keep the sets of variables separate. The components of x0 satisfy a state equation. The perturbation components satisfy equations, but are proportional to the perturbation. You can’t mix them. This is the basic flaw in Lord Monckton’s recent paper.”

Working through an actual example could provide more insight. And an occasion to do just that is presented by Christopher Monckton’s claim that feedback theory imposes (what we’ll call) the entire-signal rule:

“[S]uch feedbacks as may subsist in a dynamical system at any given moment must perforce respond to the entire reference signal then obtaining, and not merely to some arbitrarily-selected fraction thereof.”

Critics like Mr. Stokes and Roy Spencer have disputed that rule. And, indeed, there are good practical reasons in climate science for treating feedback as something that’s responsive only to changes rather than to entire quantities. Yet, if we instead accept Lord Monckton’s entire-signal rule for the sake of argument and work through its implications, we can gain more insight into questions like what “you can’t mix them” really means.

So in what follows we’ll accept that rule and define an example feedback system in which the feedback responds to the entire output rather than only to perturbations. And we’ll observe the rule’s implications by working through the system’s responses to a range of inputs.

In the process we’ll juxtapose the small- and large-signal versions of metrics like “feedback fraction” and “system-gain factor” to reveal the latent ambiguities with which they afflict feedback discussions. We’ll also see examples of how easily the feedback equation, simple though it is, can be misinterpreted.

2. Background

First we’ll use the following plot to place Mr. Stokes’ post in context.

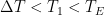

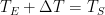

Lord Monckton views the climate system’s equilibrium temperature as a function of the value

it would have if there were no feedback. By way of accepting for the sake of argument “all of official climatology except what we can demonstrate to be false,” Lord Monckton has adopted values we’ll call

as the equilibrium temperature corresponding to 1850’s carbon-dioxide concentration and

as what it would have been had there been no feedback. The point labeled “Pre-Industrial” in the plot above represents those values. The point labeled “IPCC Prediction” results from increasing those values by the “official climatology” ECS value,

, and the value

it would have had without feedback. (Equilibrium climate sensitivity (“ECS”) is the increment by which doubling carbon-dioxide concentration would increase the equilibrium global-mean surface temperature.)

Observational studies like Lindzen & Choi 2011 have led many of us to believe that ECS is actually much lower than that—if there really is such a thing as ECS. In a video that introduced his theory as a “mathematical proof” that ECS is low, though, Lord Monckton said of previous ECS-value arguments that they had “largely been a competition between conjectures.” He may agree with researchers like Lindzen & Choi, he said, but “they can’t absolutely prove that they’re right.” In contrast, “we think that what we’ve done here is to absolutely prove that we are right.”

By in essence projecting those points to the no-feedback, line, he eventually came to describe climatology’s error as failing to recognize that some of the feedback is response to the emission temperature. And he came to express his proof in the form of the above-mentioned entire-signal rule, of which he said:

“Once that point—which is well established in control theory but has, as far as we can discover, hitherto entirely escaped the attention of climatology—is conceded, as it must be, then it follows that equilibrium sensitivity to doubled CO2 must be low.”

In the passage quoted above, Mr. Stokes’ post contested that theory. So we’ve added a hypothetical curve to the plot to illustrate what high-ECS proponents might think. But to represent substantial feedback to the emission temperature the curve passes to the left of the emission-temperature point on the no-feedback,

line in compliance with the entire-signal rule.

3. “Underlying Mathematics”

In a reply to Mr. Stokes’ post Lord Monckton diagrammed his version of the equilibrium scalar feedback equation. That equation seems simple enough, but he wrote of its block diagram that “one can only really understand how it works if one also has a grasp of the underlying mathematics.”

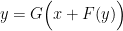

However, by treating the (counterfactual) no-feedback temperature as the input, Lord Monckton’s equation

hides the underlying relationship between the output and forcing. To avoid the resultant loss of insight we’ll therefore deal primarily with the forcing relationship, but we’ll map the results to Lord Monckton’s counterfactual-temperature relationship.

For this purpose we’ll simply adopt the more-general notation that the system produces a response to a stimulus

; we won’t try to straddle his temperature-input notation and the conventional forcing-input notation

. If we were simply to replace the conventional perturbation values with entire values, we’d thereby have:

That is, the output temperature would simply be the product of a gain

and the sum

of the input forcing

and output-dependent feedback

. (The notation for the ratio of feedback to output will be

to distinguish it from Lord Monckton’s feedback fraction

.) The following explicit expression for the equilibrium-temperature output

would seem to follow from elementary algebra:

This is all seemingly simple. But even seemingly simple equations can be hard to interpret. Moreover, Lord Monckton’s theory requires that we deal with entire quantities rather than just small perturbations, so we can no longer ignore nonlinearities.

Therefore, since the formulation may suggest that on the contrary

and

are constants, we’ll so rewrite the scalar system’s equilibrium equation as explicitly to allow for nonlinearity. Specifically, we’ll replace

with

and

with

:

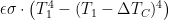

To map this forcing-input formulation to Lord Monckton’s temperature-input formulation , we will also calculate a without-feedback temperature

, where

denotes

‘s inverse function:

. Lord Monckton’s

and

respectively correspond to

and

.

4. Example-System Functions

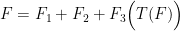

Now we reach specifics: we’ll define the functions and

in our system equation

.

In doing so we won’t attempt to match the actual climate relationship between equilibrium temperature and forcing. For one thing, no one really knows what that relationship is throughout the entire domain that Lord Monckton would have us acknowledge. To the extent that an equilibrium relationship does exist, moreover, temperature almost certainly isn’t a single-valued function unless that function’s argument is a vector of forcing components instead of the scalar total thereof we’re assuming here. (Those complications are among the reasons why focusing on perturbations is preferable.)

But the question that Lord Monckton’s purported mathematical proof raises isn’t whether we know the relationship; it’s whether, without knowing what that relationship is, high ECS values can be ruled out mathematically. So we’ll merely choose simple relationships that exhibit a high ECS value and watch for any contradictions of what Lord Monckton called “the mathematics of feedback in all dynamical systems, including the climate.”

4.1 Open-Loop Function

For our open-loop function we adopt a fractional-power relationship:

Note that with = 0.25 this function would be a fourth-root relationship reminiscent of the inverse Stefan-Boltzmann equation. As a nod toward the real-world difference between the surface temperature and the effective radiation temperature, however, we’ve instead adopted

, with

.

As we see, ‘s slope falls off with input

:

Since relates an output to an input, the plot above refers to

‘s slope as a “gain.” Of particular importance to this discussion is that the plot shows both the average slope

(large-signal gain) and the local slope

(small-signal gain). Failure to distinguish between those quantities consistently has bedeviled discussions of Lord Monckton’s theory.

Note also that we refer to both quantities as “open-loop gain”: each is a gain that the system would exhibit if there were no feedback to “close the loop.” Perhaps confusingly—but I think logically—the discussion below uses similar expressions to refer to different quantities.

Specifically, closed-loop gain will refer to the gain that results when feedback does indeed “close the loop.” Lord Monckton sometimes calls this the “system-gain factor.” And just plain loop gain will be the internal gain encountered in traversing the loop: what Lord Monckton occasionally calls the “feedback fraction.” The loop gain results from combining the open-loop gain with the feedback ratio, which we will presently introduce in connection with the feedback function.

Again, the quantity to which our open-loop function relates the output temperature

is forcing. If as Lord Monckton does we instead take the input to be the no-feedback temperature, the resultant open-loop function

is just the input itself:

; if there were no feedback, the output would be the same as the input.

