Guest Post By Willis Eschenbach

Often I start off by looking at one thing, and I wind up getting side-tractored merrily down some indistinct overgrown jungle path. I was thinking about the difference in the strength of the sunshine between the apogee aphelion, which is when the Earth is furthest from the sun in July, and the perigee perihelion in January, when the Earth and the sun are nearest. On a global 24/7 average value, there is a peak-to-peak aphelion to perihelion swing of about twenty-two watts per square metre (22 W/m2). I note in passing that this is the same change in downwelling radiation that we’d theoretically get if starting in July the CO2 concentration went from its current level of 400 ppmv up to the dizzying heights of 24,700 ppmv by January, and then went back down again to 400 ppmv by the following July … but I digress.

Now, because the Earth and sun are nearest in January when the southern hemisphere is tilted towards the sun, there is a larger swing in the solar strength in the southern hemisphere than in the northern.

While I was investigating this, I got to looking at the corresponding swings of the ocean surface temperature. I split them up by hemisphere, and I noticed a most curious thing. Here’s the graph of the annual cycle of solar input and sea surface temperature for the two hemispheres:

Figure 1. Scatterplot, top-of-atmosphere (TOA) solar input anomaly versus ocean surface temperature. Northern hemisphere shown in violet, southern hemisphere shown in blue. Monthly data has been splined with a cubic spline. Data from the CERES satellite dataset.

So … what is the oddity? The oddity is that although the swings in incoming solar energy are significantly larger in the southern hemisphere, the swings in ocean temperature are larger in the northern hemisphere. Why should that be?

The difference is impressive. As a raw measure, the northern hemisphere ocean surface temperature changes about seven degrees C from peak to peak, and the TOA solar varies by 216 W/m2 peak to peak. This gives a change of 0.032°C per W/m2 change in solar input.

In the southern hemisphere, on the other hand, the ocean surface temperature only swings 4.7°C, while the solar input varies by 287 W/m2 peak to peak. This gives a change of .0162°C per W/m2, about half the change of the northern hemisphere.

So that’s today’s puzzle—why should the ocean in the northern hemisphere warm twice as much as the southern hemisphere ocean for a given change in solar forcing?

Part of the answer may lie in the depth of the ocean’s mixed layer. This is the layer at the top of the ocean that is mixed regularly by a combination of wind, waves, currents, tides, and nocturnal overturning. As a result, in any given location the mixed layer all has about the same annual average temperature. (However, monthly changes are still largest and the surface and decrease with increasing depth.) This mixed layer worldwide averages about 60 metres in depth. But the mixed layer is deeper in the southern hemisphere, averaging about 68 metres in the southern hemisphere versus about 47 metres in the northern.

However, two things argue against that conclusion. One is that the mixed layer in the southern hemisphere is about 45% deeper than in the northern … but the northern hemisphere sensitivity of temperature to incoming solar is double, not 40% larger.

The other thing that argues against the mixed layer difference is that the thermal lags in the two hemispheres are very similar, with peak temperatures in each hemisphere occurring almost exactly two months after peak solar. In a previous post entitled “Lags and Leads” I discussed how we can use the difference in time between the peaks of solar power and temperature shown in the scatterplot in Figure 1 to calculate the time constant “tau” of the system. This two month lag is equivalent to a time constant tau in both hemispheres of 3.3 months.

Then, using that time constant tau we can calculate the equivalent depth of seawater needed to create a thermal lag of that duration. A time constant tau of 3.3 months works out to be equivalent to 25 metres of seawater with all parts equally and fully involved in the monthly temperature changes (or a deeper mixed layer with monthly temperature swings decreasing with depth).

But since the time constant “tau” is the same for both hemispheres, this means that the equivalent depth of water that is actually involved in the annual cycle is the same in both hemispheres.

Or in other words, the more of the ocean that is involved in monthly temperature swings, the greater the lag there will be between solar and temperature peaks. But in this case, the thermal lags are the same in both hemispheres, meaning the equivalent depth of ocean involved is the same.

Then, I thought “Well, maybe it’s because one pole is underwater and the other pole is on land”. So I repeated the calculation of the temperature and solar swings using just the range from 60° North to 60° South, in order to eliminate the effect of the poles and the ice … no difference. The northern hemisphere non-polar ocean warms twice as much for a given change in solar energy as does the southern non-polar ocean. The difference is not at the poles.

So my question remains … why is the northern hemisphere ocean surface temperature twice as sensitive to a change in solar input as is the southern hemisphere ocean temperature?

My best to all. Here, we have had a rare June rain, most welcome in this dry land, so for all of you today, I wish you the weather of your choosing in the fields of your dreams …

w.

My Usual Request: Misunderstandings can be minimized by specificity. If you disagree with me or anyone, please quote the exact words you disagree with, so we can all understand the exact nature of your objections. I can defend my own words. I cannot defend someone else’s interpretation of some unidentified words of mine.

My Other Request: If you believe that e.g. I’m using the wrong method or the wrong dataset, please educate me and others by demonstrating the proper use of the right method or the right dataset. Simply claiming I’m wrong about methods or data doesn’t advance the discussion unless you can point us to the right way to do it.

