Guest Post by Willis Eschenbach

It’s been a while since I played “Spot The Volcano”. The premise of the game is that the decrease in temperatures from volcanic eruptions is nowhere near as large as people claim. So I ask people to see if they can identify when a volcano erupted based on the temperature records of the time.

Now, I say that the main reason the temperature drop from volcanic eruptions is so small is that when we get a reduction in downwelling radiation from any cause, the equatorial oceans start to cool. When that happens the clouds form later in the day, allowing in more sunshine. And the net result is that any cooling from the volcanic eruption is mostly offset by the increase in incoming solar energy.

With that in mind, I thought I’d take a look to see what records we have for the largest volcanic eruption in modern times. This was the eruption of the Indonesian island of Tambora in April of 1815. To my surprise, I found that we have no less than forty-two temperature records from that time. As you might imagine, most of these are from Europe. The list of the forty-two stations is appended in the end-notes.

So I took the records for the period during which the Tambora eruption occurred, and I “standardized” them so that they all had an average value of zero and a standard deviation of one. Then I plotted them all on one graph. Here is that result.

Figure 1. Temperature records of forty-two temperature stations for a period during which the Tambora eruption occurred. Seasonal variations have been removed from the data, leaving only anomalies. DATA SOURCE

As you can see, there is good agreement between the various records, with the cold and warm years affecting most if not all of the records. And if that’s too fuzzy for you, here is the same data with the average of all forty-two of the stations overlaid in red on the individual station records.

Figure 2. As in Figure 1, but with the average overlaid in red.

You can see the problem. The largest eruption in modern times, and it is absolutely not obvious when it happened …

So when was the eruption? Well, it’s not where you’d expect, which would be just before one of the two biggest drops in temperature, shown on the left-hand side of the graph. Nor is it where the big temperature drop is on the far right of the graph. Nope. It’s in a very generic area where you’d never expect it to be found …

Figure 3. As in Figure 1, but with the years added.

Now, there are a couple things of note here. First, there are a number of temperature drops even in only this short record which are much larger than the temperature drop after the Tambora eruption.

Second, there are a number of cold temperature excursions even in this short record, some of which are much colder than during the period after the eruption.

My conclusion from this? Yes, there were likely areas in Europe and the US which were somewhat colder than usual after the Tambora eruption. But temperatures somewhat colder than usual occur every few years …

And overall, despite the size of the eruption, despite the megatonnes of sulfur dioxide that the eruption sent up into the stratosphere, despite the reduction in sunlight from that stratospheric dimming … despite all of that, the effect on temperature was indistinguishable from natural fluctuations in other parts of the record.

My very best to everyone,

w.

PS—As is my custom, I ask that when you comment you quote the exact words you are discussing, so that we can avoid at least some of the misunderstandings that plague the intarwebs.

DATA NOTES:

The following records were used in this analysis:

Basel Binningen, Switzerland

Berlin-Dahlem, Germany

Berlin-Tempel, Germany

Bologna Borgo, Italy

Budapest, Hungary

Chalons, France

De Bilt, Netherlands

Edinburgh Royal Obs., UK

Gdansk-Wrzeszcz, Poland

Geneve-Cointr, Switzerland

Gordon Castle, UK

Greenwich Maritime Muk, UK

Hohenpeissenb, Germany

Innsbruck University, Austria

Karlsruhe, Germany

Kobenhavn, Denmark

Kremsmuenster, Austria

Leobschutz, Czech Republic

Madras Minamb, India

Manchester Ai, UK

Milano Linate, Italy

Montdidier, France

Munchen Riem, Germany

New Haven Tweed, United States

Nice, France

Palermo, Italy

Paris Le Bourget, France

Praha Ruzyne, Czech Republic

Regensburg, Germany

St.Peterburg, Russia

Stockholm, Sweden

Strasbourg, France

Stuttgart, Germany

Torino Casell, Italy

Torneo, Finland

Trondheim Tyholt, Norway

Udine Campoformido, Italy

Vilnius, Lithuania

Warszawa-Okec, Poland

Wien Hohe War, Austria

Woro, Finland

Wroclaw Ii, Poland

Discover more from Watts Up With That?

