Guest post by Nick Stokes,

Every now and then, in climate blogging, one hears a refrain that the traditional min/max daily temperature can’t be used because it “violates Nyquist”. In particular, an engineer, William Ward, writes occasionally of this at WUWT; the latest is here, with an earlier version here. But there is more to it.

Naturally, the more samples you can get, the better. But there is a finite cost to sampling limitation; not a sudden failure because of “violation”. And when the data is being used to compile monthly averages, the notion promoted by William Ward that many samples per hour are needed, that cost is actually very small. Willis Eschenbach, in comments to that Nyquist post, showed that for several USCRN stations, there was little difference to even a daily average whether samples were every hour or every five minutes.

The underlying criticism is of the prevailing method of assessing temperature at locations by a combined average of Tmax and Tmin = (Tmax+Tmin)/2. I’ll call that the min/max method. That of course involves just two samples a day, but it actually isn’t a frequency sampling of the kind envisaged by Nyquist. The sampling isn’t periodic; in fact we don’t know exactly what times the readings correspond to. But more importantly, the samples are determined by value, which gives them a different kind of validity. Climate scientists didn’t invent the idea of summarising the day by the temperature range; it has been done for centuries, aided by the min/max thermometer. It has been the staple of newspaper and television reporting.

So in a way, fussing about regular sample rates of a few per day is theoretical only. The way it was done for centuries of records is not periodic sampling, and for modern technology, much greater sample rates are easily achieved. But there is some interesting theory.

In this post, I’d like to first talk about the notion of aliasing that underlies the Nyquist theory, and show how it could affect a monthly average. This is mainly an interaction of sub-daily periodicity with the diurnal cycle. Then I’ll follow Willis in seeing what the practical effect of limited sampling is for the Redding CA USCRN station. There isn’t much until you get down to just a few samples per day. But then I’d like to follow an idea for improvement, based on a study of that diurnal cycle. It involves the general idea of using anomalies (from the diurnal cycle) and is a good and verifiable demonstration of their utility. It also demonstrates that the “violation of Nyquist” is not irreparable.

Here is a linked table of contents:

- Aliasing and Nyquist

- USCRN Redding and monthly averaging

- Using anomalies to gain accuracy

- Conclusion

Aliasing and Nyquist

Various stroboscopic effects are familiar – this wiki article gives examples. The math comes from this. If you have a sinusoid frequency f Hz (sin(2π)) samples at s Hz, the samples are sin(2πfn/s), n=0,1,2… But this is indistinguishable from sin(2π(fn/s+m*n)) for any integerm (positive or negative), because you can add a multiple of 2π to the argument of sin without changing its value.

But sin(2π(fn/s+m*n)) = sin(2π(f+m*s)n/s) that is, the samples representing the sine also representing a sine to which any multiple of the sampling frequency s has been added, and you can’t distinguish between them. These are the aliases. But if s is small, the aliases all have higher frequency, so you can pick out the lowest frequency as the one you want.

This, though, fails if f>s/2, because then subtracting s from f gives a lower frequency, so you can’t use frequency to pick out the one you want. This is where the term aliasing is more commonly used, and s=2*f is referred to as the Nyquist limit.

I’d like to illuminate this math with a more intuitive example. Suppose you observe a running track, circle circumference 400 m, from a height, through a series of snapshots (samples) 10 sec apart. There is a runner who appears as a dot. He appears to advance 80 m in each frame. So you might assume that he is running at a steady 8 m/s.

But he could also be covering 480m, running a lap+80 between shots. Or 880m, or even covering 320 m the other way. Of course, you’d favour the initial interpretation, as the alternatives would be faster than anyone can run.

But what if you sample every 20 s. Then you’d see him cover 160 m. Or 240 m the other way, which is not quite so implausible. Or sample every 30 s. Then he would seem to progress 240m, but if running the other way, would only cover 160m. If you favour the slower speed, that is the interpretation you’d make. That is the aliasing problem.

The critical case is sampling every 25s. Then every frame seems to take him 200m, or halfway around. It’s 8 m/s, but could be either way. That is the Nyquist frequency (0.04 Hz), relative to the frequency 0.02Hz which goes with as speed of 8 m/s. Sampling at double the frequency.

But there is one other critical frequency – that 0.2 Hz, or sampling every 50s. Then the runner would appear not to move. The same is true for multiples of 50s.

Here is a diagram in which I show some paths consistent with the sampled data, over just one sample interval. The basic 8 m/s is shown in black, the next highest forward speed in green, and the slowest path the other way in red. Starting point is at the triangles, ending at the dots. I have spread the paths for clarity; there is really only one start and end point.

All this speculation about aliasing only matters when you want to make some quantitative statement that depends on what he was doing between samples. You might, for example, want to calculate his long term average location. Now all those sampling regimes will give you the correct answer, track centre, except the last where sampling was at lap frequency.

Now coming back to our temperature problem, the reference to exact periodic processes (sinusoids or lapping) relates to a Fourier decomposition of the temperature series. And the quantitative step is the inferring of a monthly average, which can be regarded as long term relative to the dominant Fourier modes, which are harmonics of diurnal. So that is how aliasing contributes error. It comes when one of those harmonics matches the sample rate.

USCRN Redding and monthly averaging

Willis linked to this NOAA site (still working) as a source of USCRN 5 minute AWS temperature data. Following him, I downloaded data for Redding, California. I took just the years 2010 to present, since the files are large (13Mb per station per year) and I thought the earlier years might have more missing data. Those years were mostly gap-free, except for the last half of 2018, which I generally discarded.

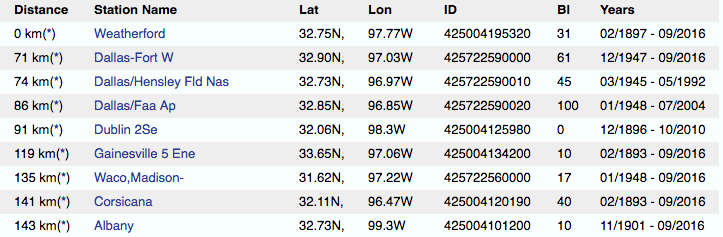

Here is a table for the months of May. The rows are for sampling frequencies of 288, 24, 12, 4, 2, and 1 per day. The first row shows the actual mean temperature averaged 288 times per day over the month. The other rows show the discrepancy for the lower rate of sampling, for each year.

| Per hour | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| 1/12 | 13.611 | 14.143 | 18.099 | 18.59 | 19.195 | 18.076 | 17.734 | 19.18 | 18.676 |

| 1 | -0.012 | 0.007 | -0.02 | -0.002 | -0.021 | -0.014 | -0.007 | 0.002 | 0.005 |

| 2 | -0.004 | 0.013 | -0.05 | -0.024 | -0.032 | -0.013 | -0.037 | 0.011 | -0.035 |

| 6 | -0.111 | -0.03 | -0.195 | -0.225 | -0.161 | -0.279 | -0.141 | -0.183 | -0.146 |

| 12 | 0.762 | 0.794 | 0.749 | 0.772 | 0.842 | 0.758 | 0.811 | 1.022 | 0.983 |

| 24 | -2.637 | -2.704 | -4.39 | -3.652 | -4.588 | -4.376 | -3.982 | -4.296 | -3.718 |

As Willis noted, the discrepancy for sampling every hour is small, suggesting that very high sample rates aren’t needed, even though they are said to “violate Nyquist”. But they get up towards a degree for sampling twice a day, and once a day is quite bad. I’ll show a plot:

The interesting thing to note is that the discrepancies are reasonably constant, year to year. This is true for all months. In the next section I’ll show how to calculate that constant, which comes from the common diurnal pattern.

