Guest Post by Willis Eschenbach

Although it sounds like the title of an adventure movie like the “Bourne Identity”, the Bern Model is actually a model of the sequestration (removal from the atmosphere) of carbon by natural processes. It allegedly measures how fast CO2 is removed from the atmosphere. The Bern Model is used by the IPCC in their “scenarios” of future CO2 levels. I got to thinking about the Bern Model again after the recent publication of a paper called “Carbon sequestration in wetland dominated coastal systems — a global sink of rapidly diminishing magnitude” (paywalled here ).

Figure 1. Tidal wetlands. Image Source

Figure 1. Tidal wetlands. Image Source

In the paper they claim that a) wetlands are a large and significant sink for carbon, and b) they are “rapidly diminishing”.

So what does the Bern model say about that?

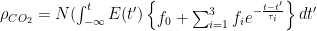

Y’know, it’s hard to figure out what the Bern model says about anything. This is because, as far as I can see, the Bern model proposes an impossibility. It says that the CO2 in the air is somehow partitioned, and that the different partitions are sequestered at different rates. The details of the model are given here.

For example, in the IPCC Second Assessment Report (SAR), the atmospheric CO2 was divided into six partitions, containing respectively 14%, 13%, 19%, 25%, 21%, and 8% of the atmospheric CO2.

Each of these partitions is said to decay at different rates given by a characteristic time constant “tau” in years. (See Appendix for definitions). The first partition is said to be sequestered immediately. For the SAR, the “tau” time constant values for the five other partitions were taken to be 371.6 years, 55.7 years, 17.01 years, 4.16 years, and 1.33 years respectively.

Now let me stop here to discuss, not the numbers, but the underlying concept. The part of the Bern model that I’ve never understood is, what is the physical mechanism that is partitioning the CO2 so that some of it is sequestered quickly, and some is sequestered slowly?

I don’t get how that is supposed to work. The reference given above says:

CO2 concentration approximation

The CO2 concentration is approximated by a sum of exponentially decaying functions, one for each fraction of the additional concentrations, which should reflect the time scales of different sinks.

So theoretically, the different time constants (ranging from 371.6 years down to 1.33 years) are supposed to represent the different sinks. Here’s a graphic showing those sinks, along with approximations of the storage in each of the sinks as well as the fluxes in and out of the sinks:

Now, I understand that some of those sinks will operate quite quickly, and some will operate much more slowly.

But the Bern model reminds me of the old joke about the thermos bottle (Dewar flask), that poses this question:

The thermos bottle keeps cold things cold, and hot things hot … but how does it know the difference?

So my question is, how do the sinks know the difference? Why don’t the fast-acting sinks just soak up the excess CO2, leaving nothing for the long-term, slow-acting sinks? I mean, if some 13% of the CO2 excess is supposed to hang around in the atmosphere for 371.3 years … how do the fast-acting sinks know to not just absorb it before the slow sinks get to it?

Anyhow, that’s my problem with the Bern model—I can’t figure out how it is supposed to work physically.

Finally, note that there is no experimental evidence that will allow us to distinguish between plain old exponential decay (which is what I would expect) and the complexities of the Bern model. We simply don’t have enough years of accurate data to distinguish between the two.

Nor do we have any kind of evidence to distinguish between the various sets of parameters used in the Bern Model. As I mentioned above, in the IPCC SAR they used five time constants ranging from 1.33 years to 371.6 years (gotta love the accuracy, to six-tenths of a year).

But in the IPCC Third Assessment Report (TAR), they used only three constants, and those ranged from 2.57 years to 171 years.

However, there is nothing that I know of that allows us to establish any of those numbers. Once again, it seems to me that the authors are just picking parameters.

So … does anyone understand how 13% of the atmospheric CO2 is supposed to hang around for 371.6 years without being sequestered by the faster sinks?

All ideas welcome, I have no answers at all for this one. I’ll return to the observational evidence regarding the question of whether the global CO2 sinks are “rapidly diminishing”, and how I calculate the e-folding time of CO2 in a future post.

Best to all,

w.

APPENDIX: Many people confuse two ideas, the residence time of CO2, and the “e-folding time” of a pulse of CO2 emitted to the atmosphere.

The residence time is how long a typical CO2 molecule stays in the atmosphere. We can get an approximate answer from Figure 2. If the atmosphere contains 750 gigatonnes of carbon (GtC), and about 220 GtC are added each year (and removed each year), then the average residence time of a molecule of carbon is something on the order of four years. Of course those numbers are only approximations, but that’s the order of magnitude.

The “e-folding time” of a pulse, on the other hand, which they call “tau” or the time constant, is how long it would take for the atmospheric CO2 levels to drop to 1/e (37%) of the atmospheric CO2 level after the addition of a pulse of CO2. It’s like the “half-life”, the time it takes for something radioactive to decay to half its original value. The e-folding time is what the Bern Model is supposed to calculate. The IPCC, using the Bern Model, says that the e-folding time ranges from 50 to 200 years.