UPDATE: Here are two maps of the same data, which is the change in ocean temperature per 0ne watt/metre squared (W/m2) change in top of atmosphere (TOA) solar radiation …

The gray contour lines show the global average value of 0.02 °C per W/m2.

There are five more days included in the vernal equinox to the autumnal equinox time span as compared to the autumnal equinox – vernal equinox time span. Maybe this accounts for something.

Good point! Would it make a difference if it were 50 days?

Also, if the increased intensity of the sun in the Southern Hemisphere causes earlier thunderstorms than the lessened solar intensity in the Northern Hemisphere (something that was noted by Willis several months ago) then the added five days of sunlight coupled with the lessened cooling effect of thunderstorms could possibly have a noticeable accumulative effect.

Maybe; Just throwing this out as something to look at.

If the amount of time and the amount of intensity that went into heating up a body of water made no difference then the body of water would heat up to same temperature no matter what the time or the intensity as long as the total energy that went into the body of water remained the same.

But when the intensity causes such energy releasing phenomena such as thunderstorms to occur then the degree of intensity and the time of this intensity would make a difference.

Lessened solar intensity and lengthened time should decrease the energy lost due to thunderstorms in the Northern Hemisphere as compared to the decreased amount of time and increased solar intensity in the Southern Hemisphere.

Marv said:

Right you are, Marv, …… but the fact is, …… the question involves two (2) different bodies of water, to wit:

Willis Eschenbach said:

Well now, the logical answer to the above question is:

It requires less thermal energy, or Solar energy in this case, to warm-up the water in a small pot (NH) than it does to warm-up the water in a larger pot (SH).

Or, to be more specific to the questioned asked:

If the same intensity of Solar energy is applied for the same amount of time ……. to both a small pot (NH) and a larger pot (SH) of water, …… the water in the smaller pot (NH) will attain a higher temperature than the water in the larger pot (SH).

And the following graphic defines the relative sizes of the two (2) pots (hemispheres) in question:

http://theworldsoceans.com/oceans.jpg

Okay, I’m going to give it another try to get my point across:

If thunderstorms are formed as a result of the intensity of sunlight hitting the ocean’s surface and these thunderstorms act to transfer heat from the ocean’s surface to several miles upward AND if the clouds from these thunderstorms act to block sunlight from hitting the ocean’s surface then it follows that the more thunderstorms that are formed over the ocean the less will be the resultant heating up of the ocean’s waters.

If the intensity of the sunlight increases then the number of thunderstorms, the intensity of the thunderstorms AND (and possibly the most importantly) the timing of the thunderstorms will be altered, meaning the thunderstorms will begin to form early in the day. Plus the increased intensity will cause the ‘swath’ – the width – of the thunderstorm band to be increased over the ocean’s surface. Add to this the diminished amount of sunlight days in the Southern Hemisphere as compared to the Northern Hemisphere and you will end up with a significant edge in Northern Hemisphere ocean warming as compared to Southern Hemisphere warming.

My guess is that the relative percentages of land in the NH vs SH might be important.

With more land in NH, there is less water (?) for the sun hitting the water to warm (or to let cool). However, all that extra land still gets heated, and as rain falls on the land it gets heated (or not in winter). As the rain gets drained into the oceans, the extra heat affects the ocean max & min temperatures.

Part of the extra delay in the NH may be due to the snow which doesn’t flow down to the sea until it melts first.

Samuel C Cogar,

That would be true iff the same amount of energy were involved. Unfortunately it isn’t. He was writing about a number of watts per square meter being the same, which is fine except it is integrated over the surface area, meaning that the northern hemisphere receives less energy than the south, but heats far more.

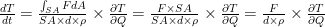

The reasoning for the above goes something like this:

Which (if the latex shows up) leads to a surface area term in the numerator and denominator making total energy unimportant.

The better analogy on your pots is two pots of the same heights but differing surface area each sitting on a burner that puts out the same amount of energy per unit area. The two pots will heat at exactly the same rate. Of course that is part of the conundrum here, since the data says they obviously do not heat at the same rate. This begs the question of is there more cloudiness in the southern hemisphere? It would not take much difference in cloud surface area to throw the equivalences off.

In short I don’t have the answer either, but I don’t think it has to do with the surface area. Perhaps it has to do with the effects of the northern hemisphere currents pumping the same volume of water pole-ward where it is mixed with a much smaller volume of northern hemisphere surface water? We can’t let ourselves fall into the same trap as the climate crowd and blame everything on radiation and forget about convection and conduction. The ocean is a pretty complex environment.

@ur momisugly Owen in GA

Now that was a fine response ……… so maybe you can answer another question for me.

Let’s say that you were really, really hungry …. and needed something to eat pretty quickly ….. and decided to fix yourself a single-serving of noodles, ……. would you put a five (5) gallon container of water on your stove burner to bring to a “boil” (212 F) before you put the noodles in for cooking …… or ……. would you put a one (1) quart container of water on your stove burner to bring to a “boil” (212 F) before you put the noodles in for cooking?