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Willis, very interesting and thought stimulating, as usual. My guess is that weather and climate are very complex and every major volcanic eruption is a bit different. I’m afraid we just don’t have enough detailed measurements from enough large eruptions to really be confident one way or the other about how much impact major volcanic eruptions have on both weather and climate.

Wasn’t that during the Dalton Minimum? What else was going on to cause the Minimum? This gets back to maybe there are a lot more inputs into the climate system than just Tambora, although your point of the temperatures don’t seem to fluctuate out of the “normal range for the 10 year period” appears to be valid.

There does appear to be a short .5 deg drop for over a year after the eruption which may or may not be relevant.

“There does appear to be a short .5 deg drop for over a year after the eruption which may or may not be relevant.”

Yes, I noticed that. In fact the drop lasts for almost two years. The other relatively long-term drop, centred on 1812, lasted only about a year.

The two cold spikes only last a couple of months. More smoothing of the graph would help to remove the short term effects.

It may be coincidence, but there does appear to be a nearly two year cooling following the eruption, and nowhere else in the graph is there a similar long-term cooling.

Chris

Your Fig 3 is very interesting. There was so much variability from other causes, any effect of Tambora was lost in the clutter.

1809-1810 was very cold, which is usually ascribed to the “mystery eryption” of 1808/09, known from sulphate deposits in glaciers, but not definitely identified. Contemporary observations of “dry fog” in South America suggests that it was somewhere in the Western Pacific.

Seems we could narrow down the location of that “mystery eruption” by taking those British ships logs (referenced elsewhere) and plotting their routes around that time, and look for evidence of an eruption in places where the ships didn’t go. You think?

You have missed several long records. Lund and Uppsala in Sweden for example.

The very long (from 1722) Uppsala series is available here:

http://www.smhi.se/polopoly_fs/1.2866!/uppsala_tm_1722-2018.zip

Reference: Bergström, H., and Moberg, A.: 2002, Daily air temperature and pressure series for Uppsala 1722-1998. Climatic Change, 53, 213-252.

Note that the 1999-2018 section is probably not corrected for UHI. It is an interesting record since it is one of the few that covers most of the very warm 1715-1740 interval just after the end of the Maunder minimum,

Thanks, tty. I’ll add that record. For some reason it’s not in the GHCN data. I suspect it’s because it’s created out of six different temperature records. Here’s the relevant section.

The dataset contains two versions, one adjusted for UHI and one unadjusted. Long-term trend is 0.026°C/decade unadjusted, 0.022°C/decade adjusted for UHI.

Bizarrely, post 1999 the trends difference is reversed. Unadjusted is 0.237°C/decade, adjusted for UHI is 0.239°C/decade.

w.

The adjustment before 1999 was made by Bergström and Moberg, the adjustment from 1999 by SMHI, the Swedish equivalent of NOAA. Nuff said.

He also missed Armagh Observatory.

Your charts are unlabled on the horizontal (time) axis. Knowing you, I expect this is not an accident.

How long a time period are we looking at?

oops — scanning quickly, I missed the very last chart.

Here is wiki on the eruptions presumed affects https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Year_Without_a_Summer

It looks like New England USA was where most cold weather was experienced. Unfortunately there is only one US datapoint in this data

Ok, then why did UAH show temperature drops that coincided very well with the El Chichón and Mount Pinatubo eruptions last century?

Thank, rah. Same problem.

w.

