Guest post by Bob Wentworth, Ph.D. (Applied Physics)

I’ve been thinking about some ideas that WUWT contributor Willis Eschenbach (WE) has proposed. In particular, WE has suggested that tropical cumulus clouds and thunderstorms provide a “thermostatic mechanism” that helps to stabilize the temperature of the Earth within a narrow range. WE has also offered a procedure for predicting surface temperatures changes in response to increased radiative forcing.

I find both these ideas intriguing. Yet, there are assumptions implicit in WE’s thermostat hypothesis and predictive procedure—and I haven’t been at all certain that those assumptions are valid.

So, I wanted to do what I could to check those assumptions.

The Earth is a complex thermodynamic system. When it comes to understanding thermodynamic systems, my experience is that verbal reasoning often leads to incorrect conclusions. So, I always want to know what the what the math and physics tell us.

I’m not about to try to produce a complete, realistic model of Earth’s climate. However, I decided to apply math and physics to a simplified “toy model” of the Earth and its atmosphere.

Simplified models get some things right, and other things wrong. They’re not entirely trustworthy. Yet, such models can still offer valuable insights, beyond what one can get to with verbal reasoning alone.

With that in mind, I’ve analyzed a toy model I call “Thunderstorm World,” to see what light it could shed on WE’s procedure and hypothesis.

I’ve applied this model to examining these questions:

- Does WE’s procedure for predicting how surface temperature changes in response to forcing seem likely to provide valid predictions?

- Does it seem likely that tropical cumulus clouds and thunderstorms might regulate the temperature of a planet to keep it within a narrow range?

Overview

This is a fairly long essay. So, I’ll offer an overview, and you can decide how much of the detailed exposition you want to read.

I describe the Thunderstorm World (TW) model, a simple model of a planet and its atmosphere which includes convective and radiative heat transfer and cloud-induced albedo changes.

The TW model exhibits strong convection and cloud formation at low latitudes. Among other results, the model yields a curve of surface temperature vs. total surface irradiance. This curve is qualitatively similar to the curve that emerges from measurements on Earth. This similarity offers a measure of validation for the model.

I apply a procedure proposed by Willis Eschenbach (or my understanding of that procedure) to trying to predict the response of the TW model to a “forcing” due to an increased concentration of greenhouse gases. Unfortunately, the procedure predicts an increase in mean global surface temperature that is too small by 45 percent. The procedure also fails to correctly predict the variation of temperature with latitude. I identify two mistaken assumptions implicit in the procedure that lead to these flawed predictions.

I examine whether tropical thunderstorms (or, more precisely, low-latitude convection and cloud formation) moderate or limit increases in planetary temperature. Within the TW model, it turns out that convection and cloud formation do moderate temperature increases. But these mechanisms don’t impose any hard limit on such increases. Although the onset of tropical convection might appear to act as a “thermostat” limiting surface temperature, in the TW model, the setting of this “thermostat” is relative to the temperature of the upper layer of the atmosphere. So, if a “forcing” warms the upper troposphere, then tropical surface temperatures can also rise.

Thus, to the extent that the TW model bears a relationship to real-world climate dynamics, the results of the model suggest that (a) the proposed procedure for predicting responses to forcing may not be trustworthy, and (b) tropical thunderstorms likely moderate but don’t place any absolute cap on planetary warming.

The Thunderstorm World Model

The Thunderstorm World (TW) model is designed to be as simple as possible while still accounting for convective heat transfer, cloud formation, radiant heat transfer, and variations in surface temperature.

To this end, the TW model assumes:

- The planet has a uniform surface, high thermal inertia, rotates rapidly, and has no inclination, so that diurnal and seasonal temperature variations can be ignored, and there is no variation with longitude. Temperatures and energy flows depend only on the latitude, 𝛳.

- The atmosphere has two layers. Each layer of the atmosphere is characterized by a single temperature at a given latitude.

- Although the surface temperature, T₁(𝛳), and the temperature of the lower layer of the atmosphere, T₂(𝛳), vary with latitude, the temperature of the upper layer of the atmosphere, T₃, is the same at all latitudes. (On Earth, the average temperature in the upper troposphere at a pressure of 190 mbar is only weakly dependent on latitude, so this assumption of constant temperature isn’t unreasonable.)

- Convection happens whenever the temperature difference between the surface and the lower atmosphere layer, or between the lower and upper atmosphere layers, exceeds a threshold value 𝚪H, where 𝚪 is the adiabatic lapse rate and H is the elevation change between layers.

- The heat transfer rate associated with convection is assumed to be proportional to how much the temperature difference exceeds 𝚪H.

- When convection occurs at the surface, this is assumed to lead to cloud formation which leads to reflection of shortwave radiation from the Sun. This increase in albedo is assumed to be proportional to how much the temperature difference exceeds 𝚪H.

- The layers of the atmosphere have radiative properties similar to those assumed in my prior essay, Atmospheric Energy Recycling. Each layer of the atmosphere absorbs fully a fraction f of thermal radiation wavelengths, and is transparent to a fraction (1– f) of thermal radiation wavelengths. The parameter f is taken to relate to the concentration of greenhouse gases present in the atmosphere.

- At a given latitude, the surface and the lower layer of the atmosphere are assumed to adjust their temperatures to ensure energy balance, so that the rate of energy entering and leaving match. For the upper layer of the atmosphere, energy balance is also assumed, but this requires integrating energy gained and lost over all latitudes, since air circulation is taken to maintain a uniform temperature for the upper layer of the atmosphere.

- Heat transfer between latitudes via atmospheric circulation is not fully modeled, but is addressed partially via the assumption that the temperature of the upper atmosphere is independent of latitude.

These assumptions vastly oversimplify the way Earth’s climate works. Yet, they include enough elements, and enough thermal physics, that perhaps some dynamics of the real system will be reproduced by the model.

The model is depicted below.

