Guest post by Bob Tisdale

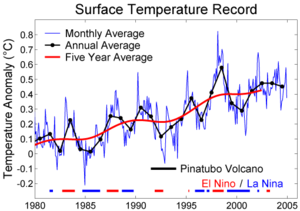

In this post, I divide the globe (60S-60N) into two subsets and remove the linear effects of ENSO and volcanic eruptions from GISS Land-Ocean Temperature Index data since 1982. This is done using common methods. I further adjust the data to account for secondary ENSO-related processes. The Sea Surface Temperature subsets used for these adjustments are identified. The processes are briefly discussed, supported by links to past posts, and the data are presented that support the existence of these secondary effects. An additional volcanic aerosol refinement that increases the global trend is made. The bottom line is, the GISS LOTI and Reynolds OI.v2 SST data indicates that natural variables could be responsible for approximately 85% of the rise in global surface temperature since 1982. I’ll be the first to point out that I qualified my last sentence with the word “could”. This post illustrates a story presented by the data, nothing more. But this basic evaluation indicates these secondary effects of ENSO require further research.

This post continues with the two-year series of posts that basically illustrate that the effects of El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cannot be accounted for using a single index like a commonly used SST-based dataset such as NINO3.4, or CTI, or MEI. These indices represent only the sea surface temperature of the central and eastern equatorial Pacific (that’s modified in the case of the MEI). They do not represent the process of ENSO. They do not account for the warm water that is returned to the western Pacific and redistributed during the La Niña. This post provides further evidence of those effects.

This post is long but I elected not to divide it in two. It’s 6,000 words or 13 single-spaced pages in length. It includes 32 Figures, a gif animation, and a video. So there’s a lot to digest. I tried to anticipate questions and answer them.

REMOVING THE LINEAR EFFECTS OF ENSO AND VOLCANIC AEROSOLS HELP TO SHOW THE TIMING OF THE WARMING

Many papers and blog posts that attempt to prove the existence of anthropogenic global warming remove the obvious linear effects of El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events and of stratospheric aerosols discharged by explosive volcanic eruptions. An example is Thompson et al (2009) “Identifying Signatures of Natural Climate Variability in Time Series of Global-Mean Surface Temperature: Methodology and Insights”… http://www.atmos.colostate.edu/ao/ThompsonPapers/ThompsonWallaceJonesKennedy_JClimate2009.pdf

…and its companion paper Fyfe et al (2010), “Comparing Variability and Trends in Observed and Modelled Global-Mean Surface Temperature.”

http://www.atmos.colostate.edu/ao/ThompsonPapers/FyfeGillettThompson_GRL2010.pdf

Let’s run through the process using GISS Land-Ocean Temperature (LOTI) data. That’s their global temperature anomaly dataset with the 1200km radius smoothing. A known problem with that dataset is that GISS Deletes Arctic And Southern Ocean Sea Surface Temperature (SST) Data. Since that creates a bias, we’ll delete the GISS LOTI data where they extend land surface data (with its higher variability) out over the oceans. That is, we’ll confine the data used in this post to 60S-60N.

Someone is bound to complain that I’ve deleted the Arctic data from the GISS LOTI data and that the Arctic is warming much faster than lower latitudes. Keep in mind that the Arctic is amplifying the effects of the rise in temperature at lower latitudes. This is the basis of the concept of polar amplification. If the vast majority of the change in temperature at the lower latitudes is natural, the same would hold true for the Arctic. Regardless, these latitudes were also chosen because the effects I want to illustrate with this post are relatively easy to display using them.

Back to the data: since GISS switches sources for their Sea Surface Temperature data from HADISST to Reynolds OI.v2 data in December 1981, we’ll look at the LOTI data starting in 1982. Smith and Reynolds (2004) Improved Extended Reconstruction of SST (1854-1997)] states the following about the OI.v2 SST data: “Although the NOAA OI analysis contains some noise due to its use of different data types and bias corrections for satellite data, it is dominated by satellite data and gives a good estimate of the truth.”

The truth is a nice place to start.

And we’ll smooth the monthly data with a 13-month running-average filter to lessen noise and season variations.

Figure 1 shows monthly GISS LOTI data (60S-60N), from March 1982 to November 2010, compared to NINO3.4 SST anomalies. The NINO3.4 data represent the Sea Surface Temperature of a region in the central equatorial Pacific bound by the coordinates of 5S-5N, 170W-120W. NINO3.4 SST anomalies are a commonly used proxy for the strength and frequency of El Niño and La Niña events, also known as ENSO. (And for those new to ENSO, refer to An Introduction To ENSO, AMO, and PDO – Part 1.) Note also that the NINO3.4 data has been scaled (multiplied by a factor of 0.16) so that the rises of the two datasets are about the same during the evolution of the 1997/98 El Niño. The NINO3.4 SST anomalies have also been shifted down 0.01 deg C and moved back in time by 3 months (lagged) to align the leading edges of the two datasets at that time. (The data in the graph starts in March 1982 because of the 3-month lag in the NINO3.4 data.) I chose the 1997/98 El Niño because that event wasn’t opposed by a volcanic eruption and it was large enough to overwhelm the background noise. As you can see, the wiggles of lesser El Niño events after 2000 don’t match as well.