On the other hand, assuming normal exponential decay, I calculate the e-folding time to be about 35 years or so based on the evolution of the atmospheric concentration given the known rates of emission of CO2. Again, this is perforce an approximation because few of the numbers involved in the calculation are known to high accuracy. However, my calculations are generally confirmed by those of Mark Jacobson as published here in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

Discover more from Watts Up With That?

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Quinn the Eskimo says:

May 8, 2012 at 10:43 am

Gail Combs –

You may also want to consider Glassman’s post and the Q & A that follows “On why CO2 is known not to have accumulated in the atmosphere & what is happening with CO2 in the modern era.” Very thorough discussion.

http://www.rocketscientistsjournal.com/2007/06/on_why_co2_is_known_not_to_hav.html#more

____________________________________

OH wonderful!

It is so nice to see someone has done a really good rebuttal on the well mixed conjecture. That is a really big nail in the coffin of CO2 warming hype.

BernieH says:

May 9, 2012 at 3:31 pm

Thanks, Bernie. If all of the R/C pairs are in parallel, then your circuit looks like this:

If it’s like that, the quickest path to ground is what rules. Since the claim in the Bern model is that the exponential decay is partitioned, it has to be a series circuit.

w.

Gail Combs says:

May 9, 2012 at 4:18 pm (Edit)

No, Gail and Quinn, it’s not wonderful at all. It’s wildly incorrect. The author of the article is conflating residence time with e-folding time (or half-life). He doesn’t know the difference between the two. As a result, his conclusions are totally incorrect. Re-read my Appendix above.

Finally, is CO2 well-mixed? Well, I suppose it depends on what you call “well-mixed”.

Note that everywhere but the south pole the range is from about 375 – 382 ppmv, or ± 1% … in my book, that’s well mixed. Include the south pole and the range goes to about 368 – 382 ppmv … that’s ± 2%. Again, I call that well-mixed.

In other words, the citation is not a nail in the coffin of anyone but the author.

w.

No, I would use it to begin looking at the change in CO2 concentration with respect to average wind speed and direction with respect to changes in

1. Surface temperature (Cold Japanese current, hotter far west deserts and great basin, slightly cooler eastern US), hotter Gulf Stream off of east coast, colder currents off of Europe, then the central Asian barren highlands and back over the (colder and warmer) Pacific currents.

2. surface mass of growing plants: Great basin across Great plains to farmed Midwest to very tree-covered east coast), then barren areas in central Asia to the very overgrown Indian Peninsula …

3. Lower levels over the Amazon – that extend out over the Atlantic Ocean. But these conflict with the barren Saudi peninsula and Afghanistan and Mongolia that don’t match vegetation, and don’t match human activity to the immediate west. Odd.

4. Amount of human released CO2.

5. Actual direction and speeds of the “average” wind WHEN the measurements of the CO2 were taken.

Highest areas don’t “seem” to track with industrial activity (great basin, mountainous west, but then a high spot over the Atlantic Ocean. If you “translate human activity east” (assuming some west-to-east wind pattern), then where did Europe’s CO2 go? Where did Saudi Arabia and Afghanistan’s CO2 come from? Why is the CO2 high over the entire mountain area out west? There’s nobody west of there other than islands of people at LA and SFO. And nobody west of them for thousands of miles.

Applause, Thank you all for a very interesting discussion !

Hi Willis

What I am doing is less ambitious than what you and others here seem to be attempting.

I am (in the back of my mind) thinking about how CO2 in the atmosphere moves in, out, and about, but I am only working with the

mathematics in the link as what it is – a simple RC network. The integral equation given there is a fundamental convolution relationship between an input signal and the impulse response of a system. Just sophomore-level Laplace transform system theory – no big deal to an EE.

The equation describes the relationship between E (the input) and rho (the concentration). It seems to me that E is an extensive variable (an “amount” or quantity) while rho is an intensive variable (a property, a characteristic number, a concentration, in the same units as C) so we don’t seem to be talking about transfer of anything (such as electrons or CO2 molecules) but only a numerical ratio. So my RC network is a computational device only – it does not represent physical reality.

This “computer” happens to be composed of resistors, capacitors, buffer/multipliers, and a summer. I don’t know how to put a picture in comments here, so I have posted the schematic diagram at:

http://electronotes.netfirms.com/BernModelRC.jpg

Aside from scaling factors (which I would probably get wrong!), the diagram there is the one and only RC network that corresponds to the impulse response in the [ ]. The input is an “inventory” number of all CO2 going in, and rho is a number some “master controller” of all sinks is instructed to maintain. The sinks are NOT a physical analog of the electrons flows in the network – as least as their mathematics shows it.

Much as you and others here have problems with the partitions, so do I. I am not, but if I were considering a true electrical analog (electrons = CO2 molecules and capacitors represent storage of CO2) there is only one atmosphere (one capacitor) and one grand summed source (E) and one net sink. That would be one net resistor – if it’s even linear.

