From PRINCETON UNIVERSITY and the “it can’t be cyclic natural variation” department

How global warming is drying up the North American monsoon

New insights into the droughts and wildfires of the southwestern US and northwestern Mexico

Researchers have struggled to accurately model the changes to the abundant summer rains that sweep across the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico, known to scientists as the “North American monsoon.”

In a report published Oct. 9 in the journal Nature Climate Change, a team of Princeton and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) researchers have applied a key factor in improving climate models – correcting for sea surface temperatures – to the monsoon.

The report’s authors include Salvatore Pascale, an associate research scholar in atmospheric and oceanic sciences (AOS); Tom Delworth, a lecturer in geosciences and AOS and research scientist at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL); Sarah Kapnick, a 2004 Princeton alumna and former AOS postdoc who is currently a research physical scientist at GFDL; AOS associate research scholar Hiroyuki Murakami; and Gabriel Vecchi, a professor of geosciences and the Princeton Environmental Institute.

When they corrected for persistent sea surface temperature (SST) biases and used higher-resolution data for the regional geography, the researchers created a model that accurately reflects current rainfall conditions and suggests that future changes could have significant consequences for regional water resources and hazards.

“This study represents fundamental science relating to the physics of the North American monsoon, but feeds back onto weather to climate predictions and building resiliency for our water supply and responses to hazards,” said Kapnick. “I am excited about this leap forward to improve our models and for the potential applications that they will provide in the future to society.”

Their results highlight the possibility of a strong precipitation reduction in the northern edge of the monsoon in response to warming, with consequences for regional water resources, agriculture and ecosystems.

“Monsoon rains are critical for the southwest U.S. and northwest Mexico, yet the fate of the North American monsoon is quite uncertain,” said Pascale, the lead author on the paper. “The future of the monsoon will have direct impacts on agriculture, on livelihoods.”

Previous general circulation models have suggested that the monsoons were simply shifting later, with decreased rains through July but increased precipitation in September and October.

“The consensus had been that global warming was delaying the monsoon … which is also what we found with the simulation if you didn’t correct the SST biases,” Pascale said. “Uncontrolled, the SST biases can considerably change the response. They can trick us, introducing artefacts that are not real.”

Once those biases were corrected for, the researchers discovered that the monsoon is not simply delayed, but that the total precipitation is facing a dramatic reduction.

That has significant implications for regional policymakers, explained Kapnick. “Water infrastructure projects take years to a decade to plan and build and can last decades. They require knowledge of future climate … to ensure water supply in dry years. We had known previously that other broadly used global models didn’t have a proper North American monsoon. This study addresses this need and highlights what we need to do to improve models for the North American monsoon and understanding water in the southwest.”

The new model also suggests that the region’s famous thunderstorms may become less common, as the decreased rain is associated with increased stability in the lower-to-middle troposphere and weakened atmospheric convection.

“The North American monsoon is also related to extreme precipitation events that can cause flash floods and loss of life,” Kapnick said. “Knowing when the monsoon will start and predicting when major events will happen can be used for early warnings and planning to avoid loss of life and property damage. This paper represents the first major step towards building better systems for predicting the monsoon rains.”

The researchers chose to tackle the region in part because previous, coarser-resolution models had shown that this area would be drying out, a prediction that has been borne out in the droughts and wildfires of recent years. But most of those droughts are attributed to the change in winter storms, said Pascale.

“The storm track is projected to shift northward, so these regions might get less rain in winter, but it was very uncertain what happens to the monsoon, which is the other contributor to the rains of the region. We didn’t know, and it’s crucial to know,” he said.

In their model, the researchers were able to tease out the impacts of one factor at a time, which allowed them to investigate and quantify the monsoon response to the doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide, increased temperatures and other individual changes.

Pascale stressed the limits of this or any other climate model. “They need to be used with an understanding of their shortcomings and utilized to their expected potential but no further. They can give us quite reliable information about the large scale atmospheric circulation, but if you want to look at the regional, small-scale effects, you have to be very careful,” he said. “Models are critical but they are not perfect, and small imperfections can lead to big misunderstandings.”

He continued: “We are not saying, ‘We are sure that this is what will be,’ but we wanted to point out some mechanisms which are key, and have to be taken into account in future research on the North American monsoon. This is a difficult region, so future research will point out if we were right, and to what extent.”

###

The research was made possible by enhancements to NOAA’s research supercomputing capability including access to Gaea and Theia and by the NOAA CICS grant NA14OAR4320106.

