Guest Essay by Kip Hansen

This essay is the third and last in a series of essays about Averages — their use and misuse. My interest is in the logical and scientific errors, the informational errors, that can result from what I have playfully coined “The Laws of Averages”.

Averages

As both the word and the concept “average” are subject to a great deal of confusion and misunderstanding in the general public and both word and concept have seen an overwhelming amount of “loose usage” even in scientific circles, not excluding peer-reviewed journal articles and scientific press releases, I gave a refresher on Averages in Part 1 of this series. If your maths or science background is near the great American average, I suggest you take a quick look at the primer in Part 1 then read Part 2 before proceeding.

Why is it a mathematical sin to average a series of averages?

“Dealing with data can sometimes cause confusion. One common data mistake is averaging averages. This can often be seen when trying to create a regional number from county data.” — Data Don’ts: When You Shouldn’t Average Averages

“Today a client asked me to add an “average of averages” figure to some of his performance reports. I freely admit that a nervous and audible groan escaped my lips as I felt myself at risk of tumbling helplessly into the fifth dimension of “Simpson’s Paradox”– that is, the somewhat confusing statement that averaging the averages of different populations produces the average of the combined population.” — Is an Average of Averages Accurate? (Hint: NO!)

“Simpson’s paradox… is a phenomenon in probability and statistics, in which a trend appears in different groups of data but disappears or reverses when these groups are combined. It is sometimes given the descriptive title reversal paradox or amalgamation paradox.” — the Wiki “Simpson’s Paradox”

Averaging averages is only valid when the sets of data — groups, cohorts, number of measurements — are all exactly equal in size (or very nearly so), contain the same number of elements, represent that same area, same volume, same number of patients, same number of opinions and, as with all averages, the data itself is physically and logically homogenous (not heterogeneous) and physically and logically commensurable (not incommensurable). [if this is unclear, please see Part 1 of this series.]

For example, if one has four 6th Grade classes, each containing exactly 30 pupils, and wished to find the average height of the 6th Grade students, one could go about it two ways: 1) Average each class by summing the heights of the students then finding the average by dividing by 30, then summing the averages and dividing by four to get the overall average – an average of the averages or 2) combine all four classes together in one set of 120 students, sum the heights, and divide by 120. The results will be the same.

The contrary example is four classes of 6th Grade students, each of differing sizes — 30, 40, 20, and 60. Finding four class averages and then averaging the averages gives one answer — quite different from the answer if one summed the height of all 150 students and divided by 150. Why? It is because the individual students in the class with only 20 students and the individual students in the class of 60 students will have differing, unequal effects on the overall average. For the average to be valid, each student should represent 0.66% of the overall average [one divided by 150]. But when averaged by class, each class then accounts for 25% of the overall average. Thus each student in the class of 20 would count for 25%/20 = 1.25% of the overall average whereas each student in the class of 60 each count for only 25%/60 = 0.416% of the overall average. Similarly, students in the classes of 30 and 40 each count as 0.83 % and 0.625%. Each student in the smallest class would affect the overall average twice as much as each student in the largest class — contrary to the ideal of each student having an equal effect on the average.

There are examples of this principle in the first two links for the quotes that prefaced this section. (here and here)

For our readers in Indiana (that’s one of the states in the US), we could look at Per Capita Personal Income of the Indianapolis metro area:

This information is provided by the Indiana Business Research Center in an article titled: “Data Don’ts: When You Shouldn’t Average Averages”.

As you can see, if one averages the averages of the counties, one gets a PCPI of $40,027, however, aggregating first and then averaging gives a truer figure of $40,527. This result has a difference — in this case an error — of 1.36%. Of interest to those in Indiana, only the top three earning counties have PCPI higher than the state average, by either system, and eight counties are below the average.

If this seems trivial to you, consider that various claims of “striking new medical discoveries’ and “hottest year ever” are based on just these sorts of differences in effect sizes that are in the range of single digit, or even a fraction of, percentage points or a tenth or one-hundredths of a degree.

To compare with climatology, the published anomalies from the 30-year climate reference period (1981-2011) for the month of June 2017 range from 0.38 °C (ECMWF) to 0.21°C (UAH) with the Tokyo Climate Center weighing in with a middle value of 0.36°C. The range (0.17°C) is nearly 25% of the total temperature increase for the last century. (0.71°C). Even looking at only the two highest figures, 0.38°C and 0.36°C, the difference of 0.02°C is 5% of the total anomaly.

How exactly these averages are produced matters a very great deal in the final result. It matters not at all whether one is averaging absolute values or anomalies — the magnitude of induced error can be huge

Related, but not identical, is Simpson’s Paradox.

Simpson’s Paradox

Simpson’s Paradox, or more correctly the Simpson-Yule effect, is a phenomenon that occurs in statistics and probabilities (and thus with averages), often seen in medical studies and various branches of social sciences, in which a result (a trend or effect difference, for example) seen when comparing groups of data disappears or reverses itself when the groups (of data) are combined.

Some examples of Simpson’s Paradox are famous. One with implications for today’s hot topics involved claimed bias in admission rations ratios for men and women at UC Berkeley. Here’s how one author explained it:

“In 1973, UC Berkeley was sued for gender bias, because their graduate school admission figures showed obvious bias against women.

Men were much more successful in admissions than women, leading Berkeley to be “one of the first universities to be sued for sexual discrimination”. The lawsuit failed, however, when statisticians examined each department separately. Graduate departments have independent admissions systems, so it makes sense to check them separately—and when you do, there appears to be a bias in favor of women.”

In this instance, the combined (amalgamated) data across all departments gave the less informative view of the situation.

Of course, like many famous examples, the UC Berkeley story is a Scientific Urban Legend – the numbers and mathematical phenomenon are true, but there never was a gender bias lawsuit. Real story here.

Another famous example of Simpson’s Paradox was featured (more or less correctly) on the long-running TV series Numb3rs. (full disclosure: I have watched all episodes of this series over the years, some multiple times). I have heard that some people like sports statistics, so this one is for you. It “involves the batting averages of players in professional baseball. It is possible for one player to have a higher batting average than another player each year for a number of years, but to have a lower batting average across all of those years.”

This chart makes the paradox clear:

Each individual year, Justice has a slightly better batting average, but when the three years are combined, Jeter has the slightly better stat. This is Simpson’s Paradox, results reversing when multiple groups of data are considered separately or aggregated.

Climatology

In climatology, the various groups go to great lengths to avoid the downsides of averaging averages. As we will see in comments, various representatives of the various methodologies will weight weigh in and defend their methods.

One group will claim that they do not average at all — they engage in “spatial prediction” which somehow magically produces a prediction that they then simply label as the Global Average Surface Temperature (all while denying having performed averaging). They do, of course, start with daily, monthly, and annual averages — but not real averages…..more on this later.

Another expert might weigh in and say that they definitely don’t average temperatures….they only average anomalies. That is, they find the anomalies first and then average those. If pressed hard enough, this faction will admit that the averaging has long before been accomplished, the local station data — daily average dry bulb temperature — is averaged repeatedly, to arrive at monthly averages, then annual averages, sometimes multiple stations are averaged to achieve a “cell” average, and then these annual or climatic averages are subtracted from the present absolute temperature average (monthly or annual, depending on the process) to leave a remainder, which is called the “ anomaly” — oh, then the anomalies are averaged. The anomalies may or may not, depending on system, actually represent equal areas of the Earth’s surface. [See the first section for the error involved in averaging averages that do not represent the same fraction of the aggregated whole]. This group, and nearly all others, rely on “not real averages” at the root of their method.

Climatology has an averaging problem but the real one is not so much the one discussed above. In climatology, the daily average temperature used in calculations is not an average of the air temperatures experienced or recorded at the weather station during the last 24 hour period under consideration. It is the arithmetic mean of the lowest and highest recorded temperatures (Lo and Hi, the Min Max) for the 24 hour period. It is not the average of all the hourly temperature records, for instance, even when they are recorded and reported. No matter how many measurements are recorded, the daily average is calculated by summing the Lo and the Hi and dividing by two.