4.2 Feedback Function

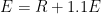

Climatologists sometimes get media attention by speaking of a “tipping point.” But the particular feedback function we chose for the Fig. 1 curve wouldn’t cause one. Since the behavior it results in thereby lacks one of feedback’s more-interesting features, we’ll instead adopt the following feedback function, which causes a tipping point not far beyond the doubled-CO2 equilibrium temperature:

where and

Note that in our feedback-function choice we differ with Lord Monckton’s critics who object that feedback can only be a response to perturbations. Like the Fig. 1 curve’s feedback function, our example, tipping-point-causing function is responsive to the entire output. To be sure, the response seems to become significant in both cases only as the temperature approaches ice’s 273 K melting point; the response approaches zero as the output temperature does. But actually working through the resultant example-system behavior near absolute zero reveals that because of the high forward gain we saw in Fig. 3 the feedback is great enough to cause instability.

Furthermore, although the example function’s value at the doubled-CO~2~ temperature approximates that of the feedback function responsible for Fig. 1, it exceeds it at temperatures very much above or below that temperature. In particular, our chosen function’s feedback to the emission temperature will be even greater than the Fig. 1 function’s.

Now, I don’t really think either of those feedback functions is like the actual climate’s feedback function. I personally don’t think the actual climate has much net-positive feedback at all.

But that’s not the point. Lord Monckton claims to have developed a mathematical proof. That means showing that accepting a high ECS value for the sake of argument would lead to a contradiction with “the mathematics of feedback in all dynamical systems, including the climate.” So the point isn’t whether we believe that premise. It’s whether accepting the premise leads us to a contradiction. And we will search in vain for contradictions among the implications of a system’s exhibiting not only a high ECS value but also a tipping point.

The plot above shows the resultant feedback ratio, i.e., the quantity that multiplies the output or increment thereof to yield our feedback function’s corresponding feedback quantity. It’s the feedback function’s average (large-signal) slope or local (small-signal) slope

, where the prime represents differentiation. Again we see that the large- and small-signal versions differ markedly; one does not approximate the other.

Different feedback-ratio functions, plotted above, result if we instead take Lord Monckton’s temperature-input view of the system. Those functions are average and local slopes of a different feedback function, of the function implied by

.

The different views’ feedback ratios are somewhat similar at the higher temperatures we’re interested in, but their low-temperature behaviors are quite different. That doesn’t mean that the temperature-input view is wrong. In fact, although I believe the forcing-input view is usually preferable, the temperature-input view may be the more-informative in the case of feedback ratio, which in the temperature-input view happens to equal that view’s loop gain (Lord Monckton’s “feedback fraction”).

5. Resultant Behavior

5.1 Closed-Loop Function

Having now defined our system’s open-loop and feedback functions, we turn to the resulting closed-loop function, i.e., to the function such that our feedback equation

implies

:

This plot illustrates the tipping point we so chose our feedback function as to cause. No (equilibrium) output values correspond to input values that exceed about 273 W/m2. That’s because any higher input value would cause the output to increase without limit: the system would never reach equilibrium. (If pressed, tipping-point partisans would presumably admit to some limit, but let’s just assume their limits are off the chart.) As we will see in due course, inputs that exceed the tipping-point input correspond to a small-signal loop gain that necessarily exceeds unity.

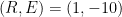

Although the output increases without limit for those values, Lord Monckton says instead that a (large-signal) “feedback fraction” greater than unity would imply cooling. One can see that it wouldn’t, though, by using Lord Monckton’s own

and for the sake of simplicity assuming a constant

= 1.1 so that the large- and small-signal values are equal. Starting with

and

, iteratively evaluate

. You’ll find that

blows up.

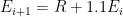

Unlike the input, the output has equilibrium values that exceed its tipping-point value, which for the output is about 301 K. The curve’s dotted portion represents them. The dots indicate that the corresponding states are unstable.

You can get an idea of what unstable means by supposing that negative temperatures have meaning in Lord Monckton’s linear system. Again assume a constant

= 1.1. If iterations start at

= (1, –10) instead of (1, 0), the output

will remain at –10: (1,–10) is indeed an equilibrium state. Nudge the input

one way or the other, though, and in accordance with the direction of the nudge the output will take off toward positive or negative infinity. Although (0, –10) is an equilibrium state, that is, it’s unstable.

The example system will similarly tend to flee the unstable states and possibly blow up. The example system is nonlinear, though, and the direction of the nudge determines whether it actually does blow up or instead falls to a stable value, i.e., from the dotted curve to the solid one.

Having seen the output behavior from the forcing-input view, let’s turn to Lord Monckton’s temperature-input view. That is, let’s consider the function such that

implies

:

This view suppresses the nonlinearity in the relationship between forcing and temperature. Since the input is simply what the output would have been without feedback—whose ratio to output is very low throughout most of the function’s illustrated domain—the output over much of the curve nearly equals the input. Toward the right, though, the output pulls away. And, just as in the previous plot, there’s a tipping point.

5.2 “Feedback Fraction”

Now we come to what is perhaps the most-consequential quantity: the loop gain, or, in Lord Monckton’s terminology, the “feedback fraction.” Here again we will see the importance of distinguishing between large- and small-signal versions.

The plot above confirms what we may have surmised from the previous plot: the loop gain is near zero over most of the function domain. But above-unity loop gains on the plot’s right impose the limit we observed on equilibrium-state input values.

Note in particular that it’s the small-signal version of the loop gain whose unity value imposes the limit; the large-signal loop gain is quite modest right up to the tipping point. So it’s important to keep track of which quantity Lord Monckton intends when he discusses the “feedback fraction.”

(Obscure technical note for feedback-theory types: Because of the high small-signal open-loop gain near absolute zero, the system is unstable in that neighborhood even though the feedback approaches zero. For the loop-gain plots we therefore used negative inputs to obtain some of the near-zero behavior, and to that end

and

were extended as odd functions into the third quadrant.)

Recall that loop gain is the gain encountered in traversing the loop. For the forcing view the large-signal loop-gain version is therefore the ratio of the output-temperature-caused feedback to the total forcing that caused the output temperature. The small-signal version is the corresponding incremental quantity

.

Since a unity value of this dimensionless quantity’s small-scale version represents the stability limit, one might think it would be the same thing in both views. If we actually work it out, though, we see there’s a difference.

For the temperature-input view the large-signal loop-gain quantity is the ratio that the feedback temperature bears to the output temperature

: it’s

, which maps to Lord Monckton’s feedback fraction

. The corresponding small-signal version is

. In this view the loop gain is the same as the feedback ratio we saw in Fig. 6.

But a comparison of the two views’ small-signal loop gains is instructive:

Although their small-signal tipping-point values are the same in both views, the different views’ loop gains otherwise differ.

5.3 “System-Gain Factor”

We finally come to closed-loop gain. This time we’ll start with Lord Monckton’s temperature-input view. In that view the large-signal version is . That version corresponds to Lord Monckton’s “system-gain factor”

. To calculate ECS’s value

, he advocates multiplying the “reference sensitivity”

by that quantity.

But by definition the quantity whose multiplication by really does yield ECS’s correct value

is instead the “secant slope”

. Even Lord Monckton seems to admit that the secant slope is the right multiplier. (Well, what he actually says is, “The disadvantage of [deriving the “system-gain factor” as a secant slope] is not, repeat not, that it is wrong, but that it is not useful. . . .”) This view’s small-signal gain

corresponds to

rather than

and therefore equals that secant slope at some point in the relevant interval 265.00 K < R < 266.05 K. As the plot above shows, that small-signal gain is about 3 times the large-signal gain in that interval: it’s about 3 times the “system-gain factor” Lord Monckton uses for his ECS calculation. So if the “secant slope” is correct—as by definition it is—then Lord Monckton’s approach greatly underestimates ECS when ECS is high.