Manuscript: Pascale, S., Boos, W. R., Bordoni, S., Delworth, T. L., Kapnick, S. B., Murakami, H., Vecchi, G. A., Zhang W. (2017): Weakening of the North American monsoon with global warming, Nature Climate Change, in press. Doi:10.1038/nclimate3412

***this 10pm quote is all over the MSM. any ideas why this would be?

9 Oct: Sacramento Bee: Homes and businesses burn as fire rips through Santa Rosa. One confirmed dead in Mendocino

By Ryan Lillis, Molly Sullivan, Tony Bizjak and Benjy Egel

Gov. Jerry Brown has declared a state of emergency in Napa, Sonoma and Yuba counties, where wind-whipped fires have destroyed at least 1,500 structures, including many homes and businesses in Santa Rosa, and forced more than 20,000 people to evacuate their neighborhoods…

***Most of the fires started at about 10 p.m. Sunday and their causes are under investigation, officials said…

http://www.sacbee.com/news/state/california/fires/article177823806.html

saw a comment on one website, saying –

Some of these fires are separated by over 100 miles, yet they started about the same time.

No clouds. No lightening. Just winds sustained at 30-40mph with gusts to 70. Relative humidity was hovering below 20%…

Sounds like co-ordinate arson to me.

“Researchers have struggled to accurately model …””

The only interesting thing they had to say. Their models are worthless junk. End of story. Cut off their funding.

Improved models by correcting sea surface temperatures – hmm, so Karlization of SSTs made the models work better, doing double duty killing the “Pause” (which will be back this winter.) The quality of papers on Climate Change these days seem to have a pleading character, as if they know nobody is paying attention anymore.

The puniness of the issues they raise: Gee western Mexico is no longer a Garden of Eden, they got all these cactuses. Global warming caused margaritas. Where in hell did cactuses come from? Coconuts, I get.

In the snowball earth article PIK adjusted geologic time by 400million years to rearrange the coal ages (Carboniferous) to jibe with snowball earth. I think they used BEST methodology to homogenized it and pasteurized it but don’t quote me on it.

As always ….. let’s wait 20 years and see just how reliable these new adjustments are. Someone, please bookmark, scan the artical and any graphs for future comparisons …… and of course, future blink graphs showing now and then.

It is quite easy to model the past. With enough variables, there will always be SOMETHING that correlates. An example is sports teams and presidential elections. There will always be some league of some sort somewhere that correlates quite well with the winning presidential election party.

Though, as Yogi said: “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

I’m just going to drop this here. It’s an article about a “nonprofit” (meaning grant-money-swallowing) organization telling us how “climate change” is costing the US $240 billion a year in damages. Um, no – damage to personal is usually paid for by homeowners and national flood insurance, which costs the US nothing, so that’s a completely bogus claim.

The chart included with the article is bogus, also, because the third column (green) covers only the 2007-2017 period instead of the first 10 years of the 21st century. That’s not how you do those things. But let’s not quibble over the fact that it’s another ‘gimme-gimme-gimme’ for grant money. Let’s just have some fun with it, right?

Here’s the link. It’s from Accuweather.

https://www.accuweather.com/en/weather-news/study-human-induced-climate-change-costs-us-economy-240b-per-year/70002906