Willis,

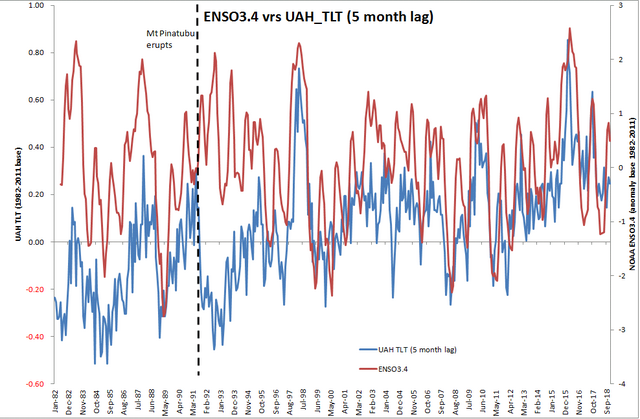

One noticeable thing about UAH TLT is that it closely follows the ups and downs of ENSO3.4 with a ‘best fit’ long term lag of ~ 5 months (TLT following ENSO). I could only find monthly ENSO3.4 data starting Jan 1982, so I compared this with UAH TLTv6 over the period since. I converted both data sets to their 1982-2011 anomaly base to bring the numbers closer together for charting purposes and made this chart:

There is generally very good agreement between UAH and ENSO3.4 with this 5-month lag (except for trend, as ENSO is trendless), but the various fluctuations in ENSO are closely matched by UAH after ~5 months with one notable exception: the June 1991 Mt Pinatubo eruption in the Philippines (indicated by the vertical dashed line).

The TLT response to this was immediate and sent lower troposphere temperatures in the exact opposite direction of the ENSO signal it would normally have followed. The tight correlation between ENSO and TLT doesn’t really pick up again for a couple of years. DOesn’t this suggest that, as far as the lower troposphere is concerned at least, large eruptions can and do have an immediate and fairly long term impact on temperatures?

NOAA ENSO data here: http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/data/indices/sstoi.indices

DWR54 and Willis,

DWR54 has a very good point. Interannual temperature variations are dominated by ENSO signals. In order to see volcano effects on temperatures, one needs to remove the ENSO signal or compare the ENSO signal to global temperature signals. I have taken a preliminary look at the HadCRUT4 detrended temperature compared to the Multivariant ENSO index. You can see how El Chichon eruption in 1982 reduced the temperature anomaly of the 1983 super El Niño. Mt. Pinatubo eruption in 1991 resulted in a global temperature cooling from 1992-1994 during El Niño conditions.

https://imgur.com/BUpGjGg

Willis,

As I recall, your same analysis of major eruption events over the past two centuries showed the same lack of impact on global temperatures.

I’m curious how you explain the historical accounts of a “year without a summer”? Was it not a real event? Was it real but less a matter of cold than some other weather conditions impacting agriculture?

Rich, I suspect we’re seeing three things here.

First, certain individual locations have larger effects from any given volcanic eruption.

Second, we humanoids tend to exaggerate the weather of the past … “Why, when I was a boy, we had six feet of snow in one storm!” and the like.

Third, even one untimely frost can wipe out an entire growing season.

w.

Well yeah, in the summer we sometimes had as little as six feet!

I think what I read was that there was an excessive amount of rain in 1816.

I’m just a character out here in the Peanut Gallery, but wouldn’t “excessive amount of rain” be something consistent with elevated particles in the atmosphere? Something for the water vapor to bind to and form rain?

Yes, I thought that, too, AGW.

I learned in my Indiana history lessons about 1816, “the year without a summer,” during which hardly any crops were harvested because there were freezes in every month, and snow fell at least somewhere in the territory in every month. That was the year that Indiana came up for a vote in Congress (in December, I believe) as to whether it would become a state. According to my memories of what I learned then, the vote was in favor, but doubts were expressed whether anyone would want to live in a state where one could not plant crops. Of course, in subsequent years the weather returned to more typical conditions, and no one worried about Indiana’s being asked to resign from the Union on account of the weather. All of this was anecdotal, of course, so I did not register shock that you failed to list the Corydon, IN, weather station among your data (Corydon, a tiny village then and now, likely without any weather station, was the first capital of the state; Indianapolis was founded and built later).