Using anomalies to gain accuracy

I talk a lot about anomalies in averaging temperature globally. But there is a general principle that it uses. If you have a variable T that you are trying to average, or integrate, you can split it:

T = E + A

where E is some kind of expected value, and A is the difference (or residual, or anomaly). Now if you do the same linear operation on E and A, there is nothing gained. But it may be possible to do something more accurate on E. And A should be smaller, already reducing the error, but more importantly, it should be more homogeneous. So if the operation involves sampling, as averaging does, then getting the sample right is far less critical.

With global temperature average, E is the set of averages over a base period, and the treatment is to simply omit it, and use the anomaly average instead. For this monthly average task, however, E can actually be averaged. The right choice is some estimate of the diurnal cycle. What helps is that it is just one day of numbers (for each month), rather than a month. So it isn’t too bad to get 288 values for that day – ie use high resolution, while using lower resolution for the anomalies A, which are new data for each day.

But it isn’t that important to get E extremely accurate. The idea of subtracting E from T is to remove the daily cycle component that reacts most strongly with the sampling frequency. If you remove only most of it, that is still a big gain. My preference here is to use the first few harmonics of the Fourier series approximation of the daily cycle, worked out at hourly frequency. The range 0-4 day-1 can do it.

The point is that we know exactly what the averages of the harmonics should be. They are zero, except for the constant. And we also know what the sampled value should be. Again, it is zero, except where the frequency is a multiple of the sampling frequency, when it is just the initial value. This is just the Fourier series coefficient of the cos term.

Here is are the corresponding discrepancies of the May averages for different sampling rates, to compare with the table above. The numbers for 2 hour sampling have not changed. The reason is that the error there would have been in the 8th harmonic, and I only resolved the diurnal frequency up to 4.

| Per hour | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| 1/12 | -0.012 | 0.007 | -0.02 | -0.002 | -0.021 | -0.014 | -0.007 | 0.002 | 0.005 |

| 2 | -0.004 | 0.013 | -0.05 | -0.024 | -0.032 | -0.013 | -0.037 | 0.011 | -0.035 |

| 6 | 0.014 | 0.095 | -0.07 | -0.1 | -0.036 | -0.154 | -0.016 | -0.058 | -0.021 |

| 12 | -0.062 | -0.029 | -0.075 | -0.051 | 0.019 | -0.066 | -0.012 | 0.199 | 0.16 |

| 24 | 1.088 | 1.021 | -0.665 | 0.073 | -0.864 | -0.651 | -0.258 | -0.571 | 0.007 |

And here is the comparison graph. It shows the uncorrected discrepancies with triangles, and the diurnally corrected with circles. I haven’t shown the one sample/day, because the scale required makes the other numbers hard to see. But you can see from the table that with only one sample/day, it is still accurate within a degree or so with diurnal correction. I have only shown May results, but other months are similar.

Conclusion

Sparse sampling (eg 2/day) does create aliasing to zero frequency, which does affect accuracy of monthly averaging. You could attribute this to Nyquist, although some would see it as just a poorly resolved integral. But the situation can be repaired without resort to high frequency sampling. The reason is that most of the error arises from trying to sample the repeated diurnal pattern. In this analysis I estimated that just from Fourier series of hourly readings from a set of base years. If you subtract a few harmonics of the diurnal, you get much improved accuracy for sparse sampling of each extra year, at the cost of just hourly sampling of a reference set.

Note that this is true for sampling at prescribed times. Min/max sampling is something else.

Thanks Nick

Can someone ask Mr. Strokes

how there could be more sampling

( or any sampling!)

of those infilled numbers

— those pesky wild guesses

made by government bureaucrats

with science degrees,

required to compile a global average

SURFACE temperature?

And isn’t it puzzling that the surface

average is warming faster than the

weather satellite average … yet

weather satellite data, with far less

infilling, can be verified with weather

balloon data … but no one can verify

the surface data, because there’s no way

to verify wild guess infilling!

Only a fool would perform

detailed statistical analyses

on the questionable quality

surface temperature numbers,

(especially data before World War II),

and completely ignore the

UAH satellite data (simply because

satellite data shows less global warming,

and never mind that they are

consistent with weather balloon

radiosondes).

The greenhouse effect takes place

in the troposphere.

The satellites are in the troposphere.

How could the greenhouse effect

warm Earth’s surface faster than

it is warming the troposphere?

It can’t.

Three methodologies can be used

to make temperature measurements.

The outlier data are the surface

temperature data.

So why are they are the only data used?

This sounds like biased “science” to me !

My climate science blog

(sorry — no wild guess predictions

of the future climate —

that’s not real science!):

http://www.elOnionBloggle.Blogspot.com

Nick , you may want to review your markup. Your sin formulae in the Nyquist section are coming out with a umlaut-capital I and a large euro symbol. I’m guessing you want a lower case omega or something. It makes it very hard to read.

Thanks, Greg. The mystery character is just pi. The HTML needs a line

<meta charset=”UTF-8″>

at the top, which I hope a moderator could insert, so that it can read extended Unicode characters. Oddly enough, the comments environment does this automatically, so I didn’t realise it was needed in posts. Here is the same html as it appears in a comment:

If you have a sinusoid frequency f Hz (sin(2πft)) sampled at s Hz, then the samples are sin(2πfn/s), n=0,1,2…

But this is indistinguishable from sin(2π(fn/s+m*n)) for any integer (positive or negative), because you can add a multiple of 2π to the argument of sin without changing its value.

But sin(2π(fn/s+m*n)) = sin(2π(f+m*s)n/s)

Added that, but it doesn’t resolve the problem. I’m going to have to apply my brute force method to make π

Fixed, please check to see if I missed anything.

Thanks, Anthony. Everything seems fixed.

Great, in the future, you can use alt-codes like alt-227 to make π

“Great, in the future, you can use alt-codes like alt-227 to make π”

I tried that, and all it did was make that weird symbol on my screen. I wanted some PIE!! 🙂

Watts, Anthony. Cooking Up A Little `π’: Brute Force Recipes. WUWT WordPress, 2019. ISBN 314159265358-2

While I don’t have a problem with min/max per se, where I can see an potential issue is that the fewer samples you have the less likely your min is near the actual min and the max is near the actual max.

Compounding that is depending on when you take your samples you could be biasing the results without realizing it. For example if you only take 2 samples a day and one sample happens to be minutes away from the real max but the other sample happens to be hours away from the real min, you’ll have a bias towards warmer temps whereas in the reverse case it would bias you towards colder temps and in both cases a bias towards shorter spread of temps (IE real min is 10 real max is 60 for a spread of 50 verse sample min of 30 sample max of 50 for a spread of 20).

Obviously, the more samples you have the better accuracy of your min/max (versus the real min/max) reducing the potential for unintended bias and shortened spread. (instead of having samples that are minutes versus hours away from the min/max you can reduce that to seconds versus minutes for example).

As with all things, it’s a balancing act: in this case between having a high enough frequency to be reasonably accurate without the need for “repair” (which requires assumptions that might not, themselves, be entirely accurate) and the availability of resources to provide that frequency.

With modern tech, high frequency of sampling shouldn’t be all that difficult or expensive to achieve going forward (with less “human-error” in the mix, as computer-controlled sensors can do nearly all the grunt work for you). Obviously past samplings did not have such abilities.

“Obviously past samplings did not have such abilities.” Hey that’s easy, you just need to “homogenise” the data and that will reduce the uncertainty by a factor of 10 , at least 😉

The old min/max thermometers were mechanical and sampled (effectively) infinitely often, saving only two of the samples – the min and the max. Infinite sampling frequency beats Nyquist every time.

While the thermometer may be sampling an infinite number of times, as you say, only two of those numbers were saved. The min and the max.

What happens prior to all but the min and the max being saved isn’t relevant. Only two data points are passed on, and two data points does not satisfy Nyquist.

I call BS. No one sampled “infinitely often”.