Now, in actuality his approach probably would not result in a serious underestimate if, as many of us believe, ECS is low. That’s because a low value would not result in the great between-version difference that the plot depicts. But that fact doesn’t support Lord Monckton’s theory.

The problem is that his theory’s targets aren’t people who already believe ECS is low. He characterized his theory as a “way to compel the assent” of those who would otherwise believe ECS is high. It would compel assent, he said, because, unlike previous ECS arguments, his theory isn’t a mere conjecture; it’s a proof.

But a proof of low ECS can’t be based on assuming low ECS to begin with; that would be begging the question. Nor would the assent of someone who thinks ECS is high be compelled by an approach that greatly underestimates ECS when it is high. What could arguably compel assent is for the high-ECS assumption to result in contradictions of “the mathematics of feedback in all dynamical systems, including the climate.” That’s why we took a high-ECS system as our example: to expose any such contradictions. But we found none.

Now a point of clarification about the plot. The dotted curves mostly represent unstable equilibrium states as they did in previous plots. But here there’s an exception: the dotted black curve’s vertical segment on the right, at the maximum equilibrium-input value. That segment is merely the line between positive- and negative-infinity values: its abscissa is the value at which the closed-loop gain switches abruptly from positive to negative infinity. So no equilibrium states actually occur on that vertical segment.

It might therefore have been less distracting to omit that segment from the plot. But it provides another opportunity to point out how hard it can be to interpret even simple algebraic equations properly. The corresponding discontinuity in the hyperbola of linear-system gain ratio as a function of loop gain is the basis of Lord Monckton’s above-mentioned belief that loop gains greater than unity imply cooling:

That interpretation is wrong, of course; Fig. 8 showed us that equilibrium output temperature continues to increase beyond the transition to instability.

In the electronic-circuit context Lord Monckton has analogously interpreted that discontinuity is as being the point “where the voltage transits from the positive to the negative rail.” That interpretation is beguiling because of the audience’s experience with audio-system feedback. After all, unity loop gain is the basis for squeal when sound systems suffer from excessive feedback, and that oscillation certainly involves a lot of voltage “transiting.”

One problem with such interpretations is that the hyperbola is valid only for constant open-loop gain. More important, they ignore that the relationship represented by the hyperbola is an equilibrium relationship: the hyperbola doesn’t apply to dynamic effects like oscillation. (Well, the equation on which the hyperbola is based actually can be used to characterize steady-state oscillation. But that would require complex values: the geometric representation would require four dimensions instead of the hyperbola’s two.)

So attempts like Mr. Stokes’ to demystify the feedback equation itself are all well and good. But it’s also important to recognize that the equation’s very simplicity can be misleading, even for someone who “was given training in the mathematics of what are called conic sections.”

Now let’s complete our study of the system’s behavior with the other view of closed-loop gain.

Instead of slightly increasing as the temperature-input view’s large-signal gain did, the forcing-input view’s actually continues to decline right up to the tipping point. But the overall effect is the same: the small-signal gain rises dramatically as the tipping point is approached, whereas the large-signal gain does not.

In short, we’ve worked through a counterexample to the proposition that high ECS values are inconsistent with a system whose feedback responds to emission temperature. In doing so we’ve detected no contradictions of feedback mathematics. But by juxtaposing small- and large-signal versions we’ve seen how important it is to distinguish between them consistently.

6. “Near-Invariant”

Before we conclude, we’ll use one of Lord Monckton’s reactions to such counterexamples to illustrate why it’s important to “work it out” and not just “scope it out.”

Ordinarily Lord Monckton’s reaction to such counterexamples is merely to express his disbelief that the function could be so nonlinear. Or he makes the physical argument that the quasi-exponential response of evaporation to temperature somehow conspires with the quasi-logarithmic response of forcing to concentration to make the entire sum of water-vapor, albedo, lapse-rate, cloud, and other feedbacks linear. Again, though, such arguments are irrelevant. The point isn’t whether we think the function is nearly linear. It’s whether that’s what feedback math requires: it’s whether Lord Monckton has as he claimed achieved an actual proof rather than a mere conjecture.

But this time he argued as follows that it’s “official climatology,” not feedback theory, that imposes the near-linearity requirement. (Presumably he meant “near-invariant” instead of “near-linear” in writing that “official climatology’s view” is “that the climate-sensitivity parameter . . . is ‘a typically near-linear parameter’.”)

“[The counterexample is] spectacularly contrary not only to all that we know of feedbacks in the climate but also to official climatology’s view that the climate-sensitivity parameter, which embodies the entire action of feedback on temperature, is ‘a typically near-linear parameter’.”

“It is only if one assumes that there is no feedback response to emission temperature that climatology’s system-gain factor gives a near-linear feedback response. . . .

“It is only when one realizes that feedbacks in fact respond to the entire reference temperature and that, therefore, even in the absence of the naturally-occurring greenhouse gases the 255 K emission temperature itself induced a feedback that it becomes possible to realize that, though official climatology thinks it is treating feedback response as approximately linear it is in fact treating it – inadvertently – as so wildly nonlinear as to give rise to a readily-demonstrable contradiction whenever one assumes that any point on its interval of equilibrium sensitivities is correct.”

(As an aside we note that Lord Monckton left unspecified the standard by which a system like that of Fig. 1 can be said to be “wildly nonlinear”. Nor did he “readily [demonstrate]” a contradiction that would arise even from a sytem like that of Fig. 8, which we so designed as to provide an imminent tipping point.)

For the sake of convenience we’ll use Lord Monckton’s notation to unpack a couple of those assertions.

First, although he often criticizes “official climatology” for focusing on perturbations in its ECS calculations, he apparently chose in this context not to interpret climatology’s use of “near-invariant” or “near-linear” as limited to the ECS calculation’s perturbation range; he interprets the near-linearity as applying to the function more generally or at least to its entire portion above the emission temperature.

Second, the projection line in Fig. 1 above illustrates what he seems to mean by “It is only if one assumes that there is no feedback response to emission temperature that climatology’s system-gain factor gives a near-linear feedback response.” If you’re considering the stimulus to be only the portion of that exceeds the emission temperature, then the response could be the projection-line portion to the right of the emission temperature. Such a response would have only a single, relatively high slope. If the stimulus is taken as the entire

value, though, then the response has a lower-slope portion as well, and that slope change contradicts what he says is “official climatology’s view” that the response is nearly linear.

That his interpretation of “official climatology’s view” thus results in a contradiction isn’t a very compelling argument by itself. His interpretation is almost certainly a misreading of the literature. And, if you choose a contradictory interpretation over the more-probable non-contradictory one, you’re bound to find, well, a contradiction.

But in a further comment he seems to say that climate-model results confirm his interpretation of “official climatology’s view”:

“[W]e are not doing calculations in vacuo. The head posting demonstrates that official climatology regards—and treats—the climate-sensitivity parameter as near-invariant: calculations done on the basis of its error show that the system-gain factor in 1850 was 3.25 and the mean system-gain factor in response to doubled CO2 compared with today, as imagined by the CMIP5 ensemble (Andrews+ 2012), is 3.2. Looks pretty darn near-linear to me.”

Climatology must have intended a nearly linear function, that is, if its slope exhibits so little variation in that interval. And, if climatology intended it to be nearly linear, then feedback would reach zero at the emission temperature: climatology’s position is that there’s no feedback to the emission temperature.

Before we show that this standard for “pretty darn near-linear” is too loose to rule out every counterexample, let’s recognize that drawing an inference from differences so dependent on ensemble selection is a parlous undertaking. For instance, a polynomial fit to the combination of those “system-gain factors” with the and

values Lord Monckton attributed to “official climatology” in the same thread would imply a cubic

function that intersects

at

. That’s not very linear. Also, climatology could still be right about ECS even if it’s wrong about lower-temperature behavior.

