Guest Post by Willis Eschenbach

In my last post, which was about the Mauna Loa Observatory (MLO) in Hawaii, Dr. Richard Keen and others noted that for a good comparison, there was a need to remove the variations due to El Nino. Dr. Keen said that he uses the Multivariate ENSO Index (MEI) for such removal.

And what is the MEI when it is at home? Here’s the description from NOAA:

El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is the most important coupled ocean-atmosphere phenomenon to cause global climate variability on interannual time scales. Here we attempt to monitor ENSO by basing the Multivariate ENSO Index (MEI) on the six main observed variables over the tropical Pacific. These six variables are:

sea-level pressure (P),

zonal (U) and

meridional (V) components of the surface wind,

sea surface temperature (S),

surface air temperature (A),

and total cloudiness fraction of the sky (C).

Now me, I’m a bit wary of the MEI, because of the possibility of it sharing a variable with something that I’m investigating. For example, in the post I did on the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii, cloudiness was a variable because I was looking at solar radiation. However, I used it because Dr. Keen used it, and because for the purposes of my post it turned out the considerations didn’t matter.

The effects of the El Nino don’t happen immediately, of course. In general, the effect of the El Nino on the global temperature lags the El Nino by a couple of months. You can determine the lag by using a “cross-correlation analysis”, which shows the correlation between the El Nino and the variable of interest over a wide range of lags.

So imagine my surprise when I did the cross-correlation between the MEI and the Mauna Loa Observatory temperature and got the following result:

Figure 1. Cross-correlation between Mauna Loa Observatory (MLO) temperatures and the Multivariate ENSO Index (MEI).

Zowie … I was expecting a two or three-month lag, but the peak correlation is not lagged a couple months, a couple of quarters, or even a full year. Instead, peak correlation is at no less than a fifteen-month lag.

Now the joy of science is in the surprises. When I get surprised, I don’t sleep right until I learn more about what it was that surprised me. I couldn’t figure out how it was that Hawaii got basically no correlation for six months, and then after that, the correlation kept increasing until it peaked at fifteen months.

So I made an investigation of the correlation of the MEI with the individual 1° latitude x 1° longitude gridcells of the planetary surface. As you might imagine, at a lag of one month you have the strongest correlation between the MEI and the tropical Pacific. Here’s that map:

Figure 2. Correlation, MEI and 1°x1° gridcells. The dark blue lines outline the areas where the correlation is less than minus 0.2. Red outlines the areas where the correlation is greater than plus 0.2.

You can see that the area of the central Equatorial Pacific has the highest correlation with the MEI. The light blue rectangle shows the NINO 3.4 area, which is used in the same way as the MEI is used, to diagnose the state of the El Nino. So the high correlation there makes sense.

Figure 2 also reveals why the correlation with Hawaii is so low at the one-month lag. It is because Hawaii (black dot above the left side of the light blue rectangle) is very near the edge between the red and the blue areas, where the correlation is small.

To investigate the longer lags, I decided to make a movie so I could understand the evolution of the El Nino variations as they spread out and affected other parts of the world. Here’s that movie. It shows the correlation of the MEI and the individual gridcells at periods from one month to 24 months and then back down again to one month.

Again, more surprises. The correlation dies away quickly in some areas, but in Hawaii it builds until about fifteen months, and then decreases after that.

.

How amazing is that? If you want to know what the temperatures at the Mauna Loa Observatory will be doing fifteen months from now, you can look at the MEI today.

To demonstrate this odd fact, here are the MLO temperatures compared to the Multivariate ENSO Index lagged by 15 months.

And that’s why I love climate science … because there is so much to learn about it.

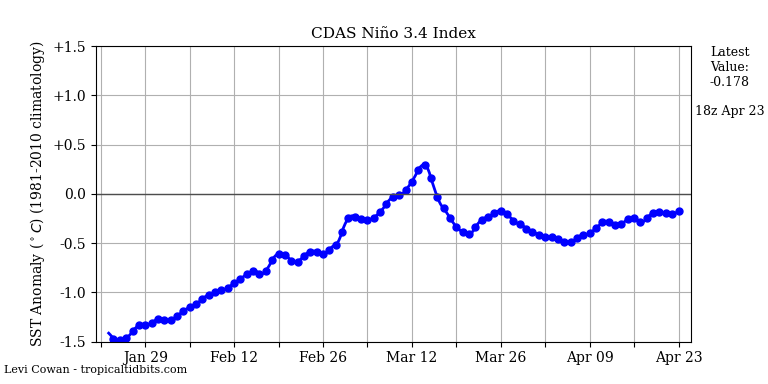

[UPDATE] I got to thinking that I should do the same thing using the NINO34 Index … here is that result. As you can see, it is extremely similar to the MEI graph above.

