Reposted from Dr. Susan Crockford’s Polar Bear Science

Posted on July 12, 2019 |

Summer sea ice loss is finally ramping up: first year is disappearing, as it has done every year since ice came to the Arctic millions of years ago. But critical misconceptions, fallacies, and disinformation abound regarding Arctic sea ice and polar bear survival. Ahead of Arctic Sea Ice Day (15 July), here are 10 fallacies that teachers and parents especially need to know about.

The cartoon above was done by Josh: you can drop off the price of a beer (or more) for his efforts here.

As always, please contact me if you would like to examine any of the references included in this post. These references are what make my efforts different from the activist organization Polar Bears International. PBI virtually never provide references within the content it provides, including material it presents as ‘educational’. Links to previous posts of mine that provide expanded explanations, images, and additional references are provided.

Sea ice background: extent over the last year

Summer sea ice minimum 2018 (from NSIDC):

Winter sea ice maximum 2019:

Sea ice at 7 July 2019: early summer extent

Despite the fact that 2019 had the 2nd lowest extent for the month of June since 1979, by early July, there was still ice adjacent to all major polar bear denning areas across the Arctic. In many regions, pregnant females that give birth on land in December come ashore in summer and stay until their newborn cubs are old enough to return with them to the ice the following spring. See Andersen et al. 2012; Ferguson et al. 2000; Garner et al. 1994; Jonkel et al. 1978; Harington 1968; Kochnev 2018; Kolenosky and Prevett 1983; Larsen 1985; Olson et al. 2017; Richardson et al. 2005; Stirling and Andriashek 1992.

Ten fallacies and disinformation about sea ice

1. ‘Sea ice is to the Arctic as soil is to a forest‘. False: this all-or-nothing analogy is an specious comparison. In fact, Arctic sea ice is like a big wetland pond that dries up a bit every summer, where the amount of habitat available to sustain aquatic plants, amphibians and insects is reduced but does not disappear completely. Wetland species are adapted to this habitat: they are able to survive the reduced water availability in the dry season because it happens every year. Similarly, sea ice will always reform in the winter and stay until spring. During the two million or so years that ice has formed in the Arctic, there has always been ice in the winter and spring (even in warmer Interglacials than this one). Moreover, I am not aware of a single modern climate model that predicts winter ice will fail to develop over the next 80 years or so. See Amstrup et al. 2007; Durner et al. 2009; Gibbard et al. 2007; Polak et al. 2010; Stroeve et al. 2007.

2. Polar bears need summer sea ice to survive. False: polar bears that have fed adequately on young seals in the early spring can live off their fat for five months or more until the fall, whether they spend the summer on land or the Arctic pack ice. Polar bears seldom catch seals in the summer because only predator-savvy adult seals are available and holes in the pack ice allow the seals many opportunities to escape (see the BBC video below). Polar bears and Arctic seals truly require sea ice from late fall through early spring only. See Crockford 2017, 2019; Hammill and Smith 1991:132; Obbard et al. 2016; Pilfold et al. 2016; Stirling 1974; Stirling and Øritsland 1995; Whiteman et al. 2015.

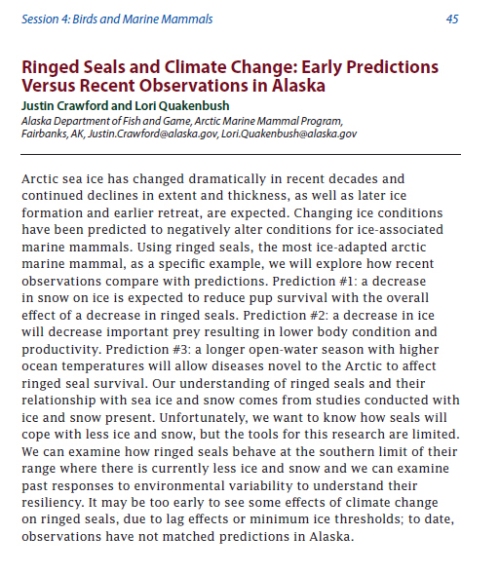

3. Ice algae is the basis for all Arctic life. Only partially true: plankton also thrives in open water during the Arctic summer, which ultimately provides food for the fish species that ringed and bearded seals depend upon to fatten up before the long Arctic winter. Recent research has shown that less ice in summer has improved ringed and bearded seal health and survival over conditions that existed in the 1980s (when there was a shorter ice-free season and fewer fish to eat): as a consequence, abundant seal populations have been a boon for the polar bears that depend on them for food in early spring. For example, despite living with the most profound decline of summer sea ice in the Arctic polar bears in the Barents Sea around Svalbard are thriving, as are Chukchi Sea polar bears – both contrary to predictions made in 2007 that resulted in polar bears being declared ‘threatened’ with extinction under the Endangered Species Act. See Aars 2018; Aars et al. 2017; Amstrup et al. 2007; Arrigo and van Dijken 2015; Crawford and Quadenbush 2013; Crawford et al. 2015; Crockford 2017, 2019; Frey et al. 2018; Kovacs et al. 2016; Lowry 2016; Regehr et al. 2018; Rode and Regehr 2010; Rode et al. 2013, 2014, 2015, 2018.