Does this make a difference? That is a tricky question.

Temperatures have been recorded as High and Low (Min-Max) for 150 years or more. That’s just how it was done, and in order to remain consistent, that’s how it is done today.

A data download of temperature records for weather station WBAN:64756, Millbrook, NY, for December 2015 through February 2016 gives temperature readings every five minutes. Data set includes values for “DAILYMaximumDryBulbTemp” and “DAILYMinimumDryBulbTemp” followed by “DAILYAverageDryBulbTemp”, all in degrees F. DAILYAverageDryBulbTemp is the arithmetical mean of the two preceding values (Max and Min). It is this last that is used in climatology as the Daily Average Temperature. A typical December day the recorded values look like this:

Daily Max 43 — Daily Min 34 — Daily Average 38 (the arithmetic mean is really 38.5, however, the algorithm apparently rounds x.5 down to x)

However, the Daily Average of All Recorded Temperatures is: 37.3….

The differences on this one day:

Difference between reported Daily Average of Hi-Lo and actual average of recorded Hi-Lo numbers = 0.5 °F due to rounding algorithm.

Difference between reported Daily Average and the more correct Daily Average Using All Recorded Temps = 0.667 °F

Other days in January and February show a range of difference between the reported Daily Average and the Average of All Recorded Temperatures from 0.1°F through 1.25°F to a high noted at 3.17°F on the January 5, 2016.

This is not a scientific sampling — but it is a quick ground truth case study that shows that the numbers being averaged from the very start — the Daily Average Temperatures officially recorded at surface stations, the unmodified basic data themselves, are not calculated to any degree of accuracy or precision at all — but rather are calculated “the way we always have” — finding the mean between the highest and lowest temperatures in a 24-hour period — that does not even give us what we would normally expect as the “average temperature during that day” — but some other number — a simple Mean between the Daily Lo and the Daily Hi, which the above chart reveals to be quite different. The average distance from zero for the two month sample is 1.3°F. The average of all differences, including the sign, is 0.39°F.

The magnitude of these daily differences? Up to or greater than the commonly reported climatic annual global temperature anomalies. It does not matter one whit whether the differences are up or down — it matters that they imply that the numbers being used to influence policy decisions are not accurate all the way down to basic daily temperature reports from single weather stations. Inaccurate data never ever produces accurate results. Personally, I do not think this problem disappears when using “only anomalies” (which some will claim loudly in comments) — the basic, first-floor data is incorrectly, inaccurately, imprecisely calculated.

But, but, but….I know, I can hear the complaints now. The usual chorus of:

- It all averages out in the end (it does not)

- But what about the Law of Large Numbers? (magical thinking)

- We are not concerned with absolute values, only anomalies.

The first two are specious arguments.

The last I will address. The answer lies in the “why” of the differences described above. The reason for the difference (other than the simple rounding up and down of fractional degrees to whole degrees) is that the air temperature at any given weather station is not distributed normally….that is, graphed minute to minute, or hour to hour, one would not see a “normal distribution”, which would look like this:

If air temperature was normally distributed through the day, then the currently used Daily Average Dry Bulb Temperature — the arithmetic mean between the day’s Hi and Lo — would be correct and would not differ from the Daily Average of All Recorded Temperatures for the Day.

But real air surface temperatures look much more like these three days from January and February 2016 in Millbrook, NY:

Air temperature at a weather station does not start at the Lo climb evenly and steadily to the Hi and then slide back down evenly to the next Lo. That is a myth — any outdoorsman (hunter, sailor, camper, explorer, even jogger) knows this fact. Yet in climatology, Daily Average Temperature — and all subsequent weekly, monthly, yearly averages — are calculated based on this false idea. At first, out of necessity — weather stations used Min-Max recording thermometers and were often checked only once per day, and the recording tabs reset at that time — and now out of respect for convention and consistency. We can’t go back and undo the facts — but need to acknowledge that the Daily Averages from those Min-Max/Hi-Lo readings do not represent the actual Daily Average Temperature — neither in accuracy or precision. This insistence on consistency means that the error ranges represented in the above example affect all Global Average Surface Temperature calculations that use station data as their source.

Note: The example used here is of winter days in a temperate climate. The situation is representative, but not necessarily quantitatively — both the signs and the sizes of the effects will be different for different climates, different stations, different seasons. The effect cannot be obviated through statistical manipulation or reducing the station data to anomalies.

Any anomalies derived by subtracting climatic scale averages from current temperatures will not tell us if the average absolute temperature at any one station is rising or falling (or how much). It will tells us only that the mean between the daily hi-low temperatures is rising or falling — which is an entirely different thing. Days with very low lows for an hour or two in early morning followed by high temps most of the rest of the day have the same hi-low mean as days with very low lows for 12 hours and a short hot spike in the afternoon. These two types of days to not have the same actual average temperature. Anomalies cannot illuminate the difference. A climatic shift from one to the other will not show up in anomalies yet the environment would be greatly affected by such a regime shift.

What can we know from the use of these imprecise “daily averages” (and all the other numbers) derived from them?

There are some who question that there is an actual Global Average Surface Temperature. (see “Does a Global Temperature Exist?”)

On the other hand, Steven Mosher so aptly informed us recently:

“The global temperature exists. It has a precise physical meaning. It’s this meaning that allows us to say…The LIA [Little Ice Age] was cooler than today…it’s the meaning that allows us to say the day side of the planet is warmer than the night side…The same meaning that allows us to say Pluto is cooler than Earth and Mercury is warmer.”

What such global averages based on questionably derived “daily averages” cannot tell us is that this year or that year was warmer or cooler by some fraction of a degree. The calculation error –the measurement error — of commonly used station Daily Average Dry Bulb Temperature is equal in magnitude (or nearly so) to the long-term global temperature change. The historic temperature record cannot be corrected for this fault. And modern digital records would require recalculation of Daily Averages from scratch. Even then, the two data sets would not be comparable quantitatively — possibly not even qualitatively.

So, “Yes, It Matters”

It matters a lot how and what one averages. It matters all the way up and down through the magnificent mathematical wonderland that represents the computer programs that read these basic digital records from thousands of weather stations around the world and transmogrify them into a single number.

It matters especially when that single number is then subsequently used as a club to beat the general public and our political leaders into agreement with certain desired policy solutions that will have major — and many believe negative — repercussions on society.

Bottom Line:

It is not enough to correctly mathematically calculate the average of a data set.

It is not enough to be able to defend the methods your Team uses to calculate the [more-often-abused-than-not] Global Averages of data sets.

Even if these averages are of homogeneous data and objects, physically and logically correct, averages return a single number which can then incorrectly be assumed to be a summary or fair representation of the whole set.

Averages, in any and all cases, by their very nature, give only a very narrow view of the information in a data set — and if accepted as representational of the whole, the average will act as a Beam of Darkness, hiding and obscuring the bulk of the information; thus, instead of leading us to a better understanding, they can act to reduce our understanding of the subject under study.

Averaging averages is fraught with danger and must be viewed cautiously. Averaged averages should be considered suspect until proven otherwise.

In climatology, Daily Average Temperatures have been, and continue to be, calculated inaccurately and imprecisely from daily minimum and maximum temperatures which fact casts doubts on the whole Global Average Surface Temperature enterprise.

Averages are good tools but, like hammers or saws, must be used correctly to produce beneficial and useful results. The misuse of averages reduces rather than betters understanding, confuses rather than clarifies and muddies scientific and policy decisions.