But let’s nonetheless assume “official climatology’s view” to be that the closed-loop gain won’t vary by more than 3.25 – 3.20 = 0.05. As the plot below shows, this assumption still doesn’t support the inference that “official climatology” has “made the grave error of not realizing that emission temperature (= 255 K) itself induces a substantial feedback.”

For the interval over which Lord Monckton reports the variation in “system-gain factor” the plot displays the temperature-input view’s closed-loop-gain functions not only from the example system but also from that of Fig. 1. As to the large-signal versions, the different feedback functions’ results are virtually indistinguishable, and they vary only negligibly over the interval.

As to the small-signal versions, it’s true that the variation caused by the example, tipping-point-causing feedback function greatly exceeds the arbitrary “near-linear” limit, 0.05. But that limit, which made the “official climatology” closed-loop function look “pretty darn near-linear” to Lord Monckton, is actually 9 times the gain variation 0.0053 caused by Fig. 1’s feedback function—which, again, responds to the emission temperature.

Although a closed-loop function may look “pretty darn near-linear” when we just scope it out, that is, it can look quite a bit different when we actually work it out.

7. Conclusion

The equilibrium scalar feedback equation is the most rudimentary of feedback topics; the algebra is trivial. Yet, as we saw in connection with Fig. 12’s hyperbola, its interpretation isn’t straightforward even when the system is linear. And for nonlinear systems it provides a good occasion to recall that simple rules can result in complex behaviors. So any feedback question calls for following that professor’s advice: Don’t just scope it out; work it out.

Joe: I thought that Lord Monckton might have elucidated the emission temperature without feedbacks (because “the sun is simply shining”) better if he had taken us through from zero CO2 through growth to the 280ppm by 1850. Then all the increases would be “bins” of perturbation in the system. Is this a sensible thing to try mathematically? Or was this ostensibly done in his work with one leap in CO2 to 280ppm? i.e: what should the temperature be at 50, 100,150…..ppm CO2 by “first principles”.

You can have all the “first pricipals” or “basic physics” you like but unless and until you can correctly measure ( and THEN model ) evaporation of wind driven sea water; convection, advection, cloud formation ( at all levels ) and precipitation, all the rest becomes useless.

We understand fairly well the additional radiative “forcing” caused by an increase in CO2 at current levels, but until you have an equally good understanding of the water cycle FORGET IT, you do not have a means to even model what has already happened, let alone extrapolation 100y hence.

It is all non-scientific bunkum.

Even Christina Figeras openly admitted, CO2 does not matter, it’s all about wealth redistribution and destroying western economies.

Oh I’m with you on that.

I’m afraid I can’t give you a good answer.

I don’t think we can fault Lord Monckton too much for not mapping to E(R) all the CO2 concentrations between 0 and 280 ppm; that would take us into the non-logarithmic regime. For the particular concentration of 0 ppm, though, he tells us what “official climatology” supposedly says the (E, R) value is: it’s the intersection of Fig. 1’s dashed projection line with E = R.

Since he says that value is wrong, he should tell us what value he thinks is right, or at least provide a range, together with a compelling reason for that value or range.

My problem is that I haven’t taken note of whether he’s done that or not, because in my view he hasn’t made a good argument for believing that the “official climatology” value is what he says it is. So, whatever he thinks it should be, he doesn’t have a good basis for contending its value isn’t what he thinks it should be.

“For the particular concentration of 0 ppm, though, he tells us what “official climatology” supposedly says the (E, R) value is: it’s the intersection of Fig. 1’s dashed projection line with E = R.”

Yes, but he also says that both must be linear and pass through 0 at T=0. That is really the origin of his fixed low sensitivity. If they intersect at the emission temperature, as you sketch, you actually get a very high sensitivity on his arithmetic; still true with your more curved black line (Fig 1). But I think a lot more care needs to be taken with properly defining what R and E(R) are. Lord M didn’t do that.

SIMPLE SUMMARY

In order to test the hypothesis presented by Lord Monckton that the climate sensitivity to must be small, Joe first takes standard feedback terminology and shows how it relates to Lord Monckton’s terminology (which is obscure to the extent my first inclination in reading the paper was to rewrite it using more standard terminology).

Joe then adapts this for feedback and gain which vary and introduces a hypothetical feedback function which would create a “tipping point” (infinite loop gain) at around a doubling of CO2. This is just an arbitrary equation chosen by Joe to “test” the feedbacks and see/show that high gain is possible.

Joe then shows that there is no limit to the gain which increase to infinity at the “tipping point”. This is all very reasonable, and Joe says this contradicts what Lord Monckton says. I see nothing wrong with the logic from Joe and this behaviour is quite to be expected and what I couldn’t understand about Lord Monckton’s original post.

The key issue, which seems to be at point, is whether “gain” should be the average slope from a “zero” temperature to the current temperature or whether it should be the change that occurs for a small variation.

To use a simple analogy, should the slope of a hill be the slope in the immediate vicinity or taken to be the change in height divided by distance from the start of the road.

I would agree with Joe that the slope (gain) should be the slope at the current temperature and not the slope of the average slope from a “zero” temperature. I would only say, that because Lord Monckton’s original paper was so difficult to interpret, that I cannot say Joe is right and Lord Monckton wrong, only that I cannot see anything wrong with Joe’s argument.

Roy W. Spencer makes a good point about ” But the Planck effect (nonlinearly increasing IR loss as temperature rises, from the Stefan-Boltzmann relationship) always dominates as the “feedback” that dominates the net feedback parameter. Unfortunately, some idiot in the early days of climate change science decided this term would not be called a “feedback”” … the question here is what constitutes the “system”. This is a consistent problem in climate which seems to pick and choose system boundaries in an arbitrary way as it when it choses and often uses two boundaries at the same time (particularly in thermodynamics).

However, this whole debate really does smack of arguing how many angels fit on the head of a pin. The fact is that the IPCC statement of feedbacks is the biggest load of hogwash with zero credibility which would be cringeworthy if handed in by a first year student. There is no substantive evidence I have seen except that based on Ice-cores by which any reasonable person could give any figure for the feedback at present. So Lord Monckton is right that the IPCC is wrong.

The reality is that whilst the IPCC is right that there are positive feedbacks present in the climate for temperatures significantly lower than the present temperature, USING THE SAME ICE CORE DATA, any reasonable person who understood signals, would conclude that there are strong negative feedbacks for temperatures significantly warmer than the present temperatures. To put it simply …. whilst positive feedbacks can explain the rapid rise in temperature at the end of the ice-age, if they were still present, the temperature would continue rapidly rising. The fact that the interglacial is not only stable nut consistent in temperature is clear evidence of strong negative feedbacks at or slightly above the present temperature.

And if Willis Eschenbach would get in touch with me, we might start making progress in proving the existence of those negative feedbacks in the present climate.

Just for background, I’ll mention that I, too, believe that ECS is low if it exists at all. Also, I’m inclined to think–but I claim no particular expertise–that feedback is so nonlinear as to impose almost a hard limit at some value several degrees above the current one. I find the data in Willis Eschenbach’s thermostat posts compelling in this regard, but I’ll be the first to admit that on that subject as opposed to feedback math my opinion is about as good as that of the guy on the next barstool.

As to what Lord Monckton really means, that’s always a question; in my view his positions are preposterously protean. But he seems to use what it has become fashionable to call a motte-and-bailey argument. The bailey is set forth in that video: he’s come up with an absolute proof that should compel the assent of people who had heretofore thought ECS is high. The motte is a combination of physical and literature arguments of indifferent persuasiveness that in any event don’t rise above the level of what he classifies in the video as conjectures.

If you have the time and a high enough threshold of pain, you may want to consider viewing that video.

OK, back from looking at the video. Which I thought was rather good.

