Guest essay Steve Goreham

Originally published in The Washington Times

Sea level rise is the greatest disaster predicted by Climatism, the belief in catastrophic climate change. Today, leading scientific organizations support the idea that the ocean level is rising due to man-made emissions. Further, they claim to be able to measure ocean level to a high degree of accuracy. But a look at natural ocean variation shows that official sea level measurements are nonsense.

The theory of man-made climate change warns that human emissions of greenhouse gases will raise global temperatures and melt Earth’s icecaps, causing rising oceans and flooding coastal cities. Former Vice President Al Gore’s best-selling book, An Inconvenient Truth, showed simulated pictures of flooding in South Florida, the Netherlands, Bangladesh, and other world locations. Dr. James Hansen predicted an ocean rise of 75 feet during the next 100 years.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stated in 2007, “Global average sea level rose at an average rate of 1.8 mm per year over 1961 to 2003. The rate was faster over 1993 to 2003: about 3.1 mm per year.” This translates to a 100-year rise of only 7 inches and 12 inches, far below the dire predictions of the climate alarmists.

But three millimeters is about the thickness of two dimes. Can scientists really measure a change in sea level over the course of a year, averaged across the world, which is two dimes thick?

Today, sea level is measured with satellite radar altimeters. Satellites bounce radar waves off the surface of the ocean to measure the distance. Scientific organizations, such as the Sea Level Research Group at the University of Colorado (CU), use the satellite data to estimate ocean rise. The CU team estimates current ocean rise at 3.2 millimeters per year.

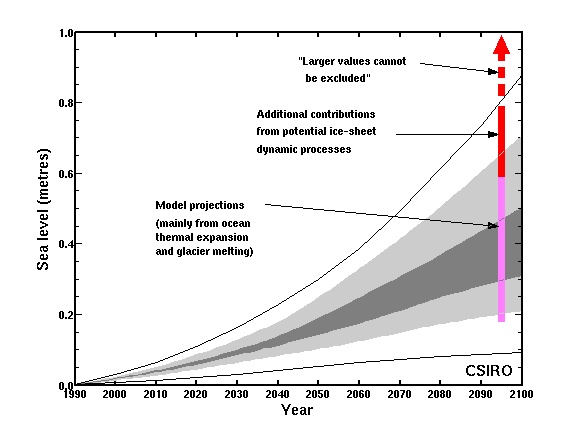

The organizations AVISO (Archiving, Validation, and Interpretation of Satellite Oceanographic Data) of France, CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization) of Australia, and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) of the United States agree with the University of Colorado that seas are rising three millimeters per year. Given the huge natural variation in global sea level, the three millimeter number is incredible. The fact that four different organizations have arrived at the same number is suspect.

As Dr. Willie Soon of Harvard shows, ocean level variation is large and affected by many factors. If temperatures rise, water expands, adding to sea level rise. If icecaps melt, levels rise, but if icecaps grow due to increased snowfall, levels fall. If ocean saltiness changes, the water volume will also change.

The land itself moves continuously. Some shorelines are rising and some are subsiding. The land around Hudson Bay in Canada is rising, freed of ice from the last ice age. In contrast, the area around New Orleans is sinking. Long-term movement of Earth’s tectonic plates also changes sea level.

Tides are a major source of ocean variation, primarily caused by the gravitational pull of the moon, the sun, and the rotation of the Earth. Ocean water “sloshes” from shore to shore, with tides changing as much as 38 feet per day at the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia. The global average tide range is about one meter, but this daily change is still 300 times the three-millimeter change that scientists claim to be able to measure over an entire year.

Storms and weather are major factors affecting satellite measurements. Wave heights change by meters each day, dwarfing the annual rise in ocean level. Winds also change the height of the sea. The easterly wind of a strong La Niña pushes seas at Singapore to a meter higher than in the eastern Pacific Ocean.

Satellites themselves have error bias. Satellite specifications claim a measurement accuracy of about one or two centimeters. How can scientists then measure an annual change of three millimeters, which is almost ten times smaller than the error in daily measurements? Measuring tools typically must have accuracy ten times better than the quantity to be measured, not ten times worse. Dr. Carl Wunsch of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology commented on the satellite data in 2007, “It remains possible that the database is insufficient to compute mean sea level trends with the accuracy necessary to discuss the impact of global warming—as disappointing as this conclusion may be.”

Scientists add many “fudge factors” to the raw data. The same measurement taken by each of the three satellites, TOPEX, JASON-1, and JASON-2, differs by 75 millimeters and must be corrected. As a natural adjustment, researchers add 0.3 millimeters to the measured data, because ocean basins appear to be getting larger, able to hold more water, and reducing apparent ocean levels.

Tide gauges are also used to “calibrate” the satellite data. But gauge measurements are subject to errors of one or two centimeters, again many times more than the sea level rise to be measured.

Clearly, the official three millimeter sea level rise number is a product of scientific “group think.” Not only is this number far below what can be accurately measured, but all leading organizations support this nonsense number. Could it be that our leading scientists must endorse sea-level rise to support the ideology of man-made global warming?