UPDATE:

[July 25, 2016 – 12:15 EDT]

Those wanting more data about the differences between Tmean (the Mean between Daily Min and Daily Max) and Taverage (the arithmetic average of all 24 recorded hourly temps — some use T24 for this) — both quantitatively and in annual trends should refer to Spatiotemporal Divergence of the Warming Hiatus over Land Based on Different Definitions of Mean Temperature by Chunlüe Zhou & Kaicun Wang [Nature Scientific Reports | 6:31789 | DOI: 10.1038/srep31789]. Contrary to assertions in comments that trends of these differently defined “average” temperatures are the same, Zhou and Wang show this figure and cation: (h/t David Fair)

Figure 4. The (a,d) annual, (b,e) cold, and (c,f) warm seasonal temperature trends (unit: °C/decade) from the Global Historical Climatology Network-Daily version 3.2 (GHCN-D, [T2]) and the Integrated Surface Database-Hourly (ISD-H, [T24]) are shown for 1998–2013. The GHCN-D is an integrated database of daily climate summaries from land surface stations across the globe, which provides available Tmax and Tmin at approximately 10,400 stations from 1998 to 2013. The ISD-H consists of global hourly and synoptic observations available at approximately 3400 stations from over 100 original data sources. Regions A1, A2 andA3 (inside the green regions shown in the top left subfigure) are selected in this study.

[click here for full sized image]

# # # # #

Author’s Comment Policy:

I am always anxious to read your ideas, opinions, and to answer your questions about the subject of the essay, which in this case is Averages, their uses and misuses.

If you hope that I will respond or reply to your comment, please address your comment explicitly to me — such as “Kip: I wonder if you could explain…..”

As regular visitors know, I do not respond to Climate Warrior comments from either side of the Great Climate Divide — feel free to leave your mandatory talking points but do not expect a response from me.

The ideas presented in this essay, particularly in the Climatology section, are likely to stir controversy and raise objections. For this reason, it is especially important to remain on-point, on-topic in your comments and try to foster civil discussion.

I understand that opinions may vary.

I am interested in examples of the misuse of averages, the proper use of averages, and I expect that many of you will have lots of varying opinions regarding the use of averages in Climate Science.

# # # # #

Discover more from Watts Up With That?

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great post as always.

Typo: “admission rations” should be “admission ratios” I think…

steverichards1984 ==> Good eye, sir! (danged auto-spelling correction!)

The stuff on daily temperatures actually has little to do with averaging averages, and seems to have no point. Yes, the average of max and min does not yield the average that you would get with a time integral. This on its own is not an issue with anomalies. It is, as the post acknowledges, due to the way temperatures were read before digital. We have a long record of min/max temperatures. We have about 25 years of widespread data routinely collected on frequent intervals. You can assemble a record of averages of the 25 year record if you want. People don’t; they prefer the long record, consistently calculated. There may be a small but consistent difference, That is where anomalies come in; the difference will disappear with anomaly.

If you calculated the absolute temperature, it may indeed be that there would be a difference of, say, 0.39°F. Instead of a global average of 57.12F, it would be 57.51F, or whatever. But no sensible person quotes the global average temperature, and it is not an issue with policy. That uses average anomaly. The difference between max/min and time average in each location is a function of the diurnal cycle, and this does not change much over the years. The whole point of taking anomalies is to remove the effect of local consistent variations like this.

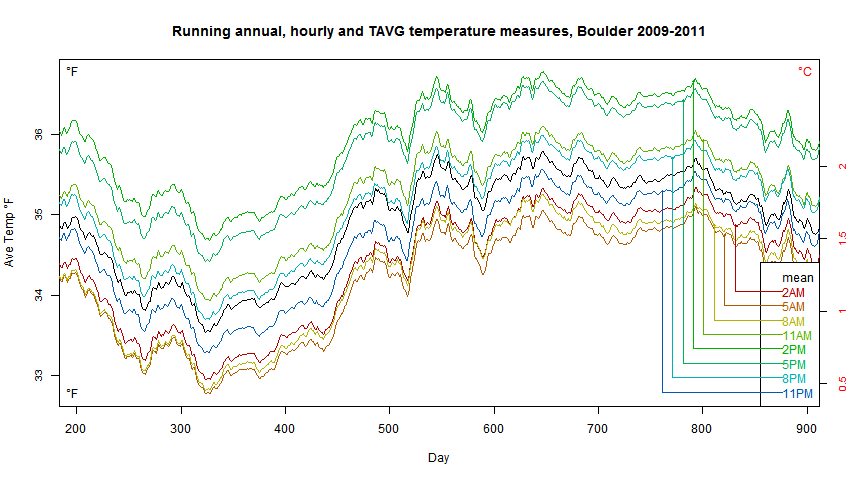

On the difference between min/max and continuous averaging, I did a study of three years at Boulder, Colorado, described here. I produced this plot:

The plack line is what you would get by averaging the 24 hourly readings. The colored lines are what you would get by averaging max and min (hourly) over a 24 hour period. The period ended at different times; I was testing the effect of time of observation (TOBS). In fact changing TOBS has far more effect than the difference between min/max and continuous.

Anyone who thinks this has anything whatever to do with the claim that Mean of Min-Max can be ignored by using anomalies should actually read the description of how the graph was produced at Nick’s link here.

It is a fine demonstration of something — the error I think is that Nick does not slide the 24-hr period for BOTH the Mean of Min-Max and the Average of all Records.

“the error I think is that Nick does not slide the 24-hr period for BOTH the Mean of Min-Max and the Average of all Records.”

Sliding forward the 24-hr period of a 24hr average would have virtually no effect on an annual running mean. The mean for the year is that of the 24*365 hours. That slide would just swap a of those 8760 hours for a few similar ones. There is nothing corresponding to the double counting that is possible with min/max.

Nick ==> So you are just sliding the 24-hr window around for the Min-Max….mushing everything together for years data at a time….nothing to do with my point.

If one uses TMAX and TMIN to produce a daily average, or takes 24 hourly measurements and averages them, how does TOBS ever come into the mix?

Nick Stokes ==> “There may be a small but consistent difference” There is no scientific reason to believe that these differences are consistent — they certainly are not small. To claim so is simply not true. It is no virtue to say that all of our past data is of poor quality, with wide error ranges, in a way that is not linear, is not predictable, and is not subject to correction in present time — so we just ignore this with the magical belief that “it all works out in the end”.

There is no reason to believe that anomalies of this inaccurate and imprecise non-representative data will inform us any better than the raw flawed data. Nothing is corrected or improved by considering anomalies of bad data that does not represent the thing (physical actuality) claimed for it.

The anomalies of the type of average surface temperature currently calculated do not and cannot inform us of the important climatic changes we are interested in.

They tell us not more about how much warmer or cooler the Earth is noi than at some time in the past — except in a very gross way — certainly not in the way claimed by the climate consensus.

Anomalies of the imprecise, inaccurate average temperatures do inform us of changes but only on the scales mentioned by the quote from Steven Mosher.

Kip,

I have a comment above in moderation (all my comments go through moderation lately, for unknown reasons) which demonstrates for Boulder Colorado that for at least three years, the difference is small but consistent.

(They are now all approved) MOD

Nick ==> Your TOBS experiment is interesting but only shows that averages of the Mins and Maxs from day to day by changing the center of the 24-hour period, are consistently related to the changes in averages all all temps when that is done — which is a different issue.

Try comparing DailyAverageDryBulbTemp from a full record (recent) to a real average of all recorded temps as I did. Even within the same month (season) they are wildly different, up and down.

My note in the essay is important as it applies more widely:

Nick Stokes,

You said, “ALL my comments go through moderation lately,…”

It appears that this particular comment did NOT go through moderation. Surely you protest too much!

Nick ==> FYI — I do not moderate my own essays. If you are under constant moderation, and do not know why, you can always address a comment to Charles The Moderator — or just begin with the word Moderator. This will bring your comment to the attention of whomever is moderating.

Kip, I’m waiting on Mr. Mosher’s response to peoples’ use of his statement. From his past discussions of temperature data, I believe he has a greater love affair with it than one would expect from a literal reading of that one comment.