However, now I realise there is an issue. The issue is not whether to use the change in temperature of absolute temperature, but what values to use to calibrate the equation. I’m not sure where Monckton gets the 2.25K value for final temperature rise … unless it’s the IPCC central estimate … which was obtained using the IPCC curve for gain based on the method of calculating gain which Monckton is rejecting … however….ignoring that…

There is a reasonable question as to whether gain equation should be calibrated with the differential gain (2.25/1.05) or the total gain (T0 + 2.25 / T0 + 1.05). In theory they will give the same result … but if the total gain is used, then you need to add an extra offset term (which Monckton did not) and use two points to calibrate it. The first is the output with no change (255 in 255 out -> offset = 255), the second with the new temperature in (255+1.04) – offset being amplified to (255 + 2.25) – offset.

Another question is whether the feedbacks only operate on the differential change in temperature or whether e.g. on the temperature from a “neutral” (black body) earth or indeed, some other “base” temperature. However, that consideration is only material if you know a potential base “no gain” temperature and have a “DC” or long-term average temperature.

That however, leads onto the much more powerful criticism of the IPCC approach is that almost all gains are frequency dependent. And it really beggars belief that we get this crap about feedbacks without any discussion about frequency responses.

Because even if the IPCC could measure the short-period gain (high frequency) this tells us NOTHING about the long term gain which could be a lot higher or a lot lower than the short-term gain. That is because feedback mechanisms that take several decades or even centuries to respond, will have virtually no effect on temperature changes occurring within months. (As I’m sure you know – but just making the point readable to others)

Just as a final point … for fun work out the feedback level that would be required for a change in CO2 (180 to 270?) to cause the 8C warming. From memory its over 10. Any person who understands feedbacks will immediately spot that is a huge problem with the “CO2 control knob of climate” claim.

System gain can be calculated from the large signal response of a step function and measuring how long it takes for the system to dampen back to equilibrium. For example if a volcano exploded or a meteor hit the earth. The earth looks like a huge capacitor to the system (using EE terms). There are two ways to then cause the output temperature to rise (or fall), one is the feedback term for the system and the other is to change the input power of the system. We will see one of these over the solar minimum we are going through now). Since we have never been in an oscillation (even after glaciation, volcano, and asteroid hits the overall system gain has to be low (see capacitor analogy above). Remember an permanent oscillation that can’t be broken by its feedback is what defines an unstable system.

Large scale signal responses are step functions. These would be events such as an Astroid impact or volcano. Everything else is small signal (glaciation cycles for example). If you have a step function that dampens out over time, you must by definition have a critically or over damped system, otherwise you oscillate (from which you never recover). You can estimate the sensitivity (gain of the system and phase margin) from the time it takes to ring out a perterbation.

I agree that actually measuring the small-signal values would be problematic, but everyone authoritative I’ve heard—and I hasten to add I know nothing about the models myself—says that Lord Monckton is wrong about how “official climatology” partisans come up with their small-signal, “perturbation” metrics. They instead get them from the models, which means they get them from their physics and fudge factors, not measurements. That’s the IPCC’s problem, they say: their models’ fudge factors, not dodgy measurements.

Separate issue: My apologies but I just realized I may have given you a bum steer. If I recall correctly, the calculation in that first video is not the way he now says it’s done. (And you may have noticed that its block diagrams are not consistent with each other.) For his current story, go to the numbers in the “end of the global warming scam in a single slide” at the end of his post at https://wattsupwiththat.com/2018/08/15/climatologys-startling-error-of-physics-answers-to-comments/ , which boils down the calculation he made in a different, later video, the one at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kcxcZ8LEm2A.

If you still have the stomach for this and enjoy a challenge, try to figure out what his error is in subtracting equations at 21:00 into that later video. If he admits the difference is a “true equation,” why doesn’t that mean that the other answer is wrong?

Joe, thanks to your patient analysis, yes now I look at the slide, I can see what Christopher is getting at and to be frank, it might make sense to a mathematician without any idea about the climate, but it makes no real physical sense. In short, it is insisting that the system has to be linear down to 0K which means that CO2 has to have an effect when there less than nothing there. That is CO2 has to have an effect below earth’s blackbody temperature. By definition there is no atmospheric effect for the blackbody temperature & no atmosphere, so Monckton is trying to insist feedbacks operate when CO2 levels fall BELOW ZERO which supposedly means they are actively cooling when there is less than no CO2 there. That’s like picking another arbitrary “zero” of -100K (BELOW ABSOLUTE ZERO) and saying the feedback effect has to operate down to that level. Yes, mathematicians and IPCC “scientists” may be able to make that work in their own minds, but in the real world it doesn’t.

I think the argument could be: if the system of atmospheric heating effects is linear (so taking 255K, (the blackbody temperature of the earth as a base), then the feedbacks on part of the CO2 warming (from 1850) should apply to the whole CO2 effect. But before we start, the insistence the system is linear is hard to sustain as the effect of CO2 is non-linear and IR cooling is non-linear.

But an assumption of linearity might yield a/some limit(s) on the system, as I point out below (in my previous comment), but I don’t much see the point as the inevitable conclusion would be that the system isn’t linear.

The real criticisms that can be aimed at the IPCC are twofold:

1. The IPCC calculates gain without taking any account of natural variation … which as we know its the same size or greater than recent changes allows the possibility that CO2 has no effect at all. You’ve got to be pretty insane, dishonest or ignorance to claim any certainty for climate sensitivity like the IPCC.

2. The IPCC ignores the necessary change from positive to negative feedbacks which are necessary to bring the climate system to stability at the inter-glacial temperature. So, they are happy to cite positive feedbacks – but they ignore the necessary feedbacks that MUST OCCUR and are inherent in the same analysis. In other words, they cherry pick the “helpful” positive feedbacks and ignore the negative ones that totally ridicule their “science”.

Mr. Haseler:

Pardon the delay; I saw your comment previously but forgot to respond.

I agree with your criticism of the slide that “it is insisting that the system has to be linear down to 0K.” But I don’t think that fact necessarily implies “that CO2 has to have an effect when there less than nothing there.”

True, the major temperature-independent forcing (i.e., the head note’s x) that we usually talk about is carbon-dioxide concentration (although ocean outgassing gives that a temperature-dependent portion, too). Theoretically, though, forcing could include even conceptual things like turning on the sun.

Forced by Lord Monckton’s theory to treat forcing as an entire-quantity input rather than a perturbation, we could start at absolute zero with, say, no sun or stars and then observe the results of slowly increasing those heavenly bodies’ output power to current levels. Or we could start with the sun and stars in place but with unity albedo for the earth so that it again begins at absolute zero. We’d observe the results of slowly decreasing albedo to current levels.

In both cases we’d also slowly increase noncondensable-greenhouse-gas concentration. The feedback would then be the temperature-dependent forcing caused throughout the temperature range by things like (the temperature-dependent portion of) albedo and water-vapor concentration and the consequent cloud and lapse-rate effects.

This may raise awkward questions about the order in which the temperature-independent forcings would be applied, but it’s theoretically consistent in principle. So, viewed as charitably as possible, Lord Monckton’s theory doesn’t require negative carbon-dioxide concentration.

However, the fundamental problem you identified remains: nothing in feedback theory requires the resultant equilibrium temperature E to be a nearly linear function of the value R it would have had without feedback. In view of the phase-change temperatures of water, whose vapor is what “official climatology” contends is responsible at current temperatures for most positive feedback, there is little reason to expect linear consequences throughout the entire temperature range from absolute zero to current levels.

Back again after looking at Monckton’s original (https://wattsupwiththat.com/2018/07/30/climatologys-startling-error-an-update/).