Owen in GA, which one (1) of those two (2) pots of “noodle-cooking-water” will begin to “boil” (212 F) in the least amount of time?

And please explain your answer to edumacate me on this subject.

And ps, Owen in GA, iffen you have ever been in the North country (New York/Minnesota) in the Springtime you would surely notice that a small lake receives the …… “same number of watts of Solar irradiance per square meter of surface area” …… as does a large lake ……. but, due to the H2O temperature difference, one can go “skinnydipping” in the small lake a couple of weeks earlier than they can in the larger lake.

Small swimming pools, farm ponds and lakes “warm-up” the quickest come Springtime.

And the inflow of river water, the THC and the Gulf Stream helps the Atlantic Ocean “warm-up” come Springtime.

[Note that “shallow water” vs. “deep water” is more important than “large lake” or “small” lake. .mod]

Samuel C Cogar,

) SA is surface area, d is depth,

) SA is surface area, d is depth,  is density and Q is heat energy.

is density and Q is heat energy. gets wonky.

gets wonky.

Lived for a big part of my growing in those northern parts (though somewhat south of your examples – in Illinois). The farm pond was usually about 6 or 7 feet deep while the lake down the way was nearly impossible to find the bottom when diving. (I was 8 or 9 when I tried to find the bottom so it was probably only 20 or 30 feet deep. One of the ponds was spring fed so it tended to stay unfrozen except for the worst part of January or February. I would not have liked to swim in it from October on to May – never got the fascination with those “polar bear clubs”.) The lake is a much larger mass of water to heat up in the water column. In my experience, melting on most of the ponds was more a function of air temperature and rainfall than sunlight. In the example of the two pots we have a fat pot that is very deep versus a small pot that is very shallow.

As to the pot configuration for some quick noodles – provided the burners were able to provide heat across the bottom of each, I would put 3 or 4 inches of water in the bottom of the 5 gallon pot rather than fill up the quart pot. They would each have a quart or two of water, but because of the much larger surface area contacting the burner, the larger pot would boil much more rapidly. I would be eating noodles while the quart pot was coming to a boil. Thermal physics is a really fun course when noodles are at the end…

The fun thing in thermal physics is that the rate at which something heats up is proportional to the amount of heat and inversely proportional to the mass of stuff being heated. This also applies to the rate at which it gives up heat (i.e. cools).

F is flux (

A simplification about mixing the heat assuming that all the water stays at the same temperature in the water column is implied in the above. Also I have made a simplifying assumption that the flux is constant when clearly it is not constant in the case of a pond/lake/ocean but is for the pots on the stove.

Another fun thing in thermal physics is the “constant” of proportionality isn’t constant but is explicitly dependent on the current temperature of the media in sometimes unexpected ways, but is a property of the stuff in question. (It is possible to figure it out from first principles using the atomic and crystalline geometries and bond strengths, but the math gets insane, and knowledge of all the bond phase changes has to be known for inflection point boundary conditions.)

The equations aren’t useful when 40F water falls onto the surface of the frozen pond because it messes the flux number up. Also, state changes are one of the places where the “constant” of proportionality

@ur momisugly Owen in GA

The “burners ”, ….. what burners ya talking about?

There is only one (1) Stove burner for separately heating the 2 metallic pots of water …. Just like there is only one (1) Solar burner for separately heating the 2 hemispheric pots of water.

Here are the “figures” as stated by Willis E., .. which you either have to find fault with ….. or use as-is in your calculations, to wit:

Pot #1 – northern hemisphere ocean water:

1. ocean surface temperature changes about 7°C from peak to peak,

2. TOA solar varies by 216 W/m2 peak to peak.

3. 0.032°C per W/m2 change in solar input.

Pot #2 – southern hemisphere ocean water:

1. ocean surface temperature changes about 4.7°C from peak to peak

2. TOA solar varies by 287 W/m2 peak to peak.

3. 0.0162°C per W/m2 change in solar input

And to wit summation:

A. TOA solar varies by 216 W/m2 …. verses …. 287 W/m2

B. Surface solar input varies by 0.032°C per W/m2 …. verses ….0.0162°C per W/m2

So, looks to me like, given the above A./B. figures, there is less steady Solar irradiance at the TOA of the Southern Hemisphere ….. which would explain why there is less variation in its solar input at the surface.

Right, ….. or am I wrong on that?

Remember, the warming of the ocean water is not determined by “peak periods” of solar irradiance ….. but by the cumulative solar irradiance for a given time period.

Hi Sam

perhaps I should give you some of my results to consider (past 40 years)

maxima went up by 0.036 K/annum globally

0.028K/annum NH

0.043K/annum SH

minima went up by 0.006 K/annum globally

0.025K/annum NH

-0.013K/annum SH

obviously these are my results, which is a summary of 27 stations SH and 27 stations NH.

It more than accounts for temp swings. When we start getting summer at perihelion, the extra week or so of warming becomes a week or so of cooling, and ice ages start. Very hot, but very short summers.

And it is more than 5 days. It is nearly 2 weeks.Count the days from spring equinox to vernal.

Summer is getting longer, spring is getting shorter. Total warming season length (summer/spring) is 186.4 days, vs 178.8 cooling days, or nearly 12 days.