Willis, Rich:

It’s been a while since I looked into it, so I’m going from memory here, but the key thing about the “year without a summer” was not consistently low temperatures. Instead, at least in North America, there was an unusually late killing frost in the spring, and then an unusually early killing frost in the autumn.

As Willis says, this “can wipe out an entire growing season”.

Ed, your timing is good. I’m looking at this in my next post, publishing tomorrow 10AM Pacific Time.

w.

“I’m curious how you explain the historical accounts of a “year without a summer”?”

Sometimes people make mountains out of molehills, like, y’know, CO2 and climate sensitivity.

The point is the temperature recovered extraordinarily quickly. That observational fact has the following implications. (Basic control theory. System response to a step change to determine system parameters.)

The volcanic eruption causes a step change in temperature. The earth’s response to the step change is to resist change (this is called negative feedback in control theory) as opposed to positive which would amplify change.

If the earth amplified temperature forcing changes (positive feedback) there would be an oscillating response for decades.

The fact that there was not an oscillating temperatures for years supports the assertion that the earth’s response to forcing change is strongly negative. i.e. The earth resists temperature changes by changes in cloud cover.

CAGW requires positive feed back to amplify.

Excellent point, William. We exist here on this planet because it is a homeostatic system. Essentially every change is resisted (damped) rather than amplified.

I assume that Willis takes an interest in this topic because volcanoes are frequently invoked as the deus ex machina for why 20th century temperatures don’t correlate well with CO2 concentration. If volcanoes have a smaller and shorter-lived impact than has been claimed, then the CAGW believers still have a lot of splainin’ to do.

Excerpts: Rich Davis – January 26, 2019 at 10:44 am

The BIG question is, …… which do you trust to be the most accurate/believable, …… the various historical temperature records ….. or ….. the historical accounts of weather conditions?

“HA”, we all know that we cannot trust the accuracy of the contents of the US Temperature Record (1870 to present).

ok, Willis, maybe the effects of a large volcanic eruption are lost in normal year-over-year variation, but you, like most everyone else, have been seduced by flashy, large pyroclastic one-volcano eruptions (like Tambora, Krakatoa, Vesuvius, etc.). But the volcanos that have an impact on climate are the large basalt flow provenances, like Deccan Siberia, and Columbia River. Not only is the temperature of the basalt flows much higher, and the geographic area affected very much greater, but the real secret is what I described in the comment “Geologists, Pizza, Beer”. This relates how a local hermit living on the Panamint Valley side of the Panamint Mountains (the other side is Death Valley), asked us to bring back from town two frozen pizzas and some beer. When we returned he said open some beers and give me one of the frozen pizzas, which he proceeded to set on a large black basalt boulder. The pizza was cooked by the time we were half-way through the beer. The temperature of the black basalt boulder must have been upwards of 160 deg F. Think about 100,000 square kilometers of black basalt flows, functioning like a black body, for hundreds of years. You can’t get those kind of results (cooling, that is) from those pretentious pyroclastic noisy events.

Ron,

Maybe I’m as dense as your basalt, but I’m not sure that I see what you’re trying to say here. Are you agreeing with Willis that volcanoes have a weak and transient cooling effect from dimming insolation but claiming that their bigger impact on climate is their strong and enduring warming effect from reduced albedo?

Sorry. I’ll try again with link this time. Why did UAH show drops in temperature that coincided very well with the El Chichón and Mt. Pinatubo eruptions last century?

It is easy to say “coincided well” but what does that means explicitly in scientific terms.

The Mt P cooling actually started well over a year before the eruption, so clearly some other effect is being confounded with it. If the cooling is exaggerated by confounding with other changes at about the same time you will think that climate sensitivity is greater. You will them be able to ramp the GHG warming to counter it in your models.

This is exactly what Hansen et co. did post Y2K when they abandoned the physics based values they got from analysing data after El Chichon and just started tweaking stuff to improve their model hindcasts.