He doesn’t quite make the same point you suggest, instead he hints at an issue, which you have shown to be false. But I don’t think that is the key to his argument and I think I can make an argument based on Monckton’s paper which is coherent.

The black body temperature of the earth is about 255K meaning there is about 32C of “atmospheric effect”warming the temperature making the average surface temperature is 287. (I’ll use this temperature not 288 for simplicity)

I don’t have figures to hand, but let us support that CO2 is known to causes 16C of warming. If we assume a linear feedback, we can then use this figure to work out the total amplification of this warming and therefore feedbacks. The amplification is therefore 32/16 or 2x, meaning the positive feedback is 0.5. If however, CO2 is a more powerful IR active gas (IRAG), causing 24C of warming then the amplification is 32/24 = 1.333 so that the necessary feedback is 0.25. If CO2 is a much less powerful IRAG and gave 8C of warming before feedbacks, then the amplification is 4x and the necessary feedback is 0.75.

Now let us add in another cause of warming (clouds) which is unaffected by CO2 and suggest it causes 16C of warming. If CO2 causes an additional 16C of warming, then the amplification factor is the increased temperature not attributed to cloud (32 – 16) divided by the CO2 warming so 16/16 (feedback =0). If however CO2 is a much more potent IRAG and causes 24C of warming, the amplification is 16/24 = 2/3 and the feedback is -0.5, if CO2 is a much less potent IRAG and causes only 8C of warming, the amplification is 16/2 = 2 and feedback is +0.5.

The important thing here, is that the higher values of amplification can only be justified if you don’t have anything like clouds that independently cause warming of the atmosphere above the black body temperature AND the effect of CO2 is small.

So, for example to get the 7C warming which I’ve seen as a top estimate for CO2, the amount of warming caused by CO2 without feedbacks in the atmosphere has to be 32/7 = 4.6C . That would require the 1C per doubling of CO2 rule has to stop at 15ppm. In other words, up to 15ppm there would be no warming from CO2, and thereafter each doubling afterwards would cause 1C rise. It also means that clouds would have to have no effect on the planetary temperature (which is a little hard to support if anyone goes out on a cloudless night to see the frost). It seems unlikely these are correct which is what is needed for a linear feedback system for the climate and a rise of 7C for a doubling of CO2.

CONCLUSION

Monckton’s original article made a claim that the climate cult (my words) misinterpreted feedbacks and amplification. I don’t think that can be substantiated given the way they calculate their feedback figures. However, I do think an argument can be made that the IPCC are using a linear model of feedbacks and therefore they MUST work with the total increase in temperature over the blackbody temperature which they do not.

When we use the total temperature over blackbody, it seems the figures aren’t credible (Monckton is right the IPCC have made a mistake). However, the conclusion that should be drawn, is not that the amplification value is wrong, but instead that the system cannot be linear with a constant amplification as implied by the IPCC.

Once you accept that feedbacks are not linear and will change with temperature, then we can start discussing how they reduce as the temperature rises to bring the ice-age warming under control.

I have a question for those who believe the water vapor feedback mechanism, as postulated by Soden & Held in their 2006 paper, does in fact exist.

Do CO2 and methane have a unique ability to activate the postulated water vapor feedback mechanism, if these substances are being continuously added to the atmosphere and their concentration is steadily increasing?

Stating the same question another way, could other kinds of processes not associated with the continuous addition of CO2 and methane to the atmosphere cause a water vapor feedback mechanism to become activated?

I wrote the post because I know something about feedback, not because I’m a climate expert. So take this with a grain of salt.

But I think the answer is that anything that affects the surface temperature will supposedly cause water-vapor feedback as a result.

As the temperatures get much lower than current ones, the feedback per degree of temperature change presumably diminishes, as the feedback-ratio plots suggest.

“But I think the answer is that anything that affects the surface temperature will supposedly cause water-vapor feedback as a result.”

Indeed so.

Joe Born: “But I think the answer is that anything that affects the surface temperature will supposedly cause water-vapor feedback as a result.”

Does this not imply that any process which can raise the surface temperature 1C to 1.5C over some period of time will be amplified by the water vapor feedback mechanism into a 3C rise, plus or minus?

“will be amplified by the water vapor feedback mechanism”

Why do you assume amplification? If the increased water-vapor causes a higher albedo or if it absorbs some of the infrared coming from the sun and re-emits it toward space it could decrease the temperature rise. I.e. it could be a net negative feedback.

What Mr. Gorman said.

My own guess is that through a wide variety of highly nonlinear effect including clouds, more precipitation efficiency, and other things the feedback if no negative at this point turns highly negative as a greater portion of the world gets warm.

But I don’t know.

Tim Gorman:

Joe Born:

Let’s get back to the question I originally asked.

Are CO2 and methane uniquely capable of initiating Soden & Held’s postulated water vapor feedback mechanism, as opposed to other processes which might also initiate this postulated water vapor feedback mechanism?

The emphasis here is on ‘postulated.’

Joe Born’s response was that if Soden & Held’s theoretical water vapor feedback mechanism does in fact exist, then any rise in surface temperature regardless of its source can initiate the postulated mechanism.

If the feedback mechanism does in fact exist, but sources of the rise in surface temperature other than CO2 and methane can in fact cause it to be initiated, then the most tortuous and self-evident questions begin to arise concerning the validity of the “GHG’s are death to the earth” climate science theme.

“If the feedback mechanism does in fact exist, but sources of the rise in surface temperature other than CO2 and methane can in fact cause it to be initiated”

What rise in surface temperature do you believe is happening? Remember, a rise in the AVERAGE temperature can be caused by an increase in maximum temperatures, by an increase in the minimum temperatures, or a combination of the two.

Exactly what feedback mechanism would cause the minimum temperatures to rise while maximum temperatures do not? Exactly what feedback mechanism would cause maximum temperatures to rise while minimum temperatures do not?

Let me reiterate what I said earlier. Conditions today are not that dissimilar to conditions the Earth has seen in the past. If we are seeing a net positive feedback today then it should have also existed in the past and the Earth should have turned into a molten rock orbiting the sun long ago. This leads to the conclusion that the thermodynamic system known as the Earth has a net negative feedback mechanism, probably with a very slow response time. That slow response time allows for natural variability to occur but over the long haul we simply won’t see any “run away” condition occur. If the climate models don’t match this conclusion then just how accurate can they be?

Beta Blocker: https://wattsupwiththat.com/2019/07/16/remystifying-feedback/#comment-2747785

Tim Gorman: https://wattsupwiththat.com/2019/07/16/remystifying-feedback/#comment-2747965

The state of science is such that it is currently impossible to directly observe a feedback process operating in real time inside the earth’s atmosphere in the same way we would observe an electronic circuit operating on a test bed in a laboratory.

The presence and characteristics of such feedback processes, if they actually exist, must be inferred from other kinds of observations. Everyone is free to pick a set of observations, a theory to explain the observations, and a mathematical representation of the theory to describe its operational characteristics.

Soden & Held have theirs, Lord Monckton has his, Joe Born has his, and you Tim Gorman have yours. Mirror, mirror, on the wall, who has the fairest feedback theory of all?

This was my original question concerning the Soden & Held version of temperature feedback theory:

Since 1880, the earth’s global mean temperature has risen approximately 1C, more or less, depending upon which analysis you choose to believe — HadCRUT4, Best, whatever.

If Soden & Held’s water vapor feedback mechanism does in fact exist, but sources of the rise in surface temperature other than CO2 and methane can in fact cause it to be initiated, then what are the most obvious and tortuous questions which follow?

Suppose for purposes of argument that 0.3C of that 1C rise is assigned to natural variation, with the bulk of that allocation assigned to the time period of from 1880 to 1945.

These implications follow from this initial assumption:

— If the Soden & Held amplification factor is 2, then does it not follow that 0.6C of the 1C rise between 1880 and 2018 might possibly have been a consequence of natural variation?

