Guest Post by Bob Tisdale

This post compares the responses of global surface temperature anomalies and lower troposphere temperature anomalies for the 2015/16 El Niño and the comparatively strong 1997/98 El Niño. Datasets included are lower troposphere temperature data from RSS and UAH and land-ocean surface temperature products from NASA GISS, NOAA NCEI and UK Met Office.

INTRODUCTION

Referring to the sea surface temperatures of the NINO3.4 region of the east/central equatorial Pacific, the current 2015/16 El Niño is comparable in strength to the 1982/83 and 1997/98 El Niños. Due to the differences between sea surface temperature datasets, however, it is impossible to know which El Niño is actually the strongest. (See the post here.)

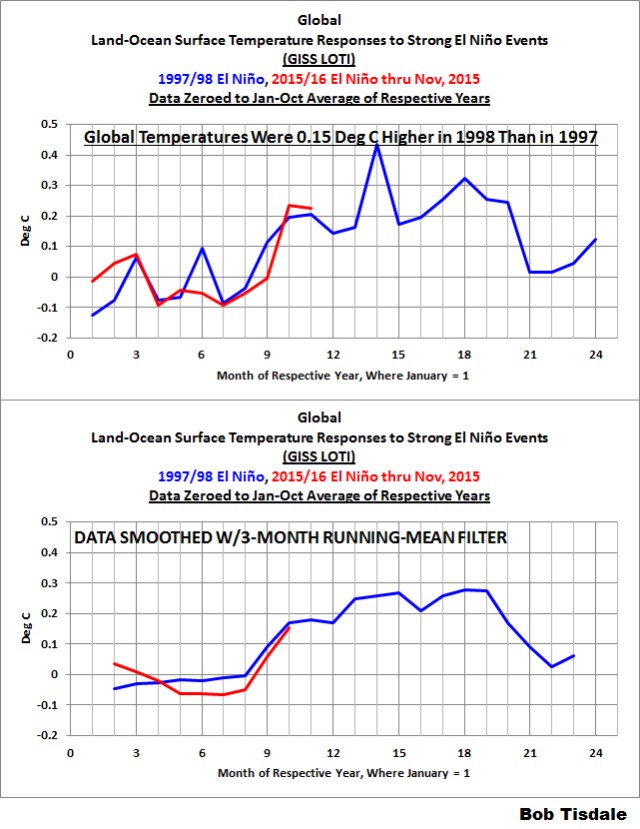

In this post, we’re comparing the evolutions of global surface temperature anomalies (GISS LOTI, NOAA NCEI, and UKMO HADCRUT4) and lower troposphere temperature anomalies (RSS and UAH) for 24-month periods starting in 1997 and 2015. We’re excluding the responses to the 1982/83 El Niño because the 1982 eruption of El Chichon impacted global surface temperatures in those two years. To better align the data for comparison purposes, the data are referenced (zeroed) to the average temperature anomalies for the January to October of 1997 and 2015. The top graphs in each of the figures include the monthly data. Due to the volatility of the some datasets, the bottom graphs include the data smoothed with 3-month running-average filters. I’ve listed the global temperature difference between 1997 and 1998 in the top graphs, so that you can get an idea of the expected rises in global surface temperatures from 2015 to 2016.

Due to data availability, the end months of the data in 2015 vary.

Let’s start with the…

LOWER TROPOSPHERE TEMPERATURE ANOMALIES

The RSS lower troposphere temperature (Figure 1) data are here. The RSS data run through December 2015. The UAH data (Figure 2) are here. The UAH data end in November 2015 as of this writing.

Figure 1

# # #

Figure 2

We should expect lower troposphere temperatures to continue to rise through March/April of 2016 and then decline through 2016…and then continue to drop into 2017 in response to the 2016/17 La Niña, assuming one forms (reasonable assumption).

LAND+OCEAN SURFACE TEMPERATURES

Figure 3 includes the GISS Land-Ocean Temperature Index (data here). The NOAA/NCEI land+ocean surface temperature data (here) are shown in Figure 4. Both the GISS and NOAA data are available through November 2015. The UKMO as of this writing still have not published their November 2015 HadCRUT4 data (here), so they end in October in Figure 5.

Note that the scales of the y-axis are smaller in Figures 3 to 5 than they were in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 3

# # #

Figure 4

# # #

Figure 5

We might expect the global surface temperatures to peak in February or March of 2016, assuming 2016 surface temperatures mimic those of 1998. Surface temperatures remained elevated through to the second half of 1998, when they began to show noteworthy drops. Once again, we could expect surface temperatures to continue to drop in 2017 is response to the 2016/17 La Niña…if one forms, which is likely.