Figure 1

The surface receives energy from the Sun, more at the equator and less at the poles, and exchanges energy with the lower layer of the atmosphere, as well as radiating some energy directly to space. The lower and upper layers of the atmosphere also exchange energy, and the upper layer radiates energy to space.

At low latitudes (near the equator), surface heating leads to the adiabatic lapse rate being exceeded in a way that triggers convection.

In general, the zone where convection happens between the layers of the atmosphere may be different than the zone where convection happens between the surface and the lower layer of the atmosphere. (In a more complex variant of the TW model, these zones are more similar.)

That’s the TW model.

In what follows, I offer results for the dynamics of the model, based on model parameters as specified in the Appendix. Given those parameter values, I’ve numerically solved for the temperatures T₁(𝛳), T₂(𝛳), and T₃ and the energy flows that yield energy balance in steady-state.

Basic TW Model Predictions

For the model parameters I’ve considered, within the TW model temperatures vary with latitude as shown in the following figure.

Please keep in mind that I’m not expecting the TW model to accurately model Earth in any quantitative way. I’m just hoping to see some general qualitative similarities between dynamics of the model and some of the dynamics on Earth.

Figure 2

The figure shows how surface temperature (red curve) and the temperatures of the two layers of the atmosphere (green and blue curves) vary with latitude.

The surface temperature (red curve) rises as one moves from the polar region towards lower latitudes, until a latitude of 42º where a threshold temperature of 25.4℃ is achieved. After that threshold point, the surface temperature rises only very slowly, reaching 26.9℃ at the equator.

The surface temperature is very cold (-80℃) at the poles. This is because the TW model does not account for the air and ocean currents which warm Earth’s polar regions.

Averaging the surface temperature over the globe, the average surface temperature is 19.3℃, a little warmer than Earth. (In computing the average, latitudes nearer the equator are weighted more heavily than latitudes nearer the poles, because the surface has more area at lower latitudes.)

To understand why the temperature plot looks as it does, it helps to look at convective cooling effects, as shown below.

Figure 3

For latitudes below 52º, convection transports heat between the two layers of the atmosphere. For latitudes below 42º, surface convection transports heat into the atmosphere and forms clouds that reflect some of the incident shortwave radiation.

The onset of convection explains why the curve for surface temperature (in Figure 1) changes slope at these two threshold latitudes.

(On Earth, the threshold latitudes for the onset of major convection and ocean thunderstorms are closer to the equator than they are in the TW model for the parameters I’ve chosen. The oversimplifications in the TW model mean that one can choose only a few of Earth’s parameters to fit properly. I chose to roughly fit the insolation and mean surface temperature values for Earth, at the expense of allowing the threshold latitude to be significantly different than what is observed on Earth. I think this is ok, because I am interested in the qualitative behavior of the model, not the absolute value of any quantitative results.)

These cooling effects can also be plotted as a function of surface temperature, as shown below.

Figure 4

One can see that surface cooling increases rapidly for surface temperatures above 25.4℃. This seems qualitatively similar to what one sees in WE’s Figure 3. This offers reassurance that the TW model is reproducing some of the climate features that WE’s analysis relies upon.

Let’s look at another type of graph that WE uses.

Figure 5

This chart shows surface temperature as a function of total downwelling irradiance at the surface within the TW model. It is notable that the slope of the curve greatly flattens for irradiance values above about 450 W/m². This looks qualitatively quite similar to WE’s Figure 2, though the specific irradiance threshold value is different for the TW model and for the Earth.

In Figure 5, temperature increases monotonically with irradiance. This matches WE’s Figure 3 for land-based data, but differs from WE’s Figure 4 for ocean-based data. In the latter figure, temperature above the threshold declines somewhat with increasing surface irradiance.

Can the TW model account for such non-monotonic behavior?

It turns out that a variant of the TW model exhibits such behavior.

Figure 6

The simple form of the TW model uses the same adiabatic lapse rate, 𝚪, everywhere. In reality, the adiabatic lapse rate depends on the extent to which water vapor is present. For moist air, the lapse rate is smaller, and for dry air it is larger.

I would expect that the atmosphere is likely to be more humid where surface convection (presumed to be above an ocean) is happening, and less humid where there is no surface convection. So, the lapse rate for convection between the layers of the atmosphere ought to be larger when there is no surface convection, and smaller when there is surface convection. That’s the assumption used in the variant of the TW model that yields the temperature vs. irradiation curve in Figure 6.

In Figure 6, the temperature for a given irradiance drops as surface convection begins. This is qualitatively similar to what is observed in WE’s data for ocean locations.

Once again, I feel reassured that the predictions of the TW model qualitatively reproduce what WE has seen in data for Earth.

For the remainder of this essay, I’ll stick to the version of the TW model that yielded Figure 5, since that model is easier to understand.

Response to Greenhouse Gas Forcing

What does the TW model predict will happen if the concentration of greenhouse gases is increased?

Let’s consider a top-of-atmosphere (TOA) radiative forcing ∆F = 7.4 W/m², which I understand to be roughly the radiative forcing predicted to occur on Earth if the concentration of CO₂ was quadrupled.

As I understand climatologists’ use of the term, radiative forcing is a measure of the radiative imbalance that would occur at TOA if greenhouse gas concentrations were increased, but the atmosphere and surface were otherwise unchanged thermodynamically. I assume this means that all temperatures remain the same, as do convection and cloud coverage.

Based on this understanding, a TOA imbalance of 7.4 W/m² occurs in the TW model if the longwave absorption fraction, f, is increased from f = 0.600 to f = 0.631. So, to compute the effect of a TOA forcing ∆F = 7.4 W/m², I re-ran the TW model for f = 0.631, solving for the new temperatures, convective heat flows and cloud-induced albedo increases.

The old and new temperatures are shown below.

Figure 7

The mean global surface temperature in the TW model increases by 1.84℃.

Please don’t attach significance to this particular value. I don’t believe the absolute magnitude of this number to be meaningful, given the limitations of the TW model. What is likely to be meaningful, however, is how this value compares to other predictions of temperature change associated with the same model.

