Guest Post by Willis Eschenbach

Eleven years ago I published a post here on Watts Up With That entitled “The Thermostat Hypothesis“. About a year after the post, the journal Energy and Environment published my rewrite of the post entitled “THE THUNDERSTORM THERMOSTAT HYPOTHESIS: HOW CLOUDS AND THUNDERSTORMS CONTROL THE EARTH’S TEMPERATURE“.

When I started studying the climate, what I found surprising was not the warming. For me, the oddity was how stable the temperature of the earth has been. The system is ruled by nothing more substantial than wind, wave, and cloud. All of these are changing on both long and short time cycles all of the time. In addition, the surface temperature is running some thirty degrees C or more warmer than would be expected given the strength of the sun.

Despite that, the earth’s temperature has stayed in a surprisingly narrow range. The HadCRUT global surface temperature shows that the range of the temperature trend was 13.9°C ± 0.3°C over the entire 20th Century. This represents a temperature variation of ±0.1% during a hundred years. That stability was the curiosity of curiosities for me, because to me that temperature stability was clear evidence of some kind of a strong thermoregulatory system. But where and what was the regulating mechanism?

The short version of my hypothesis is that a variety of emergent phenomena operate in an overlapping fashion to keep the earth’s temperature stable beyond expectations. These phenomena include tropical cumulus clouds, thunderstorms, dust devils, squall lines, tornadoes, the La Nina pump moving warm water to the Poles, tropical cyclones, and the Julian-Madden, Pacific Decadal and North Atlantic Oscillations. In addition, I’ve adduced a large body of evidence supporting my hypothesis.

So I was interested to see Judith Curry, in her marvelous weekly post entitled “Week in review – science edition“, had linked to a paper I’d never seen. It’s a paper from 2010 by Marat F. Khairoutdinov and Kerry A. Emanuel (hereinafter K&E) entitled AGGREGATED CONVECTION AND THE REGULATION OF TROPICAL CLIMATE, available here. Inter alia they say:

Moist convection in the Earth’s atmosphere is mostly composed of relatively small convective clouds that are typically a few kilometers in horizontal dimension (Byers and Braham, 1948, Malkus, 1954). These often merge into bigger clusters of ~10 km in horizontal dimension, such as air-mass showers. More rarely, under special circumstances, moist convection is organized on even larger scales; this includes squall lines (e.g. Houze, 1977), mesoscale convective complexes, (e.g. Maddox, 1980), and tropical cyclones.

…

One of the robust characteristics of self-aggregation is the rather dramatic change in the mean state that accompanies it. In particular, in all non-rotating experiments (Bretherton et al., 2005) and an experiment on an f-plane (Nolan et al., 2007), self-aggregation leads to dramatic drying of the domain-averaged environment above the boundary layer. This appears to be the result of more efficient precipitation within the convective clump as more of the condensed water falls out as rain and less is detrained to the environment, per unit updraft mass flux. Such dramatic drying would reduce the greenhouse effect associated with the water vapor, and thus, would lead to cooling of the SST, which in turn may disaggregate convection. This would re-moisten the atmosphere, increasing the water-vapor greenhouse effect, and, consequently, warming the system. So, as in self-organized criticality (SOC), the tropical state would be attracted to the transition critical state between the aggregated and disaggregated states.

Let me point out a few things about their most interesting study. First, they are clear that a strong effect of the aggregated thunderstorms is to regulate the tropical temperature … just as I’ve been saying for years.

Unfortunately, their study is model-based. This is always frustrating to me because there is no way to check either the quality of their models or how many runs ended up on the cutting room floor …

However, given that shortcoming, their study points to something I noted in my original post—not just aggregated thunderstorms but also individual thunderstorms dry out the air in between them. This has two big cooling effects on the surface.

First, the dry descending air allows for increased evaporation from the surface, because the dry air can pick up more moisture from the surface. This increased evaporation cools the surface.

In addition to the increased evaporation, the effect they discussed is that the dryer air descending around the thunderstorms reduces the amount of the world’s main greenhouse gas, water vapor, that is between the surface and outer space. This allows the surface to radiate more freely to space, which also tends to cool the surface.

In their summary they say:

Idealized simulations of radiative-convective equilibrium suggest that the tropical atmosphere may have at least two stable equilibrium states or phases, one is convection that is random in time and space, and the second is the spontaneously aggregated convection. In this study, we have demonstrated using a simplified and full-physics cloud-system-resolving models that there is an abrupt phase transition between these two equilibrium states depending on the surface temperature, with higher SST being conducive to the aggregation. A significant drying of the free troposphere and consequent reduction of the greenhouse effect accompany self-aggregation; thus, the sea-surface temperature in the aggregated state tends to fall until convection is forced to disaggregate.

So, big credit to them for noticing the thermostatic effect in the tropics. However, their look is tightly focused. They have looked only at one cooling mechanism. In addition, they have only looked at two of what are at least four of what they call stable equilibrium states or phases. However, again to their credit they’ve said “at least” two stable states, acknowledging the existence of others.

Since Khairoutdinov and Emanuel had demonstrated using models that dry air increased with increasing aggregated thunderstorms, I thought I’d take a look at, you know … observations. Data. Crazy, I know, since so much attention is paid to models, but I’ve been a computer programmer far too long to put much faith in models.

STABLE STATES

Let me start by saying that they are looking at the third and fourth stable equilibrium states in the entire spectrum of the daily tropical thermally-driven threshold-based atmospheric response to increasing surface temperature. Each of these steps involves self-organized criticality.

In the tropics, by dawn, particularly over the ocean, the night-time atmosphere is generally stable and thermally stratified, with clear skies at dawn.

The first step is when the solar warming of the surface warms the air above it enough to initiate the stable equilibrium state called Rayleigh-Benard convection. As is common with such self-organized transitions, once the critical transition temperature is exceeded, the change between states is rapid.