I think they were facing the problem that there does not seem to be a simple (one) exponential decay. Parallel RC’s is one way of handling this (Kautz functions are better). But the parallel RC suggests the partitioning. That’s a problem. Perhaps it was just intended as a computer, not as a physical model.

http://wattsupwiththat.com/2012/05/06/the-bern-model-puzzle/#comment-980201

richardscourtney says: May 9, 2012 at 1:34 am

Allan MacRae asks;

“I am trying to find references to a major misalignment between the ice core CO2 record and modern atmospheric records of CO2, one that was allegedly “solved” by shifting the ice core record until it matched the modern record. Can anyone help please?”

Richard: The earliest explanation of the ‘need’ to adjust the data I know of is in

Siegenthaler U & Oeschger H, ‘Biospheric CO2 emissions during the last 200 years reconstructed by deconvolution of ice core data’, Tellus 39B; 14-154 (1987)

In that paper S&O assert that ice closure time means the data needs to be offset by decades of time because the ‘trapped’ air indicates the atmospheric composition at time of closure. And S&O assert the required offset is indicated by adjusting the data to overlay with the Mauna Loa data.

The earliest paper I know of which adjusts ice core data according to the S&O assertion is

Etheridge DM, Pearman GI & de Silva F, ‘Atmospheric trace-gas variations as revealed by air trapped in an ice core from Law Dome, Antarctica’, Ann. Glaciol. , 10; 28-33 (1988)

(The S&O assertion is clearly daft: there is no known mechanism that would move all the air up through the firn a distance that equates to decades of elapsed time. Indeed, basic physics says atmospheric pressure variations would mix the gases at different elevations while diffusion would tend to reduce high concentrations and increase low concentrations until the ice closed.)

Richard

*********

Thank you very much Richard – I hope you are well. Yes, that is exactly what I was seeking.

Note to Richard, Bart, Willis and others:

This shifting of ice core data to align with Mauna Loa data is just one of several examples of confirmation bias in the current hypothesis that CO2 MUST drive temperature, and the related hypothesis that the primary source of increasing atmospheric CO2 MUST BE humankind.

When one starts to examine this complex subject, similar contradictions become apparent, not the least of which is that atmospheric CO2 lags temperature at all measured time scales (and dCO2/dt changes ~contemporaneously with temperature).

The counterarguments for the observed ~9 month lag of CO2 after temperature are:

A. It is a “feedback effect”.

B. It is clear evidence that time machines really do exist.

Both counterarguments A and B are supported by equally compelling evidence. 🙂

To me, one must start with the evidence, and work back to a logical hypothesis. The CO2-drives-temperature hypothesis and related man-drives-CO2 hypothesis both start with the hypo, and then try (unsuccessfully, imo) to fit the evidence to the hypo. When the evidence fails to fit, the data is “adjusted” and yet another illogical hypo (move-the-air–up-the-ice-firn) is invented, and so on, and so on. The alleged physical system becomes increasingly Byzantine, and increasingly improbable. That, I submit, is the current highly improbable state of “settled” climate science.

I would prefer to start with the evidence, as stated above, and then try to respect fundamental logical concepts such as the Uniformitarian Principle and Occam’s Razor.

Here are some thoughts:

In 2008, I wrote that atmospheric CO2 lagged atmospheric temperature T by ~9 months on a short-time-cycle (~3- 4 years – between major El Nino’s?).

http://icecap.us/images/uploads/CO2vsTMacRae.pdf

I also noted that CO2 lags temperature by ~800 years from ice core data, on a much longer temperature-time cycle..

I have suggested that there could be one or more intermediate cycles where CO2 lags temperature (between 9 months and 800 years).

There should be ample evidence in existing data to develop a much more credible and simpler hypothesis that does not rely for support on data-shifting, “feedback effects” and many other improbable hypotheses.

Regards, Allan

Summary – Multiple Cycles in which CO2 Lags Temperature:

For a mechanism, see Veizer (2005).

I think there are perhaps four cycles in which CO2 lags T:

1. A cycle of thousands of years, in which CO2 lags T by ~~800 years (Vostok ice cores, etc.)

2. A cycle of ~70-90 years (Gleissberg, PDO or similar), in which CO2 lags T by ~5-10 years. This “Beck hypo” is highly contentious – the late Ernst Beck’s direct-measurement CO2 data allegedly supports this possibility, and there is the important question of how much humanmade CO2 affects this and subsequent cycles. Ernst Beck was widely disrespected and his work dismissed by both sides of the CAGW debate – I think this was most unfortunate, and probably was an intellectual and ethical error – there is possibly some merit, particularly in Beck’s data collection work, and many were too quick to dismiss it.

3. The cycle I described in my 2008 icecap.us paper of 3-5 years (El Nino/La Nina), in which CO2 lags T by ~9 months.

4. The seasonal “sawtooth” CO2 cycle, which ranges from ~18 ppm in the North to ~1 ppm at the South Pole.

It is clear that T precedes CO2 in cycles 1, 3 and 4. For possible Cycle 2 we may have inadequate data.

– Allan MacRae, circa 2008

Friends:

OK, it is time to be clear.