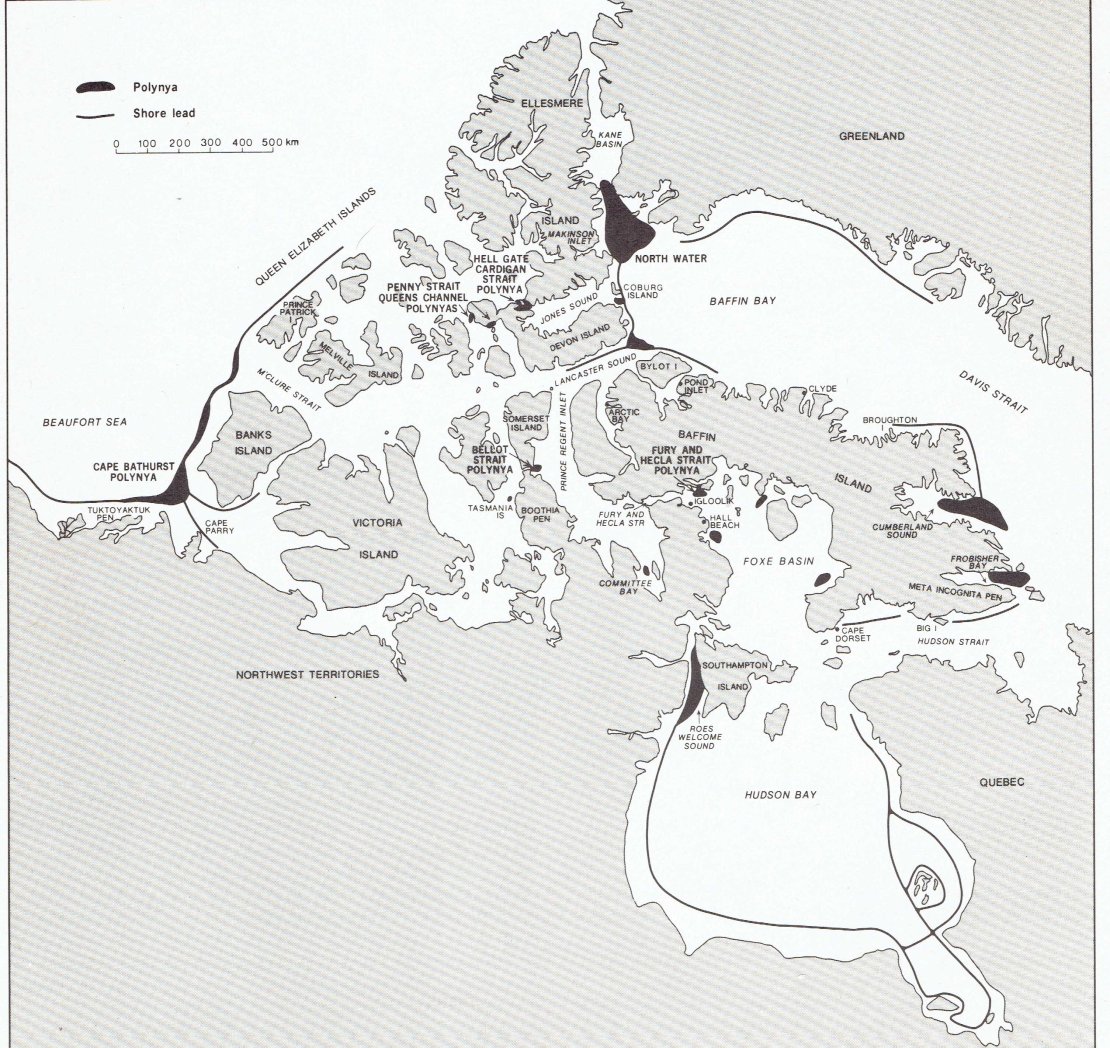

4. Open water in early spring as well as summer ice melt since 1979 are unnatural and detrimental to polar bear survival. False: melting ice is a normal part of the seasonal changes in the Arctic. In the winter and spring, a number of areas of open water appear because wind and currents rearrange the pack ice – this is not melt, but rather normal polynya formation and expansion. Polynyas and widening shore leads provide a beneficial mix of ice resting platform and nutrient-laden open water that attracts Arctic seals and provides excellent hunting opportunities for polar bears. The map below shows Canadian polynyas and shore leads known in the 1970s : similar patches of open water routinely develop in spring off eastern Greenland and along the Russian coast of the Arctic Ocean. See Dunbar 1981; Grenfell and Maykut 1977; Hare and Montgomery 1949; Smith and Rigby 1981; Stirling and Cleator 1981; Stirling et al. 1981, 1993.

Recurring polynyas and shore leads in Canada known in the 1970s. From Smith and Rigby 1981

5. Climate models do a good job of predicting future polar bear habitat. False: My recent book, The Polar Bear Catastrophe That Never Happened, explains that the almost 50% decline in summer sea ice that was not expected until 2050 actually arrived in 2007, where it has been ever since (yet polar bears are thriving). That is an extraordinarily bad track record of sea ice prediction. Also, contrary to predictions made by climate modelers, first year ice has already replaced much of the multi-year ice in the southern and eastern portion of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, to the benefit of polar bears. See also ACIA 2005; Crockford 2017, 2019; Durner et al. 2009; Hamilton et al. 2014; Heide-Jorgensen et al. 2012; Perovich et al. 2018; Stern and Laidre 2016; Stroeve et al. 2007; SWG 2016; Wang and Overland 2012.

Simplified predictions vs. observations up to 2007 provided by Stroeve et al. 2007 (courtesy Wikimedia). Sea ice hit an even lower extent in 2012 and all years since then have been below predicted levels.

6. Sea ice is getting thinner and that’s a problem for polar bears. False: First year ice (less than about 2 metres thick) is the best habit for polar bears because it is also the best habitat for Arctic seals. Very thick multi-year ice that has been replaced by first year ice that melts completely every summer creates more good habitat for seals and bears in the spring, when they need it the most. This has happened especially in the southern and eastern portions of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago (see ice chart below from Sept 2016). Because of such changes in ice thickness, the population of polar bears in Kane Basin (off NW Greenland) has more than doubled since the late 1990s. See Atwood et al. 2016; Durner et al. 2009; Lang et al. 2017; Stirling et al. 1993; SWG 2016.