How did the El Chichón and Pinatubo volcanic eruptions affect global temperature records?

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2009/01/13/how-did-the-el-chicon-and-pinatubo-volcanic-eruptions-affect-global-temperature/

But didn’t Tambora cause the year without a summer?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Year_Without_a_Summer?

If your theory is correct, shouldn’t you be able to see the effect in modern satellite data? I think Pinatubo caused global cooling. Is there data on tropical cloud formation that you could compare before, during and after the Pinatubo cooling?

Pinatubo sure did cause a red sun at midday in where I live in Indiana and as I remember considerably cooler temps.

It also caused incredibly beautiful deep purple “sunsets” on Oahu over an hour after the sun dipped below the horizon. I did not expect it and hadn’t brought my camera to the picnic dinner I had taken my kids to.

Yes. I would suggest that the record is inadequate, Tambora erupted during an already cool period, and temperature is important, but lack of sunlight and precipitation in the form of snow and hail can be devastating to crops.

But didn’t Tambora cause the year without a summer? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Year_Without_a_Summer?

If your theory is correct, shouldn’t you be able to see the effect in modern satellite data? I think Pinatubo caused global cooling. Is there data on tropical cloud formation that you could compare before, during and after the Pinatubo cooling?

What level of accuracy do we have about the amount of CO2 released, by black smokers, and other ocean bottom vents, and how many active submarine volcanos are emitting gases continuously?

Lars

All of them are.

Funny +1

At 8.2S lat I’d expect it to take 12 months to show up in a mid-Lat NH record. and then not as a spike in an 11 yeat long graphical presentation but as a 12 minth trend.

The spikes (up and down) are month long events in Willis’ 11 years of data graph.

What about Southern Hemisphere temps or temps in the vicinity of the eruption?

How would this look if you just the closest data site, Madras Minamb, India?

Also there’s no records for the Southern Hemisphere, given Tambora is located there.

Thomas Jefferson made daily temperature measurements at Monticello from 1810 to 1816. During 1816 he measured the temperature decline known as the “Year Without a Summer” and the “Poverty Year.” He was apparently unaware of the 1816 Tambora eruption and offered no other explanation for the decline, which was associated with exceptionally cold temperatures in New England and elsewhere. I measured a modest noon temperature decline in Central Texas following the 1992 Pinatubo eruption, which was associated with a sharp increase in the aerosol optical depth. The peak noon temperature in 1990 was 96.8F, which fell to 94.0F in 1992. The temperature then recovered almost linearly until 1996, when it peaked at 100.4 F. A similar trend in minimum noon temperature occurred during these years. I’ve made near daily measurements since 4 Feb 1990 and have not observed a similar association of temperature with high optical depth since Pinatubo. I have also observed various ups and downs in temperature not associated with volcanism that Willis has described. My conclusion: (1) Major volcano eruptions can indeed reduce temperature and (2) so can weather events beyond our control.

Jefferson was always recording weather and temp when he was at home. The Christmas night 1776 when Washington and his little Army crossed the Delaware to attack Trenton, Jefferson recorded 8″ of snow fell at Monticello.

He nicknamed his thermometer Sally. His wife would ask, are you going out to check Sally again?

Apparently he did partake in taking Sally’s temperature.

But to be historically correct, Jefferson was widowed in 1982 when Martha died. He likely didn’t begin his “fatherly” relations with then 15 yr old Sally until 1788 when she was with him in France when he was the US Ambassador there.

widowed in 1782 of course (not 1982). I miss edit, sigh.

Thanks, nice to know.

Sally Hemmings was Martha Jefferson’s half sister, ie Thomas’ half sister in law.

Yes, he even bought a new thermometer during deliberations of the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia. The 1810-1816 segment was considered his best. He converted the data into a table that I plotted to see the Year Without a Summer effect.