And it should be:

It more than accounts for temp swings. When we start getting summer at perihelion, the extra week or so of warming becomes a week or so of cooling, and ice ages start. Very hot, but very short summers.

And it is more than 5 days. It is nearly 2 weeks.Count the days from spring equinox to autumnal.

Summer is getting longer, spring is getting shorter. Total warming season length (summer/spring) is 186.4 days, vs 178.8 cooling days, or nearly 12 days.

Next years warming season length is 186.2 days.

(2017-09-22 16:21) – (2017-03-20 11:29) = 186.2 days

And my math is suffering today. Difference is about 7 days, not 12….sigh….

Cool.

I would think the land masses in the NH cause ocean current interplay differently than in the SH.

Agree. And the difference would be in resulting air temperatures over NH land masses, which reflect rather than absorb IR (unlike SH ocean). The result is convective energy transfer in the NH between warmed land and ocean.

IR does not penetrate oceans, but UV can to several meters. The differences in ocean behaviour might be rooted in the ozone depletion physics via the differences in NH vs SH polar vortexes. SH is oftem more conatined and the Summer/ winter cycle is much stronger. Hence larger ocean response to UV. Check out nullschoolearth and macc.aeronomie.be sites for atmopheric data.

I’ll do exactly that, and thank you for the enhanced hypothesis.

As an example of this, check out the equatorial current in the Atlantic, both above and below the Equator.. It reaches the part of South America which is angled to the NorthWest, including the entire flow of the Amazon, and the current continues northwest into the Caribbean.

At the mouth of the Amazon, rain which fell in the Southern Hemisphere exits into Atlantic right at the Equator, and joins the Current to the Northwest.

These two features shuffle energy from Southern Hemisphere insolation into the Northern Hemisphere.

Animation a t earth.null school

https://earth.nullschool.net/#current/ocean/surface/currents/orthographic=-40.41,13.36,864

Land areas are distributed predominantly in the Northern Hemisphere (68%) relative to the Southern Hemisphere (32%) as divided by the equator. Land is less affected (stays constant temperature about 5 feet down) than ocean, which means in north there is less ocean to absorb the radiation (that is bouncing around in that area).

So that leaves half the amount of sea surface area in the NH compared to the SH exposed to any warming influence. Half a kettle boils quicker than a full one.

Do ocean scientists compare the composition of seawater from northern and southern hemispheres?

Maybe there is another variation, more salts or “additives” in the water.

More cars in the NH driving around wearing their tyres out which unavoidably then gets washed into the sea.

Your half a kettle has the same heated area as it does full. As a result your point does not apply. Snow covered land areas in Northern winters get much colder than ocean surface air. In Summer, Northern land masses get warmer than air over the open ocean. Ocean air may have high enthalpy due to humidity.

I suspect this is at the root of Willis’ observations. I believe the differences between Northern an Southern hemispheres link strongly to long term ocean and atmospheric circulation patterns which we barely understand at this point.

John H said:

“Your half a kettle has the same heated area as it does full.”

Its the volume of water that really matters, ….. not the surface area.

Maybe someone can make another graph using the Land/Ocean hemispheres instead. To see if the four sensitivities rank, in descending order: LH, NH, SH, WH

But land(continents) are more easily heated and cooled than water, so perhaps there’s some atmospheric-to-ocean heat transfer that is stronger in the North than it is in the South? Precipitation perhaps. Prevailing thought is that Ocean circulation is what makes the N. Hemi. the warmer, and wetter one.

Willis’s observations are regarding ocean water temps. In Winter the air blowing from land to water is cold and dry, causing the ocean to give up more heat. In Summer that air is warm and less dry and only picks up humidity as the ocean warms.

Another try! Snow covered land (more in the North), cools the NH in Winter. The same land (still more in the North), has lower albedo and warms the NH in Summer. The SH, being mostly water, is more stable in temperature. I would expect air temperatures show a similar dichotomy ( couldn’t think of a better word, lol). Obviously, although the SH oceans show less Summer warming, they are putting a tremendous amount of moisture into the air. In the NH the Summer heat input shows up more as higher air temps.

Could there be a difference in cloud cover/albedo caused by greater amounts of evaporation in the hot ocean summer in the south vs the warm land mass summer in the north?

Less ocean surface area in the North.

NOAA says the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans are very evenly divided between the hemispheres, but the Indian Ocean looks to me to be about 90% in the SH. That works out to be roughly 60% of the total in the SH but only 40% in the NH, which would mean 50% more water in the SH than in the NH. So if we considered the entire ocean temperature to be involved in the response to solar radiation there would be a greater response in the NH. I realize you are only talking about the ocean surface temperature, but over very long periods of time one would expect a smaller body of water to show a stronger response to solar radiation. Too bad we can’t get a very good idea of average temperature for the entire ocean.

https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/global/etopo1_ocean_volumes.html

Lance,

That NOAA link says that the VOLUMES are equal. However, the surface areas are not and the surface is where heating and cooling takes place. With more land area in the NH, there will be a greater range of heating and cooling over the land (because water has a greater thermal mass), influencing ocean surface temperatures when the winds blow over the ocean. That is, cold air in the Winter will cool the surface of the oceans, and hot air will warm the surface of the oceans in the Summer.