Once Rayleigh-Benard circulation is established, areas of ascending air are interspersed with areas of descending air. The areas of rising air, often called “thermals”, transfer surface heat and surface water vapor upwards. This cools the surface directly through conduction, because the air traveling across the surface picks up heat from the surface. The R-B circulation also increases thermal radiation to space from the upward movement of the warm air above the lowest atmosphere, which contains the greatest amount of greenhouse gases.

Finally, the R-B circulation increases evaporation by moving the surface moisture upwards and mixing some of it into the lowest part of the troposphere. This transition to R-B circulation is generally invisible, although the onset of daily overturning can sometimes be felt in the wind.

The second transition is again temperature-based. It occurs when the surface temperature is large enough to drive the Rayleigh-Benard circulation higher into the troposphere. In the tropics, this transition typically happens in the late morning. When the water vapor in the ascending columns of the Rayleigh-Bernard circulation is moved upwards to the “LCL”, the “lifting condensation level” where water vapor condenses, at that altitude cumulus clouds form. The water vapor in the air condenses into the familiar puffy cotton-ball cumulus clouds. Each individual cumulus cloud group sits like a flag marking an ascending part of the Rayleigh-Benard circulation shown above.

Again, the transition is rapid. In the space of about a half-hour, the entire tropical atmospheric horizon to horizon can go from clear air to a fully developed cumulus field. And again, the transition is temperature-based. Below a certain temperature, there are hardly any cumulus clouds at all. Above that temperature, suddenly there are lots of cumulus clouds.

The third transition occurs when a somewhat higher temperature threshold is exceeded. The third stage of development is when individual cumulus clouds self-aggregate into scattered cumulonimbus. They build tall cloud towers, and the rain starts.

After this transition to the thunderstorm state, large areas of descending dry air form around each thunderstorm. This is the return path of the air that was first stripped of water in the base of the thunderstorm. When the water vapor condenses it gives up heat. The heated air then moves up the thunderstorm tower, emerges at the top, and descends as dry air in the areas around the thunderstorm.

This stage, of active thunderstorms, is well illustrated in the most entrancing simulation shown below. The colored layer added at one minute twenty seconds shows the temperature of that layer, with dark blue being coldest and red/orange being warmest.

The fourth and final transition occurs only in certain conditions at the highest transition temperature, when individual thunderstorms self-aggregate into squall lines and supercells, medium-scale convective complexes, and tropical cyclones. This is the only one of the four stable equilibrium states studied by Khairoutdinov and Emanuel. As with the other transitions, they point out that it is associated with a transition temperature. Like the thunderstorm regime, areas of descending dry air form around the aggregated phenomena. Here’s a photo of a single squall line from space.

It is worth noting that each of these succeeding stages exhibits an increase in the rate at which the surface loses heat. With each transition, the rate of surface heat loss increases from a variety of causes. The cause that is discussed by K&E, increased radiation to space through drier air, is only one among many.

The first transition, from quiescent stratified night-time atmosphere to Rayleigh-Benard circulation, increases surface heat loss to the atmosphere through conduction and convection of both latent and sensible heat. It encourages atmospheric loss to space by moving the surface heat up above the lowest atmospheric levels with their denser concentration of the greenhouse gases, mostly water vapor and CO2. It mixes surface heat and surface water vapor upwards. Because water vapor is lighter than air, the ascending areas are moister and the descending areas are dryer in the R-B circulation.

The second transition, to the cumulus field, adds two new methods of cooling the surface. First, energy is moved from the surface aloft in the form of latent heat. This heat is released when the rising columns of air condense into clouds. The sun then re-evaporates the water from the upper surface of the clouds, and the water vapor mixes upwards. This moves the surface heat well up into the lower troposphere.

The cumulus field also cools the surface by reflecting sunlight back to space. This is a very large change in the energy balance, on the order of a couple of hundred watts per square metre or so. The timing and density of the emergence of the cumulus field is one of the major thermal regulation mechanisms. How strong is this regulatory action? Here’s a typical day’s available solar energy, measured at ten-minute intervals at a TAO buoy in the Equatorial Pacific Ocean.

The deep notch in the available solar energy from clouds covering the sun at around 11:30 AM in the graphic above is quite typical of the drop when clouds cover the sun. On this day it lasted about half an hour. It reduced the available solar energy flux by about six watts per square metre averaged over that 24 hour period.

By comparison, a theoretical doubling of CO2 from the present, which is highly unlikely to happen, would add a flux of about 3.7 watts per square metre during that 24 hour period.

So in that area, that one cloud would be more than enough to cancel out even a doubling of CO2 for that day … and that is just one of the many ways the surface is being cooled by emergent phenomena.

The third transition, from developed cumulus field to scattered thunderstorms, adds the whole range of new surface cooling methods that I list in the endnotes. And unlike the first two transitions, thunderstorms can actually cool the surface to a temperature below the temperature needed to initiate the thunderstorms. This allows thunderstorms to maintain surface temperatures. When any location gets hot a thunderstorm forms and cools the surface back down, not just to where it started, but down below the onset temperature. This “overshoot” is the signature of a governor as opposed to a simple linear or similar feedback. Simple feedback can only reduce a warming tendency. A governor, on the other hand, can turn warming into cooling.

In the fourth transition, the transition to the larger self-aggregated phenomena like squall lines, supercells, and the like, no new surface cooling methods are added. What happens instead is that the previous methods move to a new level of efficiency. For example, thunderstorms self-organize into squall lines as shown in the photo above.

Instead of individual areas of descending air around each individual thunderstorm, in a thermally-driven squall line you get long rolls of dry descending air along the flanks of the squall line. Because the carpet-roll-type circulation is streamlined, with the air smoothly rolling in a long tube, the squall line moves more energy from the surface to the upper troposphere than would be moved by the same number of individual thunderstorms.

To summarize the discussion so far:

There are four distinct successive emergent transitions from a quiescent stratified atmosphere to fully developed squall lines. Each is the result of self-organized criticality. Each one is a separate emergent phenomenon, coming into existence, persisting for some longer or shorter time, and then disappearing. In order, the transitions and the new emergent phenomena are:

- Still air to Rayleigh-Benard circulation

- Rayleigh-Benard circulation to cumulus field.