The carbon cycle cannot be represented by a ‘plumbing’ or ‘electrical’ circuit because all the ‘tanks’ or ‘resistors’ change with time and their magnitudes, variations and connections are almost completely unknown . Also, the real-world system is very complicated.

The magnitude of the problem is obvious when the processes of the carbon cycle (i.e. the ‘tanks’ or ‘electrical resistors’ and their connections) are considered.

In our paper that I reference above, we considered the most important processes in the carbon cycle to be:

Short-term processes

1. Consumption of CO2 by photosynthesis that takes place in green plants on land. CO2 from the air and water from the soil are coupled to form carbohydrates. Oxygen is liberated. This process takes place mostly in spring and summer. A rough distinction can be made:

1a. The formation of leaves that are short lived (less than a year).

1b. The formation of tree branches and trunks, that are long lived (decades).

2. Production of CO2 by the metabolism of animals, and by the decomposition of vegetable matter by micro-organisms including those in the intestines of animals, whereby oxygen is consumed and water and CO2 (and some carbon monoxide and methane that will eventually be oxidised to CO2) are liberated. Again distinctions can be made:

2a. The decomposition of leaves, that takes place in autumn and continues well into the next winter, spring and summer.

2b. The decomposition of branches, trunks, etc. that typically has a delay of some decades after their formation.

2c. The metabolism of animals that goes on throughout the year.

3. Consumption of CO2 by absorption in cold ocean waters. Part of this is consumed by marine vegetation through photosynthesis.

4. Production of CO2 by desorption from warm ocean waters. Part of this may be the result of decomposition of organic debris.

5. Circulation of ocean waters from warm to cold zones, and vice versa, thus promoting processes 3 and 4.

Longer-term process

6. Formation of peat from dead leaves and branches (eventually leading to lignite and coal).

7. Erosion of silicate rocks, whereby carbonates are formed and silica is liberated.

8. Precipitation of calcium carbonate in the ocean, that sinks to the bottom, together with formation of corals and shells.

Natural processes that add CO2 to the system:

9. Production of CO2 from volcanoes (by eruption and gas leakage).

10. Natural forest fires, coal seam fires and peat fires.

Anthropogenic processes that add CO2 to the system:

11. Production of CO2 by burning of vegetation (“biomass”).

12. Production of CO2 by burning of fossil fuels (and by lime kilns).

Several of these processes are rate dependant and several of them interact.

At higher air temperatures, the rates of processes 1, 2, 4 and 5 will increase and the rate of process 3 will decrease. Process 1 is strongly dependent on temperature, so its rate will vary strongly (maybe by a factor of 10) throughout the changing seasons.

The rates of processes 1, 3 and 4 are dependent on the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere. The rates of processes 1 and 3 will increase with higher CO2 concentration, but the rate of process 4 will decrease.

The rate of process 1 has a complicated dependence on the atmospheric CO2 concentration. At higher concentrations at first there will be an increase that will probably be less than linear (with an “order” <1). But after some time, when more vegetation (more biomass) has been formed, the capacity for photosynthesis will have increased, resulting in a progressive increase of the consumption rate.

Processes 1 to 5 are obviously coupled by mass balances. Our paper assessed the steady-state situation to be an oversimplification because there are two factors that will never be “steady”:

I. The removal of CO2 from the system, or its addition to the system.

II. External factors that are not constant and may influence the process rates, such as varying solar activity.

Modeling this system is a difficult because so little is known concerning the rate equations. However, some things can be stated from the empirical data.

At present the yearly increase of the anthropogenic emissions is conservatively about 0.1 GtC/year. The natural fluctuation of the excess consumption (i.e. consumption processes 1 and 3 minus production processes 2 and 4) is at least 6 ppmv (which corresponds to 12 GtC) in 4 months. This is more than 100 times the yearly increase of human production, which strongly suggests that the dynamics of the natural processes here listed 1-5 can cope easily with the human production of CO2. A serious disruption of the system may be expected when the rate of increase of the anthropogenic emissions becomes larger than the natural variations of CO2. But the above data indicates this is not possible.

The accumulation rate of CO2 in the atmosphere (1.5 ppmv/year which corresponds to 3 GtC/year) is equal to almost half the human emission (6.5 GtC/year). However, this does not mean that half the human emission accumulates in the atmosphere, as is often stated. There are several other and much larger CO2 flows in and out of the atmosphere. The total CO2 flow into the atmosphere is at least 156.5 GtC/year with 150 GtC/year of this being from natural origin and 6.5 GtC/year from human origin. So, on the average, 3/156.5 = 2% of all emissions “accumulate” in the air.

And there are people who think they can make a meaningful simple model of that when nobody knows the rate constants of any of the processes!