Here in the forest, after doing most of the work in this post, I was moving my computer files into new computer folders yesterday evening and I managed to destroy about half of them … and my last backup was three weeks ago.

So I was up until 2 AM saying bad words and reconstructing lost functions that went into the bit bucket. Grrrr … then I spent all day today beating my files back into submission so that I could recreate the work that I’d already done on this post. However, it allowed me to clean up some poorly written functions, and I suppose anything worth doing is worth doing twice.

It was also another demonstration of my rule of thumb gained from living about 20 years on tropical Pacific islands, which is:

The Universe doesn’t really give a damn what I think should happen next.

Factcheck: True … the good news is in the corollary to that rule of thumb, which is:

I do have a choice in the matter: I can dig it or whine about it.

Endeavoring to follow my own maxims re my monumental computer blunder, I remain,

Yr. Obdt. Svt.,

w.

I Know This Gets Old But: When you comment, please quote the exact words you are discussing. Misunderstandings abound on the intarwebs. Clarity about your subject can minimize them.

Get a 2 terabyte Passport. Plug it into a USB port a couple of times a week. Run a simple .bat file with some xcopy commands to back up that thing. Every time you do a bunch of work, plug it in, click on the script file icon on the desktop and then keep working. Unplug the Passport and put it on the shelf. If you are running Linux it’s just as easy. Do not run a backup program. Just copy the files. You can then plug it in anywhere and access any file anytime. When it’s unplugged it’s immune to lightning, power outages, etc.

Bingo. Been doing exactly that for years. Simple, inelegant, effective.

I think the super ninos, are likely to have decadol affects, Hear me out, The amount of water vapor that is released into the air by an event that is raising tropical Pacific SST 2C over normal rather than 1C as lets say as a weak to moderate one does is immense, Now again, think about mixing ratios, where does WV makes the greatest impact.. The lower the temp, the more WV has an effect, So what happens? The super nino occurs, Perhaps 2 years later much of the warmer part of the planet is more or less back to normal as we see , After all whats .5 gram/kg of WV over the tropics, or even at 40 north, But where its very cold and dry, its big deal! So it remains warmer in the coldest driest areas. In fact so much so, that I suspect that the function of the Super Nino is to establish a new higher pause plateau, We saw that after 1997-1998 but the fact is that while there is great joy that we had a record drop in temps from the peak of the super nino, the counter to that by someone pushing warming is the satellite temps are at their highest level ever 2 years after an any el nino. Again this has nothing to do with co2, but it will be portrayed that way and a willing media and non observational public will buy it. but the affects of an a super nino may be multidecadol in nature because they would leave the coldest driest areas warmer because of the very slight leftover higher amounts of wv there. . Of course the wild card now is the sun, which was not going into a funk after the last super nino, but is now, In any case, this should make for some interesting testing, My concern is that the state of the oceans being so warm ( and I do not think its because of co2, but a product of many years of action and reaction) , means that low solar decreases the easterlies meaning la ninas are weaker and we are more apt to el ninos, Take a look at the response to the last super nino, vs this one which was feeble compared to the La Nina of 98-2000. So I opine that the drop off from low solar may take longer , but the danger is that once it starts, it may be quite a drop off. Until then the co2 climate control knob people have plenty of observational ammo ( its warm, there is no denying that) to push their missive. Just a thought ( or series of them) peace to all

The warm return wave under the surface of the ocean was too weak to cause El Niño. Now the temperature at the equatorial Pacific is starting to fall again.