My thoughts also, but you said it more clearly.

Perhaps a different color spectrum due to different plankton distributions, or cloud patterns over the SH may be quite different in response to seasons as in the land-heavy NH. Sediment distribution differences may also affect the color spectrum.

Got to ponder this. The data is persuasive. Agree delta mixed layer is not an answer. Tau arguement is a clincher. So, we have another mystery like Peter Webster’s symmetry between hemispheric albedos. Here, asymmetry between SST and seasonal insolation. And Websters observation rules out delta hemispheric albedo as an alternative explanation.

Maybe to do with more rain falling on land in the northern hemisphere and being warmed before it flows back into the sea?????

…less land, more water

more land, less water

surface

Sensitivity as a function of latitude?

May be that is the right explanation: the NH starts with relative more ocean near the equator, reducing polewards, in the SH it is opposite.

Insolation has its highest influence near the equator, thus for the NH has relative more influence of insolation changes than the SH.

Some work to do for Willis by partitioning the relative insolation over several latitude bands?

Ferd:

I think you nailed, plus unless I am mistaken there is a larger amount of warm water circulation that heads north from the equator to be radiated out in the land free North Pole region then occurs southward because of the land locked nature of the South Pole.

Ferd:

I think you nailed, plus unless I am mistaken there is a larger amount of warm water circulation that heads north from the equator to be radiated out in the land free North Pole region then occurs southward because of the land locked nature of the South Pole. Vv

Bob Boder,

That is the case in the Atlantic: the THC – Gulf stream brings warm water from below the equator to the NE Atlantic sink places, thus may be warming faster with increased insolation over the mid-latitudes…

Not sure how that performs in the Pacific…

One can often figure out things of this nature by thinking of extreme examples. In this case, there is more water in the south, and there is also more solar difference in the south. However the north shows more variability.

So let us use an analogy. We have a 10 kilogram lead ball and a 1 kilogram lead ball. We have two water baths for the 10 kilogram lead ball at temperatures of 10 C and 90 C.

For the 1 kilogram ball, we also have two water baths, but at 20 C and 80 C.

Now we place each ball in their cold water bath for 2 minutes and then place them into their warm bath for 2 minutes and repeat. Which lead ball would have the greater difference in temperature?

I would say the 1 kilogram ball with baths of 20 C and 80 C would have a greater difference than the 10 kilogram ball with baths of 10 C and 90 C.

Lance Wallace June 18, 2016 at 1:31 pm

… but the Indian Ocean looks to me to be about 90% in the SH. That works out to be roughly 60% of the total in the SH but only 40% in the NH, which would mean 50% more water in the SH than in the NH. So if we considered the entire ocean temperature to be involved in the response to solar radiation there would be a greater response in the NH…

———————————————-

Just thinking to my self, I need a map.

Boom there it was in the link you posted, hey thank you..

“”So my question remains … why is the northern hemisphere ocean surface temperature twice as sensitive to a change in solar input as is the southern hemisphere ocean temperature?”””

Water and ice. Mass in the southern hemisphere is greater, we know this because of the wobble in Earth’s rotation.

Slower rotation more wobble, in the N. Hemisphere, creating different mixing regimes between the two hemispheres.

Faster rotation, well quicker wobble? lol but would affect mixing regimes.

More herky, jerky mixing patterns in the northern hemisphere.

I think that it is already expressed in tectonic boundaries, undersea volcanic ridges etc., for the N. hemisphere, too..

I suspect there is more upwelling of cold bottom water getting into SH currents.

@ur momisugly Richard M, 5:10 pm June 18th, I was thinking the same thing. To me the continuous circulation of the Southern Ocean circulating around Antarctica ( the Westerlies) must have an effect year round. ( from the article: ” the southern hemisphere, on the other hand, the ocean surface temperature only swings 4.7°C, while the solar input varies by 287 W/m2 peak to peak. This gives a change of .0162°C per W/m2, about half the change of the northern hemisphere.”

If opening of the Drake passage and newly formed the ACC did cause global cooling (not just Antarctica) you would have to put your money on ocean currents being the difference. But it can’t be simply mixing with colder water, the cooling needs to be loss of energy to space (so what mechanism is in the models for how ocean currents affect the cooling of the Earth?)

Not long enough data to see correlation with max/min ice extent in the Antarctic for eg?

I had the same thought as Richard M. My understanding of the THC is that whereas NH surface movement is pretty much one-way (S-N) with the surface water sinking in the N latitudes and returning S via the deep ocean, SH surface movement is two-way with some THC cold water upwelling in the S ocean then moving N (Humboldt Current, eg.). Not sure exactly what or how much difference it would make, but maybe all N warming stays in the N, whereas some S warming leaves the S and adds to the N?

Yup, that helps. If we imagine the line of the equator oscillating back and forth seasonally from Tropic to Tropic, with the colour scheme moving in concert, we get a great image of the earth as a pumping heat engine. All that heat input at the tropics creating wind, ocean currents and clouds; and losing heat to space faster and faster as the heat carriers move toward the poles. More heat in, and I don’t think CO2 related warming is anything but a very weak theory, you just get a little faster heat engine.