Richard

Hi Willis, . A current

. A current  is charging it. As it charges, the charge is shared with three other capacitors, labelled

is charging it. As it charges, the charge is shared with three other capacitors, labelled  through resistors that limit the current. a is atmosphere, s is sea surface layer, m is the middle ocean beneath that and d is the deep ocean bottom (only), but of course one could add soil, leaf water, and so on. Note well that equilibrium depends on the sizes of the capacitances (relative to

through resistors that limit the current. a is atmosphere, s is sea surface layer, m is the middle ocean beneath that and d is the deep ocean bottom (only), but of course one could add soil, leaf water, and so on. Note well that equilibrium depends on the sizes of the capacitances (relative to  ) and the resistances.

) and the resistances. dumps e.g. a bolus of charge on

dumps e.g. a bolus of charge on  . It bleeds through the surface resistance

. It bleeds through the surface resistance  to try to equilibrate the potential differences across

to try to equilibrate the potential differences across  and

and  , but as it does so some of the charge is similarly bled off

, but as it does so some of the charge is similarly bled off  through resistance

through resistance  onto

onto  .

. remains in the system, shared between $C_a, C_s, C_m$. How much remains in $C_a$ depends on the relative magnitudes of the other two — in particular, if

remains in the system, shared between $C_a, C_s, C_m$. How much remains in $C_a$ depends on the relative magnitudes of the other two — in particular, if  , then less than 1.7 % of the total surplus charge will end up on

, then less than 1.7 % of the total surplus charge will end up on  because the ratio of

because the ratio of  must be the same for all three capacitors.

must be the same for all three capacitors. is “infinite” in size. It is then formally equivalent to ground — indeed the Earth itself IS an enormous capacitor that acts as a ground. If indeed what I label the deep ocean is ground, capable of “permanently” sequestering CO_2 for periods of tens to hundreds of millions of years, requiring an actual turnover of the crust to return it back to the atmosphere, or if it is simply a vast reservoir compared to even

is “infinite” in size. It is then formally equivalent to ground — indeed the Earth itself IS an enormous capacitor that acts as a ground. If indeed what I label the deep ocean is ground, capable of “permanently” sequestering CO_2 for periods of tens to hundreds of millions of years, requiring an actual turnover of the crust to return it back to the atmosphere, or if it is simply a vast reservoir compared to even  that can hold almost as much carbon as you drop into it without significantly altering the CO_2/charge in

that can hold almost as much carbon as you drop into it without significantly altering the CO_2/charge in  , we can just put a resistor between any reservoir that can directly dump carbon there in our circuit above.

, we can just put a resistor between any reservoir that can directly dump carbon there in our circuit above. in the figure above with a switch, so one can mentally understand what happens when the switch is closed. Without the pathway (switch open), CO_2/charge builds up indefinitely as there is a nonzero current

in the figure above with a switch, so one can mentally understand what happens when the switch is closed. Without the pathway (switch open), CO_2/charge builds up indefinitely as there is a nonzero current  into the atmosphere

into the atmosphere  with nowhere to ultimately go to ground. With the switch closed, things are very different indeed. Now charge constantly bleeds off of all three capacitors to ground. The only way to sustain the CO_2 levels in all three is via a nonzero current

with nowhere to ultimately go to ground. With the switch closed, things are very different indeed. Now charge constantly bleeds off of all three capacitors to ground. The only way to sustain the CO_2 levels in all three is via a nonzero current  .

. can remain in equilibrium with a nonzero non-anthropogenic current so that only anthropogenic current counts as “charge” in

can remain in equilibrium with a nonzero non-anthropogenic current so that only anthropogenic current counts as “charge” in  . There are many known non-anthropogenic currents (sources of CO_2) and without a path to either “ground” or a very large reservoir any nonzero current will monotonically boost the charge/CO_2 content of

. There are many known non-anthropogenic currents (sources of CO_2) and without a path to either “ground” or a very large reservoir any nonzero current will monotonically boost the charge/CO_2 content of  .

. is already more than capable of “grounding”

is already more than capable of “grounding”  as far as the current discussion is concerned — the ocean contains many, many times more CO_2 in chemical equilibrium than the atmosphere contains, and the “fraction” of any addition that should be permanent in the atmosphere is strictly less than the ratio of their capacitances, all things being equal. So the 0.15 factor in the Bern equation makes little sense to me on strictly physical grounds. If the equilibrium atmosphere contained 15% of all of the carbon in the carbon cycle, that would be the right number. It doesn’t, and it isn’t.

as far as the current discussion is concerned — the ocean contains many, many times more CO_2 in chemical equilibrium than the atmosphere contains, and the “fraction” of any addition that should be permanent in the atmosphere is strictly less than the ratio of their capacitances, all things being equal. So the 0.15 factor in the Bern equation makes little sense to me on strictly physical grounds. If the equilibrium atmosphere contained 15% of all of the carbon in the carbon cycle, that would be the right number. It doesn’t, and it isn’t.

I have to say that I don’t like your RC circuit diagram — you need to put the “atmosphere” in parallel, not in series, and it isn’t really a parallel circuit anyway. Also, you don’t need two resistors in the circuit on either side of the capacitors — one will do since resistors in series add anyway.