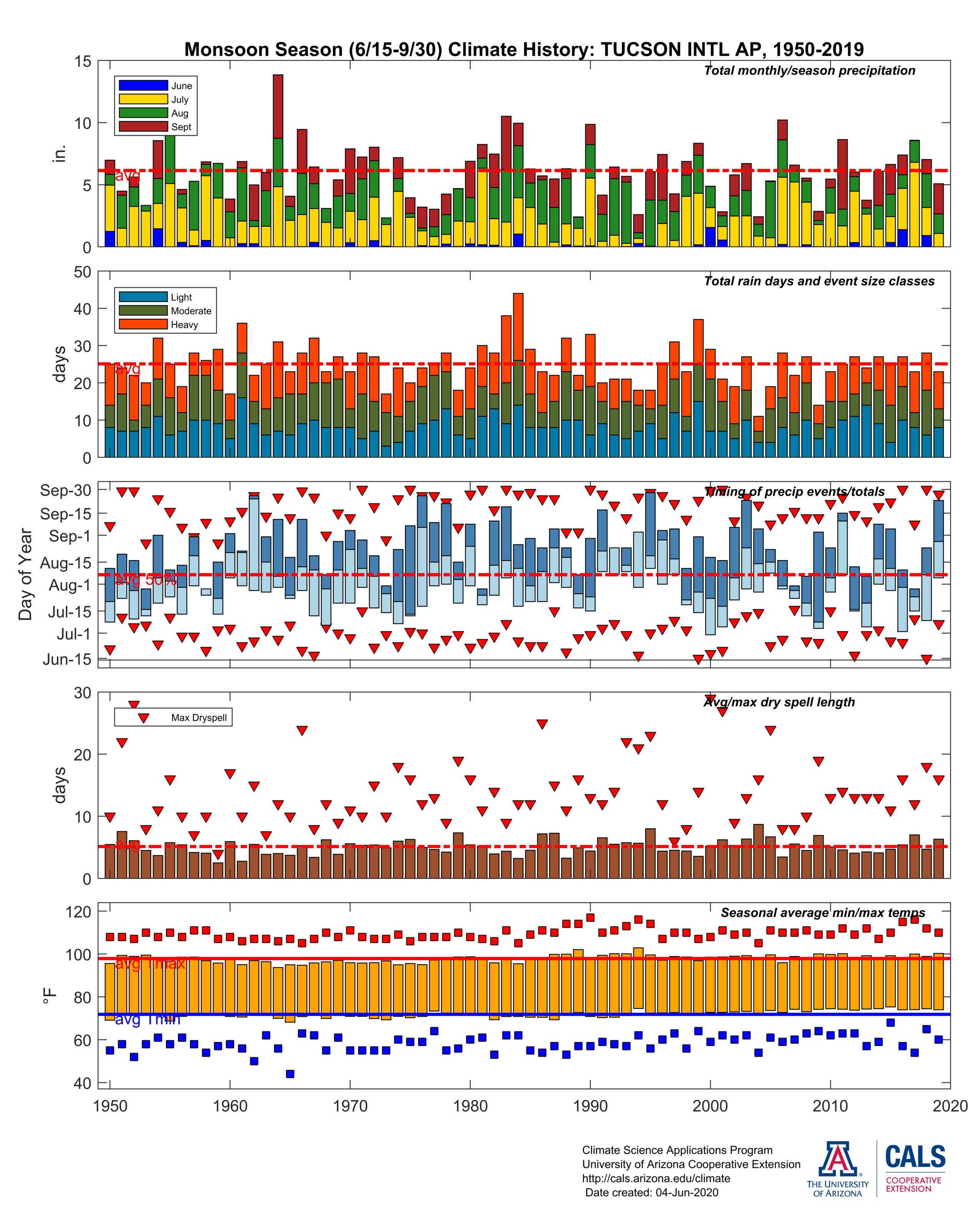

The local Tucson U of A data over the last 67 years at Tucson International Airport doesn’t seem to show much of a trend either way –

Perhaps their data needs adjustment to suit the model?

I just want one question answered “what caused all the climate change through out earth’s history?” We had climate change before man I quess Dino farts ruined the enviroment.

SST biases. How much in grant money is that worth?

The water pools that generate the vast amounts of water vapor are mobile, they move with the ocean cycles. It appears as they move back and forth across the equator, and they are currently north of the equator, and when they return to the south, the latitude where the atm rivers point will move south along with the warm pools.

This is all that’s happening. Because air responds differently over land, and land is not symmetrical, global average temperatures vary with the cycles.

In the American Southwest, there are two rainy seasons: the summer monsoon when the storm patterns are tropical—high humidity that builds up into thunderheads and rain; and the winter rains pushed by continental weather fronts, like the summer rains in the Midwest. Between those two weather patterns there’s a dry buffer zone of dryness where it doesn’t rain.

In southern Arizona one can see the changes over the seasons: winter rains, then in the spring dry, dry, dry with no rains, summer from mid June to end of September summer monsoon, fall again dry, dry, dry with no rain, as the pattern moves north and south with the seasons.

Unfortunately, winter is too cool for growing crops, so an increase of winter rains won’t help agriculture.

Knowing this pattern, what should we expect with global warming? With global cooling? Will the pattern move north or south with global warming? With global cooling?

This past year in Tucson, Arizona, the winter rains lasted longer than normal, then came dryness so bad that even some cacti died, the summer monsoon came late but ended two months early, and now there’s the fall dryness. Is this the pattern expected with global warming, or global cooling?

I’ve looked at the various station in the US SW.

This is the averages of the day to day min and max temp change by year.

This is also about regional weather variability. Not global climate change, in which the USA is a small and self obsessed part. Just pointing out the science fact. Statistically relevant climate change occurs over several insignificant human lifetimes.