CLOSING

The responses of global surface and lower troposphere temperatures in 2015 are what we would expect for a strong El Niño. In 2016, if global surface and lower troposphere temperatures continue to respond as they had to the 1997/98 El Niño, we can expect global surface and lower troposphere temperatures to be higher in 2016 than they were in 2015.

I’ll try to update these graphs every couple of months.

FOR THOSE NEW TO DISCUSSIONS OF EL NIÑO EVENTS

I discussed in detail the naturally occurring and naturally fueled processes that cause El Niño events (and their long-term aftereffects) in Chapter 3.7 of my recently published free ebook On Global Warming and the Illusion of Control (25 MB). For those wanting even more detail, see my earlier ebook Who Turned on the Heat? – The Unsuspected Global Warming Culprit: El Niño-Southern Oscillation. Who Turned on the Heat? only costs $5.00 (US).

Dr Spencer has a recent post on “what Causes El Nino Warmth” which is also worth checking out:

http://www.drroyspencer.com/2016/01/what-causes-el-nino-warmth/#comments

Thanks, Richard. Quite helpful.

So the warming/cooling during +/- ENSO could mostly be due to less/more plankton growth due to having less/more nutrients due to decreased/increased upwelling respectively. There are so many intertwined variables in climate.

http://www.realclearscience.com/journal_club/2015/07/18/how_plankton_produce_clouds_109309.html

In case anyone is interested, there’s an excellent demolition of Jan Perlwitz and his cognitive dissonance in the comments section there. The guy was left blubbering an appeal to the nomenclature of forcings vs. feedback before he apparently resigned.

I bring this up because the arguments used by Kristian and mpainter are spot on, and exactly what are required to demolish this scientific fraud.

Bob,

This is terrific, as usual. Among the best analysis I’ve seen about this El Nino.

Do you have any thoughts about the likelihood of this El Nino creating a lasting step-change in the global average temperature?

Editor of the Fabius Maximus website, I suspect we’ll see an upward step in the sea surface temperatures of the East Indian and West Pacific Oceans…and, in turn, the South Atlantic, Indian and West Pacific. All of the leftover warm water released by the El Nino has to go somewhere and the likely place for it to initially wind up is those regions.

The North Atlantic is another matter, though, with the AMO appearing to have peaked.

Bob,

Thanks for the forecast! Speaking of the AMO, Philip Klotzbach tweeted this today (he is a meteorologist at CSU specializing in Atlantic basin seasonal hurricane forecasts). @philklotzbach

Bob,

If I may: –

First sentence or so:

“This post compares the responses of global surface temperature anomalies and lower troposphere temperature anomalies for the 2015/16 El Niño and the comparatively strong 1997/98 El Niño.”

Possibly

This post compares the responses of global surface temperature anomalies and lower troposphere temperature anomalies for the 2015/16 El Niño and the comparably strong 1997/98 El Niño.

Do consider – fixed it???

Auto, not sure I should review your choice of word . . . . . .

Speaking of AMO, it peaked wicked high at the same time temps peaked during the el ninos of 1998 and 2010. Don’t think that is going to happened this time. AMO with el ninos high lighted (approx.):

http://woodfortrees.org/plot/esrl-amo/from:1996.6/to:2015.3/plot/esrl-amo/from:2015.2/plot/esrl-amo/from:1997.29/to:1998.4/plot/esrl-amo/from:2009.58/to:2010.33

The issue here is whether there will be a long lasting step change in temperatures coincident with the current 2015/16 strong El Nino, as there was a long lasting step change in temperatures coincident with the Super El Nino of 1997/98, or whether the current El Nino will result in a short term spike (and nothing more) as did the 2010 El Nino.

If there is no long lasting step change in temperatures coincident with the current strong El Nino what is likely to happen is that over the next 4 months, there will be a short lived spike, and then the following La Nina in late 2016/early 2017 will bring temperatures down again, and following that La Nina temperatures may well stabilize around the 2001 to 2003 level going forward into 2018/19.

If (and this is only an if) that happens then in the immediate lead up to AR6, the ‘pause’ will be more than 21 years in duration, and it is likely that in this scenario, every model, or all but a few, will be outside their 95% confidence bounds. This will make AR6 problematic. Particularly, since in this scenario, it is likely that there will be a number of papers published in 2018/19 suggesting ever lower figures for Climate Sensitivity; as the ‘pause’ continues and lengthens, Climate Sensitivity must come down.

So unless there is a long lasting step change in temperature coincident with this current strong El Nino, and not simply a short lived peak 9even if that peak is above the 1998 peak), this current El Nino will be seen to be a dud. I say that not to detract away or minimise the ordinary consequences of strong El Nino on weather patterns globally and more specifically regionally which can and will no doubt be significant, but rather in the context of cAGW. To keep cAGW alive, the warmists require the satellite record to show some long term warming, and it looks likely that (in the short term) this will only happen if there is a long lasting step change in temperature coincident with the 2015/16 El Nino similar to the one that took place coincident with the 1997/98 Super El Nino.