Indeed, while the thermometers may have been effective sampling “infinitely often” those samples where being recorded by human-hand only a small number of times a day (and of those, often only the min and max where then saved).

Because you are working with a column of liquid metal, the rate of expansion is about the rate that the molecules of mercury are vibrating. This is in the nanosecond or microsecond range. I’ll allow his rounding off of millions to billions of states per second to infinite.

The thermal lag (thermal inertia/response time) of an old LIG thermometer is such that the recomendation is to allow about 3 to 5 mins for the temperature reading to stabilise.

A LIG thermometer may be sampling on an infinite basis, but its response to change is not instantaneous and therefore it fails to record very short lived episodes.

Consider temperatures taken at airports where the station is situated near the runway/tarmac areas of the airport and the passing of a jet plane on a runaway which blasts warm air (possibly just that coming off the runway itself, not the exhaust of from the engine), an old LIG thermometer will not pick this up, whereas the modern electric thermal couple type thermometer will since the latter has a response time of less than a second.

There is a real issue of splicing together temperature measurements taken by LIG thermometers with those taken by modern electronic instruments.

You think a tube of glass filled with liquid metal responds in a microsecond to a change in temperature of the air it is immersed in?

A nanosecond?

This must be sarcasm.

I may be wrong but I think that’s why he was given to infinity….

When you look at thermometer just like a speedometer it is an instantaneous moment in time. It is a scalar only the next measurement next gives any indication of direction or trend. But we know nothing of the system between one measurement to the next, any one of those billions of trillions states could have come into reality. The atmosphere is not a static system. Nor is it a colum of air moving only in the z-axis. Mixing, thermal density differentials, etc. all come into play.

I think we can be pretty sure you are not a nurse or anyone who has ever been in an actual laboratory.

Actually… there is a difference between FIR and IIR filters. The whole Nyquist hullabaloo here deals with FIR constraints. The whole nature works in terms of IIR filtering, and so do the temperatures. In a previous installment Vukcevic made a valuable note – put a thermometer in a big bucket of water (an IIR filter of a big time constant) and run a single temperature measurement per day. Bolometric measurements of power and energy measurements are gold standard in all other walks of technology – why climate is an exception?

boffin77

But it is possible that the magnetic pins might move, introducing an unknown amount of error. No mechanical system is perfect.

Generally “sampling rate” means how often the “system” is observed. If there is thermal inertia, that is part of the system, not the sampler. If there are errors due to magnetic pins moving, that introduces an error, but does not change the sampling rate. If the LIG thermometer has e.g. stiction and is thus not instantaneous, then that introduces an error (or if intentional then that introduces a low-pass filter upstream of the sampler) but does not change the sampling rate.

To assess the sampling rate, in a mechanical system (which I suggest is not a helpful exercise as illustrated by many comments) then you might ask a question such as: if the liquid magically rises by one degree for a very short time t, and then drops again, what is the longest value of t that might be completely missed by the detector?

All physical thermometers have some amount of thermal inertia, which means that their “max” is something other than the true max unless the thermometer is soaked at that max for a very long time. Which, of course, they are not.

It is also the case that the Nyquist folding theorem applies to stationary systems, and nothing could be farther from the truth, particularly on seasonal-, let alone climatological-, time scales. As anyone who understands “climate” knows. Particularly all of us who are accused of being “climate deniers”. These min/max historical thermometer readings, and the old bucket sea surface temperatures, may be a source of present-day employment, and they are better than nothing, but not much. The paintings of ice fairs on the Thames River probably have much more significance in understanding climate change, than 90% of the min/max surface temperatures.

Except being mechanical it was only accurate to around a quarter of a degree from a test I did to see the difference between a quite expensive mechanical one I had and its new fancy electronic equivalent.

It sometime stuck low and at others seemed to overshoot. Quite how the mechanism of moving the pin worked in practice I am not really sure given the meniscus on top of the mercury and friction holding the pin in place.

Also two different electronic thermometers had different response times one similar to the mechanical one and one much faster which showed higher peaks but strangely not so different low ones.

I am of the opinion that concerns about Nyquist sampling rate are irrelevant to analysis of max/min daily temperatures. The question should be how does max/min daily sampling compare with a true average. Data from the USCRN allow us to examine that question. I did some quick studying along those lines:

http://climate.n0gw.net/TOBS.pdf

Gary, the major question for me is that everyone for TOBS says that you can get a false reading by getting a low or high from the previous day etc, which you have shown.

The big question for me is “How Often Did It Actually Happen”?

Because they adjust all the readings, which means that they could be adding a much bigger bias when the frequency of a actual TOBS errors is low.

Say it happens once per month, that means that they correct one value and make incorrect 27-30 others.

So do we have any idea how often it actually happened?

A C

Nope, I don’t know and neither does anyone else. The mitigating factor here is the correction is applied as a small bias on monthly data, though that amount is based upon some thin guesswork.

Tony Heller did an analysis of this very question, and what he found was that when comparing two sets of records, it can be shown that TOB is completely bogus.

So many issues with it that are clearly intended to artificially create a warming trend that matches the CO2 concentration graph.

Like how the TOB adjustment somehow went from .3 F to .3 C, sometime between USHCN V2 and V3.

Here is a link to a whole bunch of postings he has done on the subject.

The top one has a graph where he simply compared the stations which measured in the afternoon to the ones which measured in the morning.

The only real difference in the two sets is that stations recording in the morning tend to me more southerly, and hence hotter, because in hot places people like to go out in the morning more.

https://realclimatescience.com/2018/07/the-completely-fake-time-of-observation-bias/

https://realclimatescience.com/?s=Time+of+observation

Many thanks to Nick for taking what must have been quite a bit of trouble to lay all this out. And many thanks to WUWT for featuring a contribution from one of the community’s leading contrarians!

Its this spirit of inclusion, that you won’t find on Ars or Real Climate, or the Guardian, and of course never on Skeptical Science, that keeps many of us coming back here. We positively like being challenged and made to think, and we greatly value WUWT for being a place which will feature alternative points of view.

Good on you!

Let’s endorse that comment. Whether we agree with him or not, nick is one of the only people offering counter views here and it makes us stop and think. He is also patient and polite.

Tonyb

Interesting article Nick. However, in order to remove the daily cycle you do need hires data. There is not guarantee that past diurnal cycle was the same as present. I’m not clear on what use you are suggesting could be made of this.

What kind of aliasing issues do you think could result from taking “monthly” ( 30/31 day ) averages in the presence of 27 or 29 day lunar induced variations?

Greg,

Most of the error in monthly average results from the interaction of the sampling frequency with harmonics of the diurnal frequency. So if you subtract even a rough version of the latter, you get rid of much of the error. Even one year gives you 30 days to estimate the diurnal cycle for a particular month. I just calculated the first few Fourier coefficients of this (I used 2010-2018) based on hourly sampling. Then when you subtract that trig approx, you can use coarse (eg 2/day) sampling with not much aliasing from diurnal, and the trig approx itself can be integrated exactly to complete the sum.

but weather can vary so much over a few days, here we’ve had freezing conditions for days, but a front has come through and we have balmy temps today.

This post by Nick (whom I know is a controversial poster) is a perfect example of why I read WUWT. As an old CFO, I understand sampling & statistical tricks, but I respect Nick’s reasonably objective approach to the discussion..

It’ll be interesting to read other, more qualified WUWT responses to Nick, but I appreciate that this discussion has been started at a technical level.

Javert, I agree. In fact, I now look forward to reading his comments and his infrequent posts. It helps me remain balanced, but at first I resisted it. Can’t be just another echo chamber person.

I’m also enjoying reading Mr. Mosher, now that he’s not just tossing in fly by snark but lengthy input.

Given our current climate of censorship, this is refreshing. Truly, wuwt is the highest quality content site on the matter

I didn’t read the whole post, but the idea of Nyquist being important in temperature sampling is wrong. Nyquist tells us how often periodic samples are needed to reconstruct the waveform. Who cares about reconstructing the whole temperature waveform?