— If the Soden & Held amplification factor is 3, then does it not follow that 0.9C of the 1C rise between 1880 and 2018 might possibly have been a consequence of natural variation?

If, for purposes of argument, we choose to work within the Soden & Held feedback model and to accept its basic tenets, then we have to ask the question: Does the continuous addition of CO2 and methane to the atmosphere have a unique ability to drive their postulated water vapor feedback mechanism, as opposed to other kinds of processes which might produce an equivalent result?

I completely understand what you’re driving at, it’s a point I’ve made many times in many different internet “discussions” of “climate science.” The postulated “positive feedback loop” from water vapor that will SUPPOSEDLY turn the (purely hypothetical) MINOR supposed “CO2 warming effect” into panic-worthy “runaway global warming” is and has always been obvious bullshit.

If it worked as they say, ANY increase in temperature would kick off the same “runaway greenhouse effect,” since the initial temperature rise causes more evaporation, thereby putting more water vapor in the air, thereby (since water vapor is a greenhouse gas) increasing the temperature some more, causing MORE evaporation and putting MORe water vapor in the air, and so on, and so on, and so on. In other words, such a “water vapor feedback” would just as well feed upon itself – who needs CO2?!

All one needs to do is take even the most cursory glance at the Earth’s paleoclimate record, and they will instantly be able to see what utter nonsense the notion of such a water vapor “positive feedback loop” is.

7,000 ppm CO2 couldn’t induce such a “runaway greenhouse effect,” and 4,000 ppm couldn’t stop a “hot house” Earth from plunging into an “ice house” Earth (which according to what today is laughingly called “climate science” should be IMPOSSIBLE), so 400ppm, 560ppm, 800ppm or any other level we’re supposed to be panicked about isn’t going to do it either.

Bottom line is that there is NO empirical evidence that CO2 drives the Earth’s temperature – NONE. Despite the best efforts of the climate pseudo-scientists to “find” such evidence. The notion that atmospheric CO2 levels drive the Earth’s temperature has always been and remains nothing more than a poorly based ASSUMPTION.

Several commenters have asked for an abstract. I’ll provide two.

For the benefit of those whose attention spans are short, the first consists of only a single sentence:

“Although the equilibrium scalar feedback equation is simple, we demonstrate that it’s been subject to misinterpretation and can yield complicated behavior.”

The longer alternative abstract requires that the reader sustain his attention for three full paragraphs:

“Christopher Monckton agrees with heavy hitters like Lindzen & Choi that ECS is low. But Lord Monckton says of such researchers that they ‘can’t absolutely prove that they’re right.’ In contrast, ‘we think that what we’ve done here is to absolutely prove that we are right.’

“His absolute proof’s premise? A fact that he says is ‘well established in control theory but has, as far as we can discover, hitherto entirely escaped the attention of climatology’. Specifically, it’s that ‘such feedbacks as may subsist in a dynamical system at any given moment must perforce respond to the entire reference signal then obtaining, and not merely to some arbitrarily-selected fraction thereof.’ He then contends that if this alleged controls-theory tenet ‘is conceded, as it must be, then it follows that equilibrium sensitivity to doubled CO2 must be low.’”

“We demonstrate that, on the contrary, a low ECS value doesn’t necessarily follow from that tenet. We calculate and display the behavior of a dynamical system that not only exhibits a high ECS value but also a tipping point even though the feedbacks that ‘subsist’ in it ‘at any given moment . . . respond to the entire reference signal then obtaining.’”

Hehe, well, since when was anything at all in climate models ever proven, let alone ‘absolutely’ proven?

If it is just Lord M.’s style to overstate his case a bit, that doesn’t “prove” him wrong!

Let’s say that we were to look at some of the different ideas for climate models as a *choice* of what is best to think about, at least as an idealization, or as a beginning? Say then you think that some of the models are significantly flawed in some way that has ‘slipped by’ or gone unrecognized. At that point wouldn’t you want to pick something else, with at least *that* flaw removed?

What I’m saying here is that no matter how definite people might like to be in their ideas, even the idea of ‘proof’ can be a relative thing, or have implications that depend on context! Say, if you think you’ve now chosen a better option for climate models, haven’t you then “proved” out a better choice in some sense?

“Lord Monckton says of such researchers that they ‘can’t absolutely prove that they’re right.’ In contrast, ‘we think that what we’ve done here is to absolutely prove that we are right.’”

What isn’t often noticed here is that that does indeed “prove” that everyone else is wrong, including local heroes like Lindzen and Lewis. People like to say that he is reinforcing the lo ECS values that they claimed. But no, he’s saying that they, like “official climate science” are getting it all wrong. making the same grave errors.

Thanks for the additional clarifications and the abstracts.

And, tipping points can go both ways?

There are undoubtedly “tipping points” as we move between glacial and inter-glacial periods. There are also undoubtedly “hard stops” which are thresholds at which those positive feedbacks turn to negative feedbacks at the inter-glacial temperature.

So, yes, tipping points can go both ways -and the next time humans will experience one is when a small initial cooling turns into headlong cooling of several degrees. In contrast, by raising temperature we are stabilising the climate.

Thanks, Mike, and I agree based on our empirical knowledge of Earth’s past climate history. I was just wondering if Joe Born’s work in this article allows for such. I assume so by reading some of the charts “right to left” rather than “left to right”.

But, I do lean in Christopher’s (et. al.) direction as his fractional changes match the necessary fractional changes in the models (the average, at least) that are needed to bring their past output to agreement with measured/proxied temperature data.

(And, thanks to Joe Born, again, for all of his follow-up comments and abstracts.)

The head post really doesn’t have much to do with the type of tipping points Mr. Haseler mentions, which is why I should perhaps have made clear that I was using the phrase in a narrow if not idiosyncratic way.

Nonlinear-feedback systems more complicated than I dealt with above can execute limit cycles, seek strange attractors, and exhibit many other kinds of unanticipated behavior the head post doesn’t consider.

Again, it’s complicated, and the head post merely scratches the surface.

I’m not sure what you mean by “go both ways.” In the example system, the output in response to a forcing increase beyond the tipping point only increases without limit. But I used only very simple functions. For others, I’d have to “work it out.”

An interesting technique called “Lyapunov’s direct method” is sometimes used in this connection, but I must confess that when I studied it in depth computer power wasn’t great enough to do much interesting with it. And I’ve only touched on it since. So I’m afraid I’m just giving you a buzz word.

On the other hand, the head post does give examples of unstable equilibrium in both linear and nonlinear cases. And, as it explained, the output could head off to infinity in either direction, or it could end up seeking a stable equilibrium state. Unstable-equilibrium states aren’t what I used tipping point to mean, but others may use it differently.

In other words, like many implications of the simple scalar equilibrium equation, it’s complicated.

Thanks for your response, Joe. I’m just not certain that electronic circuitry theory works for me regarding climate changes, even Christopher’s, although I have to say that his effort does get what I’m looking for, and that is, bringing model outs closer to actual temperature data (such as it is). I’m not settled on that uncertainty, just not fully convinced.

The “goes both ways” referred to the prospect of the described “circuit” allowing for a temperature tipping point that has temps increasing or decreasing. Or, does that require separate “circuits” for an increase or decrease. Of course, the “circuits” are just mathematical expressions and math can describe most anything given enough terms so maybe that answers my uncertainty. Just think math. And more terms.

Interesting discussion.

JRF, the Simple-Minded Biologist.

As to your comment about circuit theory, I’ll just mention that nothing about the head post’s equilibrium scalar feedback equation is specific to electronic circuits. (But one is entitled to question whether feedback requires that the combination of output-dependent and -independent parts of

is specific to electronic circuits. (But one is entitled to question whether feedback requires that the combination of output-dependent and -independent parts of  ‘s argument would necessarily have to be additive, as they are designed to be in most circuits and control systems.)