- Cumulus field to scattered thunderstorms

- Scattered thunderstorms to aggregated thunderstorms.

Each transition removes more energy from the surface to the atmosphere and thus eventually from the system.

Khairoutdinov and Emanuel discuss drying of descending air in only one of the states, the fourth one where thunderstorms aggregate. They are correct. However, this does not begin at the fourth stage. All the stages dry the descending air. And after each succeeding transition, the air becomes dryer and dryer.

I’ve demonstrated the close dependence of thunderstorms and “aggregated” thunderstorms on the surface temperature. I made up a movie showing this a while back using the CERES data, hang on … OK, here it is. I am using the extent of deep convection as measured by the cloud top heights as a measure of the strength of the thunderstorms and aggregates.

In the movie, you can see the thunderstorms and aggregated thunderstorms (color) following the warm water (gray lines) around the Pacific throughout the year.

And if we take a scatterplot of average cloud top altitude versus sea surface temperature, we find the following relationship:

Just as we saw in the movie above, when the sea surface temperature goes over about 26°C thunderstorms explode vertically, getting taller and taller. This is clear support for the idea that the transition between states is temperature-threshold based.

With all of that as prologue, let me move to the question of the descending dry air between the thunderstorms. I realized that we actually have some very good information about the amount of water in the air. This is data from the string of what are called the TAO/TRITON buoys and other moored buoys that stretch on both sides of the Equator around the world. Here are their locations.

Let me begin with another look at rainfall and temperature. Here’s a scatterplot of the sea surface temperature versus the rainfall in the equatorial Pacific area shown by the yellow box above (130°E – 90°W, 10°N/S). The blue dots below show results from the TAO buoys in the yellow box. The red dots show gridcell results from the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite rainfall data and Reynolds OI sea surface temperatures.

Man, I do love it when several totally independent datasets agree so well. In the graph above the blue dots are co-located measurements of average rainfall and sea surface temperature at individual TAO/Triton buoys. The red dots are 1° latitude by 1° longitude averages of Reynolds OI Sea Surface Temperatures, and Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite-based rainfall data. And in both datasets, we see once again that thunderstorms start forming in numbers only when sea surface temperatures get above about 26°C.

It’s also interesting that once the sea surface temperature gets into the upper-temperature range, there are no dry areas. Every place gets at least a certain minimum amount of rain. Not only that, but the minimum amount of annual rainfall increases smoothly and exponentially as the average sea surface temperature goes up.

Why is it so important that this threshold is temperature based? It’s important for what it is NOT. It is not forcing based. In other words, the great global thunderstorm-based air-conditioning and refrigeration system kicks in at about 26°C, no matter what the forcing is doing. No matter what the CO2 is doing. No matter what the volcanoes are doing. The regime shift from puffy white cumulus clouds to scattered thunderstorm towers kicks in when the temperature passes a temperature threshold, and not before, regardless of what CO2 does.

And this, in turn, means that these successive regime shifts, first to Rayleigh-Benard circulation, then to the cumulus field, then to scattered thunderstorms, and finally to aggregated thunderstorms, are functioning in a host of different ways to regulate and cap the surface temperature.

And finally, by a fairly circuitous but interesting route, we’ve arrived back at the question of the drying of the air in between the thunderstorms and thunderstorm aggregations.

There are eight TAO buoys that are directly on the Equator across the Pacific. It’s an interesting group because they all get identical sunshine. Despite getting identical solar energy, there is a temperature gradient from Central America across to Asia, with the Asian end at about 29°C and the South American end at about 24°C. So looking at these eight buoys gives us a look at how some phenomena vary by temperature.

Using the temperature and the relative humidity measurements from these buoys, I calculated the absolute humidity for each of them. This is the amount of water that is present per cubic metre of air. That number is important because the absorption of long-wave radiation by water vapor varies proportionally to the absolute humidity, not the relative humidity. Less absolute humidity means more surface heat loss by long-wave radiation to space.

These observations from the buoys are done every ten minutes. This allows me to calculate what an average day’s variations look like. To understand the daily variations, I aligned them at the morning minimums. Here are the records of those eight TAO buoys that are directly on the Equator.

In this graph, note that the warmer that the sea surface temperatures are, the smaller the 10 AM peak, and the more the afternoon absolute humidity drops from the 10 AM peak.

This is because as the thunderstorms form and increase the local area moisture is concentrated in the small area in and under the thunderstorms, with descending dry air between the thunderstorms making up the bulk of the lower troposphere. And in areas with warmer sea surface temperatures, shown in red above, clouds and thunderstorms form earlier, are denser, and at times form even larger aggregations of thunderstorms.

Now, what I’ve shown above are long term full-dataset averages. So it’s tempting to think “well, thunderstorms only happen where the average temperature is over 26°C”. But thunderstorms are not touched by averages. These temperature-regulating phenomena can appear, persist, and disappear at any time of day. All that matters are the instantaneous conditions. Whenever the tropical ocean gets warm enough, regardless of the longer-term averages for that location, you are likely to see thunderstorms form. All the averages mean is that the surface gets sufficiently hot to create thunderstorms on more or fewer days of the year.

My conclusions?

• K&E were right about the drying power of aggregated thunderstorms.

• It is also true that individual thunderstorms, as well as cumulus clouds and Rayleigh-Benard circulation, dry out the descending air.

• This lower level of water vapor cools the surface by increasing radiation loss to space and by increasing evaporation.

• This is only one of the host of ways that cumulus clouds and thunderstorms keep the tropics from overheating

• Rayleigh-Benard circulation, cumulus fields, scattered thunderstorms, and aggregated thunderstorms are all emergent phenomena. They emerge wherever there is sufficient surface heat, meaning when the temperature exceeds some local threshold. Each succeeding state, in turn, starts removing more heat from the surface. This is an extremely efficient temperature regulating system because they emerge only as and where there are local concentrations of surface heat.