http://i53.tinypic.com/deuxdz.jpg

http://i53.tinypic.com/deuxdz.jpg

Figure 1

Many of the large year-to-year changes in global temperatures are removed when we subtract the scaled NINO3.4 data from the GISS Global (60S-60N) LOTI data. Refer to the “olive drab” curve in Figure 2. Since the NINO3.4 data has a negative trend since 1982, we increase the trend in the GISS LOTI data by subtracting it. Also note how the ENSO-adjusted GISS LOTI data has “flattened” after 1998. Without the volcano-related dip and rebound starting in 1991, the period from 1988 to 1998 would also be relatively flat. It appears as though the ENSO-adjusted GISS LOTI rose in two steps since 1982. Let’s remove the cooling effects of the El Chichon and Mount Pinatubo eruptions to see if that holds true. We’ll use a GISS dataset that represents Stratospheric Aerosols. (ASCII data) Like the ENSO Proxy, we’ll scale the data and lag it. The estimated range of the impact of Mount Pinatubo on Global Temperatures varies from 0.2 to 0.5 deg C, depending on the study, so we’ll use approximately 0.35 deg C to account for its effect. Visually, that scaling appears right.

http://i51.tinypic.com/8vyd54.jpg

http://i51.tinypic.com/8vyd54.jpg

Figure 2

Figure 3 illustrates the GISS Land-Ocean Temperature Index (LOTI) anomaly data with the linear effects of ENSO events and the effects of large volcanic eruptions removed. Also illustrated is the linear trend. I’ve included the linear trend line to illustrate the effect the straight line has on the appearance of the data. The trend line gives the misleading impression that there has been a constant but noisy rise in global temperatures.

http://i55.tinypic.com/zur19i.jpg

http://i55.tinypic.com/zur19i.jpg

Figure 3

During the discussion of Figure 2, I noted that the data appeared to flatten after 1998. The upward steps in the data can be illustrated if we present the period average temperature anomalies for the three periods of 1982 to 1987, 1988 to 1997, and 1998 to 2010.

http://i55.tinypic.com/m96sly.jpg

http://i55.tinypic.com/m96sly.jpg

Figure 4

WHAT COINCIDES WITH THE UPWARD STEPS?

The timings of those upward steps coincide with the transitions from the large El Niño to La Niña events that took place in 1988 and 1998. This can be seen in Figure 5, which includes the adjusted GISS LOTI data. The other dataset is scaled NINO3.4 SST anomalies that have been inverted (multiplied by a negative number). Figure 5 is a gif animation, and in it, the NINO3.4 data shifts up and down. That was done to show how precisely the upward steps in the adjusted GISS data coincide with ENSO transitions. The adjusted GISS data trails the NINO3.4 data by a month or two. And the scales are correct for both upward steps.

http://i54.tinypic.com/2i8b02b.jpg

http://i54.tinypic.com/2i8b02b.jpg

Figure 5

But how can ENSO be impacting global temperature data if we’ve subtracted the scaled NINO3.4 anomaly data from the Global (60S-60N) GISS LOTI anomalies?

LA NIÑA EVENTS ARE NOT THE OPPOSITE OF EL NIÑO EVENTS

The assumption made when we removed the linear effects of ENSO (discussion of Figure 1) was that La Niña events were the opposite of El Niño events. But they are not. (This is the same incorrect assumption made by papers like Thompson et al 2009). This post is very long and to adequately describe how La Niña events are not the opposite of El Niño events would make it much longer. So it will be best to provide links to earlier detailed discussions on this topic.

Refer to:

More Detail On The Multiyear Aftereffects Of ENSO – Part 1 – El Nino Events Warm The Oceans

And:

More Detail On The Multiyear Aftereffects Of ENSO – Part 2 – La Nina Events Recharge The Heat Released By El Nino Events AND…During Major Traditional ENSO Events, Warm Water Is Redistributed Via Ocean Currents.

And:

I provide a relatively brief description in the following section.

WHY ENSO INDICES LIKE NINO3.4 SST ANOMALIES DO NOT ACCOUNT FOR THE PROCESS OF ENSO

ENSO is a process, and ENSO indices such as NINO3.4 SST anomalies, the Cold Tongue Index (CTI), or the Multivariate ENSO Index (MEI) do not account for that process.

El Niño description: A reduction in the strength of the Pacific trade winds triggers an El Niño. A number of interrelated events then take place. Huge amounts of warm water from the surface and, more importantly, from below the surface of the western tropical Pacific (the Pacific Warm Pool) slosh east during an El Niño and are spread across the surface of the central and eastern equatorial Pacific. The increased area of warm water on the surface allows the tropical Pacific Ocean to discharge more heat than normal into the atmosphere through evaporation. That, combined with the change in location of the convection, cause drastic changes in global atmospheric circulation patterns. As a result, global temperatures vary. And most parts of the globe outside of the central and eastern tropical Pacific warm during an El Niño. The changes in atmospheric circulation work their way eastward–over the Americas, the Atlantic, Europe and Africa, the Indian Ocean and Asia. Eventually, the changes reach the western Pacific, but by that time, the El Niño is transitioning to a La Niña.

Refer again to the NINO3.4 SST anomaly data in Figure 1. A La Niña event, based on the temperature values on a graph, appears to be an El Niño of the opposite sign, and for some regional responses in temperature and precipitation that is true. But as noted before the use of NINO3.4 SST anomalies or other ENSO indices does not capture the fact that ENSO is a process. Those indices fail to account for the relocation and redistribution of huge amounts of warm water.

In the description of the El Niño, I noted that huge amounts of warm water from the surface and below the surface of the West Pacific Warm Pool had sloshed east during an El Niño. What happens to all of that warm water from below the surface of the Pacific Warm Pool that had been spread across the surface of the central and eastern tropical Pacific during the El Niño? Before the El Niño, it was below the surface and not included in the measured global surface temperature anomalies. During the El Niño, some of the warm water that had been below the surface is now on the surface of the central and eastern tropical Pacific and included in the measured global temperature. In response, surface temperatures there rose. The ENSO index captures that part of the process and only that part.