Kip,

” If you are under constant moderation, and do not know why, you can always address a comment to Charles The Moderator”

Thanks. Yes, it’s on all threads, not just this. CTM is aware of the problem, as here. But it seems to be still a mystery.

Clyde

“It appears that this particular comment did NOT go through moderation.”

No, it did. As the MOD says, the comments are all approved and usually very promptly. But they do go through moderation, and so things get out of sequence.

(When you post many comments in a short time, it can cause a short time out getting anything posted,but the Mods have to approve them out of the bin) MOD

Reply: Nick is still moderated. Anthony hasn’t gotten back to me on that yet~ctm

How is this: “…the measure of daily temperature commonly used (Tmax+Tmin)/2 is not exactly what you’d get from integrating the temperature over time. It’s not. But so what? They are both just measures, and you can estimate trends with them.”

Any different from this: “…with the minmax thermometer, if you reset the max when the temperature is falling, it may happen that the temperature may not return to that level for the whole next day.”

Using figures cadged off the chart of Millbrook, NY, for the A line, if one takes the full 24-hr report and averages the temps, one gets 40.0 F. If one takes the TMAX and TMIN and averages those, one gets an average temp of 48.5 F. Looking at the B line, one gets 6.5 F for the TMIN/TMAX average, and 8.5 F if one uses the 24-hr report.

Now it seems to me that if one day can have an average temp difference of 8.5 F depending on whether one uses TMAX and TMIN or the 24-hour average, then trends might be a lot harder to spot than one might think. And surely, if one can handwave that away, then any TOBS difference can be sent packing just as well.

James Schrumpf ==> (threading is getting a bit kooky…) re your at July 25, 2017 at 4:13 pm:

If none of the following matter: accuracy, precision, and correctness of metric for use intended — then we might as well just use random number generators instead of the temp records.

TOBS correctiuons are a work around for using the wrong metric in the first place. Since the late 1990s, digital hourly records were available for almost all stations — to still use min-max is an attempt simply to keep the AGW meme alive and well, really. May be necessary for comparison to historic records — but not for modern climate studies — the historic records have such huge confidence ranges that all the fussing isn;t even really necessary for that — unless one it trying to squeeze out some tiny itty-bitty rise in GAST.

Nick,

“There may be a small but consistent difference, That is where anomalies come in; the difference will disappear with anomaly.”

Those are assumptions that you can’t prove. In my line of work we call that “hand waving”. And Nick, you just created a wind storm with that statement.

Nick Stokes July 24, 2017 at 1:04 pm

“We have about 25 years of widespread data routinely collected on frequent intervals. You can assemble a record of averages of the 25 year record if you want. People don’t; ”

Funny, a lot of CO2 has gone into the air in the last 25 years. I would think this data would be very useful in showing what the temperature rise has been during that time and if there is any correlation or even causation.

I spent 5 years of my career learning the proper way to “average”, and another 20 years trying to get “people who should know” why we have to do it the right way – no shortcuts.

Multiple graphs (of regional data, for example) create new ways for those casually looking at the data (bosses) to be mislead by “best fit of the data to the graph scale” – so good looks bad, and bad goes unnoticed.

A colleague came up with the saying, “You can lead a boss to data, but you can’t make them think”.

Kip,

Warning people about the dangers of taking an average of averages is useful. No one should use tools, like the averaging function, without knowing when they are and are not appropriate (like trying to use a hammer on a screw). But your critique overlooks the most important point–any statistical average carries with it a fundamental uncertainty. It’s not that an average of averages is invalid; it’s that the calculated average is uncertain and would give a different answer if the experiment were run again. The uncertainty of the average is given by the standard deviation of the mean (or standard error) and it does get smaller as the sample size gets bigger: SDM = SD/N^1/2.

Take a look at the examples you gave. Assume the per capita income in those Indiana counties is random. For the SDM of the incomes we get around $2200. That is, the $40,027 number could vary as much as $2200 (actually, there’s a 95% chance it’s +-$4400). The difference between the “average” and the “average of averages” is actually much less than the statistical uncertainty. The flaw is not in taking an average of averages, but in thinking that an average is a precisely determined value. It’s not.

The Berkeley example has the same problem. Taking the “actual” average, as you seem to propose, gives numbers in favor of men: 44.5% versus 30.4%. Taking the averages of averages (by department) appears to favor women slightly: 41.7% to 38.1%. Which one is correct? Neither. And both. Calculating the uncertainties (SDM) for each gives 41.7% +- 11.5% and 38.1% +- 8.9%. See how the 30.4% and 44.5% are both within those uncertainties? More to the point, even the original numbers, based on overall averages only, show no discrepancy. Based on the two SDMs, the total uncertainty (added in quadrature) is 14.5%. The two averages, which look very different, actually agree within 1 SD. There’s no statistical basis for saying the two are different.

In any case, I believe that Simpson’s paradox likely disappears whenever uncertainties are properly used.

Brian,

The calculation of the Standard Error of the Mean is a useful tool for estimating the precision from a large number of measurements of something with a singular value — a constant — by removing the random errors of measurement. However, when measuring a variable, the measurement random errors are swamped by the range of the variable. Only the standard deviation of the data set gives a reasonable estimate of the behavior of the variable.

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2017/04/12/are-claimed-global-record-temperatures-valid/

Clyde,

The calculation of both the mean and the standard deviation for a group of values assumes that some unchanging value can be defined. Of course, we often apply means and standard deviations to things that are changing. In this case, one either applies a model that takes the changes into account, or one assumes that there is in fact an unchanging quantity that can be determined. The SDM is no different than the mean or SD in this regard.

Brian,

You said, “Of course, we often apply means and standard deviations to things that are changing. In this case, one either applies a model that takes the changes into account, or one assumes that there is in fact an unchanging quantity that can be determined.” The $6.4×10^6 question is whether one is justified in doing what is often done.

How did you calculate the uncertainty? To derive that from the standard deviation you must know the distribution function for the data and it doesn’t exactly feel intuitive that university admissions must be normally distributed.

tty,

Since I didn’t have the underlying distribution, I calculated the SD of the sample. The same thing we do whenever the distribution is unknown. Yes, it’s only an estimate, but it gives the right order of magnitude and illustrates the point that all averages must be treated as uncertain.

I guessed as much. SD can of course always be calculated and almost everybody more or less automatically does the “two sigma = 95 % probability” thingy. However this only applies to normally distributed (Gaussian) data which climate data usually is not. Hydrological data for example are usually Hurst-Kolmogorov distributed in which case the 2 SD = 95% will be way off.

Brian,

But they seldom are.

Uncertainty is poorly understood.

Many of the silly concepts like hottest year by 0.01 degrees or whatever have no justification when uncertainty his considered.

Indeed, much of the global temperature data, from daily obs at a site to a world average, remind me of items tossed around in a clothes washer. The drum is the limits of uncertainty, the item you (wrongly) seek can be found if you stick your hand in and grab and grab till you get what you want.

Geoff

I don’t see how one can have uncertainty in the mean when one is counting items and not measuring values. The Berkeley story has a set, finite, perfectly accurate population: 8442 male applicants and 44% admitted, and 4321 female applicants and 35% admitted.

There’s no measurement error here, no instrument with +/- 1mm error. One can calculate the uncertainty in the mean if one so desires, but it has no meaning in this case. It’s not like you’d count them one time and get 8440 males and 4316 females, and so forth.

The actual number of admitted for each gender isn’t given, but 3715/8442 = 0.44006, so that’s probably the actual number of whole human males admitted. 1512/4321 = 0.34991, and is a little closer to .35 than is 1513/4321, so that’s the number of females admitted.

So in this case we do have a clear answer: more men than women were admitted to the graduate programs. Any other answer is just playing with numbers.