Tambora’s main VEI 7 eruption was 10 April 1815. It would take at least 6 moths for the higher lats of the NH to see an effect of diminished insolation there. The oceans buffer (largely prevent) short term temperature swings between hemispheres.

I had read about the “Year Without a Summer” so long ago, it is best to update.

So, rather than finding some of my old books with references to Tambora and the ensuing summer frosts, I went to Wiki.

Good review with diary observations of planting, in some places in NY State three times and getting frosted out.

One historian called it the the last subsistence crisis in the “Western World.”

Tambora is at 8 degrees south, trade winds need to be considered.

However Mayon (Philippines) is in the North Hemisphere at 13N, erupted on 1st February 1814 and appears to be clearly identified in the N. Hemisphere’s records.

Volcanic sulfur dioxide (SO2) from mount Etna is often found at altitudes of 7-8km.

In the Equatorial regions there is little of two hemispheres’ atmospheric mixing at such altitudes.

https://earth.nullschool.net/#current/wind/isobaric/500hPa/orthographic=102.02,-0.47,543

Altitude 5.5 km or 18,000 ft

Willis,

I’m curious as to whether there was a greater affect on Tmax or Tmin after Tambora? To my untrained eye there seems to be a noticeable low in the 1815 – 17 period. This isn’t obvious until you put the marker on the last chart.

Ben, I suspect that the main effect of volcanic eruptions is not a cold spike, but a lack of hot spikes …

w.

Thank you Willis, it is visible in the two yesrs after 1815 compared with the rest of the chart.

Willis,

“the effect on temperature was indistinguishable from natural fluctuations in other parts of the record.”

Stretch your x axis out more horizontally and it becomes less a part of the clutter. When one considers all of the potential causal variables acting upon temperatures it seems quite apparent that there is a significant impact by volcanic eruption aside from, or more to the point, in addition to all of the “natural” variation, of which this is simply one more natural occurrence.

Willis,

Your 2012 post on this subject is more enlightening regarding effects of volcanism. My opinion.

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2012/03/16/volcanic-disruptions/

There is not just one kind of volcano eruption. Each is unique, some with fine dust, some with coarse dust, some with almost none. Sulfur emissions vary. I suspect the difference in the records are due to such differences in volcanos.

DHR

There are also differences in the color and albedo of the ash. Violent eruptions from stratovolcanoes, which are most likely to reach into the stratosphere, will probably have ash with a higher albedo than ash from more mafic volcanoes. So, it is difficult to ascribe a quantitative behavior to ash injected into the stratosphere unless one at least knows something about the silica content of the ash. As a general rule of thumb, as dark ferromagnesian minerals are comminuted they become lighter in color, while opaque mineral stay dark or become darker. Sialic minerals tend not to change much. What is called the “streak” of a mineral is a good guideline to how the color might change. But, the point is, not all ash is the same. Climatologists who talk vaguely about ash being injected into the stratosphere are betraying their ignorance. At the level of real science, it is the particle size and the complex refractive index of the particles that are the most important consideration, and the information on the complex refractive index of various aerosols is available in the literature, although it is not comprehensive.

DHR, I agree. I read somewhere that a volcanic eruptions that ejects large amounts of sulphur into the stratosphere cause cooling. Those that don’t, don’t.

Actually, they cause warming in the stratosphere initially. Once the aerosols settle out ( a couple of years ) there is a net cooling of the stratosphere which is persistent. I have no idea whether this also happened back in 1815. Maybe recent conditions are different from then ( aircraft pollution , for example ).

This cooling implies that the stratosphere is more transparent after such an event and more solar energy gets through into the lower climate system. The probable net result is : global warming , not the cooling built into climate models.

See a fuller discussion here:

https://climategrog.wordpress.com/uah_tls_365d/

Thomas Jefferson kept exttensive weather records. He recorded 1816 as the year without a sumer.

Well, it was during the LIA. There were probably several years without summers during that few hundred years. Some of them even show up on Willis’ charts.

1816: the sumer without an m. 😉