7. Polar bears in Western and Southern Hudson Bay are most at risk of extinction due to global warming. False: Ice decline in Hudson Bay has been among the lowest across the Arctic. Sea ice decline in Hudson Bay (see graphs below) has been less than one day per year since 1979 compared to more than 4 days per year in the Barents Sea. Hudson Bay ice decline also uniquely happened as a sudden step-change in 1998: there has not been a slow and steady decline. Since 1998, the ice-free season in Western Hudson Bay has been about 3 weeks longer overall than it was in the 1980s but has not become any longer over the last 20 years despite declines in total Arctic sea ice extent or increased carbon dioxide emissions. See Castro de la Guardia et al. 2017; Regehr et al. 2016.

Loss of summer sea ice per year, 1979-2014. From Regehr et al. 2016.

8. Breakup of sea ice in Western Hudson Bay now occurs three weeks earlier than it did in the 1980s. False: Breakup now occurs about 2 weeks earlier in summer than it did in the 1980s. The total length of the ice-free season is now about 3 weeks longer (with lots of year-to-year variation). See Castro de la Guardia et al. 2017; Cherry et al. 2013; Lunn et al. 2016; and vidoe below, showing the first bear spotted off the ice at Cape Churchill, Western Hudson Bay, on 5 July 2019 – fat and healthy after eating well during the spring:

9. Winter sea ice has been declining since 1979, putting polar bear survival at risk. Only partially true: while sea ice in winter (i.e. March) has been declining gradually since 1979 (see graph below from NOAA), there is no evidence to suggest this has negatively impacted polar bear health or survival, as the decline has been quite minimal. The sea ice chart at the beginning of this post shows that in 2019 there was plenty of ice remaining in March to meet the needs of polar bears and their primary prey (ringed and bearded seals), despite it being the 7th lowest since 1979.

10. Experts say that with 19 different polar bear subpopulations across the Arctic, there are “19 sea ice scenarios playing out“ (see also here), implying this is what they predicted all along. False: In order to predict the future survival of polar bears, biologists at the US Geological Survey in 2007 grouped polar bear subpopulations with similar sea ice types (which they called ‘polar bear ecoregions,’ see map below). Their predictions of polar bear survival were based on assumptions of how the ice in these four sea ice regions would change over time (with areas in purple and green being similarly extremely vulnerable to effects of climate change). However, it turns out that there is much more variation than they expected: contrary to predictions, the Barents Sea has had a far greater decline in summer ice extent than any other region, and both Western and Southern Hudson Bay have had relatively little (see #7). See Amstrup et al. 2007; Crockford 2017, 2019; Durner et al. 2009; Atwood et al. 2016; Regehr et al. 2016.

References

Aars, J. 2018. Population changes in polar bears: protected, but quickly losing habitat. Fram Forum Newsletter 2018. Fram Centre, Tromso. Download pdf here (32 mb).

Aars, J., Marques,T.A, Lone, K., Anderson, M., Wiig, Ø., Fløystad, I.M.B., Hagen, S.B. and Buckland, S.T. 2017. The number and distribution of polar bears in the western Barents Sea. Polar Research 36:1. 1374125. doi:10.1080/17518369.2017.1374125

ACIA 2005. Arctic Climate Impact Assessment: Scientific Report. Cambridge University Press. See their graphics package of sea ice projections here.

AMAP 2017. [ACIA 2005 update]. Snow, Water, Ice, and Permafrost in the Arctic Summary for Policy Makers (Second Impact Assessment). Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme, Oslo. pdf here.

Amstrup, S.C. 2003. Polar bear (Ursus maritimus). In Wild Mammals of North America, G.A. Feldhamer, B.C. Thompson and J.A. Chapman (eds), pg. 587-610. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Amstrup, S.C., Marcot, B.G. & Douglas, D.C. 2007. Forecasting the rangewide status of polar bears at selected times in the 21st century. US Geological Survey. Reston, VA. Pdf here

Andersen, M., Derocher, A.E., Wiig, Ø. and Aars, J. 2012. Polar bear (Ursus maritimus) maternity den distribution in Svalbard, Norway. Polar Biology 35:499-508.

Arrigo, K.R. and van Dijken, G.L. 2015. Continued increases in Arctic Ocean primary production. Progress in Oceanography 136: 60-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2015.05.002

Atwood, T.C., Marcot, B.G., Douglas, D.C., Amstrup, S.C., Rode, K.D., Durner, G.M. et al. 2016. Forecasting the relative influence of environmental and anthropogenic stressors on polar bears. Ecosphere 7(6): e01370.

Castro de la Guardia, L., Myers, P.G., Derocher, A.E., Lunn, N.J., Terwisscha van Scheltinga, A.D. 2017. Sea ice cycle in western Hudson Bay, Canada, from a polar bear perspective. Marine Ecology Progress Series 564: 225–233. http://www.int-res.com/abstracts/meps/v564/p225-233/

Cherry, S.G., Derocher, A.E., Thiemann, G.W., Lunn, N.J. 2013. Migration phenology and seasonal fidelity of an Arctic marine predator in relation to sea ice dynamics. Journal of Animal Ecology 82:912-921. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2656.12050/abstract

Crawford, J. and Quakenbush, L. 2013. Ringed seals and climate change: early predictions versus recent observations in Alaska. Oral presentation by Justin Crawfort, 28th Lowell Wakefield Fisheries Symposium, March 26-29. Anchorage, AK. Abstract below, find pdf here:http://seagrant.uaf.edu/conferences/2013/wakefield-arctic-ecosystems/program.php

Crawford, J.A., Quakenbush, L.T. and Citta, J.J. 2015. A comparison of ringed and bearded seal diet, condition and productivity between historical (1975–1984) and recent (2003–2012) periods in the Alaskan Bering and Chukchi seas. Progress in Oceanography 136:133-150.