James Schrumpf ==> You are right — uncertainty and statistical probabilities have no place in the Berkeley example, and exactly because they are simple counts — there can be no measurement error (only miscounting).

And you are right, ” more men than women were admitted to the graduate programs.”

You are not right that any other view is “just playing with numbers”. The view of gender and admission to each of the departments separately is equally valid — and in may ways, more valid — in an investigation of admission practices to Berkeley’s graduate programs. The precise reason for this is that that subject is “graduate programs” (plural). Now we have to consider that we are not talking about just two numbers in one data set — we are talking about two numbers in multiple data sets — each data set has its own absolutely immutably correct answer to the question at hand.

It is the combining, aggregating these data sets, that can be considered “playing with numbers”, at least equally as well as the reverse.

Of course, my point in the essay is that in all cases involving multiple sets of data, the question arises about aggregation — before averaging? after averaging? average the averages? don’t aggregate at all?

I shouldn’t have said “playing with numbers” but instead, “playing with numbers to indicate that women are more highly represented than they are.”

I have always wondered why the average of T_max and T_min is used. It is worst number to use of the three that were historically recorded. Just looking at T_max by itself would make more sense. However the best number to use is probably T_min which, since it almost always occurs overnight while measurements were taken during the day, requires virtually no Tobs adjustment.

Ian,

In terms of accuracy, T_min is probably better, except in the middle of winter in higher latitudes where values where probably “guesstimated” to avoid going outside to read the thermometer. But in terms of environmental/biological impact (what really affects us), T_max is the more appropriate measurement. If we are all going to fry, it will be from increasing maximum temperatures, not minimums. But they don’t use T_max alone because there’s no real trend there.

Ian H,

A more reasonable approach would be to analyze and report the T_max and T_min separately. They each have a story to tell and averaging them loses information.

Clyde ==> Yes, precisely one of my points. Averaging them also tells you nothing of what went on in-between….

Didn’t I read somewhere that the primary driver for increasing anomalies in urban areas was higher T_mins rather than higher T_maxs? In other words, the trend in T_max is significantly lower than the trend of the average of T_max and T_min.

John,

You are correct.

Ian,

Actually T-min no better than T_max at avoiding TOBS problem. Consider morning observation as was done at many historic sites. If the previous morning was colder than the current day at observation time, even though the minimum for both days may have occurred prior to each observation, reset of the T_min thermometer would have happened at a colder temperature than the low of current day. The previous day’s lower observation time temperature would be recorded for the current day. The same thing happens with T_max with afternoon observation times though, in that case, a previous day’s higher observation time temperature would be recorded for the current day.

Observation times were occasionally often vague and administratively changed. Common observation times were “Morning” (sunrise), “Evening” (sunset), or at some specified time of day. Remember also that time of day in our earlier records was rather fluid. Early in the records, each region and sometimes even each city had their own time zone. Some areas simply set their clocks based upon almanac sunrise and sunset values. Since establishment of the current USA time zones, their boundaries have been shifted several times.

“Temperatures have been recorded as High and Low (Min-Max) for 150 years or more. That’s just how it was done, and in order to remain consistent, that’s how it is done today.”

Not in Sweden. SMHI the Swedish Meteorological Agency has its own home-grown formula for doing this (used since 1947):

Tm=(aT07+bT13+cT19+dTx+eTn)/100

T07, T13 and T19 is the temperature at 7 am, 1 pm and 7 pm. Tx is the maximum temperature and Tn the minimum temperature while a, b, c, d, e is a set of coefficient that is different for each month of the year.

They claim that this gives a more correct average temperature, which is quite probably correct, but it means that data from swedish stations are not comparable with data from the rest of the World.

How does BEST, GISS, HADCRUT etc correct for this I wonder?

tty,

“How does BEST, GISS, HADCRUT etc correct for this I wonder?”

They don’t need to. Sweden, like all countries, reports ave MAX and MIN via CLIMAT forms, as you can see here. That data is what GHCN uses.

Nick ==> Yes, GHCN still uses the average of Min-Max — despite knowing how far off it is. It simply does not represent what is claimed.

I was recently looking at the .dly files for GHCN, specifically those marked GSN, supposedly the “select” stations, based on length of service and positioning for a good distribution across the Earth. One of them, IN020081000.dly, from Kodaikanal, India, has nothing but PRCP records and ends in 1970.

How is this station still listed as part of GSN?

“The uncertainty of the average is given by the standard deviation of the mean (or standard error) and it does get smaller as the sample size gets bigger: SDM = SD/N^1/2.”

That is only correct if the data are iid (Independent and identically distributed random variables), which temperature measurements emphatically are not since they are fairly strongly autocorrelated. So, no, it’s not that simple.

tty,

Yes, I know it’s not quite that simple. The point is meant to be illustrative–any calculation of an average must necessarily be treated as uncertain. Once that is understood, Simpson’s paradox goes away.

I think it could be fun and educating to set up 3 computers to do compilation of the Global anomaly.

The first one works on the stations the usual way making a Global anomaly. The two others copy exactly the steps the first one do with the anomaly but only on the station reference and station temperature.

In that way you would get a Global reference and a Global temperature, and could check if the reference and temperature changes in strange ways.

The anomaly has gone up 1K, but how has the reference changed?

I hope you see how that could resolve some of the doubt about the temporal stability of the anomalies.

Thanks Kip.

I’ve often wondered; even if you could determine the average temperature of a nominal imaginary spheroid shell some 5 feet above the surface, what will it mean. Not with standing the enormity and practical impossibility of the task, it is an arbitrary shell boundary across which energy flows as sensory heat and latent heat with huge chaotic stores each side of the boundary in the form of the earth and oceans on one side and the atmosphere on the other. It is an impossible task to extract meaning from simple minimum and maximum temps. The vexed problem of warming in concept is one of radiation in and out including all the nuances involved.

That should read: the vexed problem of “global warming”…

There is another aspect of this problem that needs to be considered. The mean is a measure of the central tendency of measurement samples. The range and standard deviation are a measure of the variability of the data. Taking an average of a time series of a variable is similar to a bandpass filter. That is, the extreme values are removed. As with a convolution filter, the original data are replaced with calculated values. We then have a distorted view of how the variable changes with time and no longer know what the original values were. That is, they can’t be reconstructed from the averaging results. Filtering is generally an irreversible operation.

I would say that the variation of station or global temperatures over time is of greater importance for understanding the system than is any rationalized attempt to claim high precision in the average(s). Basically, removing the extreme values by two (or more) successive averaging steps loses much information. By focusing on trying to justify knowing the mean to two or three orders of magnitude greater than the precision of the original data, we are creating synthetic data that appears to be better behaved than the real data.

We know that T_max and T_min are behaving differently over time. Might the extreme values be changing? That is, might the range of global temperatures be changing? The way that the data are currently processed and reported, we really don’t know that because of the averaging. The farther one is removed from the original data, the more information that is lost.

Wrong again kip.

I’ll note that you actually did not address the spatial prediction question. We simply produce a spatial prediction. Testing the prediction is in fact a part of the process.

The primary product is a feild. Not a number.

You can go get this feild. It’s what real scientists use.

If you integrate that feild you get the expected value.

This of course is the standard textbook statistics that skeptics like steve mcintyre insisted folks in climate science should use.

Mosher ==> At least you have acted as predicted. You will have to point out exactly what it is you think I am “Wrong again” about.

Don’t make me quote the BEST website and post the BEST graphs again….since they are exactly contrary to your argument here and elsewhere.

If you would like to give us a URL that shows that the BEST process only produces a field — and not anything as gross as a claimed Global Average Surface Temperature — that would be nice. Otherwise we have to accept the BEST does in fact produce a Global Average Surface Temperature product that they compare to other such products from other teams, and that the process used to produce that product is described as

Berkeley Earth Temperature Averaging Process producing the time series graphs shown on the BEST page Summary of Findings.

