UPDATE: I finished writing this post and published it at my blog Climate Observations about the same time that Don Easterbrook’s post Cause of ‘the pause’ in global warming was published at WattsUpWithThat.

This post includes an overview of the mistakes people make when they attempt to use the Pacific Decadal Oscillation data as a metric for the dominant mode of variability in the Pacific Ocean. So it contradicts Easterbrook’s post. More detailed discussions of what the PDO data represents and what it doesn’t represent can be found in the posts here, here and here. If you for some reason would like to argue about it on this thread, please see my comments on the Easterbrook thread starting here.

# # #

The Nature article Climate Change: The Case of the Missing Heat by Jeff Tollefson has received a lot of attention at WattsUpWithThat and around the blogosphere. Much of Tollefson’s article was a simplified explanation of the findings of Trenberth and Fasullo (2013) An apparent hiatus in global warming? We’ve discussed that paper already. See the posts Trenberth and Fasullo Try to Keep the Fantasy Alive and More on Trenberth and Fasullo (2013) “An Apparent Hiatus in Global Warming?”

Anthony Watts was right to call attention to Tollefson’s article; it presented an argument and illustration that had been presented years ago by skeptics, an argument and illustration that had been dismissed by global warming enthusiasts. And Tollefson is linking it to Trenberth and Fasullo.

One point needs to be made right from the get go. As far as I could tell, no one interviewed for the Nature article claimed the hiatus in surface warming was not happening. That article is an attempt to explain the growing differences between the model simulations and measured global average surface temperatures. And the more I look at it, Tollefson appears a bit skeptical at times.

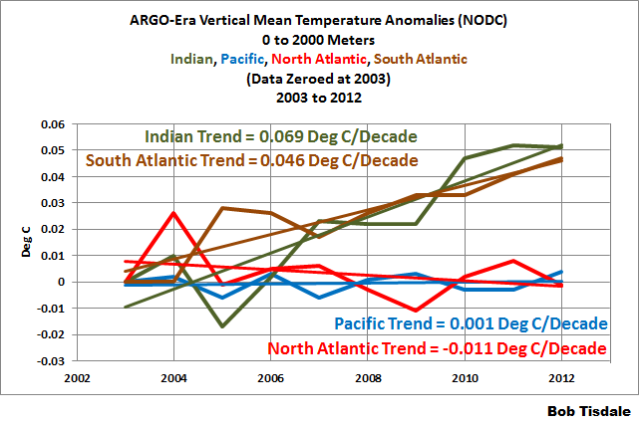

One problem with Tollefson’s article: it only discusses the hiatus in surface temperature warming. It does not address the absence of warming of the Pacific Ocean and North Atlantic to depths of 2000 meters, for the period of 2003 to 2012. See Figure 1. Only the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans show warming to depth. Figure 1 is from the post here.

Figure 1

Manmade greenhouse gases cannot select which ocean basins they decide to warm.

And the Tollefson article, unfortunately, offers as much misinformation as information.

The first problem, as noted above, was the article does not address the “missing heat” in the depths of the Pacific over the last decade, and that is where the heat would have to be appearing if Trenberth and Fasullo (2013) were correct.

The second problem has to do with using Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) data as a metric for the strength, frequency and duration of El Niño and La Niña events. It’s the wrong dataset.

El Niño and La Niña events are the primary focus of the article. Tollefson acknowledges this with his statement:

And here, the spotlight falls on the equatorial Pacific.

But then he presents Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) data as the metric for El Niños and La Niñas. He’s likely taking his cue from Trenberth and Fasullo (2013) for that.

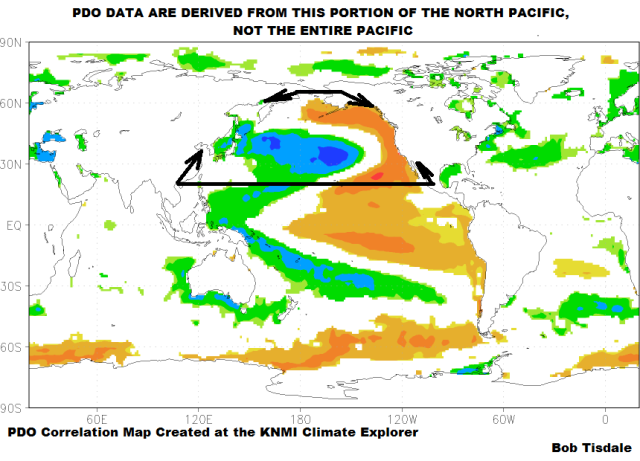

El Niño and La Niña events take place in the tropical Pacific, but the Pacific Decadal Oscillation dataset is an abstract form of sea surface temperature data derived from the extratropical North Pacific, not the tropical Pacific. See Figure 2.