Still I think min & max and time of min & max plus some periodic sampling makes sense. That way more reliable statistics such as mean and standard deviation can be developed. (Tmin + Tmax)/2 is not an accurate mean.

Also humidity is important to measure as well as temperature.

If you want to accurately calculate the daily average temperature, you need to be able to accurately reconstruct the waveform.

If you want to accurately calculate a monthly average temperature, you need accurate daily average temperatures.

honest questions:

Have we ever had truly accurate daily average temperatures?

If so, when and what time period?

If so, are there separate methods of collecting this data that are different but also considered accurate and how are they reconciled against each other?

Additionally, how can it be stated we have resolution down to .0x C? that seems highly improbable going back any length of time

The newer sensors log hourly readings, which is good enough for government work.

I believe they started rolling out the newer style sensors sometime in the 1970’s.

The claim is that if you average together a bunch of readings that are accurate to 1 degree C, then you can improve the accuracy. Bogus, but they still make that claim.

You are right, this claim is bogus. I am working on an essay that I’ll finish one of these days.

To calculate an uncertainty of the mean (increased accuracy of a reading) you must measure the SAME thing with the same instrument multiple times. The assumptions are that the errors will be normally distributed and independent. The sharper the peak of the frequency distribution the more likely you are to get the correct answer.

However, daily temperature reading are not the same thing! Why not? Because the reading tomorrow can’t be used to increase the accuracy of today’s readings. That would be akin to measuring an apple and a lime and recording the values to the nearest inch, then averaging the measurements and saying I just reduced the error of each by doing the average of the two. It makes no sense. You would be saying I reduced the error on the apple from 3 inches +- 0.5 inch to 3 inches +- 0.25 inches.

The frequency distribution of measurement errors is not a normal distribution when you only have one measurement. It is a straight line at “1” across the entire error range of a single measurement. In other words if the recorded temperature is 50 +- 0.5 degrees, the actual temperature can be anything between 49.5 and 50.5 with equal probability and no way to reduce the error.

Can you reduce temperature measurement error by averaging? NO! You are not measuring the same thing. It is akin to averaging the apple and lime. Using uncertainty of the mean calculations to determine a more accurate measure simply doesn’t apply with these kind of measurements.

So what is the upshot. The uncertainty of each measure must carry thru the averaging process. It means that each daily average has an error of +- 0.5, each monthly average has an error of +- 0.5, and so on. What does it do to determining a baseline? It means the baseline has an error of +- 0.5 What does it do to anomalies? It means anomalies have a built in error of +- 0.5 degrees. What does it do to trends? The trends have an error of +- 0.5 degrees.

What’s worse? Taking data and trends that have an accuracy of +- 0.5 and splicing on trends that have an accuracy of +- 0.1 degrees and trying to say the whole mess has an accuracy of +- 0.1 degrees. That’s Mann’s trick!

When I see projections that declare accuracy to +-0.02 degrees, I laugh. You simply can not do this with the data measurements as they are. These folks have no idea how to treat measurement error and even worse how to program models to take them into account.

Nyquist errors are great to discuss but they are probably subsumed in the measurement errors from the past.

Thank you Mark and Jim for the response. This is the major issue I’ve seen, among many, that initially zipped past me. Upon further inspection this seems so glaring I don’t know how I missed it.

To be fair I used to only read or watch MSM. Imagine that

Stick around, and hear from all of the people that will argue over and over again for days and weeks on end that measuring temps in different places and on different days, can all be used to reduce the error bars in global average temps to an arbitrarily small number, even if the original measurement resolutions are orders of magnitude higher.

They refuse to accept that it is not a whole bunch of measurements of the same thing, nor to acknowledge that the techniques used are only valid under circumstances that do not apply, normal distribution, not auto correlated, etc.

These same people also commonly confuse and conflate terms such as precision and accuracy.

Just wait, they will be here.

And to follow up…

Even if they were mathematically valid, followed high metrology standards, on well maintained and validated instruments average global temperature has very little meaning on a mechanical system as large as the Earth.

Sure that Earth has warm a bit since 1850 but nothing I read suggests that the climate anywhere has changed. The Sahara is the Sahara, tropics are still here, the temperate zones are still temperate and have seasons…

I’ve done some studying lately about the Law of Large Numbers and how it’s used to reduce the error in the mean. It’s also described as a probability tool, and a way to determine the increase in the probability that a single measurement will be close to the expected value.

In both those cases, the emphasis is on “the expected value,” whether it’s the probability of flipping a coin and getting heads or measuring the length of a board.

However, in climate science, there IS no “expected value.” Taking one max/min/avg temperature measurement per day and then averaging them and determining anomalies from them is like giving the person at each weather station a board to measure once day, and that board being up to one meter different from another. What’s the “expected value” that we’re approaching in this case? Sure, we can run the calculations, but there’s know way of knowing if there’s even a board out there equal to the length of the numbers we generate.

But I think there’s another, less obvious misuse of the Law of Large Numbers. To stick with the metaphor of the vastly different boards being measured, the LLN is only being applied piecemeal. Rather than taking all of the measurements from all of the boards that were measured, only the measurements from one board were used to create a local baseline for that station, and then its anomalies are created. After generating the local anomaly, the local anomalies from the rest of the world are then averaged and schussed and plotzed and whatever to make the global board anomaly — and then the LLN is applied to get that error in the mean as small as possible.

I’ll bet the statistics would be much different if a true global baseline was generated from the measurements from all of the world’s stations put together, and then the individual stations were compared with that. I’ll bet that standard deviation and error in the mean would look a lot different then.

Quote James Schrumpf:

“In both those cases, the emphasis is on “the expected value,”….

*****

In my mind this is one the logic fallacies in the AGW realm. The atmospheric temperature just “is” due to a whole bunch of inputs/outputs that are neither good or bad they just “are”.

We humans are not arbiters of that “is”.

While this discussion is may be useful for pushing statistics and math to a more rigorous discipline I am sure not it furthers climate theory. Especially until we have more rigorous instrument quality control. In addition to temperatures, I would like wind speed, humidity, barometric pressure, a way to measure the uplift of the air mass, perhaps some IR measurements looking up/down.

Don’t get me started… again… too late…

Temperature “anomalies” are derived from an incredibly insignificant blip of time on Earth, and using this incredibly small and meaningless set of numbers to understand an almost incomprehensible reality, is simply nonsense and self delusion.

a·nom·a·ly əˈnäməlē/ noun

1. -something that deviates from what is standard, normal, or expected.

1- There is no such thing as “normal” in climate or weather.

2- What exactly am I supposed to expect in the future, based upon the range of possibilities we see in the geologic record? Can the changes we see happening now be called “extreme” in any way?

3- No.

Anomalies are created by the definers of “normal”, and the deniers of climate history.

James S. –> “I’ve done some studying lately about the Law of Large Numbers and how it’s used to reduce the error in the mean. It’s also described as a probability tool, and a way to determine the increase in the probability that a single measurement will be close to the expected value. ”

You missed the point. The law of large numbers and the uncertainty of the mean only deal with measurements of the same thing. If you pass around a board and a ruler to many people and ask them to measure it, you “may” be able to determine that the error of the mean is close to the true value. However, this requires that the errors are random and have a normal distribution.

You can’t measure one board and record it’s length to the nearest inch, then measure another board and say the errors offset so that you more closely know the true measurement of either board. You have no way to know if the first board was 40.6 and recorded as 41 or if it was 41.4 and recorded also as 41. And remember, it could be anywhere between those values. So each and every value you come up with will have the same probability with no way to cancel it out. The same applies to the second board.