Richard,

I agree I all points, but couldn’t say them so well.

The La Nina of 1999-2001 occurred during SC23 maximum. That’s a fact.

Keep in mind the meteorological conditions of a La Nina: Cold water upwelling presented on the surface, clear skies, thus lots of SW solar radiation penetration to depth, i.e. a heat recharge event. That recharge if it is strong could presumably blunt the cooling of the La Nina. A concurrent strong solar max during a La Nina may keep in place some portion of the temp step-up change that resulted from El Nino heat release to the rest of the system, the 97-98 step up event.

The 2016-17 La Nina (a reasonable assumption) will occur during the wind down of SC24 to its minimum in late-2018 or 2019. The step change may be down, not up with La Nina 2017.

ENSO has of course been running for many millennia. If there were only step-up temp shifts, the oceans would be boiling by now. Climate system feedbacks and the random interplay between solar cycle mins/maxes and coupled ocean-atmosphere climate cycles ultimately ensures reversion to mean and a stable temperature.

According to Dr. Spencer there is a decrease in total cloud cover caused by circulation patterns (and I think lack of nutrient availability to plankton) during El Nino and this causes the warming during El Nino.

http://www.drroyspencer.com/wp-content/uploads/Spencer-Braswell-2014-APJAS1.pdf

The stepwise increase in global temperature after a strong El Nino like the 97/98 is more likely due to the fact that the timing occurred at the end of a 30 year history of generally increased El Nino activity, positive PDO.

Solar variability does not have immediate impacts on global average temperature and is instead important in multidecadal periods itself, where the difference between a 30 year period of high or low solar activity could mean a difference in more than 10^23 joules of energy hitting the top of the atmosphere. This is just the direct change in total irradiance and extended periods of high or low solar activity probably result in a larger difference in energy balance with the culmination of solar variable effects.

The current solar cycle was the first cycle since the 1920s that would be considered a weak cycle relative to the ones that have been observed since the 1600s. The next solar cycle has been forecast to be weak even before this current solar cycle began and is now forecast to be very weak. I’m not sure if this decrease will have much impact by 2018 but the PDO may be in the middle of a negative trend. The AMO is currently positive may be nearing the end of that trend.

If the AMO turns negative, the PDO returns to negative, and the next solar cycle is a dud, we should be seeing the end of the hiatus with a downward trend in global temperature after 2020. Even if all three of these don’t coincide, I doubt there will be another stepwise increase and the hiatus will continue.

Richard Verney – I hate to disappoint you but super El Ninos are rare and the coming El Nino is not one of them. It it fits in nicely with the 2010 peak and both are part of the ENSO oscillation. As a result there will not be a temperature step like the one that followed the last super El Nino at the turn of the century. That super El Nino itself was not part of the ENSO oscillation. Pull down the current UAH temperature chart that Roy Spencer puts up to see this. To the left of the super El Nino is an ENSO wave train of five El Nino peaks. Unexpected arrival of the super El Nino cut it short. The base of the super El Nino itself is only half as wide as the bases of the others but it is almost twice as high. You need a satellite view like that from UAH to see this distinction because ground based temperature curves lack the required resolution. ENSO is an oscillation of ocean water that sloshes back and forth between the east and the west sides of the Pacific Ocean. It has a period of about four or five years but this can be disturbed by other happenings in the ocean. As a result, the actual period can vary between three and nine years per cycle. We have five such cycles here, each one corresponding to a separate back-and-forth motion of the ocean waters. But then on top of ENSO comes the super El Nino. It carries an abundance of warm water with it that cannot be derived from the same source that the other peaks use because all of it is bespoke for. That extra warm water must come from a more distant source that is presently unknown. And without that extra warm water of the super El Nino a step warming like that at the turn of the century is impossible.

“That extra warm water must come from a more distant source that is presently unknown.”

Unknown??? Not if you think GEOLOGICAL. Geologist, James Edward Kamis presents a fascinating new theory as how volcanic activity and other geothermal impacts play a previously ill-considered role on earth …

http://www.climatechangedispatch.com/what-s-fueling-the-current-el-nino-and-it-s-not-global-warming.html

Hello Bob and Fabius.

Thank you Bob for your articles.

I think we will see a downward (cooling) trend, starting as early as 2H2017.

Regards, Allan

http://wattsupwiththat.com/2015/12/31/montreal-record-busting-snow-sours-the-mild-winter-climate-narrative/comment-page-1/#comment-2110997

[excerpt]

Care to estimate when global cooling will be apparent in the satellite Lower Troposphere (LT) temperature data?

My best guess based on conversations with my knowledgeable friends, is some time in 2017.