But during the La Niña, what happens to the warm water? It wasn’t all “used up” by the El Niño. And what happens to all of the subsurface warm water that had shifted east during the El Niño and had remained below the surface. It doesn’t simply disappear during the La Niña. Answering those questions explains why La Niña events are not the opposite of El Niño events, and why an ENSO index does not capture the aftereffects of an ENSO event.

The leftover warm water returns to the western Pacific. This is accomplished in a few ways. One is through a phenomenon called a slow-moving Rossby Wave. This can be seen in Video 1. It illustrates global Sea Level Residuals from January 1998 to June 2001 and captures the 1998/99/00/01 La Niña in its entirety. The video was taken from the JPL video “tpglobal.mpeg”. The slow moving Rossby wave is shown as the westward moving band of elevated sea level at about 10N. Watch the effect it has on western Pacific Sea Level Residuals when it reaches there.

The second way that the leftover warm water is carried to the Western Pacific is through a strengthening of the trade winds. During a La Niña event, trade winds strengthen above their “normal” levels and the ocean currents carry the warm water back to the west and then poleward.

Animation 1 is taken from the videos in the post La Niña Is Not The Opposite Of El Niño – The Videos. It presents the 1997/98 El Niño followed by the 1998 through 2001 La Niña. Each map represents the average Sea Surface Temperature anomalies for a 12-month period and is followed by the next 12-month period in sequence. Using 12-month averages eliminates the seasonal and weather noise. The effect is similar to smoothing data in a time-series graph with a 12-month running-average filter.

There are a number of things to note in Animation 1. First, the El Niño and La Niña events cause changes in the sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific. The NINO3.4 SST anomalies used in this post are a measure of that variation in the central equatorial Pacific, and only that variation. Second, during the El Niño, note how the sea surface temperatures warm first in the Atlantic, then in the Indian Ocean, and then in the western Pacific. The warming is caused by changes in atmospheric circulation. And by the time these changes in atmospheric circulation make their way east to the western Pacific and it starts to warm there, the El Niño is transitioning to La Niña. Third, note how the sea surface temperature anomalies in the Western Pacific (and East Indian Ocean) continue to rise as the La Niña event strengthens. Fourth, note how the SST anomalies remain elevated in the East Indian and West Pacific Oceans during the entire term of the 1998/99/00/01 La Niña.

http://i53.tinypic.com/etb58j.jpg

Animation 1

The Sea Surface Temperatures of the East Indian and West Pacific Oceans remain elevated during the La Nina because the stronger trade winds reduce cloud cover. The reduction in cloud cover allows more Shortwave Radiation (visible light) to provide additional warming of the tropical Pacific waters east of the Pacific Warm Pool. The ocean currents carry this sunlight-warmed water to the west and then poleward.

DIVIDING THE GLOBE IN TWO HELPS IDENTIFY THE REASONS FOR THE UPWARD STEPS IN THE GISS LOTI DATA

To help illustrate the reasons for the upward shifts in the ENSO- and Volcano-adjusted GISS LOTI data (Figure 4), let’s divide the data into two subsets split at 20N. Refer to Figure 6.

http://i52.tinypic.com/jjpl5c.jpg

Figure 6

First we’ll look at the Northern Hemisphere GISS LOTI anomaly data, north of 20N. It has a relatively high linear trend since 1982, about 2.8 deg C/Century. Part is due to the additional variability of the North Atlantic. To compound that, these latitudes have a relatively high land surface area, and land surface temperatures vary much more than sea surface temperatures. The land surface area of the Northern Hemisphere latitudes of 20N-60N is about 45% of the total surface area, but the land surface in the tropical and Southern Hemisphere latitudes of 60S-20N is only 17%.

http://i53.tinypic.com/20mdjc.jpg

http://i53.tinypic.com/20mdjc.jpg

Figure 7

The dataset shown in Figure 7 has not been adjusted for ENSO or volcanic eruptions. Let’s correct first for ENSO, then for the volcanic eruptions, using the same methods we did for the Global (60S-60N) data. Figures 8 and 9 illustrate the interim steps and the required scaling factors, and Figure 10 illustrates the result.

http://i53.tinypic.com/15odzkh.jpg

http://i53.tinypic.com/15odzkh.jpg

Figure 8

http://i52.tinypic.com/34jdp94.jpg

http://i52.tinypic.com/34jdp94.jpg

Figure 9

http://i55.tinypic.com/vmx18x.jpg

http://i55.tinypic.com/vmx18x.jpg

Figure 10

The Northern Hemisphere data still has a relatively high trend, approximately 2.2 deg C/Century. But what causes the additional variability if we’ve removed the effects of ENSO and volcanic eruptions? The additional variations are often described as noise, but they have sources.

THE KUROSHIO-OYASHIO EXTENSION HOLDS THE ANSWER

There is a strong ENSO-related warming of the Kuroshio-Oyashio Extension that occurs during La Niña events. This was discussed and illustrated in my recent post The ENSO-Related Variations In Kuroshio-Oyashio Extension (KOE) SST Anomalies And Their Impact On Northern Hemisphere Temperatures. That secondary warming can be used to explain a major portion of the year-to-year variability in Northern Hemisphere land and sea surface temperature. And, along with ENSO, it helps to explain nearly all of the variations in the Northern Hemisphere (20N-60N) GISS LOTI data, including the rising trend. Figure 11 illustrates the location of the KOE dataset used in this post (30N-45N, 150E-150W).

http://i52.tinypic.com/14twvox.jpg

Figure 11

The GISS LOTI anomalies for much of the Northern Hemisphere warm (cool) when the Kuroshio-Oyashio Extension SST anomalies warm (cool). This can be seen in the correlation map of annual (January to December) Kuroshio-Oyashio Extension SST anomalies and annual Northern Hemisphere (0-90N) GISS LOTI data, Figure 12. Also note the correlation with the North Atlantic.

http://i54.tinypic.com/303llxg.jpg

Figure 12

As mentioned above, the secondary warming of the Kuroshio-Oyashio Extension was discussed in detail in my recent post The ENSO-Related Variations In Kuroshio-Oyashio Extension (KOE) SST Anomalies And Their Impact On Northern Hemisphere Temperatures. A quick description of the process: During a La Niña event, leftover warm water from the El Niño is returned to the Western Pacific and spun poleward by the North and South Pacific gyres. Much of that warm water finds its way to the Kuroshio-Oyashio Extension, where it apparently impacts atmospheric circulation.