Finally, I want to emphasize one of K&E’s interesting claims:

Such dramatic drying would reduce the greenhouse effect associated with the water vapor, and thus, would lead to cooling of the SST, which in turn may disaggregate convection. This would re-moisten the atmosphere, increasing the water-vapor greenhouse effect, and, consequently, warming the system. So, as in self-organized criticality (SOC), the tropical state would be attracted to the transition critical state between the aggregated and disaggregated states.

In other words, all of these phenomena act to stabilize the temperature.

Here, sunshine. Life is good. My very best wishes to all.

w.

My Usual Request: When you comment please quote the exact words that you are referring to, so we can all understand your subject.

ENDNOTE—COOLING MECHANISMS

K&E are looking just at increased radiation through dryer air. This is only one of the many ways that thunderstorms cool the surface. Here’s a more complete list.

• Refrigeration-cycle cooling. A home refrigerator evaporates a working fluid in one location and condenses it in another location. This removes heat in the form of latent heat of evaporation/condensation. The thunderstorm uses the exact same cycle. For the thunderstorm the working fluid is water. Water evaporates at the surface and is carried aloft via the thunderstorm circulation. This, of course, removes surface heat in the form of latent heat. Then, just as in a domestic refrigeration cycle, the working fluid condenses at altitude in the thunderstorm base and falls back as a cold liquid to the surface.

• Self-generated evaporative cooling. Once the thunderstorm starts, it creates its own wind around the base. This self-generated wind increases evaporation in several ways, particularly over the ocean.

- a) Evaporation rises linearly with wind speed. At a typical squall wind speed of 10 mps (20 knots), evaporation is about ten times higher than at “calm” conditions (conventionally taken as 1 mps).

- b) The wind increases evaporation by creating spray and foam, and by blowing water off of trees and leaves. These greatly increase the evaporative surface area, because the total surface area of the millions of droplets is evaporating as well as the actual surface itself.

- c) To a lesser extent, surface area is also increased by wind-created waves (a wavy surface has a larger evaporative area than a flat surface).

- d) Wind created waves in turn greatly increase turbulence in the atmospheric boundary layer. This increases evaporation by mixing dry air down to the surface and moist air upwards.

• Wind-driven albedo increase. The white spray, foam, spindrift, changing angles of incidence, and white breaking wave tops greatly increase the albedo of the sea surface. This reduces the energy absorbed by the ocean.

• Cold rain and cold wind. As the moist air rises inside the thunderstorm’s heat pipe, water condenses and falls. Since the water is originating from condensing or freezing temperatures aloft, it cools the lower atmosphere it falls through, and it cools the surface when it hits. In addition, the falling rain entrains a cold wind. This cold wind blows radially outwards from the center of the falling rain, cooling the surrounding area.

• Increased reflective area. White fluffy cumulus clouds are not tall, so basically they only reflect from the tops. On the other hand, the vertical pipe of the thunderstorm reflects sunlight along its entire length. This means that thunderstorms shade an area of the ocean out of proportion to their footprint, particularly in the late afternoon.

• Modification of upper tropospheric ice crystal cloud amounts (Lindzen 2001, Spencer 2007). These clouds form from the tiny ice particles that come out of the smokestack of the thunderstorm heat engines. It appears that the regulation of these clouds has a large effect, as they are thought to warm (through IR absorption) more than they cool (through reflection).

• Enhanced night-time radiation. Unlike long-lived stratus clouds, cumulus and cumulonimbus often die out and vanish as the night cools, leading to the typically clear skies at dawn. This allows greatly increased nighttime surface radiative cooling to space.

• Delivery of dry air to the surface. The air being sucked from the surface and lifted to altitude is counterbalanced by a descending flow of replacement air emitted from the top of the thunderstorm. This descending air has had the majority of the water vapor stripped out of it inside the thunderstorm, so it is relatively dry. The dryer the air, the more moisture it can pick up for the next trip to the sky. This increases the evaporative cooling of the surface as well as allowing more radiative loss to space.

Meanwhile. here on the north shore of Lake Ontario, today, I drove through a dark snow squall streaming off Lake Huron on a ‘partly cloudy’ day.

Thank You Willis,

This is an excellent, clear, concise and informative explanation of the processes and related effects associated with cumulus cloud formation.

It occurred to me, while reading your article; that the processes which you describe are a microcosm of those that occur in Hadley cell circulation.

On a larger scale, warm moist air rises in the tropics precipitates rain the returns to the earth’s surface as dry cool air at the “Horse Latitudes”, resulting in humid tropical areas (Brazil and central Africa) and arid areas along the margin of the downgoing cool and dry air in northern Mexico and North and South Africa.

Your graphs of sea Surface Temperature vs Rain per year and cloud top Height and especially the 26 deg.C ocean temperature were especially interesting.

It occurred to me that this important cumulus cloud formation process and critical temperature could significantly be affected by changes in the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and the Atlantic multi-Decadal oscillation, whereby changes in the surface water temperature of global water pools oscillating above and below 26 deg C (your critical observed temperature) would have a profound effect on the global radiator. Positive and negative PDO and AMO systems (and their coincidence and offset in time) which have been positively correlated to regional warming/cooling as well as to rainfall/drought.

I am also curious about how the changes in the altitude of the dewpoint temperature could affect the overall heat transfer from the Earth’s surface to the upper atmosphere, and if these controls change with major decadal oscillations of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans?

However speculative some of these thoughts may be, I am grateful for your excellent review of these very important processes.

Muchas Gracias,

John R.

“…the surface temperature is running some thirty degrees C or more warmer than would be expected given the strength of the sun.”

It seems to me that all the stabilizing mechanisms described tend to cool the surface. How does that increase the surface temperature by 30C, and why precisely 30C?

otropogo January 8, 2020 at 9:53 pm

Good questions. First, it’s not “precisely 30°C”, we don’t really know how warm the planet would be without the greenhouse effect. See Dr. Robert Brown’s excellent post here.