That will, of course, require some time thereafter to confirm it is not just a downward blip – but I am guessing that 2017 will be the inflection year that clearly exhibits, in the satellite LT data, the start of a multi-decadal global cooling cycle.

Please look at Dan Pangburn’s temperature (climate?) model, which suggests that global cooling is overdue – except for the temporary effect of the current El Nino.

Dan Pangburn’s temperature model is at

http://agwunveiled.blogspot.ca/

See Figure 1.1

Now if only someone could figure out what phenomenon is happening. The Rumplstiltskin effect is seemingly in play–we have a name for that unknown but well described thing, and tend to think we have made the mystery go away. The graphs track each other so well it clearly looks like the same thing is happening, but WTF is it?

http://www.climatechangedispatch.com/what-s-fueling-the-current-el-nino-and-it-s-not-global-warming.html

Tom Halla, the processes behind the phenomena of El Nino and La Nina aren’t too difficult to understand. I used more than 30 cartoon-like illustrations to explain them here:

https://bobtisdale.wordpress.com/2014/01/10/an-illustrated-introduction-to-the-basic-processes-that-drive-el-nino-and-la-nina-events/

And I also described and illustrated the processes in Chapter 3.7 of the ebook here:

https://bobtisdale.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/tisdale-on-global-warming-and-the-illusion-of-control-part-1.pdf

Cheers.

Mr Tisdle,

The cartoons describe what should be an annual event but the cycle is not an annual one. That is because the heat source is geological as described here.

http://www.climatechangedispatch.com/what-s-fueling-the-current-el-nino-and-it-s-not-global-warming.html

Yeah, but no pop-up pages 😉 (wink)

Is anyone researching what it is? I think so.

http://www.climatechangedispatch.com/what-s-fueling-the-current-el-nino-and-it-s-not-global-warming.html

The remarkable similarity between the 97/98 and the current El Nino inspires confidence in the reliability of the data and their interpretation. The two El Nino events show repetitive behavior suggesting an established cyclic phenomenon. Apparently, the “Decadal Oscillation” has been aptly chosen. That kind of quantitative information is a must to anyone seriously interested in the climate variability. Unfortunately, the general public will never see any of that because the media filters it all out and substitutes the mindless mantra “we will all fry” for it, that filtering apparently includes the Science Advisor to our President.

Jaroslaw Sobieski, Hampton, VA

JS,

Probably OT, but since you mentioned Hampton, VA, I was wondering if you work or worked at LArC (if it’s not too personal information)? I have a friend who works at LArC, so just curious.

LaRC, not LArC.

Meanwhile I sit here in the third straight day of non-stop rain on the East coast of NSW, wondering where this so-called “El Nino” has gone. First time since 1993 that the Sydney test has been rain interrupted (at all) and first time since 1976 that it’s been rain interrupted for more than two days.

Then I think back to January 1998 and how it was impossible to leave the air conditioned rooms of the house without suffocating in the heat of two and a half weeks above 38C and I wonder what is being missed from the El Nino equations. It’s just not affecting the East Coast like the others.

How many ‘Phil’ s may there be here?

Auto [not a Phil in real life].

have a look at what the wind did with the “heat” during the 97/98 event, then look at what the wind is doing this time around. therein lies your answer. the only temp spike that will happen this time round will be a manufactured one on charts and graphs. oceanic oscillations at very different stages this time round.

For where I live 38C is a below average summer day we have about four months of plus 38 C temperatures our average is closer to 40C with 45 C not unusual. Of course where I grew up 38 C was unusual but not unheard of as were 45 C is generally near a record. I use to live in North Dakota/Minnesota and have moved down to Arizona. Giving up winter’s -40 C is difficult but I have adjusted somehow down here when the weather people state that 0C is extreme cold somehow I find that funny.

For what it is worth I remember the 1982/83 El Niño very well as it had a greater influence on my local weather than the subsequent two. I am a grassland farmer as well as a geologist. We don’t forget notable years. 82/83 was extreme. The current and, the 98 El Niños, are moderate by comparison. I would love to see sea surface temperatures from the 82/83 event

Michael C, here’s a link to evolution comparisons of NINO3.4 region sea surface temperature anomalies using different datasets:

https://bobtisdale.wordpress.com/2015/11/21/the-differences-between-sea-surface-temperature-datasets-prevent-us-from-knowing-which-el-nino-was-strongest-according-nino3-4-region-temperature-data/

Cheers.