Figure 2

The PDO data basically represent how closely the spatial pattern of the sea surface temperature anomalies of the North Pacific (north of 20N) resembles the pattern created by ENSO events (where the spatial patterns are warmer in the east and cooler in the central and western North Pacific during El Niños, and cooler in the east and warmer in the central and western North Pacific during La Niñas). Because that spatial pattern of sea surface temperatures in the North Pacific is also impacted by sea level pressures (and their interrelated wind patterns), the Pacific Decadal Oscillation data are not a true representation of the frequency, magnitude and duration of El Niño and La Niña events.

For more information about what the PDO represents, and more importantly what it doesn’t represent, see the posts here, here and here.

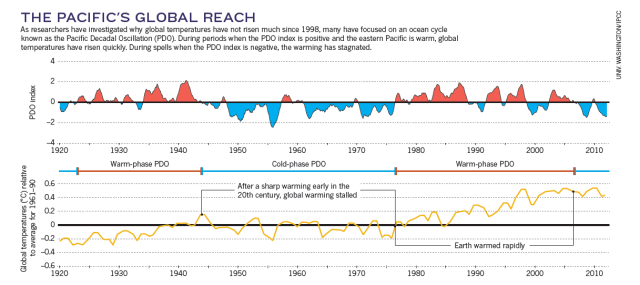

Figure 3

The big surprise in the Nature article was the illustration comparing the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) data with the global surface temperatures titled “The Pacific’s Global Reach”. I’ve included it as my Figure 3. It compares the JISAO PDO data to global surface temperature anomalies. The text in the illustration clearly states:

During periods when the PDO index is positive and the eastern Pacific is warm, global temperatures have risen quickly. During spells when the PDO index is negative, the warming has stagnated.

Additionally, with respect to the illustration, the article reads:

An analysis of historical data buttressed these conclusions, showing that the cool phase of the PDO coincided with a few decades of cooler temperatures after the Second World War (see ‘The Pacific’s global reach’), and that the warm phase lined up with the sharp spike seen in global temperatures between 1976 and 1998 (ref. 4).

This, of course, strongly suggests that the warm phase of the PDO is responsible for part of the warming during the period from 1976 to 1998. If the PDO can stop the warming, then the PDO had to have contributed to the warming. That had been a skeptical argument for years. I can recall seeing similar graphs more than 5 years ago. In fact, it was so popular SkepticalScience wrote a post about it here back in 2008.

Unfortunately, there are no mechanisms through which the PDO (as defined by the JISAO dataset) can cause global surface temperatures to vary. The sea surface temperatures of the North Pacific north of 20N are inversely related to the PDO data.

Those mechanisms exist in the tropical Pacific and portray themselves as El Niños and La Niñas. Sea surface temperature-based indices for the strength, frequency and duration of El Niños and La Niñas do exist. In fact, Trenberth and Stepaniak (2001) Indices of El Niño Evolution (online edition here) recommended using the sea surface temperature anomalies of the NINO3.4 region of the equatorial Pacific (identified as N3.4 in the paper). See the illustration here for the location of the NINO3.4 region. Trenberth and Stepaniak (2001) used the HADISST dataset, with the base years of 1950-1979 for anomalies. Unfortunately, Trenberth and Stepaniak never really provided a scientific justification for using the base years of 1950 to 1979. So we would be better off using the entire term of the data (1923 to 2013) as the base years for the NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies.

The NINO3.4 sea surface temperature data are realistic index for strength, frequency and duration of El Niño and La Niña events. So let’s look at the average NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies for the two warming periods and the two hiatus periods. See Figure 4. We’ll use the periods defined by Trenberth and Fasullo (2013):

The monthly time series (Figure 8) readily reveals the multidecadal regimes of the PDO (given by the black line) with positive phases from 1923 to 1942 and 1976 to 1998, and negative phases from 1943 to 1976 and after 1999.