Crawford, J.A., Quakenbush, L.T. and Citta, J.J. 2015. A comparison of ringed and bearded seal diet, condition and productivity between historical (1975–1984) and recent (2003–2012) periods in the Alaskan Bering and Chukchi seas. Progress in Oceanography 136:133-150.

Crockford, S.J. 2017. Testing the hypothesis that routine sea ice coverage of 3-5 mkm2 results in a greater than 30% decline in population size of polar bears (Ursus maritimus). PeerJ Preprints 19 January 2017. Doi: 10.7287/peerj.preprints.2737v1 Open access. https://peerj.com/preprints/2737/

Crockford, S.J. 2019. The Polar Bear Catastrophe That Never Happened. Global Warming Policy Foundation, London. Available in paperback and ebook formats.

Derocher, A.E., Wiig, Ø., and Andersen, M. 2002. Diet composition of polar bears in Svalbard and the western Barents Sea. Polar Biology 25 (6): 448-452. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00300-002-0364-0

Dunbar, M.J. 1981. Physical causes and biological significance of polynyas and other open water in sea ice. In: Polynyas in the Canadian Arctic, Stirling, I. and Cleator, H. (eds), pg. 29-43. Canadian Wildlife Service, Occasional Paper No. 45. Ottawa.

Durner, G.M. and Amstrup, S.C. 1996. Mass and body-dimension relationships of polar bears in northern Alaska. Wildlife Society Bulletin 24(3):480-484.

Durner, G.M., Douglas, D.C., Nielson, R.M., Amstrup, S.C., McDonald, T.L., et al. 2009. Predicting 21st-century polar bear habitat distribution from global climate models. Ecology Monographs 79: 25–58.

Ferguson, S. H., Taylor, M. K., Rosing-Asvid, A., Born, E.W. and Messier, F. 2000. Relationships between denning of polar bears and conditions of sea ice. Journal of Mammalogy 81: 1118-1127.

Frey, K.E., Comiso, J.C., Cooper, L.W., Grebmeier, J.M., and Stock, L.V. 2018. Arctic Ocean primary productivity: the response of marine algae to climate warming and sea ice decline. NOAA Arctic Report Card: Update for 2018. https://arctic.noaa.gov/Report-Card/Report-Card-2018/ArtMID/7878/ArticleID/778/Arctic-Ocean-Primary-Productivity-The-Response-of-Marine-Algae-to-Climate-Warming-and-Sea-Ice-Decline

Garner, G.W., Belikov, S.E., Stishov, M.S., Barnes, V.G., and Arthur, S.M. 1994. Dispersal patterns of maternal polar bears from the denning concentration on Wrangel Island. International Conference on Bear Research and Management 9(1):401-410.

Gibbard, P. L., Boreham, S., Cohen, K. M. and Moscariello, A. 2005. Global chronostratigraphical correlation table for the last 2.7 million years, modified/updated 2007. Boreas 34(1) unpaginated and University of Cambridge, Cambridge Quaternary http://www.qpg.geog.cam.ac.uk/

Grenfell, T.C. and Maykut, G. A. 1977. The optical properties of ice and snow in the Arctic Basin. Journal of Glaciology 18 (80):445-463. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/igsoc/jog/1977/00000018/00000080/art00008

Hamilton, S.G., Castro de la Guardia, L., Derocher, A.E., Sahanatien, V., Tremblay, B. and Huard, D. 2014. Projected polar bear sea ice habitat in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. PLoS One 9(11):e113746.

Hammill, M.O. and Smith T.G. 1991. The role of predation in the ecology of the ringed seal in Barrow Strait, Northwest Territories, Canada. Marine Mammal Science 7:123–135.

Hare, F.K. and Montgomery, M.R. 1949. Ice, Open Water, and Winter Climate in the Eastern Arctic of North America: Part II. Arctic 2(3):149-164. http://arctic.journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/arctic/index.php/arctic/article/view/3985 Pdf here.

[see also: Hare, F.K. and Montgomery, M.R. 1949. Ice, Open Water, and Winter Climate in the Eastern Arctic of North America: Part I. Arctic 2(2):79-89. http://arctic.journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/arctic/index.php/arctic/article/view/3976 ]

Harington, C. R. 1968. Denning habits of the polar bear (Ursus maritimus Phipps). Canadian Wildlife Service Report Series 5.

Heide-Jorgensen, M.P., Laidre, K.L., Quakenbush, L.T. and Citta, J.J. 2012. The Northwest Passage opens for bowhead whales. Biology Letters 8(2):270-273. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0731

Jonkel, C., Land, E. and Redhead, R. 1978. The productivity of polar bears () in the southeastern Baffin Island area, Northwest Territories. Canadian Wildlife Service Progress Notes 91.

Kochnev, A.A. 2018. Distribution and abundance of polar bear (Ursus maritimus) dens in Chukotka (based on inquiries of representatives of native peoples). Biology Bulletin 45 (8):839-846.

Kolenosky, G.B. and Prevett, J.P. 1983. Productivity and maternity denning of polar bears in Ontario. Bears: Their Biology and Management 5:238-245.