Bob – thanks. The 82-83 event was SO different to any other year in my living memory> All the deciduous trees that flourished happily here had their leaves stripped off by strong SW winds and skiffy showers throughout summer. They did not recover until the following season. The east coast of NZ had disastrous drought. We have the same pattern this year but with nowhere near the same grunt. Its a baby by comparison

Any updates on the upwelling kelvin wave progression. When did the 97/98 el nino end, or start breaking up? How might this one play out if the upwelling wave snuff the el nino earlier, do we end up with another pacific warm blob and less tropospheric warming? If we don’t have strong westerlies, and the circumpolar vortex weakens, how might arctic blasts interact with el nino remnants?

aaron, for the latest progress on the upwelling Kelvin wave, see pages 12 and 15 of NOAA’s Weekly ENSO Update:

http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/lanina/enso_evolution-status-fcsts-web.pdf

NINO3.4 region sea surface temperature anomalies peaked in December 1997 and NINO3 region anomalies peaked a few weeks earlier. Both reached zero in June of 1998.

Here’s the new look of my weekly NINO region SSTa comparisons for the 1997/98 and 2015/16 El Niños. I’ve extended them another 40 weeks to capture most of the second years.

I can’t answer your last two questions.

Cheers.

Note that in 1997-98, the Nino 3.4 peaked in month 12 (mid-December) but the temperatures did not peak until month 15 or 16.

And the temperatures in the 2015-16 El Nino example are following the same pattern (except the peak Nino 3.4 was probably mid-November or 1 month earlier than 1997-98).

So peak temps are likely to be in month 14 or 15 from the start of 2015 or February or March 2016.

Thanks, Bob and Bill.

Looking at the page 12, my intuition is that the progression of the kelvin wave has been stopped by the el nino.

There are 03dec15 easterly wind bursts though. That’s interesting.

I should try to find a similar report for dec 97 to compare.

Never found the comparable 97 report.

On second thought, this is just temp anomaly. Maybe the el Nino just hides the wave, when it reaches SA it will reinforce upwelling and maybe cause surface cooling and shift winds.

I am very curious as to why the 4 balloon datasets never seem to be used in any analysis

http://www.globalwarming.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/CMIP5-73-models-vs-obs-20N-20S-MT-5-yr-means1.png

Eliza, there are two answers to your good question. 1. They are just not here. For example, radiosonde estimates are used to inform the ERA reanalysis, which Glenn Paltridge used in his 2009 upper troposphere humidity paper. 2. They are not used directly for global surface temperature anomalies. A. The data is at altitude. B. Coverage is too spotty.

But, they are very usefull for verifying satellite troposphere temperature estimates, and for showing the absence of the modeled tropical troposphere hotspot. That is how UAH uses them, and why John Christy plots them separately on the chart in your comment.

Eliza,

A good question.

Any good engineer would tune the computer models to match the data.

I guess the data does not serve their purpose, so violate all good scientific practice and continue the fraud

Here would be an example where the radiosondes going back 1958 are also used as in appended to the same height lower troposphere temperatures from UAH and RSS. (I’ve also removed the natural variation from the ENSO, the volcanoes, the AMO and the solar cycle).

Versus the climate model forecasts from IPCC AR4 – 1900 to 2100.

This is now the best comparison available now because they are adjusting the surface temperature record so furiously right now because the raw values are so, so far off the global warming theory projections.

The other issue here is that the troposphere is supposed be warming 30% faster the surface (the model forecasts in this case) so they should really be adjusted upwards by another 30% trend. That would be pointless of course since they are so far off already.

http://s30.postimg.org/ppsz7srz5/IPCC_AR4_vs_Trop_Nat_Var_2100.png

This also shows why the

I still suspect that El Nino 2015/16 is quite dissimilar to 1997/98 (ref. the Nino 1+2) graph above. If not quite a Modoki (Central Pacific) El Nino, it still has obviously failed to deliver as much warm water to the S American coastline as did 1997/98. For this reason, I suspect the LT global temp response may be somewhat more muted in 2016 than in 1998. But I could be totally wrong. For sure, if the response is more or less the same, we will see a record in the LT by some margin. Here’s an interesting comparison of 1997 and 2015:

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=4773

Thanks for the link, Jaime.

I agree that October 2, 1997 looks different from October 1, 2015 in the November 19 ’15 article you link.

What to make out of it? I certainly don’t know.

Similar comparison articles:

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/spaceimages/details.php?id=PIA20009 is from October 19 ’15.

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=4808 is from December 29 ’15.

A question.

Past GISS numbers have been adjusted over the years.

What might some of the graphs look like using the past GISS values for ’97/’98?

Ristvan Thank you

You are welcome. After 6 years and parts of three ebooks, I do understand most of the ‘shapes’ if not yet all the ‘details’ of this debate. Your very good question was another example of the FUD warmunists spew. Essays Humidity is Still Wet and Models all the Way Down provide some more background, with references.

Bob Tisdale

I know there is lack of good SST data and El Ninos once you go earlier than say 1900 , but how did the 1877/78 strong El Nino compare to say 1997/98 or 2015/16 El Nino. There were land temperature spikes of 2-3 degrees C for Canada and North America at that time. Ontario , Canada had spike of almost 4 degree C.