The agreement between the variations in KOE SST anomalies and the adjusted Northern Hemisphere GISS LOTI anomalies is shown in Figure 13. I find that match quite remarkable. The additional spike (highlighted in blue) in the KOE data that starts in 1990 is out of place. It will make itself known later in this post. The other thing to note is the scaling factor required to align the two datasets in Figure 13. The scaling factor of 0.7 is very high. We’ll discuss this later in the post.

http://i51.tinypic.com/2j15udv.jpg

http://i51.tinypic.com/2j15udv.jpg

Figure 13

Some might think the agreement between those datasets is a lucky coincidence. Of course, the agreement between the adjusted LOTI data and the unadjusted KOE data in Figure 13 is based solely on the lags and scaling factors I used. But the scaling and lags were established logically. Eyeballing the data, the scaling factors appear to be correct. And as we shall see, using the same methods, the results are very similar for the data that covers the Tropics and Southern Hemisphere.

LET’S LOOK AT THE TROPICS AND SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE

The Southern Hemisphere and Tropics dataset includes the GISS LOTI data from 60S-20N, Figure 14. This subset has a relatively low trend, approximately 1 deg C/Century. Some of this is related to the amount of continental land mass. For these latitudes, land represents only about 17% of the surface area. The Southern Ocean (90S-60S), which is outside of the latitudes portrayed in the post, also impacts the Southern Hemisphere data. And since the Southern Ocean SST anomaly trend over this period is negative, its interaction with the Southern Hemisphere oceans lowers the trend of the dataset.

http://i54.tinypic.com/eiqtsy.jpg

http://i54.tinypic.com/eiqtsy.jpg

Figure 14

And again, using the same methods, we’ll adjust for ENSO, then volcanic eruptions, Figures 15 and 16, and present the results, Figure 17. Refer to Figures 15 and 16 for the scaling factors.

http://i56.tinypic.com/e5nxg1.jpg

http://i56.tinypic.com/e5nxg1.jpg

Figure 15

http://i56.tinypic.com/2vx28tt.jpg

http://i56.tinypic.com/2vx28tt.jpg

Figure 16

http://i53.tinypic.com/2cqy0s3.jpg

http://i53.tinypic.com/2cqy0s3.jpg

Figure 17

As shown in Figure 17, removing the effects of the volcanoes has once again lowered the trend, and removing the ENSO data reduced the year-to-year variations.

Now we need a dataset for these latitudes to illustrate the secondary warming due to the leftover warm water from El Niño events and use it to account for the adjusted GISS LOTI data for the latitudes of 60S-20N.

THE SOUTH PACFIC CONVERGENCE ZONE (SPCZ) EXTENSION SST ANOMALY DATA AND CORRELATION MAP ARE REVEALING

The KOE was used in the discussion of the Northern Hemisphere data, so it seems logical that a similar area exists in the South Pacific. And for this discussion, we’ll designate that area as the South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ) Extension. The SPCZ Extension data will be the SST anomalies of the area east of Australia (35S-20S, 160E-150W). As shown in Figure 18, it had a relatively high SST anomaly at the peak of the 1998/99 portion of the 1998 through 2001 La Niña.

http://i56.tinypic.com/2zhpb92.jpg

Figure 18

The SST anomalies for SPCZ Extension are shown in Figure 19.

http://i51.tinypic.com/2dinmgw.jpg

http://i51.tinypic.com/2dinmgw.jpg

Figure 19

Like the KOE Extension data, the SST anomalies of the SPCZ Extension warm greatly during transitions from El Niño to La Niña events and appear to shift upward at those times. Refer to Figure 20.

http://i54.tinypic.com/35mf4v8.jpg

http://i54.tinypic.com/35mf4v8.jpg

Figure 20

Creating the correlation map of annual (January to December) SPCZ Extension SST anomalies and annual Tropical and Southern Hemisphere (90S-20N) GISS LOTI data was eye-opening. It appears the SPCZ data is a good proxy for those areas in the western tropical Pacific and southwest Pacific that warm during La Niña events. It would also appear to show the effects those western Pacific areas have on the rest of the globe. As we can see in Figure 21, when the SPCZ Extension warms (cools) many areas throughout the tropics and Southern Hemisphere warm (cool). But as illustrated in Figure 20, the warming that occurs during La Niña events is not counteracted by the cooling during El Niño events. This causes the data to rise in steps during the La Niña events.

http://i56.tinypic.com/30d9xt0.jpg

Figure 21

Does the correlation map indicate that the upward shifts in the SPCZ Extension data also exist in the tropical and Southern Hemisphere GISS LOTI data? My understanding of correlation maps is that they emphasize the larger events in the data, and if we refer again to Figure 20, the larger events are those that occur during these upward shifts. We can also confirm this by comparing the respective time-series graphs.

Figure 22 illustrates the adjusted GISS LOTI data for the Tropics and Southern Hemisphere north of 60S. Also shown are scaled (0.25) SPCZ Extension SST anomalies. There are minor divergences from time to time, but in general the two curves agree surprisingly well.

http://i53.tinypic.com/6tmj9y.jpg

http://i53.tinypic.com/6tmj9y.jpg

Figure 22

WHAT’S THE BOTTOM LINE?