‘s argument would necessarily have to be additive, as they are designed to be in most circuits and control systems.)

Your “goes both ways” question actually deals with states of unstable equilibrium, although it’s quite understandable that they would get conflated with what I meant by tipping point, which is the input beyond which there’s no equilibrium.

To answer your “goes both ways” question, the “both ways” apply to the same system.

To see this, place the simpler, linear system in the (unstable) equilibrium state

in the (unstable) equilibrium state  . If you iterate in accordance with

. If you iterate in accordance with  , you confirm that the state is in equilibrium:

, you confirm that the state is in equilibrium:  won’t change.

won’t change.

But now “nudge” the system in two ways:

First, change from 1 to 1.1. Iterating will then increase

from 1 to 1.1. Iterating will then increase  without limit: it will take off to positive infinity.

without limit: it will take off to positive infinity.

Second, reset the system to . Iterating will then decrease

. Iterating will then decrease  without limit: it will take off to negative infinity.

without limit: it will take off to negative infinity.

From the unstable state , that is, the system will take off when nudged to either negative or positive infinity in accordance with the nudge’s direction.

, that is, the system will take off when nudged to either negative or positive infinity in accordance with the nudge’s direction.

As I explained in the head post, nonlinear-system behavior is somewhat different, but the linear-system behavior gives you the basic idea.

Joe Born:

Ah. Helpful!

Thanks. But, still leaning toward CM and will interested to hear about his upcoming presentation.

JRF.

Low solar drives warm ocean phases which reduces cloud cover in the mid latitudes and increases cloud cover in the Arctic. Huge negative feedbacks. The globe would have cooled from 1995 without the AMO acting as a negative feedback to declining solar wind pressure.

Negative feedbacks are not just things that work against another, but one has to cause the other. So saying solar is a “feedback” implies that solar is caused by global temperature. So, if solar is changing cloud, that is not a feedback to the system but a driver.

So your second sentence would be:

“The globe would have cooled from 1995 without the AMO acting as a driver warming the temperature in the face of the cooling effect of declining solar wind pressure.”

As to that statement … all I can say, is that so far there is no evidence of sustained cooling beyond the expected** cooling after the 2016 El Nino

**OK, only sceptics expected it to cool. The idiots in the Climate Cult didn’t.

I did not say solar was a feedback, hello? The warm ocean phases and cloud clover changes are the negative feedbacks to changes in indirect solar forcing, i.e. to the decline in solar plasma pressure/temperature since 1995.

I did not expect sustained cooling after the 2016 El Nino, as I had predicted a continuation of increased El Nino conditions beyond 2016, about 6 years ago on this blog.

**Don’t misquote me.

What Monckton did was show what the elephant looked like if its trunk wasn’t wiggling.

What’s the difference between a marginal tax rate and an average tax rate?

The average rate takes all the prior income and taxes into account.

The marginal tax rate looks at the change in income and the change in taxes.

Assume a relevant range of the U.S. Income tax rates.

Using the average rate hides the bad news if you add some income and your tax rate is 35%. The reality of it is, most accountants would agree the government smacked you for more than a third of the additional income.

I wonder if that’s what happened?

Fixated on anomaly data?

The bottom line, it is all the temperature, or CO2 level, or humidity that has to be processed because that is how nature works in its attempt to seek equilibrium (not that it ever gets there before something has changed).

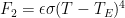

Joe,

Your equations are very similar to ones I have posted on some Monckton threads, except I am sticking with a 1/4 power law. Essentially it is an implicit equation (therefore solved numerically) which says that temperature T is a function of sums of forcings Fi one of which depends on T itself:

T(F) = (F/(εσ))1/4 (2)

Now total forcing F is the sum of F1 + F2 + F3, where F3 depends on T. So

F = F1 + F2 + F3(T(F))

I then derive sensitivity S to doubled CO2 as

S = 3.7 / (4εσT(F)^3 – F3’(T(F)))

So the denominator implies that a tipping point is possible. I then use real world annual observations from Ramanathan & Inamdar (2006) to deduce a plausible value for F3′ of 3.53 and S = 2.12K.

This non-linear theory, which is physically more justifiable than for temperature to feed back directly on itself, gives a significantly higher S (2.1K) than Monckton gets (1.1K), but not too scary. I should like to publish this in a journal, but have lacked the motivation to work hard enough to that end. I could send you a draft if you wished.

I, too, ran the model with 1/4 power, and in a sense it was more interesting. But for the head post I adopted the fractional power 0.37 for two reasons.

The main reason was to match the oft-quoted current-concentration open-loop-gain value of 1/3.2. That’s what I meant above by “a nod toward the real-world difference between the surface temperature and the effective radiation temperature.”

An ancillary reason was that with 1/4 power the instability at absolute zero was more pronounced. That made the gap at absolute zero detectable enough to require that I provide an explanation. As you might have inferred from the above discussion’s caliber, almost no one would have comprehended that explanation. So the power I chose above had the incidental benefit of sparing me a pointless exercise.

As to a paper, I have no academic pretensions. I’m nearing my sell-by date, and even in my working life I was just a workaday lawyer, part of that vast army of gray men who make their living by keeping the gears of commerce oiled.

I bestirred myself in this case only because I’m a citizen, because a significant part of the skeptic community seems to have been taken in by a clearly incorrect understanding of control-systems theory, and because I happen to know that discipline’s rudiments. (And make no mistake; the head post deals with only the most rudimentary of its rudiments.)

That said, I’ll mention that I have reservations about your equation’s use of . Let me emphasize again that I’m no climate scientist. And I may misunderstand what you mean by

. Let me emphasize again that I’m no climate scientist. And I may misunderstand what you mean by  and

and  , so the following observation may be meaningless.

, so the following observation may be meaningless.

But my opinion, as the post said, is that “temperature almost certainly isn’t a single-valued function unless that function’s argument is a vector of forcing components instead of the scalar total thereof we’re assuming here.” In other words, I was alerting readers to the fact that I was averting my eyes from the errors attendant to treating a function of a vector as a function of the scalar total of its components.

For example, suppose that, for some ,

,  and

and  . Then treating the open-loop function as

. Then treating the open-loop function as  would imply that

would imply that  has a one-to-one mapping to distance along a specific but only implicit trajectory through the

has a one-to-one mapping to distance along a specific but only implicit trajectory through the  plane. Now, that’s in essence what the head post did tacitly: if forcing is indeed properly treated as a vector of components whose effects differ, then by treating vector forcing as a scalar sum of its components I was tacitly assuming a trajectory through the forcing-vector space.

plane. Now, that’s in essence what the head post did tacitly: if forcing is indeed properly treated as a vector of components whose effects differ, then by treating vector forcing as a scalar sum of its components I was tacitly assuming a trajectory through the forcing-vector space.

In the case of the head post, I simply avoided this discussion, which would have required more physics that I’m sure of and anyway would have been lost on this audience. But by naming the components explicitly you may instead need to deal with that complication. Or maybe I just don’t understand your approach.

Anyway, those are all the thoughts I have on it. And, again, my purchase on that corner of the problem is somewhat tenuous, so take this comment for what it’s worth.

Joe, thanks for the reply. It is always hard to know whether to post more detail, which can put some people off, or to post less and then be improperly understood.

Anyway, you already guessed that F is for Forcing, in W/m^2. T(F) is the Stefan-Boltzmann 1/4 power equation. The things you couldn’t guess are that F1 is the solar input, F2 is the total CO2 forcing, and F3 is the temperature-dependent effect of water in all its guises, especially albedo from ice and downwelling infrared from water vapour.