I have no way to add a jpg graphic (that I know of) to this — I’ll try doing it in raw html pointing to images I just put onto my own web space, but if Mr. Moderator or anyone with cool super powers can download them and put them inline I would appreciate it.

This is what you were trying to construct, I think. It shows the atmosphere as a capacitor

However, this model is not correct. The atmosphere doesn’t share CO_2 (“charge”) with the deep ocean or middle ocean directly and the rates from surface to middle depend on the differences in “voltage” across the surface capacitor relative to middle, not atmosphere to middle. The first metaphor might work to find equilibrium, when there is no current flowing and the potentials across all the capacitors must be the same, but it won’t work to describe the APPROACH to equilibrium correctly.

I offer a slightly alternative model:

A current

At this point there is no path to ground. All the charge you put in via

Suppose, however, that

I drew such a resistive pathway

I do not suggest that this is an accurate model for the atmosphere, but it is one that at least roughly corresponds to the three processes outlined in the set of coupled ODEs above. Personally, I found the “rocket science journal” discussion of the surface equilibrium exchange a lot more reasonable — it doesn’t try to pretend that

Even

rgb

Figures ADDED by Anthony at the request of RGB:

http://www.phy.duke.edu/~rgb/rc-model.jpg

http://www.phy.duke.edu/~rgb/rc-model2.jpg

OK, it is time to be clear.

The carbon cycle cannot be represented by a ‘plumbing’ or ‘electrical’ circuit because all the ‘tanks’ or ‘resistors’ change with time and their magnitudes, variations and connections are almost completely unknown . Also, the real-world system is very complicated.

Agreed. Please note that I was only correcting Willis’ effort because series was so obviously wrong. In series all of the carbon placed on the lead capacitor just stays there.

However, it actually CAN be so represented. What you are saying is we don’t know how to set the values, and, as you also say, the representation can be wrong. Both are quite true.

I’m reading my way through “The Black Swan”. It should (IMO) be required reading for all scientists. It graphically and precisely illustrates the risk of naive mathematical models, especially those that we have “reduced” to have only a few parameters (usually because that’s all our Platonic little minds can wrap themselves around). It also thoroughly explores the human tendency towards confirmation bias, because we stubbornly continue to try to confirm a theory (which is impossible, usually) instead of disprove it (which is easy, when it works). Feynman says much the same thing — the sad thing about modern science is that we don’t publish null results, and our brains get dopamine-driven satisfaction from “being right”. It is very difficult to say “I don’t know”, or “my favorite hypothesis, when compared to the data, doesn’t quite work right”.

rgb

Any chance (Mr. Moderator) of inserting the figures?

Here they are:

http://www.phy.duke.edu/~rgb/rc-model.jpg

http://www.phy.duke.edu/~rgb/rc-model2.jpg

for those that are wondering why my post above refers to figures and there aren’t any figures.

rgb

REPLY: Done, Anthony

rgbatduke:

At May 10, 2012 at 8:43 am you say to me;

“Please note that I was only correcting Willis’ effort because series was so obviously wrong. In series all of the carbon placed on the lead capacitor just stays there.

However, it actually CAN be so represented. What you are saying is we don’t know how to set the values, and, as you also say, the representation can be wrong. Both are quite true.”

Yes, I knew you were “only correcting Willis’ effort”, and I write to confirm that your understanding of my point is exactly right.

I take this opportunity to thank you for your excellent contributions to the above discussion. I value them.

Richard

richardscourtney says:

May 10, 2012 at 10:19 am

Yeah, as usual Robert Brown has it right … teach me to post late at night without thinking …

w.

richardscourtney says:

May 10, 2012 at 4:32 am

“The carbon cycle cannot be represented by a ‘plumbing’ or ‘electrical’ circuit because all the ‘tanks’ or ‘resistors’ change with time and their magnitudes, variations and connections are almost completely unknown .”

Yes. Which is why I have been saying the value of these models, IMHO, is substantially qualitative.

It is easy to get wrapped around the axle looking at ever more intricate models but, at some point, you gain more insight by stepping back and viewing the forest rather than the trees.

In the model I proffered here, I subsumed all the complexity by allowing the time constant and gains to be operator theoretic. Bounding behavior of the system can be obtained by making these operators constant equal to infinity normed values. It is then apparent that the fundamental properties of the real world system are 1) relatively rapid sequestration of inputs (large norm of the inverse time constant) and 2) temperature sensitivity of sufficient magnitude such that temperature is driving the output.

Aside: Regarding electrical circuit analogies, the case of transmission lines is instructive. These are modeled using parameters such as conductance and capacitance per unit length. Under appropriate circumstances, a distributed element model of discrete components can be used to approximate the behavior. How well the model approximates the true behavior depends on the length of the line, the bandwidth of the signals to which the line will be subjected, and the source and load impedances (boundary conditions). A precise model would be inifinite dimensional, but the number of lumped parameters can be truncated in order to achieve a given degree of fidelity. You generally can get these types of models when you deal with continuum systems which are governed by partial differential equations.

Bart:

Thankyou for your post at May 10, 2012 at 10:39 am.