What do the curves and linear trends of the adjusted GISS LOTI data look like if the KOE and SPCZ Extension data are removed? And what happens when you combine the two results to form a global dataset with all of the adjustments? Let’s take a look. The Northern Hemisphere GISS LOTI data (20N-60N) that’s been adjusted for ENSO and volcanic aerosols and the KOE SST anomalies is shown in Figure 23. Recall the divergence circled in blue in Figure 13; that’s the cause of the significant additional dip in 1990. Other than that, this was not a bad first attempt with scaling factors. But notice how small the trend is, 0.13 deg C/Century. If that dip was removed, the trend would be even lower.

http://i51.tinypic.com/jze2o9.jpg

http://i51.tinypic.com/jze2o9.jpg

Figure 23

The Tropical and Southern Hemisphere GISS LOTI data (60S-20N) with the ENSO, Volcano, and SPCZ Extension adjustments is shown in Figure 24. The trend is basically flat. This dataset appears noisy, but look at the temperature scale. The range is only one-quarter of one used in Figure 23.

http://i53.tinypic.com/67i7iu.jpg

http://i53.tinypic.com/67i7iu.jpg

Figure 24

We can combine the Northern Hemisphere data (20N-60N) with the Tropical and Southern Hemisphere data (60S-20N) using a weighted average. (The latitudes of 20N-60N represent approximately 29% of the surface area between 60S-60N.) Figure 25 shows the result. The linear trend is basically flat at 0.06 deg C/Century. The saw-tooth pattern is interesting, but…

http://i53.tinypic.com/29cw9dc.jpg

http://i53.tinypic.com/29cw9dc.jpg

Figure 25

Due to the timing, the saw-tooth pattern appears to indicate that there was a lagged (repeated) volcano signal in the data. Refer to Figure 26. The reason I say repeated is that originally when the volcanic signal was removed, the Aerosol Optical Depth data was lagged 3 months and the leading edges of the data aligned well in Figures 9 and 16. The volcano signals in Figures 25 and 26, assuming those spikes are volcano signals, are lagged 9 months. The additional signal may also simply mean the Sato Mean Optical Thickness data doesn’t account perfectly for the decay of the volcano signal and that an additional adjustment is required.

http://i51.tinypic.com/6rjxpg.jpg

http://i51.tinypic.com/6rjxpg.jpg

Figure 26

So let’s make the secondary volcano correction, refer to Figure 27. That will raise the linear trend of the adjusted GISS LOTI data.

http://i54.tinypic.com/2a8s204.jpg

http://i54.tinypic.com/2a8s204.jpg

Figure 27

After all of the adjustments are made, there is a small trend, about 0.24 deg C/Century. Compared to the original, unadjusted data, Figure 28, the trend of the adjusted data is only about 15% of the original GISS LOTI data for 60S-60N.

http://i56.tinypic.com/wnxa9.jpg

http://i56.tinypic.com/wnxa9.jpg

Figure 28

This makes perfect sense since there is little to no evidence of an anthropogenic global warming effect on global Ocean Heat Content (OHC) data. All one needs to do is divide the global oceans into tropical and extratropical subsets per ocean basin. Then it’s relatively easy to determine that ENSO, changes in Sea Level Pressure, and AMO/AMOC are responsible for that vast majority of the rise in OHC since 1955. Refer to:

A. ENSO Dominates NODC Ocean Heat Content (0-700 Meters) Data

B. North Pacific Ocean Heat Content Shift In The Late 1980s

C. North Atlantic Ocean Heat Content (0-700 Meters) Is Governed By Natural Variables

SHOULDN’T THE KUROSHIO-OYASHIO EXTENSION AND SPCZ EXTENSION DATA BE DETRENDED?

In this post and in The ENSO-Related Variations In Kuroshio-Oyashio Extension (KOE) SST Anomalies And Their Impact On Northern Hemisphere Temperatures, we illustrated that the Kuroshio-Oyashio Extension and South Pacific Convergence Zone Extension SST anomalies rise in steps during La Niña events. Since those upward steps are clearly responses to ENSO, there should be no need to detrend those datasets.

A NOTE ABOUT THE ATLANTIC MULTIDECADAL OSCILLATION

There is a natural variable I did not account for in this post, and it is the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, or AMO. I did not remove its impacts on the Northern Hemisphere data. For those new to the AMO, refer to An Introduction To ENSO, AMO, and PDO — Part 2.

As noted in that post, RealClimate defines the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (“AMO”) as, “A multidecadal (50-80 year timescale) pattern of North Atlantic ocean-atmosphere variability whose existence has been argued for based on statistical analyses of observational and proxy climate data, and coupled Atmosphere-Ocean General Circulation Model (“AOGCM”) simulations. This pattern is believed to describe some of the observed early 20th century (1920s-1930s) high-latitude Northern Hemisphere warming and some, but not all, of the high-latitude warming observed in the late 20th century. The term was introduced in a summary by Kerr (2000) of a study by Delworth and Mann (2000).”

I could have accounted for the AMO before removing the impacts of ENSO and the volcanic eruptions. But I chose to leave it in so that I could include the impact of the KOE on the North Atlantic.

As shown in Figure 29, the trend of the North Atlantic SST anomalies between 20N-60N is 70% higher than the North Pacific SST anomalies trend. By accounting for that additional “some, but not all” trend from the AMO, the scaling factor required to align the KOE dataset with the North Hemisphere data would drop.

http://i52.tinypic.com/x4lx5t.jpg

http://i52.tinypic.com/x4lx5t.jpg

Figure 29

THE KOE SCALING IS TOO HIGH

The scaling factor for the Kuroshio-Oyashio Extension data in Figure 13 was 0.7. To some, it would not seem likely that the secondary warming of the KOE could raise temperatures for the Northern Hemisphere (20N-60N) that high, especially when one considers the multiplier for the SPCZ Extension was 0.25 in Figure 22.