Not only was it hot during 1877/78 in North America but it was hot with droughts all over Asia, South America , Australia, etc.

http://joannenova.com.au/2015/01/forgotten-extreme-heat-el-nino-of-1878-when-miners-yearned-for-the-years-when-theyd-knock-off-at-44-4c/

showing the temperature spike during the El Nino 1876-1878 in Ontario Canada

http://berkeleyearth.lbl.gov/auto/Regional/TAVG/Figures/ontario-TAVG-Trend.pdf

Bob

You will recall your chart below . Note the 1877/78 EL NINO

http://tinypic.com/view.php?pic=2588hhe&s=3#.VosZNTZIjFQ

Your original work on this . Note the 1877/78 NIN3.4 readings in comparison to 1997/98

http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/gcos_wgsp/Timeseries/Data/nino34.long.anom.data

herkimer, you’re right. There is too little source data along the equatorial Pacific before the 1900s to make the comparison worthwhile. Here’s a map of the observations in December 1877:

http://climexp.knmi.nl/ps2pdf.cgi?file=data/g20160105_1248_11018_1.eps.gz

Cheers

BOB TISDALE

Bob,I think some comparisons could be made .

http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/gcos_wgsp/Timeseries/Data/nino34.long.anom.data

According to NOAA source above and using NINO 3.4 data , the 1877/78 El Nino was the strongest up to OCT 2015

HIGHEST NINO 3.4 READINGS

1877/78 2.51

1982 /83 2.45

1988/87 1.63

1997/98 2.5

2015/16 2.26 (to OCT 2015)*

*It could be that NOV/DEC figures may take the current El Nino higher . The latest figure could be 2.85 for December 2015

My point for bring this issue up is that we have had comparable El Ninos to the present going back some 138 years and the1997/ 1998 El Nino was not the only previous biggest El Nino.

herkimer

Bookmarked. Thank you.

RA COOK PE 1978

I have fine tuned the five highest Nino 3.4 readings and you should bookmark this instead.

5 HIGHEST NINO3.4 ANOAMLY READINGS

2015/16 ELNINO (2.95 ) NOV/2015 ( was 2.46 in Oct and started to decline in December 2015)

1877/78 EL NINO ( 2.51) DEC/1877 ( was the historical highest until November 2015)

1997/1998 EL NINO ( 2.5) NOV/ 1997

1982/1983 EL NINO (2.45) JAN/1983

1972/1973 EL NINO (2.22) DEC/1973

Until November 2015 , the1877/78 El Nino had the highest Nino3.4 anomaly reading. I my judgement they are all of about the same level and the differences are minor .

Any idea what physical process might make a ceiling?

================

Off Topic Open Questions —

I note that above and beyond the default allowed HTML in the WordPress comments section that some post images and embed videos in their comments. Can someone provided me with the code for either?

Does HTML code for opening links in a new browser window or tab work in the WUWT comment section?

Do you have a favorite HTML editor for composing a comment so that it can be viewed before posting?

Please visit the WUWT test page for guidance and a place to experiment. See the top Nav bar or go to http://wattsupwiththat.com/test/

In general just post the URLs you want (put images on their own line) and WordPress will display the image or create a link. Most decorations on HTML don’t work, so you can’t post a link that opens in a new tab (AFAIK, try it).

For an editor, I have the It’s All Text plugin so I can edit comments with emacs. It’s no help as a HTML preview, use the test page.

David have a browse through the ‘test’ tab at the top of the page most ways of editing posts are there I think

Thanks mwh.

Bob:

http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/enso/sub_surf_mon.gif

Is there enough hot water volume to do much more warming? The warm water seems to be thinning <100m with an aggressive wedge of cold water pushing up from below. I suppose several hear could calculate how much heat there is in this thinning volume to be spread around the world.

Evolution in Climate Science is a fact. As evidenced by the constant ‘evolution’ of historical climate measurements to support ‘climate change’.

Um, why are they zeroed against different years? Show the anomalies as they are. Are you trying to hide just how much warmer it is now compared to 1997? Does the difference go against your pause narrative?

it looks like you don’t even read Bob tisdales work. He never made a pause narrative but in contrary states that the warming we see is step-driven by strong el nino’s. he’s even the first person that made the prognose in question form that this el nino may cause together with the blob a new climate shift as seen in 1975-1976. Sorry Daveo it looks like you have some reading work to do

When you compare an el nino in strength then it is normal you “zero” them, as a nino anomaly comparison works like this in this fictive plot with units:

el nino 1 starts at zero anomaly and goes up to + 3 units

el nino 2 starts at +0.5 anomaly and goes up to + 3.2 units

this makres e nino 1 at +3 stronger then el nino 2.

in this fictive example the el nino 1 would be stronger then the other one as it made a signal of 3 units instead of 2.7 units of the second one of this fictive example, even if in the graph the second one would look higher at 3.2 units, the “net nino signal” is lower. Also as this is a ongoing signal in time it is also good to zero them to see how el nino’s evolve compared to other el nino’s

that’s why it’s “zeroed” as otherwise you can’t compare them.