Abstract

Despite the tremendous progress in the theory, observation and prediction of El Niño over the past three decades, the classification of El Niño diversity and the genesis of such diversity are still debated. This uncertainty renders El Niño prediction a continuously challenging task, as manifested by the absence of the large warm event in 2014 that was expected by many. We propose a unified perspective on El Niño diversity as well as its causes, and support our view with a fuzzy clustering analysis and model experiments. Specifically, the interannual variability of sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific Ocean can generally be classified into three warm patterns and one cold pattern, which together constitute a canonical cycle of El Niño/La Niña and its different flavours. Although the genesis of the canonical cycle can be readily explained by classic theories, we suggest that the asymmetry, irregularity and extremes of El Niño result from westerly wind bursts, a type of state-dependent atmospheric perturbation in the equatorial Pacific. Westerly wind bursts strongly affect El Niño but not La Niña because of their unidirectional nature. We conclude that properly accounting for the interplay between the canonical cycle and westerly wind bursts may improve El Niño prediction.

https://www.nature.com/articles/ngeo2399

I feel comfortable with the concepts here until I get to this – – –

“- – – low solar decreases the easterlies ”

, then I run into a density in my understanding.

I am not certain what the relationship of the El Nino, La Nina cycle is to “low solar” or indeed exactly what low solar references, unless is it heightened cloud albedo from increased water vapor. Please enlarge upon, “low solar”.

It is interesting to see what thoughts are tumbling out as a result of the arrival of the Willis correlation upon the WUWT following. There have often been acknowledgements that in the study of climate, that really little is known. Here something has been turned up that opens yet one more tiny crack in the efface that suggests that it is possible further efforts at exerting scientific effort is no longer necessary as certain matters are settled.

The Willis correlation video map suggests to me that there may be implications here for weather forecasting in both the longer and medium ranges. The configurations seen on the video seem to show discrete zonal patterns that very well could be sufficiently consistent to define zones of characteristic predictable properties. What other opportunities exist for building a platform enlarging the scope applicable climate? Surely there are many. Certainly the present construct has hardly begun. .

Low solar activity disturbs the ENSO wave and leads to neutral conditions.

http://tropic.ssec.wisc.edu/real-time/mimic-tpw/global2/main.html

ren June 2, 2018 at 10:28 pm

ren, first you’ll have to define what you are calling the “ENSO wave”, I’ve never heard that term.

Next, you need to define “low solar activity” …

Next, you need to demonstrate in some form that what you say is true. I looked at your link. Not one word about solar or ENSO …

Finally, I just looked at a CCF and a scatterplot of sunspots vs MEI … nothing.

w.

In periods of low solar wind activity (low speed and density), stream currents in the upper atmosphere are weak and over the oceans more meridional. That is why the surface temperature of the oceans is dropping now. This is especially visible in the tropical Atlantic. ENSO is a wave because it follows Humboldt’s current.

The activity of the solar wind is very low and falls.

If you look at the graph, you’ll see a wave.

Thanks.

The SST anomaly is based on a 1971-2000 NOAA climatology.

http://cr.acg.maine.edu/wx_frames/gfs/ds/gfs_world-ced_sstanom_1-day.png

Logical conclusion Joe.

I note that Bob Tisdale thought the big El Ninos caused a step-change in temperatures. I was of the camp that there is just a 3 month lag period.

But now we see that the 2015-16 super-el-niño has maybe caused another step-change. It might dissipate over time but it is still there none-the-less. There has to be a logical reason if this is indeed the case.

Bill Illis:

You say “There has to be a logical reason if this is indeed the case”

Yes, there is a logical reason, and this is indeed the case.

All El Ninos are caused by a significant reduction in the amount of SO2 aerosols in the atmosphere, normally in the aftermath of a VEI4 or larger volcanic eruption.

However, between 2014-16, Chinese SO2 aerosol emissions dropped by approx. 29 Megatons, a massive and unexpected amount, and the resultant cleaner air was responsible for the higher temperatures that occurred.

Until that reduction is offset (probably by increased emissions from India, or a large volcanic eruption) warmer temperatures will continue.

(The 1997-98 “super El Nino” was caused by a 7.7 Megaton reduction in SO2 aerosol emissions, due to global Clean Air efforts)

Mr. E, as always, great post. In times past I was a chemist. Reading your post concerning the stability of the temps in and around the Hawaiian islands , I was thinking in terms of “buffered chemical solutions”. That the islands were a “buffered weather/ climate system. (I had similar thoughts reading your post on the stability of weather/climate of Ireland.). That the waters in and around the islands were the “buffer”.

If the above has any validity, the humidity (actually relative humidity, I think) would have “surged” in response to any “cooling” effect from volcanic aresols. ( It did snow in New England in July in tesponse to a surge in volcanic aresols from an volcanic eruption in the

Cascades, back when?)

Does the MLO and the various weather recording stations scattered throughout the islands record RH?

I am not equipped to access the records.