When you average the two values, the average will never be better than the original measurement error, i.e. +/- 0.5 inches. That is because (41.4 + 41.4)/2 is just as likely as (40.6 + 40.6)/2 and is just as likely as (41.0 +41.0)/2.

Using the law of large numbers and the uncertainty of the mean calculations to reduce error requires:

1. measuring the same thing,

2. Multiple measurements of the same thing,

3. a normal distribution of errors.

Measuring temperatures at different times means you are not measuring the same thing, not doing multiple measurements of the same thing, and you have no errors to statistically use so you can’t have a normal distribution.

Jim Gorman ->”You missed the point. The law of large numbers and the uncertainty of the mean only deal with measurements of the same thing. If you pass around a board and a ruler to many people and ask them to measure it, you “may” be able to determine that the error of the mean is close to the true value. However, this requires that the errors are random and have a normal distribution.

“You can’t measure one board and record it’s length to the nearest inch, then measure another board and say the errors offset”

I thought I was saying something like that when I wrote ” Taking one max/min/avg temperature measurement per day and then averaging them and determining anomalies from them is like giving the person at each weather station a board to measure once day, and that board being up to one meter different from another. What’s the “expected value” that we’re approaching in this case? Sure, we can run the calculations, but there’s know way of knowing if there’s even a board out there equal to the length of the numbers we generate.”

I’m pretty sure we’re in agreement on this one.

Jim,

You said: “Nyquist errors are great to discuss but they are probably subsumed in the measurement errors from the past.”

In my post, that Nick referenced, in one of my replies I stated my list of 12 things that are wrong with our temperature records. (I probably forgot one or two that could be added to the list). The general thrust of that post and the one Nick made here, is to focus on Nyquist exclusively. I believe all of the sources of error are cumulative. Maybe this would put us in agreement, Jim. I just wanted to make sure you know we are focusing on one thing here to study it. Maybe in the future and attempt will be made by someone to look at the record error comprehensively (all sources). In my experience, I have seen very little made of Nyquist violation as it relates to the instrumental record. So I wanted to detail that and hopefully add this to the ongoing discussion.

Climate Alarmists (and I’m not referring to anyone in particular – just generically) claim that science is completely on their side. Nyquist is one thing that refutes that – and one that cannot easily be dismissed because a comparison between methods can be made that shows the error in a mathematically conclusive and unambiguous way. All of the other problems with the record can be dismissed by Alarmists because there is no conclusive way to measure the effective error.

“The law of large numbers and the uncertainty of the mean only deal with measurements of the same thing.”

“However, this requires that the errors are random and have a normal distribution.”

Often said here, but never with any support or justification quoted. And it just isn’t true. There is no requirement of “same thing”, nor of normal distribution. The law just reflects the arithmetic of cancelling ups and downs.

William Ward –> I didn’t mean to demean the value of determining the Nyquist requirements for calculating the necessary measurements. I think the value being placed on the past temperature data is ridiculous for many reasons of different errors. It is not fit for the purpose for which it is being used. I agree with your Nyquist analysis. I learned about Nyquist at the telephone company is the days when we were moving from analog carriers and switches into digital carriers and switches.

These errors along with measurement errors have never been addressed in a formal fashion in any paper I can find. I have all the BEST papers I can find and I only find statistical manipulations as if these are just plain old numbers being dealt with. No discussion at all about how the measurement errors affect the input data or how it affects the output data. I have yet to see a paper that discusses how broad temperature errors affect the outcomes of studies. Let alone how does the “global temperature” get divided down into a, for example, 100 acre plot where a certain type of bug population has changed. Too many studies simply say, “Oh global temperatures have risen by 1.5 degrees, so the average temperature in Timbuktu must be increased by 1.5 degrees also”. How scientific.

NS –>

Remember, temperature measurements are not of the same thing. Each one is independent and non-repeatable once it has been recorded. That means N=1 when you are calculating error of the means.

Here are some references.

http://bulldog2.redlands.edu/fac/eric_hill/Phys233/Lab/LabRefCh6%20Uncertainty%20of%20Mean.pdf

Please note the following qualifiers:

1) “This means that if you take a set of N measurements of the same quantity and those measurements are subject to random effects, it is likely that the set will contain some values that are too high and some that are too low compared to the true value. If you think of each measurement value in the set as being the sum of the measurement’s true value and some random error, what we are saying is that the error of a given measurement is as likely to be positive as negative if it is truly random. ”

2) “There are three different kinds of measurements that are not repeatable. The first are intrinsically unrepeatable measurements of one-time events. For example, imagine that you are timing the duration of a foot-race with a single stopwatch. When the first runner crosses the finish line, you stop the watch and look at the value registered. There is no way to repeat this measurement of this particular race duration: the value that you see on your stopwatch is the only measurement that you have and could ever have of this quantity.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Normal_distribution

Please note the following qualifier:

1) “Physical quantities that are expected to be the sum of many independent processes (such as measurement errors) often have distributions that are nearly normal.[3] Moreover, many results and methods (such as propagation of uncertainty and least squares parameter fitting) can be derived analytically in explicit form when the relevant variables are normally distributed. ”

https://users.physics.unc.edu/~deardorf/uncertainty/definitions.html

https://www.physics.umd.edu/courses/Phys276/Hill/Information/Notes/ErrorAnalysis.html

Please note the following qualifier:

1) “Random errors often have a Gaussian normal distribution (see Fig. 2). In such cases statistical methods may be used to analyze the data. The mean m of a number of measurements of the same quantity is the best estimate of that quantity, and the standard deviation s of the measurements shows the accuracy of the estimate. The standard error of the estimate m is s/sqrt(n), where n is the number of measurements. ”

https://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Errors%2c+Theory+of

http://felix.physics.sunysb.edu/~allen/252/PHY_error_analysis.html

Jim Gorman,

“Here are some references.”

None of them say that “The law of large numbers and the uncertainty of the mean only deal with measurements of the same thing.”. In fact, I didn’t see a statement of the LoLN at all. The first is a lecture from a course on measurement. It says how you can calculate the uncertainty for repeated measurements using LoLN. It doesn’t say anywhere that the LoLN is restricted to this.

Your next, Wiki link, says exactly the opposite, and affirms that the LLlON applies regardless of any notion of repeating the same measurement. It says:

“The normal distribution is useful because of the central limit theorem. In its most general form, under some conditions (which include finite variance), it states that averages of samples of observations of random variables independently drawn from independent distributions converge in distribution to the normal”

Nothe that they ate talking explicitly about the mean of non-normal variates (the mean tends to normal). And in the later Central Limit Theorem, there is a para starting:

“The central limit theorem states that under certain (fairly common) conditions, the sum of many random variables will have an approximately normal distribution. More specifically, …”

There is too much math to display here. But they say that if you have N iid (not normal) random variables variance σ, take the mean, and multiply by √N, the result Z has variance σ. So the mean has variance σ/√N. It converges to zero, which is the LoLN result. They give various ways the iid requirement can be relaxed.

The unc reference is also metrology. It has no LoLN, but simply says:

“standard error (standard deviation of the mean) – the sample standard deviation divided by the square root of the number of data points”

Same formula – no requirement of normality or “measuring the same thing”.

The UMD reference says that you can use these formulae for repeated, normal measurements, which is their case. It doesn’t say that usage is restricted to that.

The FreeDict, which is from the Soviet Encyclopdedia (!), again makes no general statement of LoLN.

Finally, the sunnysb ref, again no statement. But see the propagation of errors part. This says that “Even simple experiments usually call for the measurement of more than one quantity. The experimenter inserts these measured values into a formula to compute a desired result.”

And shows how the same formulae apply in combining such derived results.

So in summary – first, no requirement of normality, anywhere. Nor a general statement of LoLN. What has happened is that you have looked up stuff on repeated measurements, seen LoLN formulae used, and inferred that LoLN is restricted to such cases. It isn’t.