Before saying why I am responding to your post, I remind of my position which I have stated in many places including WUWT; viz.

I don’t know what has caused the recent rise in atmospheric CO2 concentration, but I want to know.

So, being aware of my stated position, you will surely understand my two responses to your post that I am replying.

Firstly, I thank you for reminding of the simple empirical model which you provided at May 7, 2012 at 10:50 am above. My problem with it is that it fits to a short time series (i.e. 1958 to present) and I fail to see the value of that because – in the absence of a physical basis – extrapolating any such fit is a ‘risky’ thing to do. However, I agree with its assessment that (in the existing data) temperature change is the observable dominant effect on atmospheric CO2; indeed, I have said that in this thread, too.

Secondly, and more importantly, I am very interested in your suggestion that a distributed element model may be helpful to understanding the system. Please note that my background is in materials science so I am very familiar with systems analyses, but I have no knowledge of electrical engineering and, therefore, I am ignorant of distributed element models (i.e. I don’t know what they are, what they do, what they can’t do, and what insights they may provide).

Hence, I write to request an expansion of your suggestion that a distributed element model may be helpful to understanding the system of the carbon cycle. And I ask you to remember my ignorance of electrical engineering so I need an explanation which I can understand (if that is possible).

Richard

Hi RGB –

I am not sure what I(t) in your model2.jpg (which I like fairly well) is exactly. It does not seem to be the “bolus” of CO2 you mention or you would be talking impulse response of the network (which would be a perfectly good way to analyze it). Neither do I think it is merely the current that happens to be flowing in from some other attached driver. So I take it to be an actual “current source” in the sense EE’s us the term.

Try walking into your local Radio Shack and asking for a “current source”. They have only batteries – voltage sources. For anyone this bothers, a good idea of a current source would be a battery with an absurdly large series resistance (say a 1.5 volt battery and 1000 megohms series, which delivers 1.5 na to any ordinary load).

Now, there is of course no switch, so let’s assume our current source is attached, and that it is a constant current Io. Ca begins to charge, and in turn, Cs and Cm, with Rd beginning to draw off current. As you point out, Ca no longer ramps without limit.

I make it that the voltage on Ca becomes Va = Io(Rs+Rd). That is, Io eventually spills through the Rs and Rd series. So Cs becomes charged to Vs=VaRd/(Rs+Rd). And Cm has a voltage Vm = Vs, since no current flows through Rm. This would make Cs and Cm all one “sea” which makes sense.

It would probably be worth looking at the impulse response and/or the decay from constant current charge. What do you think?

I am not sure what I(t) in your model2.jpg (which I like fairly well) is exactly. It does not seem to be the “bolus” of CO2 you mention or you would be talking impulse response of the network (which would be a perfectly good way to analyze it). Neither do I think it is merely the current that happens to be flowing in from some other attached driver. So I take it to be an actual “current source” in the sense EE’s us the term.

. Lots of trunk wiggling room.

. Lots of trunk wiggling room. — the charge on a capacitor — is the moral equivalent of

— the charge on a capacitor — is the moral equivalent of  (or more correctly, its volume integral, the total CO_2 in the atmosphere). E(t) in the Bern equation is the “anthropogenic CO_2 current” that is charging up the atmospheric capacitance, which then “drains” at exponential rates $R = 1/\tau$ into reservoirs 1, 2 and 3.

(or more correctly, its volume integral, the total CO_2 in the atmosphere). E(t) in the Bern equation is the “anthropogenic CO_2 current” that is charging up the atmospheric capacitance, which then “drains” at exponential rates $R = 1/\tau$ into reservoirs 1, 2 and 3. , not

, not  as it is given in the Bern formula. This does depend on the time constants of the various reservoirs, of course.

as it is given in the Bern formula. This does depend on the time constants of the various reservoirs, of course.

I’m assuming it to play precisely the same role as “E(t)” in the Bern equation:

Note the eight parameters:

The point of the metaphor is that

This doesn’t make complete sense to me. It is claimed that the reason for the three terms is (ultimately) detailed balance between three reservoirs and the atmospheric reservoir, perturbing a pre-existing equilibrium with the additional CO_2. In a word, as with the first capacitive model above, any additional CO_2 “charge” delivered to the atmosphere is shared across all connected reservoirs until they all have balanced rates of exchange.

However, it is perfectly obvious that when that is true, the different reservoirs will share the CO_2 in — certainly to first order — the same proportion that they already share it in equilibrium. That is, one would expect roughly 50 parts of any surplus to end up in the ocean (which contains roughly 50 times as much carbon as the air). In the end, that means

But all of this is highly idealized. As Richard Courtney and Bart have pointed out, things are a lot more complicated and unknown than this. For example, every one of the capacitors in the simplified model have variable capacitance and time constants. They vary with respect to many coupled parameters. For example, thinking only of the surface (euphotic zone), things that affect absorption rates include: temperature, wind speed over the surface, frothiness of the surface (related to wind speed), local carbon dioxide content, local nutrient content (oceanic phytoplankton are often growth limited by other nutrients than CO_2), carbon dioxide content above the surface in the atmosphere, presence/absence of sunlight, and details of the thermohaline circulation. Many of these factors are thus themselves functions of both location and past history! — average functions of location, as waters up in Nova Scotia are always a lot colder than they are around Puerto Rico and very likely experience quite different average sustained wind speeds and have different nutrient content and biology. Past history is more complicated — thermohaline circulation operates on a dazzling array of timescales, the longest of which (for complete turnover) are around 1000 years.