Kovacs, K.M. 2016. Erignathus barbatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T8010A45225428. http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/full/8010/0

Lang, A., Yang, S. and Kaas, E. 2017. Sea ice thickness and recent Arctic warming Geophysical Research Letters. DOI: 10.1002/2016GL071274

Larsen, T. 1985. Polar bear denning and cub production in Svalbard, Norway. Journal of Wildlife Management 49:320-326.

Lowry, L. 2016. Pusa hispida. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T41672A45231341. http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/41672/0

Lunn, N.J., Servanty, S., Regehr, E.V., Converse, S.J., Richardson, E. and Stirling, I. 2016. Demography of an apex predator at the edge of its range – impacts of changing sea ice on polar bears in Hudson Bay. Ecological Applications 26(5):1302-1320. DOI: 10.1890/15-1256

Morrison, A. and Kay, J. 2014. “Short-term Sea Ice Gains Don’t Eliminate Long-term Threats.” Polar Bears International, “Scientists & Explorers Blog” posted 22 September 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20150509003221/http://www.polarbearsinternational.org/news-room/scientists-and-explorers-blog/short-term-sea-ice-gains-dont-eliminate-long-term-threats

Obbard, M.E., Cattet, M.R.I., Howe, E.J., Middel, K.R., Newton, E.J., Kolenosky, G.B., Abraham, K.F. and Greenwood, C.J. 2016. Trends in body condition in polar bears (Ursus maritimus) from the Southern Hudson Bay subpopulation in relation to changes in sea ice. Arctic Science 2:15-32. 10.1139/AS-2015-0027 http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/abs/10.1139/AS-2015-0027#.VvFtlXpUq50

Overland, J.E. and Wang, M. 2013. When will the summer Arctic be nearly sea ice free? Geophysical Research Letters 40: 2097-2101.

Perovich, D., Meier, W., Tschudi, M.,Farrell, S., Hendricks, S., Gerland, S., Haas, C., Krumpen, T., Polashenski, C., Ricker, R. and Webster, M. 2018. Sea ice. Arctic Report Card 2018, NOAA. https://www.arctic.noaa.gov/Report-Card/Report-Card-2018

Pilfold, N. W., Derocher, A. E., Stirling, I. and Richardson, E. 2015 in press. Multi-temporal factors influence predation for polar bears in a changing climate. Oikos. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/oik.02000/abstract

Polyak, L., Alley, R.B., Andrews, J.T., Brigham-Grette, J., Cronin, T.M., Darby, D.A., Dyke, A.S., Fitzpatrick, J.J., Funder, S., Holland, M., Jennings, A.E., Miller, G.H., O’Regan, M., Savelle, J., Serreze, M., St. John, K., White, J.W.C. and Wolff, E. 2010. History of sea ice in the Arctic. Quaternary Science Reviews 29:1757-1778.

Regehr, E.V., Laidre, K.L, Akçakaya, H.R., Amstrup, S.C., Atwood, T.C., Lunn, N.J., Obbard, M., Stern, H., Thiemann, G.W., & Wiig, Ø. 2016. Conservation status of polar bears (Ursus maritimus) in relation to projected sea-ice declines. Biology Letters 12: 20160556. http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/12/12/20160556 Supplementary data here.

Regehr, E.V., Hostetter, N.J., Wilson, R.R., Rode, K.D., St. Martin, M., Converse, S.J. 2018. Integrated population modeling provides the first empirical estimates of vital rates and abundance for polar bears in the Chukchi Sea. Scientific Reports 8 (1) DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-34824-7 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-34824-7

Richardson, E., Stirling, I. and Hik, D.S. 2005. Polar bear (Ursus maritimus) maternity denning habitat in western Hudson Bay: a bottoms-up approach to resource selection functions. Canadian Journal of Zoology 83: 860-870.

Rode, K. and Regehr, E.V. 2010. Polar bear research in the Chukchi and Bering Seas: A synopsis of 2010 field work. Unpublished report to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior, Anchorage. pdf here.

Rode, K.D., Douglas, D., Durner, G., Derocher, A.E., Thiemann, G.W., and Budge, S. 2013. Variation in the response of an Arctic top predator experiencing habitat loss: feeding and reproductive ecology of two polar bear populations. Oral presentation by Karyn Rode, 28th Lowell Wakefield Fisheries Symposium, March 26-29. Anchorage, AK.

Rode, K.D., Regehr, E.V., Douglas, D., Durner, G., Derocher, A.E., Thiemann, G.W., and Budge, S. 2014. Variation in the response of an Arctic top predator experiencing habitat loss: feeding and reproductive ecology of two polar bear populations. Global Change Biology 20(1):76-88. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.12339/abstract

Rode, K. D., R. R. Wilson, D. C. Douglas, V. Muhlenbruch, T.C. Atwood, E. V. Regehr, E.S. Richardson, N.W. Pilfold, A.E. Derocher, G.M Durner, I. Stirling, S.C. Amstrup, M. S. Martin, A.M. Pagano, and K. Simac. 2018. Spring fasting behavior in a marine apex predator provides an index of ecosystem productivity. Global Change Biology http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.13933/full

Rode, K.D., Wilson, R.R., Regehr, E.V., St. Martin, M., Douglas, D.C. & Olson, J. 2015. Increased land use by Chukchi Sea polar bears in relation to changing sea ice conditions. PLoS One 10 e0142213.

Smith, M. and Rigby, B. 1981. Distribution of polynyas in the Canadian Arctic. In: Polynyas in the Canadian Arctic, Stirling, I. and Cleator, H. (eds), pg. 7-28. Canadian Wildlife Service, Occasional Paper No. 45. Ottawa.