NS –> Rather than refuting each of your points, let me point out that I’m not trying to derail the central limit theorem or the law of large numbers. However, you are not seeing the forest for the trees.

Here is a story. A factory was producing rods that were to be a certain length. Last week they produced 1000 of them. The boss came to the production manager and said why did we get back 2/3 of the rods because some were too long and some too short. The manager said “I don’t know. I measured each one to the nearest inch, found the mean and the error of the mean. The error comes out to +/- 0.0002 inches.” The boss said, “Dummy, you just found out how accurate the mean was, not the error range of the production run.”

You are trying to prove the same thing. By averaging 1000 different independent temperature readings you can find a very accurate mean value. However, the real value of your average can vary from the average of the highest possible readings to the average of the lowest possible readings. In other words, the range of the error in each measurement.

Engineers deal with this all the time. I can take 10,000 resistors and measure them. I can average the values and get a very, very accurate mean value. Yet when I tell the designers what the tolerance is, can I use the mean +/- (uncertainty of the mean), or do I specify the average +/- (the actual tolerance) which could be +/- 20%?

I don’t know how else to explain it to you. Uncertainty of the mean and/or law of large numbers only has application to measurements of the same thing. And then they are only useful for finding an estimate of the true value of that one thing. When using single non-repeatable measurements the average is only useful when it is used with the error range of possible values.

Hi Jim,

Thanks for your follow-up comments. I didn’t take that you were demeaning the value of Nyquist, I was just adding some thoughts. I interpret that our views are very much in sync. Thanks for taking the time to clarify though. I do appreciate it. I whole heartedly agree with your follow-up comments. There is so much effort to crunch and analyze data that is bad and so little effort to question the validity of the data being crunched. Climate science has devolved to polishing the turd.

Back before max/min thermometers, it looks like people were more inclined to record the typical temperature of the day. For example, when I wrote my anniversary piece on the Year without a Summer, https://wattsupwiththat.com/2016/06/05/summer-of-1816-in-new-hampshire-a-tale-of-two-freezes/ , I was surprised at the temperature sampling used at various sites.

The one I focused on in Epping NH used “William Plumer’s temperature records were logged at 6:00 AM, 1:00 PM, and 9:00 PM each day. That sounds simple enough, and it turns out that several people in that era logged temperature data at those times or close to it.” One thing I adopted, and was common the, was to compute an average by counting the 9:00PM temperature twice. Clearly people were trying to avoid the extremes at dawn and after noon.

Nick, You have attributed accuracy where there is none you anomaly scenario. You define E as an expected value (average) over a baseline. But is NOT an fixed number but a representative of a distribution (average and standard deviation, etc). That means that T is subject to the inherent error of both E and A and THAT is where I have issue with most climate scientists and the use of anomalies.

If you choose absolute zero for E then T=A and you eliminate the error around E. This shows the error of T = error A which should be the best you can get.

That said, I actually agree with your conclusions on station sampling data and frequency.

My belief is that you cannot squeeze more information out of data than is actually there.

I don’t buy into data manipulation as a means of materializing non-existent information.

Nick was not suggesting materializing non-existent information. He was suggesting minimizing induced errors that degrade the available information.

All data processing is “data manipulation” , you are not saying anything.

But that’s climate science’s modus operandi.

My belief is that you cannot squeeze more information out of data than is actually there.

Quite correct. Nick is using additional sources of information, not available in the original dataset, to reduce errors in this original dataset.

The actual problem with global annual average temperature as it relates to global warming is not the rate of sampling. I struggled with the rate problem because historically different records took measurements at different hours of the day. Few of them did a Min/Max and the hours of sampling reflected the individuals predliction or daily work schedule. I know from discussion with Hubert Lamb it was an issue with Manley’s Central England temperature.

It is reasonable to argue that the objective is detection of change over time and that can be detected regardless of the rate of sampling as long as it is consistent. Stokes tacitly acknowledges this with his selection of sample period because of misssing data in the earlier record.

No, the real problem with the calculation of a global average is the density of stations. It is inadequate in all but a couple of small areas and they are usually the most compromised by factors like the Urban Heat Island Effect or other site change.

So many things are wrong with average temperature reconstructions, both from statistical necessity and out of ideologically-motivated “adjustment”, that they are totally unfit for the purpose of guiding public policy.

as a person with non-STEM background, and after a few years of researching, I agree with your conclusion John. If the average citizen spent the time I have they would likely reach the same conclusion, because reaching a different conclusion necessarily omits so much collusion, inaccuracy, and fraud to be considered an erroneous conclusion.

What is scary is that when you start to peel back the layers of the official narrative, in almost every field, it becomes obvious just how much of the “narrative” is exactly that, a narrative.

I would argue that is where studying Poly Sci assists in these discussions, because I’m willing to recognize patterns about the politics and money, study history, read the words of people in positions of power and influence and see if they said has manifested, and tie them all in together from all sorts of arenas in life. Whereas, many of the STEM focused commentators on this site refuse to accept the conclusions of all that research and perspective because it makes them uncomfortable, for the exact same reasons I was uncomfortable after finally concluding CAGW was a scam. Additionally, many are hyperfocused on the math and subsequently suffer from tunnel vision. We need a balance of macro and micro perspectives.

It is a serious flaw of the human experience, and that is that not only can we lie to ourselves but we inherently don’t want to believe people are capable of such nefarious intent. More specifically, that we could also be fooled by others so easily. Much of what the good book teaches about good and evil is merely trying to drill into peoples heads how easy the path of deception is compared to a righteous path of honesty.

Matthew,

As a putative social “science”, polisci does at least use statistics. IMO even a single undergrad course in statistics suffices to call BS on the whole CACA house of cards (an ineptly mixed metaphor, I know).

The very few good land stations with long histories could be reconstructed. But on some continents, there might not be even one fit for purpose. It would take at least dozens to derive an even remotely representative land surface “record”. GISS’ Gavin Schmidt believes that only 50 stations would suffice. But that still leaves the 71% of Earth’s surface which is ocean.

The sea “surface” (actually below the surface, obviously) “record” is even more of a shambles than that for a bit above the ground.

IMO we can fairly say that Earth as a whole is a bit warmer now than 160 years ago, at the end of the Little Ice Age Cool Period, but pretending precision and accuracy to tenths of a degree would be laughable, if not such a sadly lethal scam. Moreover, most of whatever warming has occurred happened before WWII, when man-made CO2 was a negligible factor, at best.

It’s thus impossible to separate whatever human effect there might be from warming or cooling which would have occurred in the absence of our emisions. We can’t even know the sign of any human influence, since our particulate pollution as cooled the surface. Western Europe and America have cleaned up their air, but then along came China and India to fill it with soot and sulfur compounds anew.

Matt Drobnick,

“Much of what the good book teaches about good and evil is merely trying to drill into peoples heads how easy the path of deception is compared to a righteous path of honesty.”

It is interesting to note that there are realms in which such matters are dealt with in a serious way, every day of the week, and that is within courts of law.

Juries are instructed that if a witness is shown to have given deceptive testimony, in any particular detail, that witness can be assumed to be completely unreliable about anything and everything they have said. IOW, if you know a person is a liar, it is reasonable to ignore them completely, since they might be lying about everything or mixing truth and lies in ways which are unknowable.

And on this:

“It is a serious flaw of the human experience, and that is that not only can we lie to ourselves but we inherently don’t want to believe people are capable of such nefarious intent. More specifically, that we could also be fooled by others so easily. ”

I think it might well be the case that this is getting at a principle difference in the thought processes between people who are skeptical of such things as CAGW and the warmista narrative in general, and those who tend to have swallowed the whole yarn and cannot be convinced to question any of it, whether it be from MSM hype-meisters, prominent alarmists in the climate science orthodoxy, or any of the various breeds of shills and apologists for The Narrative.