Checking WE’s Procedure for Predicting Response to Forcing

As I understand it, WE’s procedure for computing the Surface Response to Increased Forcing goes like this:

- For a given TOA radiative forcing value ∆Fₜ, compute an equivalent increase in downwelling surface irradiance, ∆Fₛ. In WE’s example, on Earth, a TOA forcing of ∆Fₜ=3.7 W/m² was thought to lead to a downwelling forcing 1.3 times as large (presumably leading to a ∆Fₛ=4.8 W/m² increase in downwelling radiation).

- Given a graph of surface temperature T₁ versus surface irradiance 𝚽, compute the derivative dT₁/d𝚽. (That graph might be WE’s Figure 3 or 4 or my Figure 5.)

- At each point on the planetary surface, compute the temperature change ∆T₁ as ∆T₁ = ∆Fₛ × (dT₁/d𝚽).

Let’s call this procedure Temperature-Irradiance Curve Following, or TICF. TICF might or might not be an accurate representation of the procedure that WE is advocating. He can let us know. Regardless, we can evaluate how well TICF works with respect to the TW model.

With regard to step #1 above, comparing the mean total (SW+LW) surface irradiance before and after applying the ∆Fₜ=7.4 W/m² TOA forcing (i.e., before and after increasing f from 0.600 to 0.631), the mean total surface irradiance increases by ∆Fₛ=12.15 W/m². (So, in this case ∆Fₛ=1.6 × ∆Fₜ.)

When I apply step #2 to my Figure 5, then apply step #3 using ∆Fₛ=12.15 W/m², and average over the surface of the planet, the TICF procedure predicts a mean global surface temperature change of 1.02℃. That’s 45 percent less than the “actual” mean temperature change value of 1.84℃ produced by the TW model.

So, the TICF procedure did not do a very good job of predicting temperature changes in the TW model.

Why Doesn’t TICF Predict Temperature Correctly?

The TICF procedure is appealing intuitively. So, why doesn’t it correctly predict temperature changes?

As far as I can tell, there are two ways in which the TICF procedure as I outlined it goes wrong.

One problem with TICF, as I’ve outlined it, is that the surface irradiance forcing ∆Fₛ is assumed to be a constant that is independent of latitude.

Let’s look at how the surface irradiance changes when the forcing is applied (i.e., when f =0.600 changes to f =0.631).

Figure 8

The red curve (∆ SW+LW) indicates the change in total irradiance absorbed by the surface, ∆𝚽. As one can see, this is nowhere near being a constant. It depends strongly on latitude, 𝛳.

Let’s assume we know ∆𝚽(𝛳), and try using this to predict temperature changes via the formula ∆T₁ = ∆𝚽(𝛳) × (dT₁/d𝚽). We could call this procedure Spatially-Varied-Forcing TICF, or SVF-TICF. (This procedure isn’t likely to very useful in practice, even if it works, because anyone who knows ∆𝚽(𝛳) probably also already knows the temperature change.)

How well does SVF-TICF predict temperature changes?

Figure 9

The chart above shows the change in surface temperature, as a function of latitude, as predicted by TICF, as predicted by SVF-TICF, and as in the actual solution of the TW model.

It’s apparent that the TICF procedure which assumes a constant forcing ∆Fₛ (green curve) matches the right answer (red curve) almost nowhere. It’s no wonder that its prediction of the change in mean surface temperature is way off.

What about SVF-TICF? For latitudes between 90º and 44º, the SVF-TICF predicted temperature (blue curve) change closely tracks the “Actual” temperature change within the TW model (red curve). So, that’s an improvement.

However, while it might be a little difficult to see in the chart, for latitudes between 44º and 0º, the TICF (green curve) and SVF-TICF (blue curve) predictions join together, and both predict tropical surface temperature increases much smaller than the “Actual” result (red curve).

Because a global average weights low latitudes strongly, the mean global surface temperature increase predicted by SVF-TICF is 1.05℃, just barely larger than the 1.02℃ predicted by TICF, and still much less than the actual increase of 1.84℃.

So, even with accurate information about spatial variations in the downwelling irradiance forcing, the TICF procedure fails to accurately predict temperature changes.

What is the core problem with TICF?

TICF depends on the assumption that the curve of surface temperature vs. surface irradiance is fixed, and that a “forcing” will simply cause different locations on the surface to change where they appear on this fixed curve.

So, the procedure is critically dependent on the temperature vs. irradiance curve not changing.

Unfortunately, the curve does change.

Figure 10

As seen in the chart above, the curve of surface temperature vs. total surface irradiance superficially looks mostly the same before and after the forcing is applied. But what is going on to the upper right? Let’s look at that part more closely.

Figure 11

Once total surface irradiance exceeds about 450 W/m², the “initial” and “final” curves are different. Unfortunately, this region of the graph applies to a majority of the surface area of the planet.

If a forcing raises the temperature of the upper atmosphere layer (as can be seen to happen in Figure 7), this increases the temperature at which tropical thunderstorms “cap” the surface temperature. This is what shifts the temperature vs. irradiance curve.

To generalize this result a bit, the temperature vs. irradiance curve in the TW model is unchanged by forcing in locations where energy transfer is entirely radiative, but the curve changes in locations where convection is important.

Since convection and atmospheric circulation are important, albeit to varying degrees, almost everywhere on Earth, it seems likely that the temperature vs. irradiance curve on Earth might shift in response to forcing.

Thus, the TICF procedure seems unlikely to be effective in accurately predicting surface temperature changes in response to forcing.

Do Tropical Clouds and Convection Moderate Warming?

WE has suggested that tropical cumulus cloud formation and thunderstorms (supporting strong convective heat flows) help to moderate Earth’s temperature.

Let’s see what the TW model has to say about this hypothesis.

I redid the temperature change calculation, holding some factors fixed. Once again, I assumed a 7.4 W/m² TOA forcing, modeled by increasing the longwave absorption fraction from f=0.600 to f=0.631. The results for the increase in mean global surface temperature were:

- 2.61℃: cloud albedo and convective heat transfer held fixed.