Next, the earth is warmer than we would expect from its distance from the sun. This is from the poorly named “greenhouse effect”, which has nothing to do with greenhouses. See my posts on how it works here and here.

However, the temperature of the earth is capped by a variety of emergent phenomena, some of which I discussed above, that keep it from overheating. See here for details.

Once you’ve read those four, if you still have questions, come back here and post them. WUWT is a great place to learn things.

Best to you,

w.

>Next, the earth is warmer than we would expect from its distance from the planet

I think you mean “its distance from the _sun_”

Thanks, Andrew, fixed.

w.

Willis,

Your last graph showing the diurnal variation of the absolute humidity anomaly looks familiar. In the tropics, away from areas affected by cyclones, typhoons, hurricanes, and tropical storms, there is an almost universal diurnal variation in mean sea-level (atmospheric) pressure (MSLP). The MSLP reaches a minimum at 4:00 A.M. and 4:00 P.M., and a maximum at 10:00 A.M. and 10:00 P.M. This is exactly the same type variation seen in the absolute humidity anomaly. I wonder if these two phenomena are connected somehow?

It would be interesting to make a plot of the absolute humidity anomaly against MSLP, at a number of representative sights along the equator. According to your graph, there should be a secondary effect caused by the local SST.

Willis,

Your cloud top altitude graphic of this article, and your SST graphic from….https://wattsupwiththat.com/2019/12/26/a-decided-lack-of-equilibrium/

seem to show strong temperature limiting phenomenon at warm SST that would help explain why climate models are not in line with actual readings. In fact force one to the conclusion that the models are lucky to be in the ballpark….

Willis, on the subject of turbulence, which is what the atmosphere is all about, we all have a very serious problem.

During his entire career, Richard Feynman had identified turbulence as “the most important unresolved problem of classical physics.” Feynman reported to the British Association for the Advancement of Science: “I am an old man now, and when I die and go to heaven, there are two matters on which I hope for enlightenment. One is quantum electrodynamics, and the other is the turbulent motion of fluids. And about the former I am rather optimistic.” (Parviz Moin and John Kim, Tackling Turbulence with Supercomputers, http://www.stanford.edu/group/ctr/articles/tackle.html)

I think what you mean by “emergent” self-organization is exactly the problem Feynman was not optimistic about. So all climateers are forced into an empirical mode, or a modelling mode with each group, money or politics aside, cornered into huge arguments.

This all began in the 1950’s with the failure to deal with , believe it or not, plasma turbulence, self-organinsing fusion pinches. That is what fusion is all about, and the failure to pursue this even when existing maths cannot handle it, has culminated in an economy with no fusion energy, and an unbelievable decadent quarrel about “climate” with CO2 soothsayers and doom merchants, a real dark age.

In other words, fusion plama pushes self-organied emergent phenomena this to the limit. Climate is by comparison, mild.

I think climate and fusion puts people like Mann in the unenviable role of the emperor with no clothes.

Meanwhile galaxies, stellar systems, DNA, and climate self-organize for everyone to see with wonder.

Dr. Parviz Moin has many publications on this —- the link moved a bit.