AGW theory would have some value if it’s adherents actually took an interest in understanding earth’s weather and climate. Instead they just stumble endlessly over the same ground, determined to see what isn’t there.

“Just thinking to my self, I need a map.

Boom there it was in the link you posted, hey thank you..”

But it’s a highly distorted map ( only approx accurate at equator !!! ), to get a better understanding of the actual areas of land, water & ice look at a globe.

Try this interactive one https://earth.nullschool.net/#current/ocean/primary/waves/overlay=significant_wave_height/orthographic=74.33,2.59,277

• Use mouse button to rotate

• Click on ‘earth’ to change parameters

More info https://earth.nullschool.net/about.html …..lots to explore.

1saveenergy June 19, 2016 at 1:37 am

—————————————————-

Thanks, for the link, haven’t visited the wind map since the breakup of the N. hemisphere vortex this earlier this spring. Had to check the S. Polar vortex while there and found speeds up 213 mph. wow.

My bad, I said southern hemisphere mass. When meant water and ice greater.

Like Willis said, “”Often I start off by looking at one thing, and I wind up getting side-tractored merrily down some indistinct overgrown jungle path. “”

For me that’s an understatement and more like a way of life. sorta

From Earth’s wobble, back to the EEJ (equatorial electro jet), and its asymmetries between Northern and Southern hemisphere and the effect of variations in F10.7 flux.

First results from the Swarm Dedicated Ionospheric Field Inversion chain

A. Chulliat, P. Vigneron, G. Hulot

13 June 2016

Abstract

…”’They also reveal a peculiar seasonal variability of the Sq field in the Southern hemisphere and a longitudinal variability reminiscent of the EEJ wave-4 structure in the same hemisphere. These observations suggest that the Sq and EEJ currents might be electrically coupled, but only for some seasons and longitudes and more so in the Southern hemisphere than in the Northern hemisphere….”’

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s40623-016-0481-6#Sec7

Not to mention that the Earth’s magnetic equator is mostly above the physical equator.

So,

“Better run through the jungle

Whoa, don’t look back”

https://youtu.be/EbI0cMyyw_M

How do you define your ocean surface temperature anomaly? Did you weigh local temperature anomalies by area? Did you exclude areas near equator?

Bear in mind the two polar oceans: the Arctic at 14 M km2 vs. Southern Ocean around Antarctica is 22M km2.

The middle/high latitudes in the southern hemisphere is mostly ocean. Cloudiness and weather patterns change little over the year there (the climate is hypermaritime, with little difference between winter and summer).

In the north these latitudes are mostly land. Land areas cool and heat up much faster than ocean which means that weather patterns and cioudiness varies much more in the north, and the cloudiness in particular strongly affects heat absorption by the oceans.

Yes, my thought was cloudiness too. That is the obvious missing variable in Willis’ article.

The solar radiation figures are TOA. The temperatures are surface. There is one big thing missing from that picture : the atmosphere.

Willis says:

How almost exactly? As you have pointed out in ‘lags and leads’ article the response never gets more than 90deg out of phase. Once the phase lags is around 2 months increasing heat capacity will make progressively less difference to the lag. A near infinite heat sink would only produce another month of lag so how much difference would 40% more make in terms of time lag and how accurate is notion that they are about the same?

Obviously it’s not either/or. It could be a combination of mixed layer depth and differences in cloud response to the annual cycle.

PS.

Here in the south of France, the greyest May and June I can recall in the 20y I’ve been living here. Apart from a very mild start to the year, it does not look like the summer is going to be breaking any records. ( Until it gets corrected and homogenised, of course. ).

Ok, I remembered something, did two quick checks, and present here a testable hypothesis for the hemispheric difference. It is well known that the Gulf Stream varies significantly seasonally, with a ~3 month lag (hello, tau). It is much stronger summer fall than winter spring ( the lag). It is a major heat transport mechanism variably warming the North Atlantic. But the Atlantic is a lot smaller than the Pacific, so by itself could not explain Fig. 1.

Googled northern hemisphere pacific currents, Sure enough, there is one: NECC. Bigger, more diffuse than Gulf Stream. But does the same thing, the same way, in the same direction. Aha!

So, is it significantly seasonal?

Well, according to Wang et. al., J. Phys. Oceanography 32: 3474-3489 (2002) YES.

So my quickie explanation hypothesis is that in the northern hemisphere, both the Atlantic and the Pacific have surface seawater heat transporting currents that have a strong seasonal component. The southern hemisphere does not, simply owing to the present position of the continents.

And those plate tectonic induced seasonally varying NH currents explain Fig. 1. Seasonal Water insolation response in the mixed layer is similar. But the seasonal heat distribution is not.

Interesting. ristvan , let me colour this in a bit.

If it is ‘seasonal’ as in 12mo seasons, which I presume is what are referring to, it means that it is driven by extra-tropical regions. The lag you report seems to roughly coincide with the SST temperature cycle.