- 2.05℃: cloud albedo held fixed and convective heat transfer allowed to adjust.

- 1.84℃: cloud albedo and convective heat transfer both allowed to adjust.

So, if a researcher failed to account for increased cloud albedo, they would predict a temperature change 11 percent larger than what actually happens in the TW model. If a researcher failed to account for both increased cloud albedo and increased convection, they would predict a temperature change 42 percent larger than what actually happens.

(I have the impression that the GCM computer codes used by climatologists all model convection changes. Some reading suggests that GCM’s typically also model cloud. But, I’m not an expert on GCM’s and would rather not get into a debate about them. Let’s stick to talking about what the TW model tells us.)

(The TW model likely overestimates the cooling effect of clouds because the model accounts for increased reflection of sunlight from clouds, but does not account for increased longwave absorption and emission from clouds, which tend to have a warming effect. On Earth, on average, longwave warming by clouds compensates for about 60 percent of the shortwave cooling by clouds, although cooling effects predominate more strongly in the tropics, cf., WE Figure 2.)

The bottom line is that the hypothesis that “increases in tropical cloud formation and convection moderate planetary warming” is valid within the TW model.

Do Tropical Clouds and Convection Cap Warming?

The results of the TW model do not support the hypothesis that “tropical cloud formation and thunderstorms place a hard limit on planetary temperature increases.”

In the TW model, there is not an absolute “thermostat” effect that prevents tropical surface temperatures from increasing in response to a forcing. To the contrary, the temperature at the equator increased by 1.46℃ in response to the forcing.

What may be confusing is that there is a relative “thermostat” effect that prevents tropical surface temperatures from increasing too much, within the context of a given upper atmosphere layer temperature.

So, in the context of the baseline TW model, surface convection is triggered at a surface temperature of 25.4℃ at a latitude of 42º, and once convection is active temperature increases slowly to a maximum of 26.9℃ at the equator.

This might make it appear that there is a “thermostat” set at 25.4℃.

However, after the forcing is applied, surface convection is triggered at a surface temperature of 26.8℃ at a latitude of 43º, and once convection is active temperature increases slowly to a maximum of 28.3℃ at the equator.

So, there still appears to be a “thermostat”, but after the forcing, the thermostat is set 1.4℃ higher.

The reason it works this way is that the onset of surface convection is governed by the lapse rate and the temperature of the upper layer of the atmosphere. The forcing caused the temperature of the upper layer of the atmosphere to increase by 1.4℃. In the TW model, this leads to a corresponding increase in the “maximum surface temperature” in low latitudes.

The lesson to be learned from this is that, within the TW model, tropical thunderstorms cap the maximum surface temperature, but only relative to the temperature of the upper atmosphere layer. If the temperature of the upper atmosphere layer (i.e., the upper troposphere) increases as a result of forcing, then the temperature limit enforced by tropical thunderstorms will increase as well.

Relating the TW Model to Earth

How does the TW model relate to Earth?

The TW model certain leaves out many processes which are important in Earth’s climate. Earth’s atmosphere includes many layers, and is affected by global circulation patterns in the atmosphere and oceans, circulation patterns which are largely unaccounted for in the TW model. The radiative dynamics in Earth’s atmosphere are also more complex than those assumed in the TW model.

The parameters used in the TW model example I’ve presented lead to behavior that matches Earth in some ways (e.g., insolation and global temperature are at least vaguely comparable in the TW example and on Earth) but not in others (e.g., strong convection occurs over a broader range of latitudes in the TW example than on Earth). The simplifications in the TW model mean that its behavior can’t be quantitatively matched to that of Earth except in a few respects.

Yet, the TW model includes the dynamics of the onset of convection in a way that seems likely to be at least somewhat relevant to the way things work on Earth. Both in the TW model and on Earth, convection is stimulated when surface warming causes the adiabatic lapse rate to be exceeded. This creates a threshold effect that is relative to the temperature of the upper troposphere.

I think the TW model is accurate in portraying this aspect of climate physics.

Conclusions

Based on working with the Thunderstorm World model, it seems that:

- It makes sense to be skeptical about the ability of the TICF procedure to accurately predict how surface temperatures would respond to forcing.

- Tropical cumulus clouds and convection associated with thunderstorms likely moderate planetary temperature changes, but aren’t likely to provide any fixed limit on planetary warming.

APPENDIX: Model Details

At a given latitude, 𝜽, the net energy flows within the Thunderstorm World (TW) model are as depicted in the following illustration.

Figure 12

For the calculations presented in this essay, the following parameter values were used:

- Mean insolation, Sₐ = 292.6 W/m². (This is approximately the insolation Earth experiences, if non-cloud albedo is taken into account.)

- Convection adiabatic lapse threshold, 𝚪H = 30 Kelvin.

- Convection strength, Z = 0.2 /Kelvin.

- Convection reference power, Sᵣ = Sₐ.

- Convection heat-transfer vs. cloud-formation fraction, 𝝌 = 0.7.

- Long-wave radiation absorption fraction, f = 0.6 (prior to added forcing).

The area-weighted global average of a quantity g(𝜽) is given by the integral from −𝜋/2 to 𝜋/2 of ½⋅cos(𝜽)⋅g(𝜽).

For the variable-water-vapor model variant used to generate Figure 6, the adiabatic lapse threshold 𝚪₂H for convection between the lower and upper atmosphere layers is made to transition from 33 K to 30 K as surface convection begins. (In particular, this transition is made as the value of T₁’ − T₂’ − 𝚪₁H transitions from -1 K to 1 K, where T₁’ and T₂’ are the values that T₁ and T₂ would have if only radiative heat flows were present, and where 𝚪₁H = 30 K. This slightly odd recipe was chosen because it was found to support numerical convergence.)