I am still digesting your latest post with respect to the above thoughts.

Enough said, a great couple of posts, Mr E,

keep them coming.

Respectfully

Willis.

Before I start – I dont know a great deal about oceanic weather systems.

However, you said in a previous reply (paraphrased), that the Pacific cannot operate as a heat sink, to stabilise weather, as ocean temperatures can and do vary considerably with the seasons. … But to what depth? As the following Argo graph demonstrates, significant temperatures go down to 1500m, and the majority of this volume will not vary with the seasons.

So what would be the seasonal oceanic energy variation be, compared to the total energy contained in the top 1,500m? And if the top layers of the ocean cooled to normal winter temperatures for a significant period (ie, in years following a significant volcanic eruption), what would be the rate of energy transfer between the lower and upper layers? How long could the oceans keep the Earth at temperate temperatures, if there were little or no insolation?

I still think that the oceanic storage system is highly influential to the stability of our weather and climate, as I feel it every winter. Briain’s balmy winters, in comparison with Russia, are solely dependent upon the oceanic energy storage system, and the release of that energy back into the atmosphere.

Just wonderin’

Ralph

[img]http://www.euroargo-edu.org/img/6900211a_ove_temp.png[/img]

http://www.euroargo-edu.org/img/6900211a_ove_temp.png

http://www.euroargo-edu.org/img/6900211a_ove_temp.png

How do we get images to display, using this new comment system…?

Tried [img] and but no luck yet….

R

I’ve been watching and pondering the ‘movie’ quite a bit. Thoughts in my mind are all over the place as to all that could be interpreted from it. Is there any way to freeze of slow the movie?

It would be interesting if cloud cover could be combined with the movie but would likely need another global movie side by side or maybe a ‘dot matrix’ style of cloud indicator. Maybe a focus on the Atlantic as well as another on the Pacific.

Maybe I have just been watching too much movie reruns.

GAWD! How I love readin me some Willis!!!! Childish curiosity, backed by adult abilities, presented perfectly to his fellow “kids”…I’ve been here over 8 years, and I still wait with “happy feet” when I see a Willis post! Thank you Willis, thank you Master-Watts.

This deserves an article Willis. Your correlation seems to be sound.

I repeat:

If there is a multi-month lag between El Nino releasing heat into the atmosphere,

why is there no lag between ENSO

and inter-annual variations in length of day?

The variations in length of day are caused the atmosphere expanding in response to the heat released by El Nino – and it happens instantly.

It must be an inconvenient fact for fans of the mysterious “lag”, for this very question has been ignored fanatically for many years.

First, cut the BS about “ignored fanatically”. This is the first time I’ve heard of this question, and it’s not exactly a burning issue.

Second, there is no “multi-month lag” between MEI and temperature. It’s one month between the CERES temperature and MEI.

Third, I just went and got the daily LOD data from here. I converted it to monthly, removed the seasonal and secular variations. After that, I get … a one month lag between MEI and LOD.

Fourth, the inaccuracy in the CCF is at least one month.

Fifth, the “lag” is merely the time of maximum correlation. The effect starts at t=0.

Finally, next time don’t be so damn snarky or you won’t get an answer from me.

Second, there is no “multi-month lag” between MEI and temperature. It’s one month between the CERES temperature and MEI.

quote:

===========

In general, the effect of the El Nino on the global temperature lags the El Nino by a couple of months. You can determine the lag by using a “cross-correlation analysis”, which shows the correlation between the El Nino and the variable of interest over a wide range of lags.

So imagine my surprise when I did the cross-correlation between the MEI and the Mauna Loa Observatory temperature and got the following result:

Zowie … I was expecting a two or three-month lag, but the peak correlation is not lagged a couple months, a couple of quarters, or even a full year. Instead, peak correlation is at no less than a fifteen-month lag.”

============

“Third, I just went and got the daily LOD data from here. I converted it to monthly, removed the seasonal and secular variations. After that, I get … a one month lag between MEI and LOD.”

I’m happy with a one month lag for the global temperature metric. It’s close enough to instant for me. But many people have cited multi-month lags over the years, including a ~6 month lag once mentioned by Lord Monckton.

Could you please post a url to the graph you made comparing inter-annual variations in length of day with the MEI, when you have a spare moment?

I would very much like to see it.

I had a hard time trying to identify the correct version of the LOD data file at the official repository (ITER?) – and I am very poorly equipped to filter and graph the data in any case. (I don’t even have a copy of Excel).