Stern, H.L. and Laidre, K.L. 2016. Sea-ice indicators of polar bear habitat. Cryosphere 10: 2027-2041.

Stirling, I. 1974. Midsummer observations on the behavior of wild polar bears (Ursus maritimus). Canadian Journal of Zoology 52: 1191-1198. http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/abs/10.1139/z74-157#.VR2zaOFmwS4

Stirling, I. 2002. Polar bears and seals in the eastern Beaufort Sea and Amundsen Gulf: a synthesis of population trends and ecological relationships over three decades. Arctic 55 (Suppl. 1):59-76. http://arctic.synergiesprairies.ca/arctic/index.php/arctic/issue/view/42

Stirling, I. and Andriashek, D. 1992. Terrestrial maternity denning of polar bears in the eastern Beaufort Sea area. Arctic 45:363-366.

Stirling, I., Andriashek, D., and Calvert, W. 1993. Habitat preferences of polar bears in the western Canadian Arctic in late winter and spring. Polar Record 29:13-24. http://tinyurl.com/qxt33wj

Stirling, I., Calvert, W., and Andriashek, D. 1984. Polar bear ecology and environmental considerations in the Canadian High Arctic. Pg. 201-222. In Olson, R., Geddes, F. and Hastings, R. (eds.). Northern Ecology and Resource Management. University of Alberta Press, Edmonton.

Stirling, I. and Cleator, H. (eds). 1981. Polynyas in the Canadian Arctic. Canadian Wildlife Service, Occasional Paper No. 45. Ottawa.

Stirling, I, Cleator, H. and Smith, T.G. 1981. Marine mammals. In: Polynyas in the Canadian Arctic, Stirling, I. and Cleator, H. (eds), pg. 45-58. Canadian Wildlife Service Occasional Paper No. 45. Ottawa. Pdf of pertinent excerpts from the Stirling and Cleator volume here.

Stirling, I, Kingsley, M. and Calvert, W. 1982. The distribution and abundance of seals in the eastern Beaufort Sea, 1974–79. Canadian Wildlife Service Occasional Paper 47. Edmonton.

Stirling, I. and Derocher, A.E. 2012. Effects of climate warming on polar bears: a review of the evidence. Global Change Biology 18:2694-2706 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02753.x/abstract

Stirling, I. and Øritsland, N. A. 1995. Relationships between estimates of ringed seal (Phoca hispida) and polar bear (Ursus maritimus) populations in the Canadian Arctic. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 52: 2594 – 2612. http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/abs/10.1139/f95-849#.VNep0y5v_gU

Stroeve, J., Holland, M.M., Meier, W., Scambos, T. and Serreze, M. 2007. Arctic sea ice decline: Faster than forecast. Geophysical Research Letters 34:L09501. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2007GL029703

SWG [Scientific Working Group to the Canada-Greenland Joint Commission on Polar Bear]. 2016. Re-Assessment of the Baffin Bay and Kane Basin Polar Bear Subpopulations: Final Report to the Canada-Greenland Joint Commission on Polar Bear. +636 pp. http://www.gov.nu.ca/documents-publications/349

Walsh, J.E., Fetterer, F., Stewart, J.S. and Chapman, W.L. 2017. A database for depicting Arctic sea ice variations back to 1850. Geographical Review 107(1):89-107. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2016.12195.x

Wang, M. and Overland, J. E. 2012. A sea ice free summer Arctic within 30 years: An update from CMIP5 models. Geophysical Research Letters 39: L18501. doi:10.1029/2012GL052868

Wang, M. and Overland, J.E. 2015. Projected future duration of the sea-ice-free season in the Alaskan Arctic. Progress in Oceanography 136:50-59.

Whiteman, J.P., Harlow, H.J., Durner, G.M., Anderson-Sprecher, R., Albeke, S.E., Regehr, E.V., Amstrup, S.C., and Ben-David, M. 2015. Summer declines in activity and body temperature offer polar bears limited energy savings. Science 349:295-298.

Completely bored of the endless polar bear stuff, EXCEPT when it’s from Susan Crockford. 😉

Yes, very informative. Many thanks.

Ditto. Answers a question I had on another recent thread superbly. Keep up the great work Susan.

instead of a wetland comparison, which would work, a more apt one might be a Vernal Pool.

a vernal pool is a depression in the ground that annually floods, does not have a natural outlet, stays wet for at least 3 months, and dries out every summer, only to come back the following spring thaw for ~3 months. a vernal pool CAN be part of a wetland, but in and of itself, it is not a wetland.

rare and endangered species live in these pool areas, and breed etc when the pool is active.

sea ice… melts in the summer to a certain extent, then always comes back in the winter.

Not sure that’s such a good analogy … since the EPA wants to seize Federal control of all lands which contain Vernal Pools … designating them as “wetlands”. If the EPA catches wind of your analogy … they’ll seize control of the entire Arctic … and restrict all human use of it. Oh, and will mandate we “transform” our entire economic system to prevent ANY changes to the Arctic.

Oh! I forgot a little back-up for my “opinion” …

https://www.capitalpress.com/state/california/ranch-owners-to-pay-million-for-destroying-vernal-pools/article_0b39af78-207f-59c0-8a14-928d7db71fd7.html

It would appear that models handle polar bears and ice about as well as models handle clouds. The amount of assured claims seen inverse to their actual knowledge.

moderators, Griff has tried to slander Dr Crockford in the past by inpuning both her credentials and her motivation. I ask you to not allow him to comment on this post (frankly he should Be banned in general).

(He is in Moderation bin, his comments REQUIRE approval by a Moderator) SUNMOD

I disagree about banning Griff – it’s always hilarious to see him get stomped all over on the comments here.