Note that nothing on the Summary of Findings page indicates that BEST does anything that would not normally be called (by me and, apparently, the rest of the BEST Team) as calculating Global Average Temperature.

Kip: The key problem that you identify is that averaging the high and low temperatures produces a biased estimate of the actual average temperature. Is does not matter how many biased numbers you average, you will not end up with an unbiased result. Biases only average out if they are non-systematic. In other words the average of all biases is zero. You have no way of verifying this if all you have is high and low values to start with.

Walt ==> You have that exactly right if I understand you correctly. There is no way to scientifically assume that the differences between DailyAverageDryBulbTemperature (mean of the Min and Max) and what would be an actual average of all recorded temperatures during the same 24-hr period are 1. consistent, and 2. unbiased or 3. caused by unknown factors even. Certainly the information on the size of the effect, the sign of the effect, and what might be its bias is not contained in the Historic record that shows only Min and Max.

Information about the bias could be found for modern digital records, as I did for my little sample. My sample shows that in the sample 45 days, bias is not consistent even as to sign.

I belive we simply will not be able to know. I also believe that “it all averages out” is utter nonsense.

I haven’t read through all of the comments on this excellent series of reports, so if my comment here has been discussed at any point previously, I’m sorry for piling on . . . but I’m still confused as to whether there is any meaning at all in the concept of “average temperature” or especially “average temperature anomaly”. Temperature, as used in most CAGW arguments, is a proxy for energy. The hypothesis (which seems to be crumbling recently with “the pause”) is that increasing CO2, caused by increasing burning of fossil fuels, is causing an imbalance in the release of radiant energy back to space – which should be easily seen in a gradual worldwide increase in local temperature – if the entire worlds energy distribution picture were completely stagnant. But since it is widely agreed that incoming radiant energy is transferred, phase changed, transported, phase changed and then transferred again and again, is there even such a thing as an “average global temperature”?

Nature does not react to an average temperature at ANY TIME in any specific “climate”. More importantly with respect to “average temperature anomalies”, nature does not react at any time this year to what the “average temperature” was last year or, even worse, what the temperature was at some reference year in the past! The air temperature at any location, any elevation, any pressure, any local wind-speed, and any humidity is a variable that is dependent on these other variables. . . and nature reacts at every temperature, every elevation, and every pressure in completely different ways. The largest green house gas – water – heats up, evaporates, climbs high into the atmosphere, changes phase (absorbing more energy), moves somewhere away from where it originate, may change phase again, or may rain down and cool . . . but in each instance the physics of the energy balance that is fluctuating does NOT respond to an “average temperature” but the exact temperature at that location and instance. When I go out of my house in the heat of summer, I don’t wear my winter coat, snow boots, and warm pants, and there is never snow on the ground when the temperature is between 65 -95 degrees. Likewise I don’t wear shorts, a T-shirt, and sandals in the middle of a snowstorm in the winter.

Natural local climates do not respond to long term “average” temperature changes, but rather to an accumulation of short term changes over very long times. And in many cases it hasn’t been the subtle change in CO2 that has created the dramatic change in local climate, but rather the dramatic change in the local use of water. (Lake Chad, Aral Sea . . . ) Since water evaporates, condenses, freezes, melts and sublimes at well known rates at specific temperatures, (not average temperatures or average temperature anomalies) and specific pressures, I am confused about how the average of a daily high and daily low temperature gives any meaningful information at all from which one can discern energy flow in any given location where “average daily temperature” is recorded in the world. At the very least wouldn’t one have to make an estimate of what the energy of the air mixture was at those two times by measure relative humidity, and pressure and attempting to compute the enthalpy?

https://www.scribd.com/doc/185452956/Carrier-psychrometric-chart-1500m-above-sea-level-pdf

If the measurement were made in the middle of the Sahara on a clear windless day with a constant relative humidity and no change in pressure, then maybe, perhaps the temperature for that day could be “averaged”. But in the vast majority of the rest of the world IMHO, “average temperature” doesn’t come close to approximating local atmospheric energy content. (I’m curious: If the CO2 content of the atmosphere is measured on an hour by hour basis on the top of Mauna Loa, and the local temperature, pressure and RH are also measured at this location, why hasn’t anyone published all four data sets with no “adjustments” from there so we can see just how much of an effect (direct or otherwise) that CO2 and water vapor are having on local temp? Or if they have, could someone please point me to that data?)

It does seem that enthalpy is actually the quantity of interest rather than just temperature. Unfortunately not all air temperature data could be converted to enthalpy because the moisture content of the air is not always measured.

If you regress daily Tmax against daily rainfall at a site, some 10% to 60% of the T variability can be explained by rainfall. Statistically.

So should we use raw Tmax or Tmax corrected for rainfall?

Geoff.

I think there may be a fundamental error in this post that I would like to submit for discussion. When averages are made of static measurements, I think that many of the concepts in this post are very well stated. However, temperatures as used in Climate Science™ are usually a time series. When you average a time series, you are actually applying a filter instead. The math is totally different. You can’t compare the two. In a time series, averaging the max and the min temperature to obtain a “daily” temperature is actually a smoothing operation that tries to eliminate all wavelengths shorter than a day. However, the filter can add wavelengths to the data that are not in the data if the filter is not accurate. I think that is the real issue here. Climate Science™ completely ignores the issue of adding noise to the data by filtering. And when you average the averages, you risk adding noise to the noise.

Another way to think of it is by Fourier Analysis. Any time series can be approximated by a sum of terms consisting of each wavelength multiplied by a corresponding coefficient. I.E.: aλ1 + bλ2 + … +Nλn, where lambda sub n are the various wavelength and a, b, c and so on are the coefficients. A filter ideally just removes (for example) all terms in the equation that are smaller than one day, without adding any other terms that are not in there. However, when the filter (or model) differs from reality, then using that filter (i.e. the assumption that the daily temperature curve is roughly sinusoidal) instead may add noise (terms that don’t belong in the equation). Climate Science™ blithely assumes that all filtering is perfect and reduces uncertainty in the trend (by removing the high amplitude and high frequency terms in the equation that mask the small amplitude but low frequency (i.e. long wavelength) climate signal), without adding any noise whatsoever.

Phil,

I did speak to the idea of averaging being equivalent to a filter (@ur momisugly July 24, 2017 at 3:52 pm ). However, no one has taken me to task for it. However, you raise an interesting point as to whether or not the averaging process can distort more than just the variance of the time series.

You are correct. I posted before reading the whole thread. It was supposed to be a reply to an earlier comment, but it ended up at the end.

Wrong again kip

”

In climatology, Daily Average Temperatures have been, and continue to be, calculated inaccurately and imprecisely from daily minimum and maximum temperatures which fact casts doubts on the whole Global Average Surface Temperature enterprise.”

In climatology if you have minute by minute or hour by hour you calculate two metrics.

Tmean. This is the integrated temperature

Tavg. Tmax + tmin / 2

You can do this yourself using CRN data.

Then you do a test.

Is Tavg an unbiased estimator of tmean?

Is the trend in tmean over time the same as the trend

In tavg?

Is the monthly and annual average taken both ways the same,

That is integrate minute by minute or hour by hour for a month or year or years..And then also do it using Tavg.

Answer? You could read the literature or do the test yourself with open data.

I did the latter and then the former.

Guess what?

Mosher ==> I would guess that the quantitative answers were different and that the true range represented by the Daily Average of Max-Min was different than the Average of All recorded Data by up to 1 whole degree C.

I would guess that the local or grid averages were not represented as the RANGE that is implied by the differences between actual average of al data and the mean of Min-Max.

I would guess that whatever trend found for Mean Min-Max did not show the result as a range as wide as 1 degree C —

You dodge the issue but not very adroitly.

My point is quantitative —- including the width of uncertainty.