First: Let’s consider the known effects of an El Niño event. When surface temperatures around the globe warm in response to an El Niño, most of those areas warm due to changes in atmospheric circulation. That is, they do not rise because the heat released into the atmosphere is warming the land and sea surfaces. The following is an example I often use. During an El Niño, the tropical North Atlantic warms even though it is separated from the Pacific by the Americas. The tropical North Atlantic warms during the El Niño because the El Niño causes a weakening of the North Atlantic trade winds. With the decrease in Atlantic trade wind strength there is less evaporation, and if there is less evaporation, sea surface temperatures rise. There is also less upwelling of cool water from below the surface when the trade winds weaken. This also causes sea surface temperatures to rise.

Therefore, it is through teleconnections or atmospheric bridges, not the direct transfer of heat, that the KOE would impact the areas of the Northern Hemisphere.

Second: There is a second western boundary current extension in the Northern Hemisphere, and it is the Gulf Stream Extension in the North Atlantic. For this quick discussion, we’ll define the Gulf Stream Extension by the coordinates of 35N-45N, 75W-30W. The map in Figure 30 is a correlation map and it shows that when the Gulf Stream Extension warms (cools) there are many parts of the Northern Hemisphere that warm (cool). And note that the eastern tropical Pacific is negatively correlated, indicating that these areas warm during La Niña events.

http://i52.tinypic.com/x1alur.jpg

http://i52.tinypic.com/x1alur.jpg

Figure 30

Scroll back up to Animation 1. It also shows the parallel warming of the Gulf Stream Extension with the KOE.

But do the SST anomalies of the Gulf Stream Extension cool during El Niño events? As shown in Figure 31, the SST anomaly variations of the Gulf Stream Extension and the Kuroshio-Oyashio Extension are very similar. Both datasets can warm significantly during La Niña events but they do not drop proportionally during El Niño events. In an earlier linked post, I described the process that causes the KOE to warm, but I have not found a paper that describes the warming of the Gulf Stream Extension at those times. Why does the Gulf Stream Extension respond differently to El Niño and La Niña events? Like the KOE, is the warm water created during an El Niño also carried north by the Gulf Stream during the following La Niña? Do the changes in atmospheric circulation caused by the La Niña add to the warming? During the La Niña, does an increase in the strength of the North Atlantic trade winds also reduce cloud cover over the tropical North Atlantic? Does the warm water created by the decrease in cloud cover and resulting increase in sunlight then get transported to the Gulf Stream Extension? There are too many unanswered questions for me to use the Gulf Stream Extension data in this post.

http://i52.tinypic.com/4g6i9w.jpg

http://i52.tinypic.com/4g6i9w.jpg

Figure 31

But, the parallel warming of the KOE and the Gulf Stream Extension during the transitions from El Niño to La Niña events would help to reduce the KOE scaling factor required to explain the step changes in the adjusted GISS LOTI data.

WHAT ABOUT SOLAR?

If we scale sunspot numbers so that the variations from solar minimum to maximum represent about a 0.1 deg change in temperature, and if we lag the sunspot data 6 years, it compares well visually with the adjusted GISS LOTI data. Refer to Figure 32. Someone with additional data processing tools could duplicate the steps taken in this post and confirm how well the two curves align.

http://i51.tinypic.com/23jsjo1.jpg

http://i51.tinypic.com/23jsjo1.jpg

Figure 32

WHAT FUELS THE EL NIÑO EVENTS?

The warm water created during the previous La Niña(s) via the increase in Downward Shortwave Radiation (visible light) fuels El Niño events. This was discussed in More Detail On The Multiyear Aftereffects Of ENSO – Part 2 – La Nina Events Recharge The Heat Released By El Nino Events AND… …During Major Traditional ENSO Events, Warm Water Is Redistributed Via Ocean Currents.

CAN THE THIS TYPE OF EVALUATION BE EXTENDED BACK IN TIME?

I would not expect that what was presented in this post could be extended back in time. The Pacific climate shifted in 1976/77. In the abstract of Trenberth et al (2002), they write, “The 1976/1977 climate shift and the effects of two major volcanic eruptions in the past 2 decades are reflected in different evolution of ENSO events. At the surface, for 1979–1998 the warming in the central equatorial Pacific develops from the west and progresses eastward, while for 1950–1978 the anomalous warming begins along the coast of South America and spreads westward. The eastern Pacific south of the equator warms 4–8 months later for 1979–1998 but cools from 1950 to 1978.”

The way ENSO events interacted with the Kuroshio-Oyashsio Extension and the SPCZ Extension also appear different before and after 1979 in the correlation and regression analyses presented in that paper. Link to Trenberth et al (2002):

http://www.cgd.ucar.edu/cas/papers/2000JD000298.pdf

SOURCES

Most of the data used in this post are available through the KNMI Climate Explorer Monthly observations webpage. GISS LOTI is identified there in the second field under “Temperature” as “1880-now anomalies: GISS”, with the “1200km” radius smoothing. The Reynolds OI.v2 is listed under SST as “1982-now: 1° Reynolds OI v2 SST”. The coordinates used are identified in the text and/or on the graphs.

And if you want to attempt to duplicate my results but have never used the KNMI Climate Explorer, refer to the post Very Basic Introduction To The KNMI Climate Explorer for a place to start.