Did you read his slander against Dr Crockford or Dr Soon?

I saw the whole thing. Griffie ended up looking like a fool. So let him speak. Dr. Crockford is tough enough to take anything Griff would send her way.

I did read Griff’s slanderous attacks, but I still feel that ridicule is the best defence

Griff loves the humiliation, and deserves it. Let Griff range free. 😇

I’ll fill in for Griff.

“Facts, facts, facts. How tiresome. Especially when Dr. Crockford has been thoroughly discredited. I estimate her credit rating as 487, which wouldn’t get her a layaway deal at Walmart. That’s just my estimate, of course, based on no data whatsoever. But don’t be a denier of it, just don’t. Besides, everything she says here has been completely debunked, though some of it was rebunked, but subsequently thoroughly debunked again. Don’t even try replying to this post, you racist, fascist deniers. Don’t even try…”

Hows that?

Good try, but not nearly idiotic and nasty enough.

I don’t think a lot of people realize that 4 million k/sq….is the size of 4 Egypts…and it’s huge

Thank you Susan for your continued commitment to the truth. I wonder how much sea ice there was in the Arctic 4-6Kya when the sea levels were 6 feet higher. I would bet not much.

Thank you, Susan, for the post & thanks, CTM, for cross posting it.

Regards,

Bob

The epitome of an argumentative dispassionate secondary scientific paper. Your refutations are void of color commentary and the acid overtone scent of “you’re wrong, I’m right” phrases we soooo often see in scientific primary, secondary, and tertiary publications from scientists at all levels of notoriety.

I am reminded of my first attempt at writing up the results of my auditory brain stem research. I was terribly excited about the discoveries and without thinking, wrote in a style that exuded that excitement. Needless to say, the seasoned scientists who edited my attempts covered it with red marks, telling me, almost exasperated by repeating it, to remove the color commentary. Even to the point of Dr. Rappaport exclaiming that I was not writing about a football game in which my team was winning!

Anyway, Dr. Crockford, you are an inspiration.

Thanks for that Pamela – and all others above and below for their positive feedback.

Susan

re. Josh’s cartoon

Under no circumstances does a seal smile in the presence of a polar bear. Under no circumstances do I smile if there’s a polar bear within a mile. I hate polar bears. It’s amazing how invisible they are against the white landscape under whiteout conditions.

“Under no circumstances do I smile ” when there is a commie around.

Is that you, in the lower left, with goggles and breathing tube?

Perhaps based on the look of a Golden Retriever.

Bob – – it is a cartoon.

On the one hand, you are right, it is a cartoon.

On the other hand, there is Disneyfication. The word has many meanings but one refers to giving people a totally twisted view of nature. The Earth goddess Gaia would just as soon kill you as look at you. You wouldn’t know that if your whole experience of the outdoors came from Disney.

Two dated words: Chilly Willy.

I’ve always hated when that happens.

What’s really unrealistic is the bear sunning itself buried in the sand.

Polies overheat easily.

Alarmists have never explained how Polar Bears survived the Minoan, Roman and Medieval Warm Periods and yet are going extinct now.

……..and the Holocene Optimum.

Those didn’t happen the world before 1950 was always optimum ….. explained.

Before AD 1979 was Eden and perfect!

And the Eemian Interglacial, in which we now know that their ancestors existed, grizz having already started specializing on hunting ringed seals in their birthing lairs.

Polar bear jawbone from the Eemian of Svalbard:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7132220.stm

Polar bears in the British Isles during the last glaciation, possibly even its maximum:

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/earth/wildlife/8622987/Polar-bears-traced-back-to-Britain.html

The species has no problem with conditions warmer than now, as during the Eemian, or much colder, as during the Last Glacial Maximum and other of the deepest cold spells of the last “ice age”.

Maybe the biggest fallacy about Arctic sea ice is the assumption that its year to year changes are driven by global warming.

https://tambonthongchai.com/2018/08/04/does-global-warming-drive-changes-in-arctic-sea-ice/

Only cuddly polar bear is the stuffed one

Perhaps one of these:

https://www.bearskin-rugs.com/polar-bear-rugs-c-62.html

Another excellent report by Dr. Susan, complete with references and videos. The only thing I missed was a reference to the penguins.

Here’s some actual observations from July/August 1964: Sea ice had retreated to, maybe, four or five nautical miles off shore from Point Barrow. By late August the sea ice had advance again to within a mile or so of the shore line.

Now that we have heard about some of the tricks the BBC camera people get up to in order to obtain a dramatic scene, I am a bit suspicious of that video of the hunt , although I have seen it before or something similar. How did they get such close pictures without disturbing seal or bear? And now that I have seen it again I wonder about the sea ice thickness. A bear must weigh more than 350kg surely , and heaving itself up must stress the ice, but nothing breaks off at the edge, at least not that I could see. Mind you my knowledge of sea ice properties is virtually zero , we don’t get a lot of it in Cheshire.

@ 7:38 am Steve K asked: “when the sea levels were 6 feet higher”

At the apex of the last glacial advance the oceans were quite a bit lower and the environment would have been different.

Is there a report that covers this period with respect to sea surface and ice/bear/seal interaction?

Perhaps the bears came south along the (then) coast and found Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds (of that time) to their liking.

Another excellent summary by Dr. Susan Crockford on the viability, fecundity, and feeding habits of polar bears, given the natural variations in polar climates.

Thanks CTM, for reposting it here!

Meanwhile the WWF still regularly invite gullible folk to donate money to help save the polar bear.