Well, what do you know, Mr. Mosher. Did you happen to see this: https://wattsupwiththat.com/2017/07/24/another-paper-confirms-the-pause/

The Chinese must Wander in a Different Weed Patch. How one calculates T ave. does seem to matter. Please listen to Kip more in the future.

Kip, although not considered in your essay, I think one should start with the idea of what we are really should be trying to investigate in climate science over time. If it is to have an early warning system for dangerous developments that may require serious amelioration then the whole idea of metrics should be different than what we are doing anyway.

To clarify what I’m driving at, let us say we are worried that a sea level rise of more than 3m in a century would present problems that would seriously challenge our normal engineering capabilities in ameliorating the problem within a reasonable length of time or size of budget over time. Running down to the sea with a micrometer every year and hyperventilating about a few mm rise is ridiculous. A review of tide gauge data alone with its ups and downs is fully adequate. If in a decade we see, say, a 10cm rise, we might say we should begin to accumulate a certain budget to ensure timely fortifications to take care of 200cm of protection 50yrs out.

For temperature, if 2C is the worry point a century out, let’s take advantage of Arctic amplification of about 3x the (lousy) average. Set up a dozen 24hr T recorders around the Arctic and if the temperature average increase exceeds 2C by 2040, then we will begin replacing coal with Nuclear over a 20yr period. Moreover, we could begin now improving efficiencies, painting our ropes white, planting more trees and other sensible low budget things. I think the past stuff we let go, set up 24hr recording and relax.

Oops ‘rooves’ not ropes.

Am I suprised that Kip doesnt know we collect Tmean and as well as tavg?

or that he doesnt even know that they are compared?

Jesus I brought this topic up on CA a decade ago. Any way.

If you want to build the longest record you are constrained to use the Lowest common denominator.

monthly Tavg. In the early 1800s we start to get Monthly Max and Monthly Min, and after that records

with Daily Max and Daily Min. Into the 1900s you will start to get hourly.

And of course people test. How many missing days can you have and still estimate the monthly correctly?

How many missing months and still get the year correct? How many missing hours can you have an still get the day correct.

Stuff Kip has never read and never will read.

Data kip could not even find and if he found it wouldnt know what to do with.

Bottom line. If we could find a SYSTEMATIC BIAS ( too high or too low) between Tavg and Tmean,

we could and probably would Adjust Tavg to offset this bias. To date no one i know of ( including me, cause long ago I thought this argument of Kips was KILLER) has indetified a Systematic bias. Tavg is an unbiased estimator of Tmean. yes yes.. like All measurements and estimates it has OMG error and uncertainty!!!!

the horror!

As for records. I thnk during the crter administration we had “record” inflation. Now forget the fact that CPI is only an estimate of actual inflation and its only an index that samples a few things, and those things change over time.. We have no problem whatsoever in

A Choosing a metric

B. Acknowledging the imperfections of the metric OMG Tavg is not the same as Tmean!!!! duh

C. Stating records IN THAT METRIC.

you want records in Tmean? There is hourly data going back some time. there is minute by minute data..

Guess what you will find?

here is a simple example… OMG we are hiding the difference between Tmean and tavg in plain sight!!

quick kip call the fraud police.

https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/crn/month-summary?station_id=1026&date=2017-07

AS far back as 1845 Kaemtz tried to come up with correction factors for estimating Tmean from Tavg.

Thats how far back this conspiracy goes!

Kaemtz LF. 1845. A Complete Course of Meteorology. Hippolyte Bailli`ere. Publisher, 219 Regent St.; London

One method involves using 3 measures.

The extremes of day 1, and the min of day 2. and sunrise time sunset times.

Then theres the Kaemtz method, the austrian method..

Bottom line?

Its getting warmer.

There was an LIA.

Mosher ==> At last we agree — the current method is adequate for determining that there was a LIA and that it is warmer, generally, today than then.

I even quote you on it in the essay:

.

Credit where credit is due.

And there is zero evidence that humans have had any effect on global average temperature since 1850 or 1950. Indeed all the evidence in the world is against the repeatedly falsified hypothesis that humans have any measurable effect on GASTA.

Mr. Mosher Wanders in the Weeds for decades and produces ….. the obvious!

Mosher ==> Can’t you for a moment quit fighting the Climate Wars. I have not called fraud or any other of your conspiracy-based fantasies. No one thinks that climatology can’t average a set of numbers….its just that the choice of metrics means that they do not use the average. That’s exact;ly what I say — as I’m sure you know.

Your link clearly and succinctly illustrates that Average Temperature is different from Mean temperature (Min-Max), in the month your link leads to 0.8 degrees C. That is equal in size to the entire anomaly since 1950.

My point is that The Mean is used, and not the average — yet the claim is always it somehow represents the Average. Tmean is better represented as a Range, not as a precise figure.

It should not outrage you that I point this out — you seem to know all about it, as any knowledgeable person is.

For Average Temperature or Mean Temperature, the real question should be whether the days are getting hotter or the nights are just not as cool. The former suggests a truly warming world; the latter suggests a UHI artifact in the data that has not been corrected.

Does https://wattsupwiththat.com/2017/07/24/another-paper-confirms-the-pause/ help?

Dave Fair ==> Thank you for that link — exactly the paper I was searching for. (highlighted here at WUWT while I was off sailing for two months this spring…missed it!)

Figure 4 shows exactly what I imply [link to full sized image] about the differences between Taverage and Tmean. In the Zhou and Wang paper, they use T2 for the mean of Min-Max and T24 for the average of hourly temps.

Click link in text for full sized image with original caption.

“If you want to build the longest record you are constrained to use the Lowest common denominator.”

And if you are actually interested in the science of of the Earth’s climate you would discard poor quality data and focus on improving the quantity and quality of the data.

The satellite program was an attempt to do this. But when the data did not match the confirmation bias of climate scientists the data was first ignored then attacked.

When the ARGO floats data showed cooling the data were adjusted to show warming.

USCRN was supposed to be the Gold Standard of surface temperature data. It showed cooling and was ignored.

See a pattern here?

After extensive research I have calculated that the Globally the average height of an adult male is 5 9″ and 3/4 inches.

A very useful thing to know.

I resemble that!

Sure, why not? I promise not to mention that no one seems to know where 2C came from. (I suspect it was someone’s WAG decades ago that the Eemian interglacial peaked 2 degrees C above current). Nor do we know that Arctic Amplification is 3x rather than 0.3x or 30x. And, of course,

Sorry — didn’t mean to post that because I decided the train of thought wasn’t going anywhere useful or meaningful.

I loath WordPress.

Don K ==> In that case, we will ignore it.

Lindzen pointed out it is unwise to reduce climate change to a single metric – global average temperature. The spatial distribution of temperatures is more meaningful than the global average temperature. The polar region is always cold and the equator is always warm. The difference in temperature between the poles and the equator characterizes the glacial and interglacial periods – whether the mid latitudes will be covered by a mile-thick ice or by trees and grasses. Global warming that reduces this temperature difference is a good thing.

None of this post or comments touches on the use of geostatistics to generate an average global temperature from the (very) erratically distributed data points. While statistics deals with populations of numbers, geostatistics deals with populations of numbers, every one of which has a position in space as well as a value. The core of geostatistics is a process called kriging which is used to generate a grid of uniformly spaced points, from which an “average” can be derived. Kriging can be done in 2 or 3 dimensions.

As I understand it, kriging is used by the climate industry, to generate the global average temperatures. I would hazard a guess that most of the users of kriging don’t really understand it, but accept that it’s a better way of filling empty cells in a grid than straight gridding using things like polynomial-fitting or minimum-curvature.

Geostatistics, and its core method of kriging was initially developed (by a guy called Krige) to analyse the distribution of gold grades in South African gold mines It’s very widely used in mining now, mainly to estimate average grades in ore reserve calculations, from erratically distributed data points. Is it suitable for analysing temperature data? I have no idea, but there will be people out there who understand it much better than I do

Anyone interested can Google “kriging” or “geostatistics”.and get a feel for how it works.