The dataset used to simulate the impacts of the volcanic eruptions is available through GISS:

http://data.giss.nasa.gov/modelforce/strataer/tau_line.txt

The Sunspot data is available through the KNMI Climate Explorer Monthly climate indices webpage. Refer to the Sunspots (1749-now, SIDC) field under the heading of “Sun”.

CLOSING REMARKS

This was a very basic attempt to approximate the effects of natural variables on global temperatures, using scaling and lags that were eye-balled. Sometimes basic things work well, and in this case, they appear to have done that. The similarities between the adjusted GISS LOTI datasets and the respective KOE and SPCZ Extension data were remarkable. While those similarities and the correlation maps do not prove the KOE and SPCZ Extension SST anomalies cause those addition rises in surface temperature, they imply that natural factors are causing the upward steps in global temperatures illustrated in Figure 4.

After some preliminary discussions, I divided the global (60S-60N) GISS LOTI data into two sections. The linear impacts of ENSO and volcanic eruptions were then removed from those subsets. The processes that cause the Sea Surface Temperatures in two parts of the Pacific to warm greatly during La Niña events were discussed. The unadjusted SST anomalies of the KOE and the SPCZ Extension were then compared to their respective adjusted GISS LOTI anomalies. The related curves were surprisingly similar. After removing the impacts of the KOE and the SPCZ Extension from the related GISS LOTI data, the linear trends dropped significantly. When the two GISS LOTI datasets were again combined, we had removed approximately 85% of what some consider to be the “anthropogenic global warming signal.”

This post differs from studies such as Thompson et al (2009). Thompson et al assumed that the ENSO proxy accounts for all of the processes within the Pacific that take place during ENSO events. In reality, NINO3.4 SST anomalies (or the CTI SST anomalies they used) can only account for the linear responses to the changes in equatorial Pacific SST anomalies. NINO3.4 SST anomalies cannot be assumed to account for the ENSO processes that take place within the Pacific or the aftereffects of those processes. What I presented in this post was a simple way to view those aftereffects within the Pacific and the global responses to them.

In short, I presented a story told by the GISS Land-Ocean Temperature Index and Reynolds OI.v2 SST data between the latitudes of 60S to 60N.

Discover more from Watts Up With That?

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Bill Illis: Thanks

eadler said:

“http://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2006/09/why-greenhouse-gases-heat-the-ocean/

Your explanation left out this important mechanism, so your conclusion that DLR cannot affect ocean heat is wrong.”

My explanation set out the flaw in that very proposition. Where do they account for the evaporative cooling in the interacting layer that cancels out the heating in the skin layer so as to prevent any reduction of the natural upward energy fllux ?

You cannot consider a water/air interface without dealing with evaporative cooling.

eadler Reur January 11, 2011 at 10:45 am

Your comments seem to hinge on a 2006 commentary piece at RealClimate, which I doubt would have passed peer review. But anyhow, let’s look at it using some engineering style first principles:

A] It all seems a tad futile in that even IF the methodology were correct, it alleges only a 0.08C rise for 2xCO2, (sensitivity), relative to pre-industrial, which, is hardly alarming. However, the experiment is apparently flawed, based on the parameters that have (not) been described etc. Furthermore, this result can only be determined during daylight hours, and the laws of physics do not stop at night.

B] Great accuracy is claimed for temperature measurements, but not for the instrument measuring downward LWR. More seriously, there was a dependence on an S-B calculation of up-welling radiation based on the surface temperature measurement, in order to determine the net radiation.** However the sea surface is far from constant, particularly when observed from a close distance on the vessel. By rights, there should be a separate value determined for emissivity for each data point, but it seems most unlikely that that could be done.

C] The skin temperature is not purely a radiative consideration because it is also affected strongly by evaporation and thermals. That’s using Trenberth & Fasullo (T & F) terminology. In their latest “Earth’s Energy Budget Diagram” they attribute ~60% of the global surface cooling to these drivers. OH, and they think ~10% of the calculated up-welling radiation escapes directly to space BTW. See B] (Oh, and 0.9 W/m^2 have gone missing)

D] The discussion on a skin layer up to 1mm deep seems to be rather speculative and irrelevant. The true skin wherein LWR is fully absorbed is a nano portion of any such 1 mm, (varying with wavelength a la Planck), and it is from there that re-emission occurs with great rapidity. That is also where the conductive interface and the evaporative molecules are located relative to the atmosphere. The statement that water up to 1 mm deep is in contact with the atmosphere, and consideration of its temperature gradient etc, is erh inappropriate.

E] There are many parameters that appear to have no consideration, for instance.

* Humidity variation would significantly alter the ratio of contribution of CO2 to the total GHG effect.

* Cloud cover increase generally increases humidity. (This may well explain the upward slope obtained in the graph, with increasing cloud cover).

* Humidity, wind speed and atmospheric pressure affects evaporation rate

* Wave action affects emission, mixing, & evaporation

* Wind speed affects the effectiveness of the conductive interface

F] My word, that’s a funny chart! Why doesn’t he simply show a legend for each data point? If I understand it they only took data between about 9:0 am and 10:00 pm. (eyeballed) So, what were the energy and temperature gradient considerations etc in those missing ~11 Hrs?. If I understand it correctly, at ~10:00 pm the flux varied between about -85 & -10 W/m^2. Is that right?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

** BTW eadler, you wrote to Matt G that 324 w/m^2 of back radiation (T & F say 333), heats the surface. Wrong! It slows down the escape of heat. In the case of T & F’s scenario, there is a net EMR transport of HEAT upwards of (396-333) = 63, not a downward gain of 300+ W/m^2 of HEAT. But don’t worry, Peter Minnett (RSMAS) got it wrong in his title too.