Interesting reading, Dr Bob Wentworth,

I find your approach to producing some mathematical structure to the ideas of WE very interesting. The fact that some resemblace to the experimental data is found is profound since some of the hypothesis seem to be set up to provide the worst case for the theory to replicate WE conditions.

1) Rapid rotating planet: the proposed mechanism has a great day-night cyclic component.

2) Uniform temperature at the TOA: the whole finding that the curve surface temperature vs irradiance is not constant is tied to this temperature rising in the tropics, maybe it doesn’t rise uniformly but more in the poles and less in the tropic? I really don’t know. I assume it is most probably not uniform.

3) Assuming that convection is simply proportional to the lapse rate when water vapor variations are at least as important, and tend to increase the cooling effect of the storm.

Relating to my point 2. you claim statement “T₃, is the same at all latitudes. (On Earth, the average temperature in the upper troposphere at a pressure of 190 mbar is only weakly dependent on latitude, so this assumption of constant temperature isn’t unreasonable.)”. From your link it seems it varies from -60ºC to -55ºC that is quite a lot since the expected increase by quadrupling the CO2 is almost 2ºC.

“That’s 45 percent less than the “actual” mean temperature change value of 1.84℃ produced by the TW model.” … That’s better that the IPPC 3+-1.5ºC climate sentitivity.

Thank you for your effort.

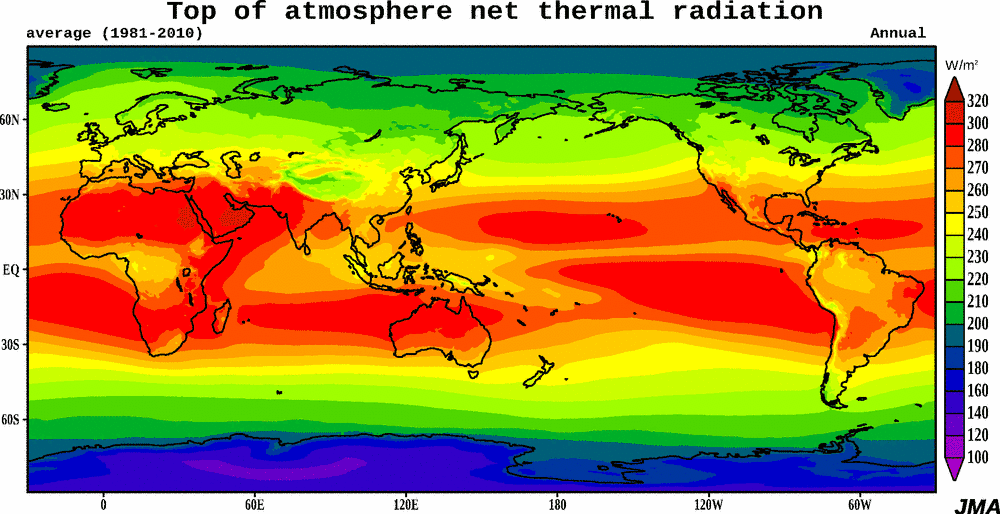

Here’s the oddity about global ocean temperatures that I was talking about.

Unless Bob’s modeled ocean temperature is something like this, I fear he’s looking at modelworld and not the real world.

w.

I wouldn’t put too much stock in Mr Wentworth’s analyses. The pattern he shows is that he believes he will find some truth in thought experiments (his imagination) which he puts into equations based on old textbook theory (with particular bias towards radiative principles). With this he is talented. However he is closed to novel ideas and observations, and alternative viewpoints (ego). You appear to come at the problem from first hand experiences in the field and data analysis. Both approaches have merit. There must be some happy medium and collaboration possible, but most of us appear to be stuck in our own lanes.

Exactly the point I was making, not sure Bob W spends too much time verifying and or validating his models, he seems to churn them out pretty quickly without to much concern for their actual usefulness or accuracy.

Willis on the other hand has spent years building his theory on one observation after another, one piece at time in front of everyone here taking on all comers and commentators. A careful process of verification and validation, what a serious person does.

You seem to misunderstand the purpose of these models.

The intention is to provide vehicles for understanding how physics connects to climate processes at a qualitative level.

I spend plenty of time verifying the internal correctness of my models. (The model reported here involved a high level of effort, including a lot of verification of internal consistency.)

But, validating against external data is not particularly relevant to the purpose of these models.

To my mind, a careful process of verification and validation includes connecting to underlying physics.

In the absence of such a connection being done explicitly, there is almost always an implicit mental model of how things are connected, and it’s very easy for such an implicit mental model to be internally inconsistent, or even provably false.

My focus is on trying to surface and examine those sort of implicit assumptions.

Simple models provide a way of examining, and validating or invalidating, such implicit assumptions.

There is no “particular bias towards radiative principles.” I have a bias towards including components that are known to be important to a particular issue being discussed. Often, when it comes to atmospheric physics, that includes radiation.

It only seems like a bias relative to some people’s inclination to pretend radiative physics doesn’t exist.

With respect, I believe I’ve demonstrated that I’m interested in novel ideas and I’m willing to have my mind changed about things.

What I am not so receptive to are assertions that flat out violate well-established physics that has been known for 200 years and is used in multiple fields of engineering on a daily basis.

Some commentators routinely make such assertions and do not themselves seem to be open to considering the possibility that they might have gotten something wrong.

“I have a bias towards including components that are known to be important to a particular issue being discussed.”