https://profiles.stanford.edu/parviz-moin?tab=publications

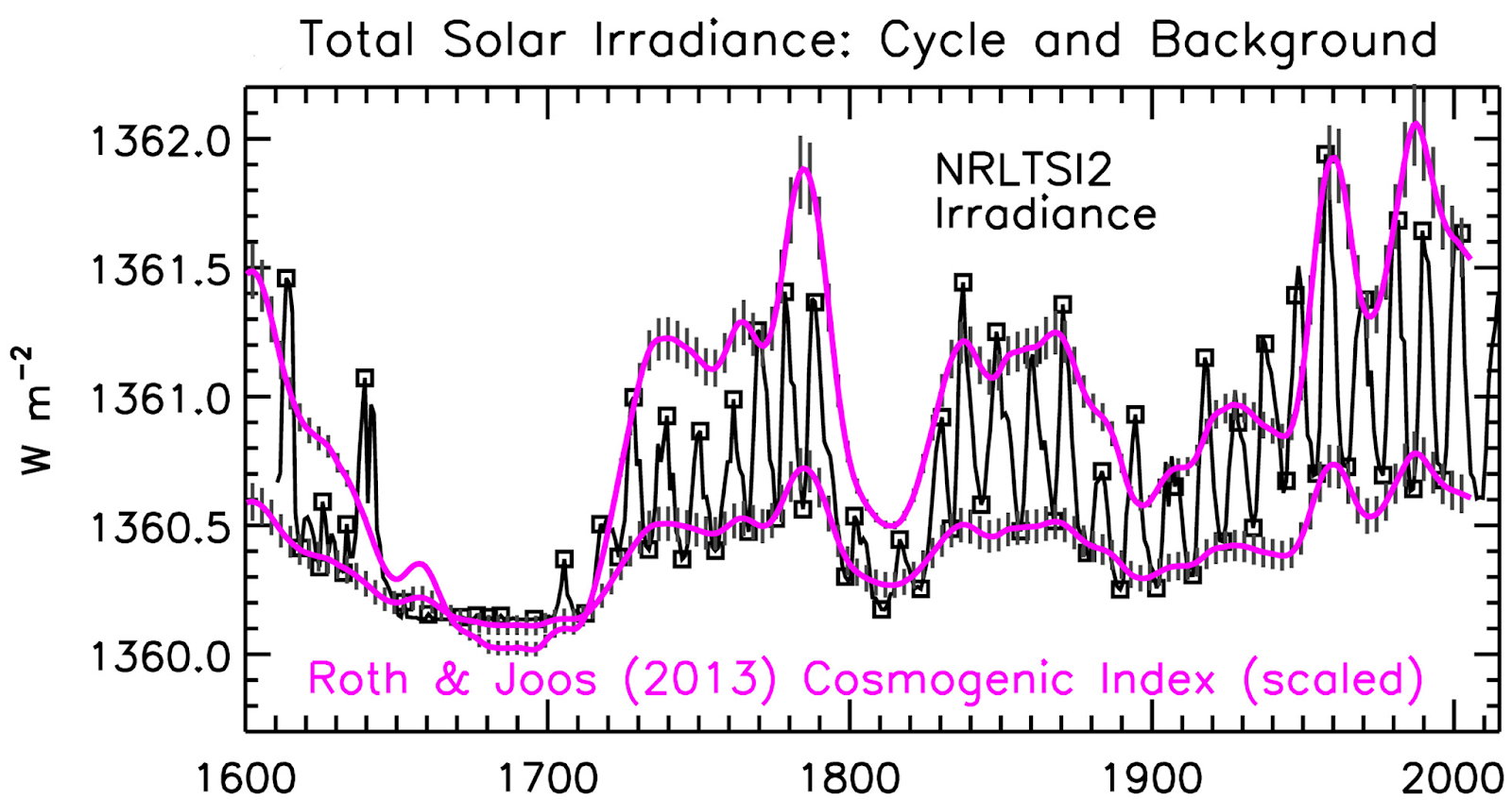

Bon Bon You can regard the graphs of global temperatures as emergent properties of the combined astronomical and solar activity cycles. My WUWT comment of 12/27 deals exactly with your points.

“Simple common sense suggests that a Millennial Solar activity peak was reached in 1991 +/- and a corresponding global temperature peak and turning point from warming to cooling was reached at 2004+/-.It’s not “rocket science” or a “wicked problem” in the long term. Reasonably plausible multidecadal to millennial length forecasts can be made with useful probable accuracy. Shorter term decadal and weather forecasting is much more difficult.

Here is the Abstract from my 2017 paper linked below

“This paper argues that the methods used by the establishment climate science community are not fit for purpose and that a new forecasting paradigm should be adopted. Earth’s climate is the result of resonances and beats between various quasi-cyclic processes of varying wavelengths. It is not possible to forecast the future unless we have a good understanding of where the earth is in time in relation to the current phases of those different interacting natural quasi periodicities. Evidence is presented specifying the timing and amplitude of the natural 60+/- year and, more importantly, 1,000 year periodicities (observed emergent behaviors) that are so obvious in the temperature record. Data related to the solar climate driver is discussed and the solar cycle 22 low in the neutron count (high solar activity) in 1991 is identified as a solar activity millennial peak and correlated with the millennial peak -inversion point – in the RSS temperature trend in about 2003. The cyclic trends are projected forward and predict a probable general temperature decline in the coming decades and centuries. Estimates of the timing and amplitude of the coming cooling are made. If the real climate outcomes follow a trend which approaches the near term forecasts of this working hypothesis, the divergence between the IPCC forecasts and those projected by this paper will be so large by 2021 as to make the current, supposedly actionable, level of confidence in the IPCC forecasts untenable.”

These general trends were disturbed by the Super El Nino of 2016/17. The effect of this short term event have been dissipating so that “If the real climate outcomes follow a trend which approaches the near term forecasts of this working hypothesis, the divergence between the IPCC forecasts and those projected by this paper will be so large by 2021 as to make the current, supposedly actionable, level of confidence in the IPCC forecasts untenable.”

See my 2017 paper “The coming cooling: Usefully accurate climate forecasting for policy makers.”

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0958305X16686488

and an earlier accessible blog version at

http://climatesense-norpag.blogspot.com/2017/02/the-coming-cooling-usefully-accurate_17.html

And /or My Blog-posts http://climatesense-norpag.blogspot.com/2018/10/the-millennial-turning-point-solar.html ( See Fig1)

and https://climatesense-norpag.blogspot.com/2019/01/the-co2-derangement-syndrome-millennial.html

also see the discussion with Professor William Happer at http://climatesense-norpag.blogspot.com/2018/02/exchange-with-professor-happer-princeton.html

For the current situation check the RSS data at : http://images.remss.com/data/msu/graphics/TLT_v40/time_series/RSS_TS_channel_TLT_Global_Land_And_Sea_v04_0.txt

I pick the Millennial turning point peak here at 2005 – 4 at 0.58

I suggest that if the 2021 temperature is lower than that (16 years without warming ) the crisis forecasts would obviously be seriously questionable and provide no secure basis for restructuring the world economy at a cost of trillions of dollars.

The El Nino RSS peak was at 2016 – 2 at 1.2

Latest month was 2019-11 at 0.71

However the whole UNFCCC circus was designed to produce action even without empirical

justification. See

https://climatesense-norpag.blogspot.com/2019/01/the-co2-derangement-syndrome-millennial.html

” United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, later signed by 196 governments.

The objective of the Convention is to keep CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that they guessed would prevent dangerous man made interference with the climate system.

This treaty is a comprehensive, politically driven, political action plan called Agenda 21 designed to produce a centrally managed global society which would control every aspect of the life of every one on earth.

It says :

“The Parties should take precautionary measures to anticipate, prevent or minimize the

causes of climate change and mitigate its adverse effects. Where there are threats of serious or

irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing

such measures”

Apocalyptic forecasts are used as the main drivers of demands for action and for enormous investments such as those in the new IPCC SR1.5 report .”

The establishment’s dangerous global warming meme, the associated IPCC series of reports ,the entire UNFCCC circus, the recent hysterical IPCC SR1.5 proposals and Nordhaus’ recent Nobel prize are founded on two basic errors in scientific judgement. First – the sample size is too small. Most IPCC model studies retrofit from the present back for only 100 – 150 years when the currently most important climate controlling, largest amplitude, solar activity cycle is millennial. This means that all climate model temperature outcomes are too hot and likely fall outside of the real future world. (See Kahneman -. Thinking Fast and Slow p 118) Second – the models make the fundamental scientific error of forecasting straight ahead beyond the Millennial Turning Point (MTP) and peak in solar activity which was reached in 1991.These errors are compounded by confirmation bias and academic consensus group think.