Interesting facts here. El Nino events should be better annalysed in other to understand them. You all know that climate alarmists have run wild with predictions about the Monster El Niño active in the Pacific for several months. A corresponding situation existed in late 1939, and here are more details about that: http://oceansgovernclimate.com/storm-frank-el-nino-insufficient-explanation/.

SMAMARVER

It is interesting that you bring up the cold European winter period 1939/1941 and the El Nino of that time . Eastern North America had a winter similar to the late 1939/ 1940 European winter during winter of 2014/2015 (during the 2014/2015 El Nino). There was also a very high NINO3.4 reading during the 1939/41 period comparable to the 1877/78 Nino reading ( see earlier posts by me ) Both of these strong El Ninos and high Nino3.4 SST temperature levels were followed by 30 years of cooler global weather( 1878-1920 and again 1940-1980) The 2015/16 strong El Nino could be the start of the next cool phase which could run to 2035 /45. ?

Regarding El Nino: The are a number of factors that I am unclear about. Let’s get back to simple logic

What we know with a great deal of certainty is that:

1: El Nino events result in an increase in temperature within ‘cells’ in the tropical Pacific

2: This results in an increase in mean global SST (or does it?)

3: Warm water rises rapidly to the surface zone (of say 100m depth)

4: Ocean currents and tidal dynamics mixes and sorts various water temperature zones in a semi-chaotic manner

5: Marine current conveyer systems can cause an upwelling of cold water

Now, either:

El Nino is a result of a temporary increase in heat energy input into the ocean

Or

El Nino is a result of a concentration of warmer water through a periodic change in the mixing, currents, and/or convection systems

The written record appears to favour the second possibility

But: what is this mechanism that results in such a significant pulse? Why should such a large cell of significantly warmer water assemble with such regularity? How can this happen? Imagine that the warm water is say oil that is distributed in a certain manner during La Nina and then rapidly concentrated during El Nino due to some change in convection and mixing. Explain to me how this could happen. It is not making sense

Now for some arm waving: that El Nino is triggered by some external cyclical energy forcing, the most likely being tectonic – the ring of fire. There is a lot of work to be done in regards to heat energy contribution from mid ocean ridges (MOR) and submarine volcanoes. The Pacific seabed is littered with active vents. This includes the most extensive MOR on earth plus hot spots (Hawaii) and a chain of explosive silicic volcanoes extending from New Zealand to Tonga. A large percentage of these are active

If we look at the charts posted by Gary Pearse, above we see a thinning towards the east – just as we would expect should the hear source be in the west and that currents are carrying the warm water towards the east

I want to know a lot more before accepting the current hypothesis

Regarding El Nino: The are a number of factors that I am unclear about. Let’s get back to simple logic

What we know with a great deal of certainty is that:

1: El Nino events result in an increase in temperature within ‘cells’ in the tropical Pacific

2: This results in an increase in mean global SST (or does it?)

3: Warm water rises rapidly to the surface zone (of say 100m depth)

4: Ocean currents and tidal dynamics mixes and sorts various water temperature zones in a semi-chaotic manner

5: Marine current conveyer systems can cause an upwelling of cold water

Now, either:

El Nino is a result of a temporary increase in heat energy input into the ocean

Or

El Nino is a result of a concentration of warmer water through a periodic change in the mixing, currents, and/or convection systems

The written record appears to favour the second possibility

But: what is this mechanism that results in such a significant pulse? Why should such a large cell of significantly warmer water assemble with such regularity? How can this happen? Imagine that the warm water is say oil that is distributed in a certain manner during La Nina and then rapidly concentrated during El Nino due to some change in convection and mixing. Explain to me how this could happen. It is not making sense

Now for some arm waving: that El Nino is triggered by some external cyclical energy forcing, the most likely being tectonic – the ring of fire. There is a lot of work to be done in regards to heat energy contribution from mid ocean ridges (MOR) and submarine volcanoes. The Pacific seabed is littered with active vents. This includes the most extensive MOR on earth plus hot spots (Hawaii) and a chain of explosive silicic volcanoes extending from New Zealand to Tonga. A large percentage of these are active

The charts posted above by Gary Pearse show a thinning to the east just as what we would expect if the heat source was in the west during the existence of an easterly current

I want to know a lot more before accepting the current hypothesis

Michael C. So would I want to know a lot more. Most of what you read here is puff and guff.