This suggests that the mechanism may be evaporation. Due to the major ocean gyres, most of the water exiting the tropics is on western side of the basin. Increased evaporation at highter latitudes will lead to an increase in the gulf stream.

Wasn’t the panic about the gulf stream slowing down and stopping due to the first measurements done in the 70’s when things were cooling?

Do you have a good link for gulf stream flow data?

This is testable. All Willis has to do is to use a finer grid than hemispheres. Knowing him a little, that’s probably what he is doing now.

ristvan,

My first thoughts were the gulf stream and the NH current in the western Pacific, both flowing north. The second thought was the proportion of cyclones and hurricanes in the NH (compared to the SH) oceans that remove a tremendous amount of heat from the waters. One other thought is just how much solar energy is being reflected off the waters due to low solar angles at different times of day and season (I’m still pondering that one).

Anyway, Willis has a way of getting us to think!.

Yes. My first thought was that aside from the amount of land in the NH, another major difference is the considerably different pattern of major ocean currents in the two hemispheres. Unfortunately the differences seem too complex for simple analysis.

Unfortunately the differences seem too complex for simple analysis.

Ristvan and others, thanks for your comments about the Gulf Stream. The best info that I can find on the monthly variations of the Gulf Stream is here, see Figure 8. It hightlights a couple of problems with your theory.

The first is the shape of the monthly changes. For nine months or so, there is no significant change in the gulf stream. Then for two or three months or so during the summer, it speeds up. This is unlike the change in the hemispheric ocean temperature.

A larger problem, however, is that the amount of heat transferred by the Gulf Stream only varies about ± 15% from the mean. This is far too small to explain the two-to-one difference in the sensitivity of ocean temperature to TOA insolation.

So we have bad timing (summer only, no change otherwise) and bad amplitude (not enough change) arguing against the idea that the Gulf Stream variations are the answer to the question.

I have some stuff to do today, but at some point I plan to take a look at the sensitivity on a gridcell-by-gridcell basis …

Thanks to all who are contributing,

w.

“So my question remains … why is the northern hemisphere ocean surface temperature twice as sensitive to a change in solar input as is the southern hemisphere ocean temperature?”

And another interesting question would be: “What effect does this have on global weather patterns under different conditions e.g an El Nino or La Nina year; more cloud/ less cloud; explosive volcanic eruptions?”

Ken S

Good question to ask (and admit you don’t know the answer).

my guess: a lot of the southern heat gets transported to the northern hemisphere? in the atlantic the gulf stream originates from the south… so that might explain it for the atlantic. The pacific is another story as there there are two distinct gyres that “should” distribute the heat north and south…

but then how does El nino and la nina play on these north south transfers?

but my guess is the huge thermohaline conveyor belt. The “hot part of it” run south-north to cool and sink in the arctic and flow back south again. so is it maybe in that direction that must be looked?

however imvho i don’t think it explains it all, but it could alredy be a part of the mechanics behind this odd paradox, this paired with a hotter air mass due to the land surface that heats air faster then a water surface. that for sure will also do something to parameters like cloud cover etc

Don’t bet on the “huge thermohaline conveyor belt!” To the extent that it can covey water masses without materially changing their temperature, it is a phenomenon many oders of magnitude slower than the wind-driven circulation. In fact, it’s so slow that what\s known about THC is almost entirely the product of theoretical computation, rather than empirical observation.

I think you will find that the THC is a lot faster at the surface than it is at depth – and it is surface flow that matters in this case (Gulf Stream, Humboldt Current, etc).

by my knowledge the gulf stream is pretty “fast” and so are all the currents that run “over the deeper laying conveyor belt. generally the top of the conveyor belt runs at 2.5 to 5 knots so it crosses every 4 day span an average distance of 400 knots (or nautical miles) so at peak it goes at 9 km/h and at slowest it goes around 4 km/h so at fast stretches it crosses a distance of 900 km every 4 days or 400 km every 4 days for the slow stretches. so the fast surface part of the conveyor belt averages out of crossing 6000 km every roughly 40 days. Seen the twists and turns the slow downs, it would make the southern water to run north in a timespan of roughly 3-4 months

note that this is for the fast flowing first 70-100 meters of that belt, the deeper you go the slower the conveyor belt goes. However the range of the fast part of the conveyor belt is in the same range as the mixed layer. so that makes that the summer heated water for the southern hemisphere reaches the northern hemisphere in late spring- early summer in the northern hemisphere for the atlantic. For the pacific this lag will be more important as there the distances are bigger to cross.

but like i said this is an “educated guess, following the logic of ocean current speeds and directions” as just one of the perhaps many mechanisms that drive this paradox.

Mike Jonas:

By definition, THC is produced by thermohaline density differences. Thus it is essentially a vertical, gravity driven motion. By contrast, the great surface currents, such as the Gulf Stream, Humboldt etc., are WIND-driven currents. The dynamical confusion perpetrated in climate science through its “conveyor belt” notion, which fails to recognize THC as a snail-paced, minor adjunct to the wind-driven circulation, constitutes one ot many dismal failures. of its paradigms.