It is not uncommon in climate science to dismiss anything other than radiative components. Many have a belief that because gases have certain known radiative properties it must therefore be the key to any observed changes in the atmosphere. This is a type circular reasoning that has led the field to spinning its wheels for decades. It will never lead to any advancement. I imagine it is some sort of Einstein complex where everyone assumes physicists know everything. Textbook theories are tested and valid within a certain context but there remains little evidence of how this relates to the Earth system. Back in the real world you will find meteorologists are often the biggest skeptics on commonly accepted climate theories. The refusal of radiative physicists to think outside their own field indicates some commonality that must relate to ego. It has been demonstrated countless times that the fundamental GCM equations simply are not adequately describing the system. The GCMs propagate uncertainty that is way outside the realm of physical possibility. Willis offers some observations of meteorological phenomenon which are clearly omitted in the ever increasing GCM temperature projections. He may not have the training to communicate this in a way that fits with your preferences; however, the automatic dismissal of arguments that are not communicated with mathematical formulations is your issue. It might be hard to hear that physicists can learn much from regular folk. In the end it will likely be fruitless to conceptualise the system as finite layers and elements in mathematical computations. It may, however, be possible to model some bounds on the system using a whole suite of assumptions. Those who reach the highest levels of intellect understand that even illiterate children may have perspectives, insights, and a certain wisdom that we can learn from. Those who dismiss them only wish to protect their own sense of self-importance.

I’m sorry you’ve had that experience, which I imagine would be frustrating.

Personally, I’ve never witnessed that happening. What I’ve witnessed is people dismissing the relevance of radiative phenomena, and people objecting to those phenomena being dismissed.

Convection and radiation are clearly both relevant to climate.

However, the interface between Earth and space involves only radiative phenomena. And, there are some basic principles of physics that establish that radiative phenomena and greenhouse gases MUST play a role in warming the planet. Though, some aspects of the size of the effect that are open to legitimate debate.

I find it bizarre how often climate skeptics characterize anything that includes radiation at all as overemphasizing radiative physics.

That would be circular reasoning.

But, that’s not an accurate reflection of any reasoning I’ve ever heard from a climate scientist.

I don’t know a single physicist who assumes that.

I think most physicists are acutely aware of there being a dividing line between what is known and what isn’t known, and are aware that there is a lot we don’t know.

But, physics is somewhat special in terms of how definitively some things are known, within the realms where things are known. Physicists can sometimes predict something to 10 significant digits, where in other fields people are sometimes lucky to get something to within 10 percent.

There are principles of physics which have been proven on a daily basis for a hundred or more years, without any exception being discovered, ever.

There are things in physics that are as certain as 1 + 1 = 2.

That doesn’t mean physicists know everything. But, sometimes someone says something that, to a physicist, is equivalent to hearing a claim that 1 + 1 = 73. And, in those cases, a physicist is likely to say, with a lot of justification, “that can’t be right.”

Basic principles of physics have been shown to be valid in every context that has been considered.

It’s true that there are uncertainties about aspects of how it all applies to complex systems. But, there are clear parts and unclear parts.

I know there are plenty of things I don’t know. I’m interested in learning about those. I just get upset when people claim the equivalent of 1 + 1 = 73 and expect me to just accept that, when I have good reason for saying “that can’t be right.”

That may well be true, from what I’ve seen.

But, frankly, I’ve encountered meteorologists who seem stunningly ignorant about physics. And, weather and climate are not the same thing.

I’d have a lot of respect for a meteorologist who was also really knowledgeable about physics and climate. But, if not… I’m not sure what meaning I should take away from some meteorologists being skeptical.

Willis has been offering interesting observations of meteorological phenomena. But, I’ve seen no evidence being offered that these phenomena are “omitted in the ever increasing GCM temperature projections.”

There seems to be an assumption that these are being omitted.

I’m curious if that’s actually true.

My simple-minded Thunderstorm World model reproduces many of the phenomena that Willis seems to consider “surprising.” So, I’m certain that many of those phenomena are also included in fancier climate models.

I’m sorry it seems that way.

I’m pretty sure that’s not actually what I’m doing.

I might question arguments that are presented without math. But, I only dismiss them when the math says with clarity that the argument is wrong.

Sometimes the math says someone else is wrong. Sometimes it says I’m wrong (and I’ve owned up to it when that has happened). And, sometimes the math is inconclusive.

In Willis’s case, so far my assessment is mixed. The math says (1) he’s probably right that thunderstorms moderate global warming, (2) the type of analysis he offered in one of his essays is almost certainly mathematically wrong, but (3) his main hypothesis is still an open question—there isn’t yet enough evidence to decide either way.

Willis presents a really interesting hypothesis, and I have no interest in passing judgment prematurely. I don’t know the answer, and I accept that I don’t know. I’m interested in learning more. This essay was a step in that process.

It’s not hard to hear. I’m delighted when I can learn things from others.

I’ve learned some interesting things in the comments responding to this essay, and I appreciate that.

Part of the discipline of physics is learning to be discerning about what simple models can teach us something, or allow us to place “some bounds” on what could be going on.

I’m sorry if you don’t get much out of it. And, I think that the right simple models do have valuable things to teach us.

I totally honor that. For what it’s worth, I co-founded a camp for parents and children dedicated to treating young people with deep respect. (The camp spread to five states and has been running for over a decade.) I’ve coached parents to pay more attention to what their children have to say, and some kids have told me they had almost never been listened to before.

So, you’re “preaching to the choir.”

And, I get that this applies not just to children, but to all human beings.

I’ve taught workshops on “connecting across differences” and “listening to people you’re tempted to dismiss.”

I don’t claim to be perfect at doing these things, but you’re talking about things that are deeply important to me.

And… it still makes sense to be discerning about what we do with what we hear.

If a kid has a scrambled idea of how the world works, I’ll be curious about what those beliefs mean to them. But, I’m not necessarily going to accept what they theorize about the world as the “truth.” I’m going to compare what they say to what I know and what I don’t know, and think about what I’m hearing.

I’ll almost certainly learn something from having the conversation. But, I won’t always end up agreeing with all the beliefs that the other person is sharing with me.

We each know things. I want to combine and integrate what we know, to form a more complete picture of reality.

I’m happy to learn new things. And, I’d love it if others too would be willing to figure out how to integrate and reconcile what we each know.

I’m interested in what others know, e.g., as a meteorologist. And, I’d like them to be willing to be interested in what I know as a physicist. If there’s a conflict in what we think we know, let’s talk it through.