It has long been known that a falling off in the trades (and the Westerlies because they come from the mid latitude high pressure cells) is associated with a reduction in the flow of cold waters into the ENSO 1 and 2 regions and across into the ENSO 3 and 4 regions.

Back one step: What causes surface pressure to fall in the mid latitudes. Answer: A return of atmospheric mass from mid to high latitudes.

Back one step: What causes atmospheric pressure to increase in high latitudes? Answer, a reduction in the ozone partial pressure in the high latitude atmosphere.

Back one step: What causes a reduction in ozone partial pressure in high latitudes? Answer: An increase in the flow of mesospheric air containing erosive NOx that depletes ozone in the stratosphere, a flow that occurs inside the polar vortex. The flow is greatest in winter at a time when ozone partial pressure peaks on the perimeter of the vortex. It peaks due to a reduction of the rate of photolysis of ozone at low sun angles. The presence of peak ozone creates a convective overflow that pulls in air from the mesosphere over the pole. There is a very large inter-annual variation in ozone partial pressure from year to year and decade to decade in the winter-spring months in both hemispheres.

Polar cyclones are cold core at the surface and warm core aloft. A cyclone of ascending air requires warming somewhere in the atmospheric column to initiate convection. You can initiate convection in a chimney by placing a candle between half way and the top of the chimney. Ozone is a potent greenhouse gas absorbing at 9-10 micrometers, a wave length at the centre of the range of infra-red energy emitted by the Earth. It is ozone that is responsible for the elevated temperature of the stratosphere. All that you need to start a convective stream is a steep local gradient in air pressure between very cold dense and warmer less dense air. That steep gradient is established between air of the stratosphere proper and cold air inside the polar vortex. The wind so created is called a Jet Stream. Fierce winds are powered by ozone heating using the energy from the Earth itself on the margins of the polar night zone. More at: https://reality348.wordpress.com or read up on the ‘Annular Modes’, or the Arctic Oscillation.

.

Erl – Thanks

My understanding of the ENSO dynamics is still in its infancy. My conclusion from your explanation is that warm water accumulates and migrates in a particular fashion due to change in wind patterns. The wind patterns are subject to cyclical forcings involving ozone and polar cyclones

There is one possible flaw in this theory: why is the phenomenon confined the Pacific? Why not in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans too?

Cheers

Michael Carter

Hi Michael. Great question. The cyclical forcings due to the flux in polar cyclone activity arise at the poles in both hemispheres in winter so six months apart.

ENSO (El Nino Southern Oscillaltion) is a phenomenon first noticed by Gilbert Walker who was trying to understand the variation in the Indian Monsoon. He noticed the swings in surface pressure between Tahiti and Darwin and this is still a good proxy for the change in temperature in the ENSO 3.4 region leading by some months and so predictive. The warming phenomenon that we call El Nino manifests in all oceans but nowhere as strong as in the Pacific. The extreme manifestation that occurs in the Pacific is due to geography:

1 The extent of the Pacific Ocean occupying so much of the tropical latitudes.

2 Extremes in surface pressure at both ends. The South East Asian end collects warm water and produces low surface pressure. The eastern end sports high pressure cells that occupy enormous areas and these cells bear the brunt of the shifts in atmospheric mass driven by the flux in ozone in high latitudes. When ozone partial pressure falls, mass shifts from the high pressure cells of the mid latitudes (Eastern Pacific in particular) back to high latitudes and vice versa. So, the Pacific is the canary in the coal mine…. experiencing the most vigorous change.

But the ENSO phenomenon gets too much attention. Its a response to change elsewhere. The tropics cool as the mid latitudes warm. Change in the tropics dominates the global temperature statistic because the area is so large and the swing in temperature resulting from a simple mixing process driven by the winds is massive. The real action is elsewhere but it is concealed because the surface of the ocean changes very little in its temperature due to the transparency of water, light energy absorbed down to as much as 300 metres in depth. When the cooling event associated with increased wind pressure due to increased surface pressure in the mid latitudes is over, lo and behold, there is more energy in the system, the winds settle down again, less cold water is pushed into the tropics but its seen to be warmer there than prior to the apparent cooling event. This upwards step change is part of the warming cycle. As we get into a cooling cycle we will see a downwards step change….could manifest shortly.

So, its smoke and mirrors really and we fall for it every time.

The change in surface pressure in the mid latitudes reflects a change in the area and clarity of the clear sky window associated with high pressure cells that lie over cool waters on the eastern sides of the oceans. In this zone, evaporation exceeds precipitation. On adjacent landmasses we have deserts.

Erl – thanks

I will digest it over time

M

That’s a pleasure. For the background visit https://reality348.wordpress.com/ , where you will find a work in progress. ENSO comes in Chapters 27 and 28. Currently I am at Ch 4. You have the abbreviated version above.