The editors of Science and Nature magazines have acted as Guardians of the establishment position and have sought to promote radical solutions to a non existent warming problem. Most of the MSM, particularly the BBC, and the western eco-left chattering classes now promote anti-development anti-capitalist crisis ideologies based on badly flawed science.

Great post and astonishing video of tropical cloud formation — the development of the squall line is amazing.

Willis many thanks for a superb seminal post. Your Daily Solar Energy chart clearly shows the unimportance of CO2 in the process . It would be even more obvious if you had the time and/or inclination to estimate the volume of air, water and CO2 passing through a typical (Model ?)tropical thunderstorm daily and then show the relative energy flows of H2O and CO2. The specific heat capacity of water is 4,200 Joules per kilogram per degree Celsius (J/kg°C).The nominal values used for air at 300 K are Cp= 1.00 kJ/kg.K, and for CO2 Cp 37.35 kJ/kg

Found it.

Water Albedo, Wind-Roughened Surface

https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/pdf/10.1175/1520-0469%281954%29011%3C0283%3AAOWRW%3E2.0.CO%3B2

JF

Thanks, Julian, most fascinating. I generally use the table from my bible, “The Climate Near The Ground” by Geiger

Globally, per CERES the average albedo of the ocean is 9.5%

w.

Willis, I posted a question the 7th, so assume it won’t be answered directly.

I’ll try again.

How do you envision the tropics to overheat?

Tropics are mostly ocean, and a good day of sunshine in the tropics delivers some 25 MJ/m^2 to these oceans. Since the sun directly warms only the upper 5-10 m directly, this roughly enough energy to warm this column 1K. During the night this “stored” energy is lost again to the atmosphere/space.

I’ll expand a little:

our moon is warmed by ~89% of solar. Due to the low heat capacity and low conductivity of the regolith on top of the slower rotation rate the noon temperatures on the equator go to radiative balance temps, ~400K.

In our tropics the atmosphere reduces the amount of solar that hits the surface to ~160 W/m^2 (< 50%).

This amounts to ~25 MJ/m^2 on a sunny day.

https://www.pveducation.org/pvcdrom/properties-of-sunlight/isoflux-contour-plots

Sunlight penetrates the oceans down to max 100m, actual warming is in the upper 5-10m.

Earth has a faster rotation rate, oceans have high heat capacity and high conductivity.

So the 25 MJ/m^2 can warm the upper 5-10m ~1K during the day. During the night this energy is lost again.

https://www.ghrsst.org/ghrsst-data-services/products/

(scroll down for the image)

So again my question: how do you see the tropical ocean overheating?

Ben Wouters January 12, 2020 at 12:26 pm

Ben, sorry I missed it.

If there were no clouds to reflect sunlight, the tropics (and the whole world as well) would receive ~ 45 W/m2 more energy on a constant 24/7/365 basis.

And IF there were no emergent phenomena to stop overheating, per the IPCC this increase in forcing would increase the temperature by 45 / 3.7 * 3°C = 36°C … It’s the forcing equivalent of 12+ doublings of CO2, which would take CO2 from 400 ppmv to 1,833,309 ppmv.

And that’s not even counting the myriad ways that thunderstorms cool the surface.

Best to you,

w.

Willis Eschenbach January 12, 2020 at 12:45 pm

Let’s use the same number as for Australian desert in summer (no clouds, little WV): ~30 MJ/m^2.

https://www.pveducation.org/pvcdrom/properties-of-sunlight/isoflux-contour-plots

Enough energy to warm the upper ~7m of ocean 1K during the day, iso the ~6m with 25 MJ/m^2.

No clouds means more energy loss, so the extra energy will be lost during the night again most probably.

I see no reason for overheating at all.

Underlying point is obviously that we must consider the heat capacity and penetration of solar into the surface being heated.

Thinking in radiative balance temperatures works on the moon, but not for our ocean covered earth.

Ben, I fear that makes no sense. 30 MJ/m^2 over how long a time period?

In any case, your point seems to be that if you pick an area where there are no clouds, removing clouds makes little difference … true, but that’s not true of most of the planet.

Overall, the net cooling effect (additional solar minus additional longwave) of the clouds is about 17 W/m2. However, that does not include the huge cooling effect of thunderstorms via a host of mechanisms I listed above.

Per the IPCC, just that 17 W/m2 alone of extra forcing would increase global temperatures by 17/3.7*3 = 14°C … like I said …

Finally, I don’t understand your claim at all about the “penetration of the solar”. If you turn up the sun by 17 W/m2, what difference does depth of penetration make? Also, that 17 W/m2 is a 24/7/365 average, so your claims about “lost during the night” are not relevant. That’s already been taken into account.

w.

Willis Eschenbach January 12, 2020 at 3:07 pm

From below the plots: Average quarterly global isoflux contour plots for each quarter in the year. The units are in MJ/m2 and give the solar insolation falling on a horizontal surface per day.

No , my point is that by picking an area like the Australian dessert, it is representative for the maximum energy the sun can deliver in the (sub)tropics in full summer over the course of one day. 30 MJ/m^2/day is the maximum we’ll find on earth.

Consider a beach, with nearby shallow salt pans filled with seawater (eg 0,5 meter deep) and of course the oceans.

During a day they will receive the exact same amount of solar energy.

The sand will heat up the most, but only some 10-20 centimeters deep.

Next the salt pans, less warm, but at least halve a meter water has been heated.

Finally the ocean, warmed down to 5-10 m, but only 1, maybe two degrees warmer.

So penetration depth together with heat capacity decides how much the temperature will rise during a day.

Same for the seasonal variations.

From this site http://research.cfos.uaf.edu/gak1/

http://research.cfos.uaf.edu/gak1/gak1_MonthlyT.png

During a whole season of warming the upper surface temp increases some 10 degrees,

deeper water less, below ~250 m no seasonal change at all.

For available energy go to Anchorage on this map:

https://www.pveducation.org/pvcdrom/properties-of-sunlight/average-solar-radiation

Units are kWh/m^2/day. Multiply with 3,6 to get MJ/m^2/day.