In the end Smart, Kriging is just interpolation, a pretty well understood way to guess at the values of some metric between two points you actually measured. Other words for it like “infilling” mean the same thing; the investigator is assuming the thing being measured varies in some linear way between two measured points. It’s a guess.

In the real world of geology and temperature, there are anomalous events; things that just don’t follow a linear relationship. For example, you may find two veins of gold separated by some distance. You have actual measures for those two veins and you decide to interpolate the expected value of gold that might be found between those two points. This wouldn’t consider the possibility there might be a third vein that’s much richer between them, or there might be nothing but solid quartz/granite there. No one really knows. Until you actually go to the Moon and count the cigarette butts at one of the Apollo landing sites, you just don’t know if the astronauts were smoking on company time.

Krigging isn’t data. It’s just a guess.

In oil exploration, one might use Kriging to decide where the bore the next holes. However, if one counted the predictions of Kriging as active wells, one would be out of a job very quickly.

In climate science, Kriging is used to infill data where no actual records exist, and they ARE counted as “active wells.”

A total misuse of the procedure.

Kip:

Thank you so much for your work in sorting out the statistical issues with anomalies. You have a lot of patience.

As regards temperature accuracy, I would like note two problems of a physical chemistry nature: radiation field imbalance and water vapor.

In statistical mechanics “temperature” is a parameter that describes the amount of heat in some particular molecular mode. The temperature of a system can be known only when all modes are at equilibrium, that is 1)free to exchange energy between modes, and 2)free of exchange with external sources long enough to have stopped net heat flow.

For a sample of atmospheric gas we could define a “black body equivalent” (BBE) temperature that would represent the average molecular motion and radiation field density for the sample. In the real atmosphere the instantaneous value of radiation field density is far higher in the daytime, and far lower in the nightime than the BBE temperature. (It would be interesting to calculate how much energy is actually in the black body field.)

We finesse these complicated issues by sticking a thermometer in a wooden box and declaring that it is at equilibrium at the time of daily maximum and daily minimum and therefore a valid representation of the overall system. This method at least eliminates the effect of using different types of thermometers that interact differently with the radiation field. Yes, different thermometers will give different temperatures away from equilibrium, and painting the box black would change the reading and give higher daytime and lower nightime temperatures. It is difficult to assemble these ideas into a useful estimate of overall error of the BBE, but it looks as if the measurement error in temperature for assessment of equatorial heat is on the order of several degrees, not fractions of a degree.

But the worst violation of “temperature” as a measure of heat is not in thermal modes, but that overall something like a third of all heat incident on the planet surface gets turned into water vapor. As Pielke Sr. has shown, the real heat energy in an atmospheric sample can have effective temperature of tens of degrees different from the wood box temperature. This is why Key West has pretty much the same temperature all day, while Denver varies by 60 deg.F or more. It has no water to evaporate.

Temperature does drive temperature change, but it does not accurately represent atmospheric energy. Nick Stokes notwithstanding, enthalpy and its related heat equivalent temperature is the only measure that tells us if the energy content of the atmosphere is increasing or decreasing. Temperature alone however measured does not measure heat; it tells us in what direction the heat to which the thermometer is sensitive is flowing.

While I accept it as a statistic, I have yet to see a precise physical meaning for global temperature.

4kx3 ==> Ah yes, the larger issues. The work of Pielke Sr and others is generally ignored, as are the questions raised by Christopher Essex, Ross McKitrick, Bjarne Andresen (2006) in Does a Global Temperature Exist?

In comments here, we see Mosher saying he has personally invalidated the idea that T24 and Tmean are substantially different, despite recent published work showing precisely the opposite and supporting the final point of my essay. See Spatiotemporal Divergence of the Warming Hiatus over Land Based on Different Definitions of Mean Temperature, Chunlüe Zhou & Kaicun Wang Nature Scientific Reports | 6:31789 | DOI: 10.1038/srep31789.

Kip,

“recent published work showing precisely the opposite a”

It does not show precisely the opposite. It shows a plot of 10,400 stations from GHCN-D using T_24. And it shgows, beside, a plot of 3,400 stations from a different dataset, ISH, which used T_mean. There is no way to know whether differences are due to the method or to the fact of different datasets. They clearly aren’t the same places.

Kip: A note on the accuracy of temperature measures.

CO2 produces little change in heat capacity and no change in heat energy by itself. If we assert that changes in temperature are due to changes arising from CO2, it seems we must then be talking about effects on heat transfer, not temperature changes arising from chemical reactions or volcanoes.

Trenberth and Smith http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/abs/10.1175/JCLI-3299.1 provide estimates of the amount of water in the atmosphere. Water amounts to (1.8 +/- 1.1) /1000. of the total mass. Using the heat of vaporization of 2257 kj/kg and Cp of 1 kj/kgC suggests that globally the average error in using temperature and not enthalpy as a measure of heat is (4 +/- 2) degrees C. depending on season. Locally the error can easily be ten times this amount. While the “4” part of the error is systemic, some of the (+/- 2) part should show up in calculating the global average prior to “anomalizing”.

From the physical chemistry standpoint, discussions on the significance of various ways of calculating average (T2 or T24) are a waste of time until we define and assess exactly what subset of the various non equilibrium thermal modes we are estimating. While the max/min average method is crude, it is arguably less crude than taking some other time series with thermometers that are not properly equilibrated.

Nick Stokes ==> Read the whole study and the particularly the conclusion which speaks to the point I am making. Quantitative and trend differences — globally, regionally, and seasonally.

Kip,

“Read the whole study”

I have. The whole of it is affected by this basic fallacy. They measure T_mean with one set (ISH) and T_24 with the other (GHCN daily). There is no other relevant data. There is just no way there to separate the effect of T_2/T_24 from the GHCN/ISH difference.

Nick ==> I guess you’ll have to write to the journal and ask for a retraction….better than admitting my point is valid, huh?

Kip it seems you’re essentially telling folks that any average computed from measures of an abnormal distribution are at best misleading. There’s an assumption that averages come from normal distributions and that assumption may not be valid. It should be checked and there are simple ways to do that; methods that haven’t been used in the case of global mean temperature metrics?

I can understand and agree your critique of the 24 hour High/Low averages, but the anomaly metrics are intentionally meant to normalize poorly distributed data over longer time periods. Are you aware of any studies that demonstrate a normal or abnormal distribution in the longer term anomaly data sets?

Kip:

For clarity, I’m looking for anyone who’s presented a percentiles plot of the anomalies over the selected baseline period (population mean). If that plot shows an abnormality I’d be more likely to believe there was a force, other than natural variation, that was effecting global temperature. In the absence of an abnormality, I’d tend to think there was no other force involved and we are just observing natural variation.

Any references you might have would be appreciated.

Bartleby ==> The thrust of this series of three essays is to educate the general readership about the basics of averages and to warn them of the pitfalls that can trip up their understanding when they depend on averages to inform themselves.

“There’s an assumption that averages come from normal distributions and that assumption may not be valid.” Yes, this is one of the points I attempt to make: I say:

As for the climatology issue, using anomalies does not cure the problems of “using the wrong metric” (Tmean instead of T24 — see the Update at end of essay). Anomalies don’t cure using metrics that do not represent the physical thing or property they are subsequently claimed to represent.

Anomalies don’t handle the problems with Surface Air temperature raised by NOAA GISS .

I like Mosher’s bottom line on Global Average Temps quoted near the end of the essay:

I think there is a lot to learn and know about global climate….but these herculean attempts to reduce everything to Single Numbers and Global Averages are both misguided and misleading.

Kip writes: these herculean attempts to reduce everything to Single Numbers and Global Averages are both misguided and misleading.

Certainly you’ll get no argument for me on that.

“using anomalies does not cure the problems of “using the wrong metric” (Tmean instead of T24 — see the Update at end of essay).”