We should all keep in mind that arctic sea ice was around before 1979, which happened to be a year with a lot of sea ice, since the 1970’s was the decade where climate scientists were stressing out over whether the Earth was going into another ice age. It was real cold then, and consequently arctic sea ice coverage was high.

So comparing arctic sea ice today to the amounts in 1979 gives a distorted picture of arctic sea ice. We should be comparing today to the days back in the 1930’s when it was comparitively warm and the arctic sea ice was comparitively low.

The reason we usually start with 1979 is that is the year when satellites first started making measurements of arctic sea ice (there were some earlier satellite measurements but not much earlier), which is also convenient for the alarmists since 1979 is about the coldest period since the 1930’s, so they can claim that CAGW is causing the temperatures to warm and the arctic to melt. CAGW didn’t cause the temperatures to warm and the arctic to melt during the 1930’s, so CAGW may not be causing the current warming or melting, either since both are similar in magnitude.

The lowest levels of arctic sea ice in recent history were during the 1930’s. That is what we should be comparing to the arctic of today, not to the coldest period since 1910 (1979). Unfortunately, we don’t have satellite data for the 1930’s, so the alarmists get to distort the data by ignoring history. There are lots of newpaper accounts about the arctic back in the 1930’s. The alarmists can’t erase them.

There are also maps of sea ice, whose methods can be reproduced now.

And the fact that during the late ’30s and early ’40s, the Northern Sea Route along the Siberian coast was open in summer, as it usually is now. But from the late ’40s to late ’70s (and later), it was closed. Hence the Soviet interest in nuclear-powered ice breakers in the ’50s and ’60s.

No kidding, I love animals and our house is an always open shelter for whatever stray pet seeks a new loving home. No one takes pride in that, we are just delighted when a new companion joins in.

However. Reality check: -What is the real utility of polar bears ? Very few of them are domesticated, most are potentially hazardous to men. Not the kind of beast to purr on your pillow or come along for a walk.

Pets play a huge social role. They are often the only alternative to terminal loneness to many.

However not because they are white and fluffy that polar bears are lovely creatures, always ready to cuddle and play with the kids. No siree.

Which does not mean that we have to rifle them all out. To the opposite. Just let them in peace, where they are and have been long before us. And were commercially harvested till the late seventies for their fur and meat.

Don’t try to turn them into a symbol of cuteness or whatever other guilt inducing public relations associate.

Polar bears are finely tuned predators without any positive contribution to our survival or influence on our eventual extinction.

Without polies, we’d be overrun by nasty ringed seals!

I was in Anchorage a few weeks ago, and the crazies were holding a climate change rally downtown. I was there photographing the beautiful flower gardens in full bloom, and I was approached by two college girls asking me to send a postcard to Murkowski urging her to save the polar bears. I told them the bears are fine and their numbers are increasing, and I told them if the bears were truly endangered they should petition the Canadian government to stop issuing hunting permits. The girls sheepishly admitted that they knew the numbers are increasing, but that the bears could still use our help. I them asked them why they were not helping the humans who are starving to death by the millions instead, and they just walked away.

Excellent ! + 1k !

Id amo !

I never get bored with learning,especially when one can fact check all the way through

Polar bears are ok for now, agreed. But the summer sea ice does appear to be in trouble ? The downward trend is not going away

The downward trend in arctic sea ice reversed after the 1930’s warmth. There is no reason to assume current declines in arctic sea ice will continue. The current global temperature is down about 0.5C from the highpoint of the El Nino year of 2016.

It generally doesn’t go away this time of the year andy. Yes, it would be nice for slapping down climate idiots if it ended up above 2018, ergo 2007, but the trend from 2007 will still be positive (slightly) anyway.

The downward trend is not going away

If the ice disappeared completely (it won’t), obviously both both bears & seals would be on land (seals need land or ice too).

It has already gone away, unless there should be another freak WX year with two August Arctic cyclones, which events account for the lows of 2007, 2012 and 2016. The trend in summer minimum is flat since 2007 and up since 2012.

From 1979 to 2012 in the dedicated satellite record, a new, lower low was made at least every five years. Since 2012, there has not been a new low.

If CO2 were the cause of Arctic sea ice decline after 1979, then how to explain the increase in Antarctic sea ice from 1979 to 2014?

Sea ice extent is cyclic. Its fluctuations have nothing to do with man-made CO2.

Andy,

Polar bears don’t need summer sea ice. What matters to them is land-fast ice in the early spring, on which ringed seal moms make their snow lairs in which to raise their young, maintaining diving holes through the ice with their impressive claws.

I saw an advertisement a couple of days ago from the WWF saying that Arctic sea ice is declining and it is leading to a reduction in polar bear numbers; send us your money.

I’m sure that there will be many people who believe anything NGOs like the WWF publish and some, I expect, will donate.

Is there no regulation of what these bodies can publish for the general public to read, or does it require individuals to follow a convoluted complaint procedure, even when complaints are upheld, the damage is done?

“I saw an advertisement a couple of days ago from the WWF saying that Arctic sea ice is declining and it is leading to a reduction in polar bear numbers; send us your money.”

That sounds like WWF is trying to defraud the public by asking them to send money to fix a problem that doesn’t exist..

I thought I read recently that West Hudson Bay ice was now breaking up in spring 2 weeks LATER than in the 1980s. Can anyone clarify please?

From Susan’s site:

https://polarbearscience.com/2018/11/10/w-hudson-bay-freeze-up-earlier-than-average-for-2nd-year-in-a-row-polar-bear-hunt-resumes/

Thank you John Tillman.

That covers the start of the ice season. I have now found a report on Climate Depot that there has been no trend in spring breakup dates for 20 years.