Thanks.

Algorithm, yep, you can get different numbers depending on just which measure of El Nino you use (MEI, NINO34, SOI, etc.) and which global dataset you use (HadCRUT, CERES, Berkeley Earth, GISS, etc.).

I didn’t compare the MEI with the LOD. All I did was do the CCF (cross-correlation function). There’s a good description of the analysis method here.

The data is at the location I linked to in my post.

w.

Mr. Algorithm, some points:

• Cut out the “ignored fanatically” BS. This is the first time I’ve seen the question, and it is hardly a burning issue in climate science.

• The lag between the MEI and the CERES temperature is not “multi-month”. It’s one month. The same is true for the NINO34 index. However, see the discussion of uncertainty below.

• I went and got the LOD data from here. It’s daily data. I averaged it to monthly. Then I removed the seasonal signal. Then I removed the long period signal. Then I ran a cross-correlation analysis on the result …

• Have you done the same? Or are you just “fanatically ignoring” the data and believing what someone else tells you?

• I ask because I found that there is a one-month lag between NINO34 and LOD … go figure.

• Curiously, MEI actually leads LOD by one month … but the correlation is NOT statistically significant.

• It’s not significant because the uncertainty in the cross-correlation is at least one month, might be two months. For example, at zero lag the correlation between NINO34 and LOD is 0.117 ± 0.04.

At lag 1, the correlation is larger, 0.150 ± 0.04.

And at lag 2, the correlation is smaller, 0.126 ± 0.04.

So nominally we say it’s a 1 month lag.

HOWEVER, and it’s a big however, since these three standard errors all overlap, these results are NOT statistically significantly different from each other. So we cannot say with statistical certainty whether the lag between LOD and NINO34 is zero, one, or two months.

• In other words, you’ve worked yourself up into a snarling mess over something that isn’t even true.

• Next time, lose the attitude or I won’t be the one to answer you.

Regards,

w.

As I preach to people: “there are two kinds of storage devices you can have on your computer: ones that have failed and ones which will fail. Regular backups are the necessary consequence of that reality”. Add to that: “there are two kinds of computer users: ones that have made dumb mistakes and ones that will make dumb mistakes”.

Even though I have preached that line for 20+ years, I find I fail to heed my own advice and get burned from time to time. Damn, but maintaining regular reliably usable backups takes work. Verifying your backups are actually usable takes more work. I have regular and I believe complete backups from a system which failed that I cannot use because the format is (I now find) specific to that environment which I no longer have, and which I also now find I cannot recreate on my available hardware.

So add to the two backup principles above: “You cannot assume what you have not verified”.

Eternal vigelance is the price of data integrity.

I have primary source as well as backup on 51/4″ floppies from the early 1980s — not to speak of magnetic tape from the 70’s. (Ironically my boxes of card decks are of course still readable by just looking at the print at the top of the cards.) Assuming that the 51/4″ floppies are still readable, where might I send them to extract that data?

NOAA, send them to RetroFloppy. They’ll give you a quote first.

w.

Some years ago i bought a USB floppy disk reader and put my stuff in a separate storage. Are the still available? dunno. Someone seems to have swiped mine.

“Next time, lose the attitude or I won’t be the one to answer you”

Willis, one person was getting personal, and it was not Kwariizmi. Get your gallstones seen to……grin

BA2204 June 2, 2018 at 9:43 pm

Kwarizmi was accusing people of deliberately “ignoring fanatically” some obscure pseudo-fact that he thinks is important. That is having an attitude and getting personal, whether you see it or not.

Now, you’ll note that despite his unpleasant manner, I went to some lengths to find and download the data that Kwarismi didn’t have … and to do the analysis he didn’t do and apparently can’t do … and to explain the results to him in some detail.

However, I’m not gonna pretend that his request was politely phrased.

Call me crazy, but I don’t like being accused by some anonymous internet popup of deliberately ignoring inconvenient facts. I don’t do that. So let me invite you to go grin at someone else, and to stuff your gallstones up your … gall bladder …

w.

I was expressing frustration at the lack of response from anyone over several years to my repeated mention (eg) of what you call “an obscure pseudo-fact”–one that I demonstrated with a graph made by overlaying the interannual LOD signal on the MEI, with no lag.

But you took my phrase “fanatically ignored” personally. Perhaps I should have explained myself better. Or maybe you have too much cortisol in your bloodstream today.