Steve Goreham is Executive Director of the Climate Science Coalition of America and author of the book The Mad, Mad, Mad World of Climatism: Mankind and Climate Change Mania.

„But a look at natural ocean variation shows that official sea level measurements are nonsense.”

Not at all. A look at the ‘natural ocean variations’ shows a significant main frequency of 6.30 periods per year. To understand the whole plot the precise value of the frequency suggests that it is more fruitful to analyse the ‘natural ocean varitations’ instead of a stupid doubtful sea level. The main sea level oscillation of 6.30 periods per year can be shown by removing the linear increase of 3.24 mm per year. The amplitude seems to be between 5 mm peak to peak until 10 mm peak to peak. But the amplitude not the point. There is an interesting relation between the frequency of 6.30 periods per year and the phase of a solar tide function from the planetary couple of Mercury and Earth. Both planets have big densities and because Mercury has an elliptic path around the Sun, the resulting solar tide function is complex. However, the astonishing point is that ‘spring tides’ from this function on he surface of the Sun are in phase with the positive peaks of the terrestrial sea level oscillation frequency of 6.30 periods per year and vice versa, negative peaks of the sea level oscillation frequency are in phase with solar ‘nip tides’ from this couple.

From astronomy books we can take the periods of Mercury with 4.15207 per year and period of the Earth with 0.9998 per year. The synodic period of this couple is the difference of both periods (4.15207 – 0.99998 = 3.15209 periods per year. Because a (solar) tide function is twice the synodic function, because springtides occur as well on conjunctions and also on oppositions, the solar tide frequency of Mercury/Earth is twice the synodic period (2 x 3.15209 = 6.30418 periods per year). To have an impression of this plot one can draw the relevant functions superimposed in a graph for the last four years. The sea level data from UC removed by the linear increase of 3.24 mm per year is drawn in thick light blue. The weighted solar tide function of Mercury/Earth because of the extreme ellipticity of mercury is drawn in thin black; the unweighted function is drawn in thin light gray. Because of the delay of the ocean impedances, the ENSO index (MEI) take place about 0.436 years later (thick dark blue). It can be seen, that as well the global temperature measured by UAH (thick red curve) and the sea level curve is impressed by this delayed MEI.

http://www.volker-doormann.org/images/sea_level_oscillations.gif

All these facts suggest an immediate heat effect on the oceans from the sun, and maybe the sea level oscillations amplitude is a result of the property of water which volume grows with temperature over 4° Cel. It is clear that other possible couples create also solar tides, with lower tide strength than the couple of Mercury/Earth, but this out of this comment. I think from the view of science it is wasted time working on amplitudes of global temperatures or sea level trends as climatism has done; frequency analysis of spectra instead can produce significant temperature frequencies, which can be identified as part of the climate ages and decades. No one is helped if the conclusion of a hard work is ‘nonsense’.

V,

This is only true for a single measurement. If you have many measurements the uncertainty error is given by the formula for the Standard Error of the Mean (SEM):

SEM = SE /

SE = Standard error of one single measurement

N = Number of unbiased measurements

That means that if you have many unbiased measurements the final measurement error becomes very small.

Example: say that the error for one single measurement is 30 cm

100 unbiased measurements then give a SEM of 3 cm

10000 unbiased measurements give a SEM of 3 mm.

From Jan Kjetil Andersen September 22, 2013 at 10:58 am:

You have succumbed to a common fallacy. You are not taking multiple measurements of the same thing at the same time, you are taking single measurements at different times.

I measure the length of a rod to +/-0.5mm, then I measure it every hour until I have 100 measurements. When can I claim an uncertainty of only +/-0.05mm? The length varies greatly, now it is 952.5mm, an hour later it could be 1127.0mm, or 852.5mm. What uncertainty can I claim?

Sea level is single measurements at different times. Your assumption is flawed.

kadaka (KD Knoebel) says:

September 22, 2013 at 1:39 pm

Kadaka, The analogy with measuring a rod is not is not a very good one.

Sea levels are not measurements of the same thing, it is measurements different places with many different uncertainties each place and at each time. There are tidal waves and surges due to air pressure just to mention two of them.

And there are plenty of other measurements from tide gauges which can be used to calibrate the satellite measurements.

This means that it is correct to use Standard Error of the Mean for these different measurements.

Dou you really think that all these scientific reports on sea level rise make this error on some simple math?

” John Finn says:

September 21, 2013 at 3:39 am

No – the ‘special magic’ is just the use of basic statistics. For example, using a measuring stick with just 2 measurements at 5’6” and 6’ it would be possible to provide an accurate estimate of the mean height of US (or UK) males. Take a random sample of 1000 UK (or US) males, then use the stick to ‘measure’ their heights. ”

Your example perfectly demonstrates the problem that the author raised. You have used a ‘measuring stick’ which can accurately measure to at least 1″ for males with an average height of 70″ or so. Thus, in a random sample you can find the mean of the sample. Now try to measure grains of sand using the same ruler. Not so easy, is it?