Curiously, the periods presented by Trenberth and Fasullo (2013) do not agree with those presented by Tollefson in his “The Pacific’s Global Reach” illustration. That aside, my Figure 4 shows that during the two warming periods of 1923 to 1942 and 1976 to 1998, the average sea surface temperature anomalies for the NINO3.4 region were well above zero. This means that El Niño events dominated that period. Global surface temperatures should warm during those periods because the tropical Pacific is releasing more heat than “normal” from the tropical Pacific and redistributing more warm water than “normal” to adjacent ocean basins. And during the two hiatus periods of 1943 to 1976 and 1999 to present, the average NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies are below zero. That of course means the tropical Pacific is releasing less heat than “normal” and redistributing less warm water than “normal” to adjacent ocean basins. And during those periods global surface temperatures flattened or cooled slightly.

Figure 4

You may be asking yourself, why did Bob go through that exercise when it basically showed the same results as Tollefson’s PDO graph?

The NINO3.4 data are the correct dataset to use and the PDO is not. The PDO does not represent the timing, strength and duration of El Niño and La Niña events. It portrays an aftereffect of El Niño and La Niña events, combined with the influence of the sea level pressure of the North Pacific.

But now we have to consider that the NINO3.4 sea surface data only capture the effects of ENSO on a small region of the equatorial Pacific. They do not represent the processes of ENSO or their aftereffects. And in no way can NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies account for the warm water that is left over from strong El Niño events, which is redistributed to adjacent ocean basins in their wakes.

MORE MISINFORMATION

The article states (my boldface):

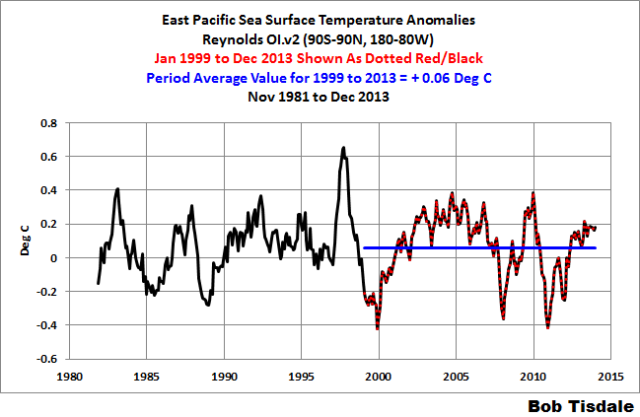

Just before the hiatus took hold, that region had turned unusually warm during the El Niño of 1997–98, which fuelled extreme weather across the planet, from floods in Chile and California to droughts and wildfires in Mexico and Indonesia. But it ended just as quickly as it had begun, and by late 1998 cold waters — a mark of El Niño’s sister effect, La Niña — had returned to the eastern equatorial Pacific with a vengeance. More importantly, the entire eastern Pacific flipped into a cool state that has continued more or less to this day.

Entire eastern Pacific? The PDO data do not represent the “entire eastern Pacific”. If he’s thinking sea surface temperature anomalies, that’s also wrong. There have been a number of El Niño events since 1999. Those El Niño events occurred in 2002/03…and 2004/05…and 2006/07…and 2009/10. As a result, the average sea surface temperature anomalies [of the East Pacific], using NOAA’s standard base years 1971-2000 for their Reynolds OI.v2 data, for the period of January 1999 to December 2013 are +0.06 deg C, and that’s a far cry from “a cool state that has continued more or less to this day.” See Figure 5.

Figure 5

MODEL NONSENSE

The article reads:

Second, many researchers have found the opposite pattern in simulations with full climate models, which factor in the suite of atmospheric and oceanic interactions beyond the equatorial Pacific. These tend to reveal a trend towards more El Niño-like conditions as a result of global warming.

Climate models don’t simulate ENSO properly, so this is irrelevant. See Guilyardi, et al. (2009) “Understanding El Niño in Ocean-Atmosphere General Circulation Models: Progress and Challenges” and Bellenger, et al. (2013): “ENSO Representation in Climate Models: From CMIP3 to CMIP5.” Preprint copy is here.

THINGS OVERLOOKED

The following was written for the post Comments on Stefan Rahmstorf’s Post at RealClimate “What ocean heating reveals about global warming”. The discussion applies here as well. I’ve changed the Figure numbers and made a few minor revisions for this post.