====

“How amazing is that? If you want to know what the temperatures at the Mauna Loa Observatory will be doing fifteen months from now, you can look at the MEI today.”

====

How amazing is THIS?

If you want to know what temperature trends for the entire planet will be doing 6 years from now, you can look at multi-decadal variations in LOD today.

Khwarizmi, I took a look at that paper a while back. My problem was that I was totally unable to reproduce their results. I just tried again, no joy. I got the LOD data from the UK Home Office. It looks very much like the data in Figure 2 of your link.

Then I compared it to the HadCRUT4 data. Yes, there is an APPARENT lag between LOD and temperature … however, there are a couple of problems.

First, the two datasets are not well correlated (R^2 = .3, but p-value of 0.33, not statistically significant). This is because of the high Hurst Exponents of the two datasets (0.8 and 0.9)

Second, the best fit at a lag of 4 years (correlation 0.551 ± 0.07) is barely different from and not significantly better than that at no lag (correlation 0.549 ± 0.07). Since the errors overlap, we cannot say that the 6-year lag is a better fit. Here’s the cross-correlation analysis including the one-sigma errors:

This strongly suggests that the 6-year lag is apparent rather than real.

And this makes perfect sense. We know and have solid theoretical reasons why temperature affects LOD. We have no theoretical reason why a change in LOD today would affect the weather in six years.

Best regards,

w.

The FAO study was unique in predicting a return to dominance of meridional circulation, which seems to have occurred, hence the popularity of the phrase “polar vortex” in the US meteorological lexicon in recent years — plus record snow in China, US and Europe, “snowmageddon”, and bipolar swings in climate propaganda,

aka: global warming makes winters colder/milder/colder/milder, etc. (things we’re expected to forget between news cycles)

-LOD superimposed on dT with a 6 year lag:

http://www.fao.org/docrep/005/y2787e/y2787e03b.htm#FiguraB

While not 100 % perfect, it is a remarkable fit with regard to trends, not temperatures per se, as is your own graph of MEI vs MOA temps with a 15 month lag. The 6 year lag seems to be the best match.

It is an intriguing mystery as to why temperature changes after -LOD (on multi-decade scale), and not before. The paper says it remains a useful predictive index, even though we don’t understand the mechanism.

Many pharmaceuticals are produced and sold today because they work, even though we don’t understand the mechanism. In fact, pharmaceuticals lacking a mechanistic category (e.g., beta blocker, 5HT3 receptor antagonist, proton pump inhibitor, etc) are generally classified as “novel,” being a cryptic admission that we don’t entirely understand how they work at this point.

Anyway, your MLO temp vs MEI graph is impressive – it don’t show up on my first visit, or would have said so already.

“The periods dominated by any single form of atmospheric circulation have alternated with a roughly 30-year period for the last 100 years. These periods were named “Circulation epochs”. These may be pooled into two principal groups: meridional (C) and combined “latitudinal” epochs (W + E): (W + E) = – (C)

Meridional (C) circulation dominated in 1890-1920 and 1950-1980. The combined, “zonal” (W+E) circulation epochs dominated in 1920-1950 and 1980-1990. Current “latitudinal”(WE) epoch of 1970-1990s is not completed yet, but it is coming into its final stage, and so the “meridional” epoch (C-circulation) is now in its initial stage. (It will be useful for the reader to note here the relation that shows that the “transition” from C to W-E is continuous, and the equation balances to 100%, in the form of a simple graphic without any other variables included).”

This is consistent with the observations of pressure over the polar circle.

“This study showed that the disturbances of the troposphere circulation associated with SA/GCR variations

take place over the entire globe. The spatial structure of the observed pressure variations is determined by the

influence of SA/GCR on the main elements of the large-scale atmospheric circulation (the polar vortex, the

planetary frontal zone and extratropical baric systems). The temporal structure of the SA/GCR effects on the

atmosphere circulation at high and middle latitudes is characterized by a ~60 yr periodicity, with the changes

of the correlation sign taking place in 1890-1900, the early 1920s, the 1950s and the early 1980s. The ~60 yr

periodicity is likely to be due to the changes of the epochs of the large-scale atmospheric circulation. A sign

of the SA/GCR effects seems to be related to the evolution of the meridional circulation C form. A

mechanism of the SA/GCR effects on the troposphere circulation may involve changes in the development of

the polar vortex in the stratosphere of high latitudes. Intensification of the polar vortex may contribute to an

increase of temperature contrasts in frontal zones and an intensification of extratropical cyclogenesis. ”

http://geo.phys.spbu.ru/materials_of_a_conference_2010/STP2010/Veretenenko_Ogurtsov_2010.pdf

Joe Bastardi June 2, 2018 at 6:25 am

I’m sorry, but this is not true. At say 26°C you get total precipitable water of 35.4 kg/m2. Go up one degree and that increases by about 3.3 kg/m2, a 9% increase.