Also, in your citing of the 2006 Minnett piece there was reference to an article by Fred Singer which makes perfectly valid points that are not addressed in that RC expose.

See also: Stephen Wilde says: January 12, 2011 at 10:08 am

Stephen, sorry to cross yours, but mine was in draft late yesterday.

Bob Tisdale says:

“I’ve shown that natural variables could account for 85% of the warming since 1982. Does it? Dunno. It might be more; it might be less. But this interpretation of the data illustrates that AGW might not be as strong a signal as many propose.”

Thanks for that explanation. The extremists want to blame everything on CO2. But the more we learn, the more we understand that GHG’s are only a small part of any warming. Most of it is natural.

Bob, Figure 2 here succinctly reinforces one of your points:

Trenberth, K.E. & Stepaniak, D.P. (2001). Indices of El Nino Evolution. Journal of Climate 14, 1697-1701.

http://www.cgd.ucar.edu/cas/Trenberth/trenberth.papers/tniJC.pdf

Too bad that wasn’t presented in color.

We’ve got to be careful interpreting that plot though. They only looked at one extent (i.e. sliding-window width).

Also, due to the nonlinearites, we need to realize the distortion of a comparative look at the 2 time intervals studied in the paper’s various correlation maps – (relates to a point I made above when discussing North Atlantic SST). As the plots are structured, apples & oranges are being compared — still gives some info, but info that needs to be interpreted carefully – and which can be seriously misleading.

Bottom Line: Without varying extent, there’s a limit to what can be learned – and interpretations can run seriously afoul with so many blind spots (which are guaranteed if only one extent is studied).

The authors do succeed in getting people thinking in the right direction; even if a single paper can’t be all luxurious things desirable, it can be ruthlessly efficient in its succinctness.

eadler,

Some time back, I copied something rather simplistic that you wrote:

The part you are missing is that in the Arctic, the loss of summer sea ice, results in a strong reduction in reflection of the sunlight, and absorption by the open ocean. This is where the amplification comes in.

And now, I’ve finally got around to commenting.

For a start, you might like to examine the implications of this from NASA. Please study it carefully

Definition [albedo]

A ratio of the radiation reflected by a surface to that incident on it.

Clouds are the chief cause of variations in the Earth’s albedo since clouds have highly varying albedo, dependent upon thickness and composition. Old snow is about 55% (0.55), new snow around 80% (0.8). water surfaces vary from very low about 5% (0.05) at high sun elevation to at least 70%(0.70) at low sun angles.

http://disc.sci.gsfc.nasa.gov/data-holdings/PIP/albedo.shtml

Sea-ice area changes, normally with old snow atop, also have some other complicated effects that you and your alarmist friends may have overlooked, but let‘s see how you go with the above for a start.

Paul Vaughan: Thanks for the link. I’ve enjoyed and learned much from Trenberth’s early papers. And yes, I did qualify that with “early”. His more recent work? Not so educational.

Thanks, Anthony.

Bob Tisdale wrote, “I’ve enjoyed and learned much from Trenberth’s early papers. And yes, I did qualify that with “early”. His more recent work? Not so educational.”

I found one of his 2010 papers useful. Clarification: My approach to filtering Trenberth’s communications is the same one I apply to Corbyn’s or anyone else’s: Mine for the substantive bits and filter off hyperpartisan nonsense.

–

I will reiterate Bob’s thanks to Anthony (& WUWT more generally).

Bob: You are wrong about volcanic cooling being documented for decades. These people had no idea what they were documenting because the presence of ENSO oscillations in global temperature curves was simply not understood. You will find an explanation and appropriate graphics in the second edition of my book, due out in a couple of weeks if not sooner. But let me give you a short explanation now. First you have to understand that ENSO oscillations – an alternation of warm El Nino and cool La Nina periods every four-five years – is present in all temperature curves. They normally comprise a temperature swing of approximately half a degree from El Nino peak to adjacent La Nina valley. They are well developed in the eighties and nineties and I have several graphics in that book that show this. The important figure to look at is Figure 9 because I use it to explain the difference between Pinatubo and El Chichon eruptions. It’s base is a satellite temperature graph that is is outlined in red. There are five El Nino peaks on the left side with La Nina valleys in between them. Self et al. whose article is in the big Pinatubo book “Fire and Mud” unhesitatingly assign the 1992/93 La Nina valley to Pinatubo cooling . Not only that, but they give it power over El Nino by pontificating that “Pinatubo climate forcing was stronger than the opposite warming effects of either the El Nino event or anthropogenic greenhouse gases in the period 1991-93.” For most people that would be case closed. But they also start to wonder why surface cooling is “…clearly documented after some eruptions (for example, Gunung Agung, Bali, in 1963) but not others – for example, El Chichon, Mexico, in 1982…” Well, I had to see what that meant. And as soon as I plotted the two that fit on the satellite graph I understood the reason: Pinatubo eruption coincides with the peak of an El Nino that is immediately followed by descent into a La Nina valley while El Chichon coincides with the bottom of a La Nina valley that is followed immediately by a steep climb to an El Nino peak. Just bad luck, no mystery about it. If a volcano erupts near the top of an El Nino peak it can claim the La Nina valley that follows for its own. But if it erupts at the bottom of a La Nina valley there is simply no way to do it and its cooling goes missing. If it were true that a volcano can override an El Nino warming then El Chichon would have been ideally situated to do that. But clearly it was a complete failure at that. I went on to test that with five other volcanoes and came to the conclusion that all so-called “volcanic cooling“ is nothing more than a misinterpretation of La Ninas that belong to ENSO. And the variability of warming is caused by the different degrees of overlap between volcanic and ENSO phases. Obviously some textbooks need to be rewritten but this is their problem for accepting shoddy ideas in the first place.