The cognitive dissonance of even intelligent people on such matters, especially if they are politicize to such an enormous degree, can be utterly blinding and deafening to those so affected. They can be shown an veritable infinitude of instances of proven and blatant fraud in such areas as academia, medicine, law, justice, and scientific research, and somehow refuse to accept that there is fraud involved in anything important. Or even that sometimes people who are sure they are correct, are simply wrong. Or that people who have spent a career going out on a limb with predictions of some thing, might be inclined to do anything they can to prevent being proven wrong.

The actual situation we are in is much worse than a few random people maybe getting a few things wrong, or overlooking any information which is contrary to what they are selling.

We know there are people who never cared what was true or not, because it was The Narrative that was important.

We know that huge numbers of people have painted themselves into a corner with the certainty they have expressed about something which is dubious at best.

Given the stakes in all of this, the money, prestige, power, fame, influence, etc…and given the consequences of being proven wrong, of not simply losing some money, or prestigious and lucrative careers, or power and influence, political or otherwise, but of being disgraced and discredited, and in some cases possibly culpable of indictable criminal and civil offenses.

Following a train of thought to it’s logical conclusion takes one rather far afield from the discussion at hand, but it is impossible to understand some things without having a far larger perspective.

Sadly, none of today’s shameless charlatans spewing CACA is liable ever to be held legally accountable to the millions of deaths and trillions in lost treasure which their anti-human scam has cost.

You are not mentioning the measurement errors when temperatures are recorded to the nearest degree. A lot of the early temperature measurements had errors of +- 0.5 degrees and there is really no way to remove this error range since each measurement is a stand alone measurement. You may determine a trend, but only to the same accuracy. Most projections don’t even come close to exceeding this error range so are nothing but noise.

Hi Tim,

This post from Nick and my post that initiated it, focused on temporal aliasing. Spatial aliasing is also a critical problem – but not explored here.

You said: “The actual problem with global annual average temperature as it relates to global warming is not the rate of sampling. …”

My reply: Did you read my post (particularly the FULL paper)? That shows with actual examples from USCRN how sample rate matters. Analysis done by Willis added to that, showing significant improvements from 2-samples/day to 24-samples/day when averaging effects over many stations. If we want to cover all stations and the variations experienced over all days, then improvements are seen up to 288-samples/day.

“Spatial aliasing is also a critical problem – but not explored here.”

What on earth would spatial aliasing with irregularly distributed stations ona sphere even mean?

“What on earth would spatial aliasing with irregularly distributed stations on a sphere even mean?”

Yes, you captured it. Irregularly distributed. But more so, very low coverage of the planet’s surface. Forget for a moment that averaging temperature has no scientific or thermodynamic basis. If you are going to average you should get good coverage of the planet. Why so little coverage in South America and Africa? Why so little coverage of Antarctica? I think I see 28 stations there. The land is the size of the US and 2 Mexico’s combined. The amount of stored thermal energy there is massive – just like the oceans. I think 8-10 stations are averaged in to the datasets (GISS, HADCRUT). How many stations from the US contribute to the average? 500? What is the US, perhaps 1% of the Earth’s surface? What about the air above sea surface? How much of this contributes to the temperature brokers’ work?

Nick, you keep advising us about what this climate data is used for but no one has provided the scientific justification for averaging temperature. Furthermore, no rationalization for neglecting so much of the planet’s surface in the calculations.

Its interesting that 12 hour sampling gives the highest temperature. Min Max is 2 samples a day approximately 12 hours apart.

“Min Max is 2 samples a day approximately 12 hours apart.”

I don’t think so. For min/max thermometer systems, I believe it is the lowest and highest of all measurements taken during a period of time since the system was reset. Uniform time between resets would be an important factor regarding the system accuracy. Imagine a lazy operator taking the min/max temps at 11:59 in the evening, resetting the thermometer and taking the next min/max at 12:01 in the morning. I do not know what controls are or were in place to prevent this although I suspect modern stations record data automatically. If only a single reading thermometer is used I suppose some kind of recording device is used to allow an accurate min/max measurement and they are, again, not necessarily 12 hours apart. If a single reading thermometer is used with no recording device, the min/max is anything the operator wants it to be.

Regardless, it seems that while a min/max approach is a lousy way to tell you whether any day was perceived as hot or cold, it works well to tell how the month was.

If we’re trying to quantify the ‘Global Average Temperature’, then why do we introduce a ‘base period’?

We should be capturing temperature readings across the globe for the same point in time, then we can work to average those values based on spatial weighting. Introducing a period of time adds unnecessary complexity. Since the Earth rotates we would want to capture several of these global temperature snapshots over a 24 hour period to allow for variances of Earth’s surface in sunlight. Each snapshot would produce a unique Global Average Temperature without the potential skewing that a ‘base period’ introduces.

Nick has acknowledged this point in response to my comment on an earlier article, and I’m not condemning the work he is presenting with existing data. I appreciate this idea represents a ‘paradigm’ shift with how we process temperature readings, and we likely wouldn’t be able to derive these values from archived data. However, I hope we’re striving for accuracy as we move forward and this is achievable.

Thomas Horner,

“why do we introduce a ‘base period’?”

I described what happens if you don’t in a post here. It’s needed because stations report over different time periods. If you just subtract their averages over those disparate periods to get the anomalies, it will take out some of the trend. And over time, the anomalies would keep changing as the averages benign subtracted changed.

Nick Stokes – Thanks for your response.

“It’s needed because stations report over different time periods”

That’s the crux of my point, there should be no time period. We should be capturing temperature readings around the globe at the same point in time, then we can consider how to average those values. We’d have a more accurate representation of the total of Earth’s energy, and that’s what we’re trying to derive, right?

It doesn’t really matter what sampling method you use when using anomalies as long as the method is consistent and you deal with the UHI effect. A trend is what you are looking for and as

Nick has pointed out you can obtain that trend with reasonable accuracy despite limited sampling resources. However climate science has demonstrated that they can’t deal with the UHI effect. So that is why satellite measuring of temperature is the only true test.

Allan Tomalty – Thank you for your response.

“A trend is what you are looking for” – correct, I am looking for a trend in total global heat content. I am saying that to derive a trend in total global heat content we should measure total global heat content.

“It doesn’t really matter what sampling method you use when using anomalies as long as the method is consistent ” – I understand what you’re saying, but right now we’re only deriving localized anomalies, not an anomaly in total global heat content.

“..capturing temperature readings around the globe at the same point in time…”

Even reading from different places can be tricky. Embarrass, MN is -14F at 11:30am and Duluth MN is -10F 76 miles away

Thomas,

From an engineering perspective, I concur that a “base period” would allow for more comprehensive analysis. Specifically, it would seem that we should have a calibrated and matched network of instruments located around the world – enough to improve spatial aliasing – and all of these instruments would sample according to 1 high-accuracy global clock. With the data recorded, each station’s local time results could be calculate with the appropriate time-shift. But this approach would allow analysis of thermal energy movement around the globe. I would think Nick, with his background in computational fluid dynamics would appreciate this approach. I would expect it would be difficult to get the image of 3 dimensional fluid flow (or even 2D) if timing were not common to every point in the analysis.

Anyone who thinks they can calculate a daily average temperature to a few tenths of a degree from a min and a max recorded only to the nearest degree is lying to himself.

Anyone who thinks they can calculate a monthly average without accurate daily averages, is lying to everyone else.

Random errors , like averaging to nearest degree, will be reduces by averaging larger amounts of data. Systematic ones will not. That is the whole point of the discussion of aliasing.

Not true. Read my other comments. You are describing the “uncertainty of the mean”. This is associated with multiple measurements of the same thing with errors being random, i.e. a normal distribution around the mean. With errors being a normal distribution they will “cancel” themselves out.

The problem is that each temperature measurement is independent and not the same thing. You can’t reduce the error of today’s measurement by a measurement you take tomorrow!