Great response. I’ve come to look forward to your articles and comments on this page. There are too few forums for healthy respectful debate on these issues.

“But, I’ve seen no evidence being offered that these phenomena are “omitted in the ever increasing GCM temperature projections.”

There seems to be an assumption that these are being omitted.

I’m curious if that’s actually true.”

Boiling things down through all their complexity current generation GCMs still output a global average ECS range (or transient response) that can be calculated on the back of a napkin by radiative forcing alone. Nothing has changed for decades. Keen observers are pointing out that something is clearly missing – this is where the most interesting discussions are happening, albeit too far and few in between.

I seek to encourage collaboration between disciplines and allow assumptions that fall outside the UNFCC framework. Outside engineering physics is interesting for natural scientific curiosity. For policy empirical observational findings must take precedent. I understand it is inconvenient politically to acknowledge the radiative forced models are not really matching observations, particularly when an illusionary/fabricated consensus has been presented. Ongoing accurate honest observations will give rise to the need for new hypotheses. The brainstorming happening now is only the beginning.

Forgive me if I seem dumb Willis, but what is this “frequency” you plot on the Y axis of your graph? Frequency of what, over what area of the globe, and in what units?

Sorry for the lack of clarity. It’s the count of the number of gridcells in each temperature interval.

w.

The TW model’s plot of frequency vs. surface temperature shows a spike in frequency at the upper end of the temperature range, per the attached plot.

(The extremity of the frequency spike in the model reflects how high a value of the “convection strength” parameter I had used in my calculations.)

Is that what you were looking for to validate the model, or were you looking for something else?

Bob W,

Willis and I have mused occasionally in the past whether the temperature control acts by a difference from a reference value of temperature, as does many a thermostat device. We or I at least have had problems deciding if this is indeed the case; and if it is the case, what is that reference or set temperature and how is it formed?

You have written “convection is stimulated when surface warming causes the adiabatic lapse rate to be exceeded. This creates a threshold effect that is relative to the temperature of the upper troposphere.”

Am I correct to infer that you consider the upper troposphere T to be that reference temperature? If yes, then what sets that temperature? Is is related entirely or largely to the lapse rate at a given earth point? What would drive it towards constancy? Is there constancy in the short term like diurnal, or seasonal or annual or decadal or more? Can it be regarded as a type of reference value to which several other temperatures can be compared when one is seeking to explain mechanisms?

Thank you Geoff S

Most of the the thermal physics involved depends only on relative temperatures. So, it seems likely that any “set point” would depend on some relative temperature.

This seems to me to be the most likely candidate for a reference temperature, and it certainly is the reference temperature that emerges as important in the TW model.

Ultimately, it’s an emergent property of the entire system.

In places and at times where strong convection is present, the surface temperature and the temperature of the upper troposphere will inevitably be connected via the lapse rate.

But, overall, the temperature of the upper troposphere will be determined by energy balance of the system as a whole.

Factors like insolation, GHG concentration, and everything else in the climate system all affect this temperature. But, radiative balance is an essential factor.

It might require more investigate to be certain about why it’s as stable as it is, and exactly how stable it is… I referenced a source that averages temperatures over a year or more.

I imagine that atmospheric circulatory patterns (convection cells at different latitudes) are a primary factor leading to weak latitude-dependency in this temperature.

Note that the results of the TW model don’t really depend on the temperature being entirely latitude independent; it may be mostly the temperature of the upper troposphere in the zone where convection starts to happen that acts as a reference temperature.

At the upper troposphere, I wonder if radiative warming from the stratosphere (with its ozone-driven absorption of sunlight) might also play a role in stabilizing the temperature.

As far as temporal stability, I don’t have information on that, as yet.

Maybe? Seems plausible.

Glad that you got on to this thread after the invective cooled down and the trolls lost interest. It seems wise. I appreciated the work, and some others did attempt to IMO faithfully explain parts that I had trouble with. I think I understand what you and Willis are trying to do, and I look forward to future work on this model and this topic in general. Thanks.

Maybe for the best, but it wasn’t intentional. I had gotten used to being notified when a post of mine was going to be published, and it didn’t happen this time around. My attention was elsewhere, and I didn’t know the reactions were rolling in.

Thanks!

Thanks, Bob. Consider this movie. It shows cloud top altitude as a proxy for deep convective thunderstorms.

Does it seem like the thunderstorms are forming in response to SSTs? ‘Cause it sure looks that way to me.

w.

PS—As far as I know, you still haven’t answered my question … here it is again.

Well, I partially answered in in a comment in response to your comment, but my comment got stuck in moderation. I’m not quite sure how that works? Maybe you can find it and free it up?

I’ll take a look … nope, the moderation list is empty. No clue what happened.

w.

Well, as I mentioned the last time you pointed me to this movie, nothing about the movie provides any indication as to whether the surface temperature threshold for deep convective thunderstorms relates to an absolute temperature threshold or a relative temperature threshold.

The TW model suggests that the threshold could be relative to the temperature of the upper troposphere, a temperature which could shift as a result of a climate forcing (and which does shift in the TW model).

My answers, here and here, appear to have emerged from moderation.

Bob, I pointed out a study saying that the temperature of the WPWP has been stable for over a million years …

Next, the movie shows that the SST threshold for deep convection is the same every month. So unless your claim is that the temperature of the upper troposphere moves in exact lockstep with the surface temperature over the course of the year, it seems to be an absolute rather than a relative threshold.

This is borne out by the following movie. It’s like the previous one, but the previous one was monthly averages. This is the actual month-by-month data. You can see that every month is different, sometimes very different … but the thunderstorms slavishly follow the SST.

w.

I’ve responded to the observation here and here.

I agree that it could be evidence to support the hypothesis of an absolute temperature threshold. But, it would be stronger evidence if you could show that existing models for understanding climate wouldn’t have predicted that.

As I understand it, you are fundamentally hypothesizing that there are important emergent processes that regulate Earth’s temperature in ways that are not properly accounted for via existing understandings of climate.