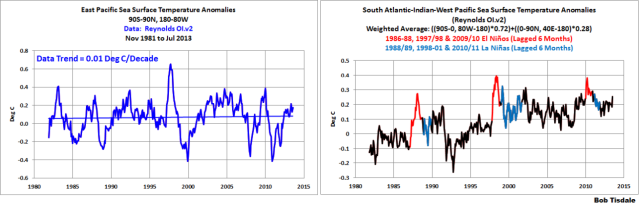

In the left-hand graph of Figure 6, we can see that the sea surface temperatures of the East Pacific have warmed little, if at all, over nearly the past 32 years…since the start of the Reynolds OI.v2 sea surface temperature dataset in November 1981. The East Pacific (90S-90N, 180-80W) covers about 33% of the surface of the global oceans. The papers presented by Jeff Tollefson do not address this lack of warming and climate models do not simulate it.

Figure 6

The same hold true for what’s illustrated in the right-hand graph, and they are the sea surface temperature anomalies of the South Atlantic, Indian and West Pacific oceans. The coordinates are listed in the title block. They cover more than 50% of the surface of the global oceans. We can see a number of things in the sea surface temperature data for the South Atlantic, Indian and West Pacific oceans: (1) their long-term warming depends on the El Niño events of 1986/87/88 and 1997/98 (and possibly the El Niño of 2009/10); (2) they do not cool proportionally during the transition to the trailing La Niñas of 1988/89 and 1998-01; but (3) they do cool slightly over the decade-long periods between the El Niño events of 1986/87/88 and 1997/98 and between the 1997/98 and 2009/10 El Niños.

For an introductory discussion of the natural warming of the global oceans refer to the illustrated essay “The Manmade Global Warming Challenge” (42MB).

The sea surface temperatures of the North Atlantic are governed by another mode of natural variability called the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation or AMO, which has been overlooked by Jeff Tollefson. The AMO is the reason why the sea surface temperatures there warmed at a much higher rate than the rest of the global oceans from the mid-1970s to the early-2000s. But the sea surface temperature data for the North Atlantic indicate the AMO may have already peaked. See Figure 7. If history repeats itself, and there is no reason to believe it will not, then the sea surface temperatures of the North Atlantic will show no warming and actually cool for a few more decades, assuming the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation has, in fact, peaked.

Figure 7

Note: For further information about the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, see NOAA’s AOML (Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory) Frequently Asked Questions webpage here, and my blog post here and my introduction to the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation here.

CLOSING

The article by Jeff Tollefson suggests the climate science community may be moving in the right direction—that’s a big MAY BE.

But they’ll have to return to basics: ENSO is fueled by sunlight. And for that reference, as I’ve presented numerous times before, we have Trenberth et al. (2002) Evolution of El Niño–Southern Oscillation and global atmospheric surface temperatures:

The negative feedback between SST and surface fluxes can be interpreted as showing the importance of the discharge of heat during El Niño events and of the recharge of heat during La Niña events. Relatively clear skies in the central and eastern tropical Pacific allow solar radiation to enter the ocean, apparently offsetting the below normal SSTs, but the heat is carried away by Ekman drift, ocean currents, and adjustments through ocean Rossby and Kelvin waves, and the heat is stored in the western Pacific tropics. This is not simply a rearrangement of the ocean heat, but also a restoration of heat in the ocean.

In other words, the stronger trade winds reduce cloud cover, which, in turn, allows more sunlight to warm the tropical Pacific. So, if the stronger trade winds are causing more warm water to be stacked up in the western tropical Pacific, it’s an increase in sunlight that’s fueling it. This was discussed in much more detail under the heading of DOWNWARD SHORTWAVE RADIATION VERSUS DOWNWARD LONGWAVE RADIATION DURING LA NIÑA EVENTS in the post Open Letter to the Royal Meteorological Society Regarding Dr. Trenberth’s Article “Has Global Warming Stalled?”

The perception, like the sun, might just be beginning to turn – well worth a view.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-25771510

Regards

Barry Wells

Thanks Bob. I have a feeling you’re pulling us closer to the truth.

This might sound trivial, but if you dive down 20 feet and stay there in a sea, say to scuba dive, it ain’t half cold without that wet suit. Sometimes you blind me with science, but I do know what I have personally experienced around the world, and sea temps do fluctuate. In Kyrenia in Cyprus, the harbor was much warmer than the sea outside. It was shallower of course. Is that trite. With tides especially Ebb tides, only on a full moon, the seas naturally rise higher onto the land.

Thanks for keeping it real Bob.

Has anyone do quantitative analysts. I have and quite honestly you only concentrate on one area, taken on a global scale it is near impossible.