Error generally has 2 components, systematic and random. While statistics can be used to reduce random error uncertainty it cannot be used to remove systematic error. Only calibration with better equipment can do this. if I used a ruler with 3″ broken off the end to measure all males I would conclude that average male height was 67″.

There is also nothing to suggest that the systematic error itself will not vary over time. Aging is a well known effect in the world of precision electronics. Essentially the ruler might grow longer (or get shorter) over time and no-one would even know unless they calibrate it against another, more accurate, ruler.

To:

Greg Goodman says:September 21, 2013 at 6:30 am

Leonard Weinstein says:September 21, 2013 at 6:39 am

I’ve been traveling for a couple of days.

In reference to my post:

Steve Keohane says:September 21, 2013 at 6:07 am

Philip Bradley says:September 21, 2013 at 4:33 am

Inverse Barometer Adjustment

The Inverse Barometer (IB) is the correction for variations in sea surface height due to atmospheric pressure variations (atmospheric loading). It can reach about ±15 cm and it is calculated from meteorological models.

The mass of the atmosphere doesn’t change. Therefore, differences in atmospheric pressure on sea level, average out to zero.

Excellent point, thank you.

I did not give an explicit context for my remark. What occurred to me was that at any given instant, a pressure adjustment would not be needed as the only differences in that instant are local pressures. Even over a day or whatever interval the measurements are taken, the change in mass has to be insignificant.

From Jan Kjetil Andersen on September 22, 2013 at 10:21 pm:

That shows how much you know. If measuring the depth of a river or lake, you could very well be measuring with a rod or stick, length from bottom to surface.

Likewise with sea level gauges, could be firmly mounted in the water and you’re taking a length measurement. Maybe it’s a sliding rod mounted in a holder, bottom of rod has a float that rests on the water, and you’re taking a length measurement.

Likewise the satellite is taking a length measurement.

In every case, for the same spot, you are taking a length measurement. Some time later, you take another length measurement at the same spot. What did I say?

Sea level is single measurements at different times.

This is true for every single spot where you are monitoring the sea level.

Again, your reasoning is flawed.

kadaka (KD Knoebel) says:

September 23, 2013 at 8:38 pm

Kadaka, the important point is to distinguish between random errors and systematic errors. You can reduce the random errors by taking many measurements, but you cannot reduce the systematic errors that way.

The systematic errors with your rod example would be that the rod was inaccurate, and the random error would be the accuracy of reading the rod and the accuracy of the placement of the rod.

The latter errors can be reduced by repeating measurements. If you doubt this, try to measure the length of your house several times with a short yardstick. The results will usually vary by a few millimeters, but after a few times you will be quite sure that the correct answer is near the average value of your different results. The more times you try, the surer you will be.

On the other hand, the systematic error could be reduced by comparing the rod measurements with other measurements of the same length. If we for instance measure the same length with both a laser and a rod we can use the laser result to calibrate the rod and therefore reduce the systematic error.

This is similar to how the results from the gauges are used to calibrate the satellite measurements.

The random errors in satellites, which consist of for example electronic noise, can be reduced by repeating measurements. The systematic errors can be reduced by calibrating the instruments with other measurements.

A description of the various corrections used in satellite measurements are found at: http://www.cmar.csiro.au/sealevel/sl_meas_sat_alt.html

@ur momisugly Jan Kjetil Andersen on September 24, 2013 at 8:05 am:

Why are you claiming to disprove what I said by using examples of something else?

The length of the house is not expected to vary, it should remain the same for decades. Thus your example is many measurements of the same amount reducing the error.

Sea level is still single measurements at different times. The sea level varies. It varies enough to justify the inverted barometer adjustment. It varies by lunar cycle. You take a single measurement at a single spot, repeat at that spot at different times.

Reducing error as you had stated requires multiple measurements of the same thing, namely the same sea level at the same spot at the same time. The length of my house is time independent, sea level is very much not time independent. If you had, say, five calibrated instruments all taking the same measurement at the same instant, then you can combine and reduce uncertainty as stated.

kadaka (KD Knoebel) says:

September 25, 2013 at 2:58 pm

The fact that the se levels varies complicates the measurements, and it also complicates the example, and that is why I chose a non-varying example above.

However, the logic still applies. The variance of the sea level is known, and it is unbiased for all measurements, i.e. you would have just as many measurements with high tide as with low tide, just as many with low air pressure as with low air pressure. The tides and air pressures or any other known variables will not pose any bias towards higher or lower sea level. This means that the method of reducing random errors by many measurements still apply since we are only interested in the average value.

Consider this: You make 10000 measurements of sea levels and get a standard deviation of +/- 1 meter. You know that some of this deviation is due to the actual deviation of the sea level and some is due to random errors in the measurement equipment. You can then still use the rule of the least squares to spot the average value of the sea level with great accuracy (1 meter divided by the square root of 10000).