It pretty much needs to be the case that this is what you are hypothesizing, because you are trying to argue that there is something wrong with the predictions of existing climate models. If you’re just pointing out some detailed phenomena that are entirely consistent with existing climate models, you wouldn’t get to make this sort of argument.

You can only demonstrate that hypothesis if you offer evidence for some phenomenon existing and ALSO demonstrate that existing understandings of climate would do not account for those phenomena.

It seems to me that you keep addressing the first piece (evidence consistent with the phenomenon you assert exists) without giving much attention to the second piece (establishing that these phenomena are not already accounted for in the existing understanding of climate).

You appear to be merely assuming that existing understandings of climate can’t explain these phenomena. That’s making your case by assumption, not via evidence.

There is no need for the temperature of the upper troposphere move in lockstep with the surface temperature. (In fact, the whole relative temperature threshold would break down if high altitude and surface temperatures tracked too closely.) What would suffice is for the temperature of the upper troposphere to be relatively stable, in areas that are marginal for the initiation of thunderstorms.

For example, if the upper troposphere temperature was stable throughout the tropics, not varying by more than half a degree or so (when averaged over periods of a week or so), that would produce the observed behavior based on a relative-temperature thunderstorm threshold.

Or, it would be okay if the temperature at a given location varied somewhat by season, so long as the warmer temperatures in the upper troposphere moved a bit southward in the boreal (Northern Hemisphere) winter and a bit northward in the boreal summer.

(I’ve found a source that does say there is some seasonal temperature variation in the tropical upper troposphere, but that doesn’t rule out the second option that I listed.)

* * *

I don’t think you and I agree about where the “burden of proof” lies.

If you are claiming a dependence on absolute rather than relative temperature, you are making somewhat of an extraordinary claim, to the extent that many of the physical processes involved depend only on relative temperatures.

To the extent that that’s true, the burden would be on you to show that relative temperatures can’t explain what you’re seeing. (Though, I’ll acknowledge that there are some processes which may depend on absolute temperature, so I’m not on rock-solid ground.)

But, more to the point, I think you’re ultimately trying to argue that existing climate models are incomplete in an important way.

That’s an extraordinary claim that requires extraordinary proof. It’s not good enough to just suspect that existing climate models wouldn’t predict what you think you’re seeing. You’ve got to really show that, or you’re not establishing that existing models aren’t complete.

* * *

By the way, I noticed you haven’t responded (as far as I can tell) to the assertion that my model invalidates your process for predicting the way surface temperature responds to increased forcing.

Bob, thanks much for your thoughtful post. In particular I hadn’t deeply considered your following point:

I’ll need to give that question some solid consideration and investigation.

Best regards,

w.

PS—I was unaware that my process “predicts the way surface temperature responds to increased forcing”. I don’t recall making any predictions so I’m not clear what you’re referring to.

I’m referring to the content of your essay Surface Response to Increased Forcing. In that essay, you seem to be trying to predict how surface temperatures would change in response to a forcing associated with increased CO₂ doubling.

You conclude “An increase of 3.7 W/m2 in downwelling surface radiation, which is the theoretical increase from a doubling of CO2, will only increase the surface temperature by something on the order of a half of a degree C.” [I realize you belatedly made a distinction between TOA changes and surface changes; I’m not worried about that hiccup.] Your statement is a prediction about the way that “surface temperature responds to increased forcing.”

The worlds “will only increase…” are indicative of a prediction.

You may think your conclusion is rooted in observation, but you have used assumptions about the implications of observations in reaching that conclusion. You have applied a predictive procedure, inspired by observations. The result itself is not an observation; it’s a prediction.

In my essay above (beginning in the section “Checking WE’s Procedure for Predicting Response to Forcing”), I examine what would happen if your method of analysis was applied to my TW model.

I show that your method of analysis produces incorrect results, regarding the behavior of the model.

I examine why the procedure produced incorrect results. The reasons the procedure goes wrong are reasons that we can expect will also apply in the case of Earth’s climate. So, the method does not seem to be a trustworthy way of predicting the behavior of Earth’s climate in response to forcings.

Does that make any sense to you?

* * *

I noticed a semantic issue in your essay which might be nothing or might indicate a significant gap in understanding.

You seem to refer to the total downwelling radiation as surface “forcing.” That’s an unconventional usage. “Forcing” conventionally refers only to externally-caused changes relative to a baseline, not to any baseline levels. So, technically, downwelling surface radiation is not “forcing”; only changes to downwelling surface radiation could be termed “forcing.”

That’s arguably just a pedantic matter of terminology. Maybe it’s not important.

But, I wonder if imprecise use of terms might contribute to some imprecise logic that I perceive as being present in your analysis.

You might see if you can follow the logic in my essay as I work through my version of your analysis (which I call TICF).

I’m glad that point was helpful. I think it’s important to address if you’re going to make a convincing case for the concerns you are raising.

Some of the observations that you find surprising are, I think, easily explained by conventional understandings of climate.

While my TW model can’t necessarily account for all the observations you find surprising (e.g., the long-term stability of the WPWP), I think my TW model demonstrates that at least some of the behaviors that you found surprising in the observations of data from Earth can be explained in ways that are already incorporated into current understandings of climate.

(Out of curiosity, did the graph of frequency vs. surface temperature from my TW model more or less show what you were thinking a model would need to show?)

Warmly,

Bob

All the clouds and vapor reduces the OLR and sending a lot of LW to the surface, keeping it warm. (LW is ~2*SW) It’s a loop. You can’t say one is causing the other.

Their fig.1 shows 26 to 30 deg C variation. Wouldn’t call that stable.

Thank you, Bob,

I appreciate the time you spent responding.

Now I shall be quiet for a while because all this needs some contemplation. Geoff S

We had a thunderstorm where I live a couple of days ago, it got very dark and cold and it hammered down with rain for many hours. It is ok to use models to think about something but most climate scientists use models to stop people thinking about the complex Earth processes and accept their views without question.