As I commented at the time, Nyquist is a red herring. If you have two samples per day, the best you can reproduce is a sine wave whose frequency is one cycle per day and whose amplitude and phase are unchanging.

The daily cycle only sort of repeats.

The numerical analysis provided by William Ward is convincing. Daily average temperatures calculated on the basis of Tmax and Tmin are susceptible to quite significant errors. No amount of processing will fix that. Dragging Nyquist and Fourier into the situation only invites bloviation.

CommieBob –

“The daily cycle only sort of repeats.”

And that of course, is the problem. If the daily cycle was the same everyday, there would be no problem using (Tmin+Tmax))/2 as a temperature to determine trends. It occurred to me that where I live, in San Antonio, Texas, during the month of July the daily temperature cycle is very close to the same each day.

That is because we spend all summer under the influence of high pressure, with day after day of clear skies. The low temperature occurs just before sunrise and the high temperature about 3 to 4 hours before sunset.

So if I wanted to know the temperature trend over the past 130 years or so that San Antonio has records, I would look only at the average temperature for July of each year. It’s true that I could only say that I knew the summer time trend, and that the other seasons of the year might have a different trend, But I think I could say with confidence I knew the summer trend.

The point being that (Tmax +Tmin)/2 doesn’t have to equal the integral average of the daily temperature cycle, it just has to represent the same point on the distribution each day. For locations and months where the daily cycle doesn’t come close to repeating everyday, it seems to me that (Tmax +Tmin)/2 would not represent the same point on the daily temperature distribution and thus would not give an accurate monthly average temperature.

Tony Heller has a link on his blog that consists of a program he invented and the data set of all of the US temperature record. Adjusted and unadjusted data.

He has made it free and accessible to anyone who wants it.

You can reference any of it numerous convenient and helpful ways.

Here is a link to the page:

For Windows:

https://realclimatescience.com/unhiding-the-decline-for-windows/

For Linux/Mac:

https://realclimatescience.com/unhiding-the-decline-for-linuxmac/

Does anyone know how to reach Tony Heller by email? I could not find an address on his blog.

Thanks.

You might try tweeting him.

Menicholas,

Good idea. That would mean I would have to get Twitter. So far I have avoided that social media mess. But not a bad idea to use if for a strategic purpose. (Then delete it). But I thought he would have to be “following me” in order for me to send him a message…

BTW…here is a link to a posting he did regarding the Texas temp records, along with an image of a table listing some Texas cities and the length of the records for each one.

Some of them go back to the 1890s, and some to the 1940s, and one to 1901:

The screen grab:

The whole posting, from 2016:

https://realclimatescience.com/2016/10/more-noaa-texas-fraud/

Just to be clear: Because the reasons for measuring temperatures, in Climate Science, is use temperatures as a proxy for “energy retained in the climate system”; then Stokes’ “All this speculation about aliasing only matters when you want to make some quantitative statement that depends on what he was doing between samples.”

Average daily temperature, by any method, does not necessarily represent a true picture of the Temperature Profile of the day — and thus does not accurately represent a measured proxy for energy.

If we are trying to determine something about climate system energy — and intend to use temperatures to 1/100ths of a degree — then there may be very good reasons to use AWS 5-minute values where ever available — and to use proper error bars for all Min/Max averages.

Kip,

“and thus does not accurately represent a measured proxy for energy”

Temperature is just temperature. It’s actually a potential; it tells how fast energy can be transferred across a given resistance (eg skin). It isn’t being used as a proxy for energy.

Given that it is atmospheric temperature that is being measured, the failure to actually calculate enthalpy and convert the measure to kilojoules per kilogram shows that nobody is really serious about measuring energy content.

Nick ==> If you think there is some different reason in Climate Science to track average temperature and repeatedly shout “It’s the hottest year ever!” — I’d love to hear it.

Of course, tourist destinations have a use for average MONTHLY TEMPERATURES across time, but they need Average Daytime Temperature, so the tourists know what type of clothes to bring and what outdoor trivialities might be expected. Farmers and other agriculturists need a god idea of Min and Max temperatures at different times of the year, averaged for years, as well as accurate seasonal forecasts of these — accurate “last frost” dates etc.

Climate science (the real kind) needs good records of Min and Max temperatures, along with a lot of other data, to make Koppen Climate maps.

There are no legitimate reasons for anyone to be calculating Global Average Surface Temperatures (LOTI or otherwise). There is simply no scientific use for the calculated (and very approximate) GAST.

There are some legitimate use for tracking changing climatic conditions in various regions — and for air temperatures, the Minimum and Maximum temperatures, presented as time series (graphs) are more informative, even monthly averages of these can give useful information. But a single number for “monthly average temperature” is useless for any conceivable application.

If GAST is NOT being used as a proxy for energy retained in the climate system, why then is it tracked at all? (other than the obvious propaganda value for the CAGW theorists).

More appropriate are “heating degree days” and “cooling degree days” — for cities and regions.

Nick

You said, ” It [temperature] isn’t being used as a proxy for energy.” Funny, I thought that the recent articles on OHC rising more rapidly than expected were based on temperature measurements.

Clyde,

“the recent articles on OHC rising more rapidly than expected were based on temperature measurement”

Well, the recent article by Roy Spencer included a complaint that they had expressed OHC rise as energy rather than temperature.

There are two relevant laws here;

change in heat content = ∫ρcₚ ΔT dV, ρ density cₚ specific heat capacity

and Fourier’s Law

heat flux = – k∇T

The first is what is used for ocean heat. The temperature is very variably distributed, but heat is a conserved quantity, so it makes sense to add it all up. But there isn’t a temperature associated to the whole ocean that is going to be applied to heating any particular thing.

Surface air temperature is significant because it surrounds us, and determines the rate at which heat is transferred to or from us. That’s why it has been measured and talked about for centuries (Fear no more the heat o’ the sun). And the average surface temperature is just a measure of the extent to which we and the things we care about are getting heated and cooled (the Fourier aspect). It isn’t trying to determine the heat content of something.

Nick ==> You state:

“Surface air temperature is significant because it surrounds us, and determines the rate at which heat is transferred to or from us. That’s why it has been measured and talked about for centuries (Fear no more the heat o’ the sun). And the average surface temperature is just a measure of the extent to which we and the things we care about are getting heated and cooled (the Fourier aspect). It isn’t trying to determine the heat content of something.”

I am afraid I agree with you about why we track temperatures! Not so much as to why we track average temperatures….

That being the case, though, then there is no real reason for Climate Science to be tracking Global Average Surface Temperature … and certainly no reason whatever for alarm or concern over the pleasant fact that that metric has increased by one point whatever degrees since the 1880s….

Stokes

Your remark “Well, the recent article by Roy Spencer included a complaint that they had expressed OHC rise as energy rather than temperature’ is a Red Herring. I claimed that temperature was used as a proxy to calculate energy, and you confirmed it with the integral, although you tried to deflect the fact. This is why I have accused you of sophistry in the past.

If the real purpose is to determine how fast and by how much the air is heating or cooling our bodies, then one ought to be using data which takes into account wind, altitude and humidity.

Humid air has far more energy in it, than dry air at the same temp, and so it impedes our bodies ability to cool itself.

Windy air has more energy too, but it cools us better.

90 F is hot as hell in Florida in Summer, but not bad at all in Las Vegas when the humidity is low.

I have the greatest respect for Nick technically but if he thinks temperature is not being used ( incorrectly ) as a proxy for energy I don’t know where he has been for the last 20 years.

UN targets which are the centre of a global effort for reshape human society and energy use are expressed as temperature increase, be it 2 deg. C or the new “it would be really good to stay well under 2.0 , ie 1.5 for example” target.

All this is allegedly to be remedied by a “carbon free” future on the basis that the radiative forcing of CO2 is the primary problem.