That means that the carbon dioxide content of deep oceanic water welling up to the surface — which in part determines how much that water is happy absorbing or releasing once it gets there — was laid down as long as 1000 years ago. It also means that there is a possibility of resonant amplification and positive feedback on an (order of) thousand year loop or any of several shorter loop times in between as thermohaline circulation is chaotic and complex and not just a single coherent flow. Global decadal atmospheric oscillations no doubt play a role as well.

In the end, this means (as Bart suggests, I think) that atmospheric CO_2 content is regulated far more strongly by variations in the capacitance of the soils and the sea than it is by the human “current”.

rgb

[Latex fixed, although you should check it, it seems to be missing a close parenthesis. For the large braces, you need to use \begin{Bmatrix} and \end{Bmatrix}. For large brackets, use \begin{bmatrix} and \end{bmatrix} … w.]

Damn, and I checked it. Likely the wordpress latex doesn’t like \left{ \right} pairs or the like. Sigh. Help Mr. Moderator? I’m really sorry…

rgb

Think rgb meant this:

( Dr. Brown, your were just missing the final “\right}” )

Mods, I’m sorry too. The correct Latex is here. rgb is correct, it was the \left{ or \right} though Latex editors accept it fine. We learn.

http://wattsupwiththat.com/test-2/#comment-982254

[Wayne, see my note above regarding the use of “\begin{Bmatrix}” and “\end{Bmatrix}. w.]

Excerpts from Veizer (GAC 2005):

Pages 14-15: The postulated causation sequence is therefore: brighter sun => enhanced thermal flux + solar wind => muted CRF => less low-level clouds => lower albedo => warmer climate.

Pages 21-22: The hydrologic cycle, in turn, provides us with our climate, including its temperature component. On land, sunlight, temperature, and concomitant availability of water are the dominant controls of biological activity and thus of the rate of photosynthesis and respiration. In the oceans, the rise in temperature results in release of CO2 into air. These two processes together increase the flux of CO2 into the atmosphere. If only short time scales are considered, such a sequence of events would be essentially opposite to that of the IPCC scenario, which drives the models from the bottom up, by assuming that CO2 is the principal climate driver and that variations in celestial input are of subordinate or negligible impact….

… The atmosphere today contains ~ 730 PgC (1 PgC = 1015 g of carbon) as CO2 (Fig. 19). Gross primary productivity (GPP) on land, and the complementary respiration flux of opposite sign, each account annually for ~ 120 Pg. The air/sea exchange flux, in part biologically mediated, accounts for an additional ~90 Pg per year. Biological processes are therefore clearly the most important controls of atmospheric CO2 levels, with an equivalent of the entire atmospheric CO2 budget absorbed and released by the biosphere every few years. The terrestrial biosphere thus appears to have been the dominant interactive reservoir, at least on the annual to decadal time scales, with oceans likely taking over on centennial to millennial time scales.

richardscourtney says:

May 10, 2012 at 11:39 am

“My problem with it is that it fits to a short time series (i.e. 1958 to present) and I fail to see the value of that because…”

It’s 54 years. And, it’s the only reliable data we have.

“Hence, I write to request an expansion of your suggestion that a distributed element model may be helpful to understanding the system of the carbon cycle. “

It was merely an attempt on my part to point out that lumped parameter models, such as in rgbatduke @ur momisugly May 10, 2012 at 8:32 am, are generally approximations to a continuum model with is defined by partial differential equations.

Again, my main point is that we do not need to wade so deeply into models which cannot be authenticated with present data. It is clear that the broad general outline of the system is that, here and now, and for the past several decades, sinks are more active than supposed so that the sequestration feedback is strong, which attenuates the anthropogenic input markedly, and sensitivity to temperature is high. These conclusions fly directly in the face of the assumption that atmospheric CO2 concentration is being driven by humans.

rgbatduke says:

May 11, 2012 at 3:26 am

‘In the end, this means (as Bart suggests, I think) that atmospheric CO_2 content is regulated far more strongly by variations in the capacitance of the soils and the sea than it is by the human “current”.’

Indeed, he does. More than suggests. Asserts with evidence, that being that the atmospheric CO2 concentration has tracked the integrated temperature anomaly with respect to a particular baseline for the past 54 years, and assuredly into the next several at the very least.

“…for the past 54 years, and assuredly into the next several at the very least.”

I meant my statement to be more forceful than that. I had it in my head that I had described the interval as “decades”. The relationship will almost assuredly hold for the next several decades at the very least.