The incredible stability of Earth’s surface temperatures is due to the oceans imo.

Thanks, Ben. Your figures for the Aussie outback seem accurate. You say:

However, the problem with that claim is that the Aussie outback is not cloudless. In fact, it has cloud cover some 10% of the time, even in midsummer. So if there were no clouds, even the outback would be hotter …

Next, you say:

We’re not talking about a day or a month here. If there were no clouds, after thousands of years the ocean would equilibrate and things would be … well … damn hot. Hotter than the Australian outback hot.

Finally, the stability of the earth’s temperature is clearly not due to the oceans. As you point out, every year the surface temperature of the ocean swings by ten degrees or so … so clearly the ocean can easily and quickly change temperature. And the land cannot be ignored, it’s 30% of the surface with an average annual swing of 30°C.

But despite those annual swings, it comes back to where it started. There’s no reason a priori that it should return to the previous temperature, since the clouds and aerosols and evaporation and sensible heat transfer are all varying like crazy, both in time and space. But every year, all of those individually varying factors average out.

And with all of that … the global average temperature varied less than one degree over the last century.

Here’s another data point in that regard. The northern hemisphere is about 60% ocean. The southern hemisphere is about 80% ocean. Despite that, the albedo of each hemisphere is nearly identical. See here for details. I say this is another indication that there are emergent thermoregulatory processes controlling the temperature.

My best to you, interesting questions all.

w.

Willis Eschenbach January 13, 2020 at 10:42 am

Fine. Fact remains that it is one of the places with the highest amount of solar/day, together with the other deserts in the high pressure belts N and S of the Equator.

If clouds develop, they certainly won’t be of the Cumulonimbus type.

30 MJ/m^2/day is the maximum amount of solar these charts show.

Do you agree that the beach has the highest temperature swing during a day of the 3 examples, and the oceans the lowest? (beach maybe 30C swing, oceans 1 or 2 degrees.)

If not the difference in penetration depth and heat capacity, what is your explanation.

Realize that the daily tropical thunderstorms mainly develop over (is)land, not so much over sea.

No clouds means more solar during the day, but also more radiative loss to space. It’s far from sure which of those effects overrules the other.

So far the (deep) oceans have on average been cooling down for the last ~85 my.

In the example of GAK1 i showed the temperature swing is only for the upper 50m or so, and caused by the variation in solar energy during the day from practically zero in winter to ~18 MJ/m^2/day in mid summer (Anchorage).

Cooling during the winter is limited by the temperature of the deeper oceans.

The 60N profile shows the temperature below the 250m of the GAK1 plot.

The temperature of oceans below the solar heated surface layer is what creates the base for the surface temperatures. It is about the same for the whole world, and hardly changes on human time scales => stability.

Great article, Willis.

When I discussed your article with some folks, they criticized that the first claim doesn’t come with indication of the source:

“…e.g. ± 0.3°C over the entire 20th Century. This represents a temperature variation …”

I know you have stated the 0.3° in several of your post, but I wasn’t able to find to which data this refers. And common temperature series such as GISTEMP show a variation of >1° for the 20th Century.

Peter, the trend in the 20th Century HadCRUT global surface temperature data is 0.62°C per century … which I’ve described as “±0.3°C”, or perhaps more accurately, it’s the HadCRUT global average temperature over the period of 13.9° ± 0.3°C.

GISTEMP is from the lying liars over at GISS, me, I never touch that one.

I’ll edit the head post to reflect your concerns.

w.

Willis, I have quit a few points about your concept of atmospheric convection as used in the main text.

Are you interested to discuss this?

Ben Wouters January 14, 2020 at 6:37 am

Ben, I fear discussing things with you is immensely frustrating. For example, I said:

I then said:

Totally ignoring my earlier statement, you reply

No, it’s not “far from sure” at all. I just gave you the best scientific estimate, and it shows (as you’d expect) that clouds cool the surface including the radiative loss to space. Not only that, it shows by how much clouds cool the surface—about 17 W/m2.

So I fear I’m gonna pass. I have little time and less interest in saying things that simply get ignored.

Please don’t take this as an indictment of your ideas. You may well be right. I just don’t have time to go on a merry-go-round ride that has lots of lights, music, and action, but which at the end of the day goes nowhere …

Best regards,

w.

Willis Eschenbach January 14, 2020 at 8:29 am

Problem is that your concepts are based on two incompatible ideas:

– the atmosphere “further heats” the surface (Lacis ea 2010) above the 255K the sun provided.

– the surface will overheat when the atmosphere does not cool it with clouds, developing CB’s etc.

By introducing a simple idea of using the available MJ/m^2 during a day iso the average W/m^2 a lot of observations make sense. Anyone who has burned his foot soles on a hot beach also has noticed that the water is much colder.

Once you realize that the sun is not warming the entire oceans from 0K to the observed values, but only increasing the temperature of a shallow surface layer a bit, the very high temperatures on earth make perfect sense.

Next step is to accept that the deep oceans are so hot (~275K) for the same reason the continental crust is hot in spite of the low flux (~65 mW/m^2) : Earth’s incredibly hot interior.

And yes, the atmosphere does reduce the energy loss to space, and yes backradiation from the atmosphere does play a role in this process.

Great Post, thanks Willis!

TAO: https://www.google.com/search?q=TAO+buoy&client=ms-android-huawei&sourceid=chrome-mobile&ie=UTF-8&ctxr&ctxsl_trans=1&tlitetl=de&tlitetxt=TAO%20buoy

Great Post, thanks Willis!

Had to look up TAO: https://www.google.com/search?q=TAO+buoy&client=ms-android-huawei&sourceid=chrome-mobile&ie=UTF-8&ctxr&ctxsl_trans=1&tlitetl=de&tlitetxt=TAO%20buoy

With that compilation of atmospheric / sea surface fluid mechanics, local heat distribution, localised albedo effects ad lib. / ad inf.

– there’s shown: still a long way even for “super-computers” to catch up with.