Frederik Michiels:

Where did the fantastic notion that ” generally the top of the conveyor belt runs at 2.5 to 5 knots” originate? Certainly not in the work of oceanographers or in the observations of sailors. Such high current speeds may be observed with tidal flows in estuaries, but are wholly unknown in the open seas., where 2.5 knots is very fast even for the major surface currents during their peak season.

1sky1 – I have always understood that although the THC is driven primarily by density (‘Thermo’, ‘Haline’), the term “THC” covers the whole cycle (‘Circulation’), ie. including the surface currents. If I have got that bit wrong, just call the surface currents something else and my comments still apply.

Mike Jonas:

It’s only dynamically confused “climate scientists” who imagine that the wind-driven surface currents subduct virtually en masse in certain areas to produce a “conveyor belt” circulation. That’s why they foster empty fears that massive introduction of fresh water off Iceland will slow or shut down the Gulf Stream. Oceanographers recognize that no such thing can take place. THC is generated by rather diffuse sinking of high-density masses of water, which displacement produces compensatory flows to conserve mass (think continuity equation). In fact, Carl Wunsch, perhaps the leading expert on oceanic circulation, calls the notion of a coherent conveyor belt “a fairy tale for adults.” For a masterful layman’s explanation of THC, see: http://ocean.mit.edu/~cwunsch/papersonline/thermohaline.pdf:

Also just a guess but it seems reasonable that there is a net transfer of heat from SH to NH by currents.

Air temperature can’t do much as the cooled air would hug the sea surface and the warmed water would stay there. The water can heat the air but the reverse is working against convection.

The idea of warmed (or cooled) fresh water impacting the ocean temps makes sense but how different is the quantity and the heat content of the fresh water?

Possibility: Circumpolar Current is in the Southern Hemisphere which serves to keep colder water IN that current versus the mixing cause by the in and out Arctic currents.

+1

Hmm.. South Pole is colder than the North Pole. South P. Is at elevation whereas North P. is at sea level so lapse rate maybe comes into play. Otherwise, one would expect the greater temp gradient from equator to Antarctic should drive more rapid heat transfer until the temp difference resolves itself. Instead, the circumpolar current somewhat interferes with expected heat transfer? Circumpolar current can exist and remain stable because there is open ocean around Antarctica? So, if what I laid out here is agreeable, where does equatorial heat go in the Southern Hemisphere?

Could it be that the lay of the land in the Indonesian Archipelago sweeps La Nina piled water more to the North than the South? It appears that when the trade wind driven equatorial current reaches the Philippian islands, the current splits with the greater part heading North.

“The Pacific North Equatorial Current is given a westward impetus by the Northeast Trade Winds (latitude 10°–25° N). Upon reaching the Philippines, the current divides, with the lesser part turning south and then east to start the Pacific Equatorial Countercurrent, and the greater part flowing north. This flow, known as the Kuro Current, moves north as far as Japan, then east as the North Pacific Current (West Wind Drift), part of which then turns south as the California Current, which joins the equatorial countercurrent to form the Pacific North Equatorial Current.”

http://www.britannica.com/science/equatorial-current

I have pondered the thoughts posted so far. I still think this is a fairly simple answer having to do with the physical properties of the Earth’s land forms and the currents that swirl around them, the Coriolis effect, and fluid thermodynamics: the asymmetric ocean currents (due to land barriers and Earth tilt interacting with the Coriolis effect) and their corresponding asymmetric atmospheric correlates causing a greater temperature swing in the NH versus the SH because of cold Arctic outgoing currents mixing in the basins, and the asymmetric split of the warm Pacific North Equatorial Current favoring the NH seasonal swing.

One more thought: My suggested mechanisms have seasonal swings. The trade winds that drive or calm the equatorial currents have long been known to have seasonal swings, and clearly Arctic melt is seasonal.

Since the specific heat of seawater is the same in both hemispheres, with one calorie required to raise one gram by one degree Celsius, the notion of “hemispheric sensitivity” is a slippery one, at best. What we have is differential annual warming of very differently distributed water surfaces, subject to very different wind, wave and cloud regimes. There is no simple, direct relationship between TOA TSI and surface insolation, let alone thermalization of the oceanic surface. Nor do oceanographic data show in “any given location the mixed layer all has about the same annual average temperature.” While the annual cycle is far smaller than on land, the annual average varies enormously with latitude, Quite apparently, the effect of highly different oceanic coverage and wind speeds in the high latitudes of the two hemispheres overwhelms the relatively minor difference that TOA TSI might be expected to make on hemispheric SST averages. .

The ‘average’ land (or ocean) in the Northern hemisphere is not at the same latitude as the ‘average’ land (or ocean) in the Southern hemisphere?

Instead of dividing the hemispheres at the equator, at what latitude would the division be, in order to equalise the two sectors? I really don’t know what this might imply. It’s just an idea looking for alternate clues.

Use the 10.6 cm Flux as a proxy for Solar energy actually reaching the Earth.

In addition, as per Pamela -> Possibility: Circumpolar Current is in the Southern Hemisphere which serves to keep colder water IN that current versus the mixing cause by the in and out Arctic currents