One more degree and it goes up another ~ 4.3 kg/m2, an 11% increase. See here, Figure 2, and the formula in the endnotes relating SST and total precipitable water (TPW).

Over that short a thermal range (2°C) the relationship is not far from linear. As a result, the increase in water vapor is far from “immense” as you say.

Best regards,

w.

Precipitable water vapour in the atmosphere is function of square of wet bulb temperature multiplied by a seasonal factor times. = W = a x square of (Tw).

Wet bulb temperature is a function of dry-bulb temperature multiplied by 0.45 plus relative humidity and pressure function.

So, precipitable water vapour is not a linear function of temperature.

sjreddy

Dr. R, I did NOT say it is linear. I referred you to my post, Figure 2. As you can see, it’s roughly linear in the lower temperatures but not in the upper range.

The formula relating ocean temperature and total precipitable water (yellow line) is

TPW = – 13.5 * log(-1 + 1/(0.00368 * SST + .887)) -19.1

Best regards,

w.

Willis,

Thanks for the link https://wattsupwiththat.com/2016/07/precipitable-water-redux/ above. I have read all your previous posts but as time goes on the info/knowledge is filed away in my mind and when I need to revisit the pertinent post …. well …. I can’t remember where I read it and then there’s the ‘lazy factor’ on searching for it as well as the time factor of the current discussion thread.

Anyway, please check back on this post over the next couple of days. I have a bunch of thoughts running around in my head and need to sort it out and try to figure out how to express it in an elevator comment.

I’m focused on upwelling and downwelling IR between the surface and developing clouds/storms and leading cloud interface. It’s one of those times where you ‘see’ something but just can’t put your finger on it or express it.

Anyway, real life chores are calling for my attention now.

Willis,

There was an article about a 15 month wind pattern in the Pacific ocean related to the ENSO.

Climate researchers discover new rhythm for El Niño

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/05/130527100628.htm

Why El Niño peaks around Christmas and ends quickly by February to April has been a long-standing mystery. The answer lies in an interaction between El Niño and the annual cycle that results in an unusual tropical Pacific wind pattern with a period of 15 months, according to scientists.

This 15 month period change in the wind pattern beats with the 12 month seasonal cycle to produce

an alignment with the seasons, once every 5 years. The ENSO cycle is roughly 4.5 – 5 years in length.

(15 x 12) / (15 – 12) = 60 months = 5 years

Could this wind pattern be related to the lag you are seeing?

Unlike many tropical Pacific islands, the Hawaiian chain lies well outside the narrow equatorial belt that encompasses various Nino indices. If one avoids the mistaken notion that the latter closely represent the SST time histories in Hawaii, then there’s scarcely any “mystery” to the fact that the weak cross-correlation with Mauna Loa monthly temperature peaks 15 months later. It’s most likely the residual effect of mass and heat transport by the great North Pacific gyre reaching Hawaii with such a delay. (At an average speed of one knot, such transport would cover ~11 thousand n. miles during that time.) Scores of such delayed and diffused arrivals of mass properties in locations far downstream from the area of origination have been noted in the field by analysts. The present case is scarcely new or particularly noteworthy in that geophysical context.

Gosh, 1sky1, could you possibly be snarkier in presenting, as though it were new information, things that have already been commented on and discussed at length in this very thread?

You really should read the comments first, then you might have a chance of not sounding like a patronizing supercilious jerkwagon …

w.

I read the articles, not the comments. It’s jerkwagons who write the former whore a re such.

There goes Willis again, calling people names: “patronizing supercilious jerkwagon”

Actually, C. Paul, I merely gave 1sky1 some very valuable life advice on how he might avoid sounding like a patronizing supercilious jerkwagon …

w.

Actually Willis Eschenbach, https://www.realskeptic.com/2013/12/23/anthony-watts-resort-name-calling-youve-lost-argument/