Guest Post by Willis Eschenbach

I was reading through the recent Trenberth paper on ocean heat content that’s been discussed at various locations around the web. It’s called “Distinctive climate signals in reanalysis of global ocean heat content”, paywalled, of course. [UPDATE: my thanks to Nick Stokes for locating the paper here.] Among the “distinctive climate signals” that they claim to find are signals from the massive eruptions of Mt. Pinatubo in mid-1991 and El Chichon in mid-1982. They show these claimed signals in my Figure 1 below, which is also Figure 1 in their paper.

ORIGINAL CAPTION: Figure 1. OHC integrated from 0 to 300 m (grey), 700 m (blue), and total depth (violet) from ORAS4, as represented by its 5 ensemble members. The time series show monthly anomalies smoothed with a 12 month running mean, with respect to the 1958–1965 base period. Hatching extends over the range of the ensemble members and hence the spread gives a measure of the uncertainty as represented by ORAS4 (which does not cover all sources of uncertainty). The vertical colored bars indicate a two year interval following the volcanic eruptions with a 6 month lead (owing to the 12 month running mean), and the 1997–98 El Niño event again with 6 months on either side. On lower right, the linear slope for a set of global heating rates (W m-2) is given.

ORIGINAL CAPTION: Figure 1. OHC integrated from 0 to 300 m (grey), 700 m (blue), and total depth (violet) from ORAS4, as represented by its 5 ensemble members. The time series show monthly anomalies smoothed with a 12 month running mean, with respect to the 1958–1965 base period. Hatching extends over the range of the ensemble members and hence the spread gives a measure of the uncertainty as represented by ORAS4 (which does not cover all sources of uncertainty). The vertical colored bars indicate a two year interval following the volcanic eruptions with a 6 month lead (owing to the 12 month running mean), and the 1997–98 El Niño event again with 6 months on either side. On lower right, the linear slope for a set of global heating rates (W m-2) is given.

I looked at that and I said “Whaaa???”. I’d never seen any volcanic signals like that in the ocean heat content data. What was I missing?

Well, what I was missing is that Trenberth et al. are using what is laughably called “reanalysis data”. But as the title says, reanalysis “data” isn’t data in any sense of the word. It is the output of a computer climate model masquerading as data.

Now, the basic idea of a “reanalysis” is not a bad one. If you have data with “holes” in it, if you are missing information about certain times and/or places, you can use some kind of “best guess” algorithm to fill in the holes. In mining, this procedure is quite common. You have spotty data about what is happening underground. So you use a kriging procedure employing all the available information, and it gives you the best guess about what is happening in the “holes” where you have no data. (Please note, however, that if you claim the results of your kriging model are real observations, if you say that the outputs of the kriging process are “data”, you can be thrown in jail for misrepresentation … but I digress, that’s the real world and this is climate “science” at its finest.)

The problems arise as you start to use more and more complex procedures to fill in the holes in the data. Kriging is straight math, and it gives you error bars on the estimates. But a global climate model is a horrendously complex creature, and gives no estimate of error of any kind.

Now, as Steven Mosher is fond of pointing out, it’s all models. Even something as simple as

Force = Mass times Acceleration

is a model. So in that regard, Steven is right.

The problem is that there are models and there are models. Some models, like kriging, are both well-understood and well-behaved. We have analyzed and tested the model called “kriging”, to the point where we understand its strengths and weakness, and we can use it with complete confidence.

Then there is another class of models with very different characteristics. These are called “iterative” models. They differ from models like kriging or F = M A because at each time step, the previous output of the model is used as the new input for the model. Climate models are iterative models. In a climate model, for example, it starts with the present weather, and predicts where the weather will go at the next time step (typically a half hour).

Then that result, the prediction for a half hour from now, is taken as input to the climate model, and the next half-hour’s results are calculated. Do that about 9,000 times, and you’ve simulated a year of weather … lather, rinse, and repeat enough times, and voila! You now have predicted the weather, half-hour by half-hour, all the way to the year 2100.

There are two very, very large problems with iterative models. The first is that errors tend to accumulate. If you calculate one half hour even slightly incorrectly, the next half hour starts with bad data, so it may be even further out of line, and the next, and the next, until the model goes completely off the rails. Figure 2 shows a number of runs from the Climateprediction climate model …

Figure 2. Simulations from climateprediction.net. Note that a significant number of the model runs plunge well below ice age temperatures … bad model, no cookies!

Figure 2. Simulations from climateprediction.net. Note that a significant number of the model runs plunge well below ice age temperatures … bad model, no cookies!

See how many of the runs go completely off the rails and head off into a snowball earth, or take off for stratospheric temperatures? That’s the accumulated error problem in action.

The second problem with iterative models is that often we have no idea how the model got the answer. A climate model is so complex and is iterated so many times that the internal workings of the model are often totally opaque. As a result, suppose that we get three very different answers from three different runs. We have no way to say that one of them is more likely right than the other … except for the one tried and true method that is often used in climate science, viz:

If it fits our expectations, it is clearly a good, valid, solid gold model run. And if it doesn’t fit our expectations, obviously we can safely ignore it.

So how many “bad” reanalysis runs end up on the cutting room floor because the modeler didn’t like the outcome? Lots and lots, but how many nobody knows.

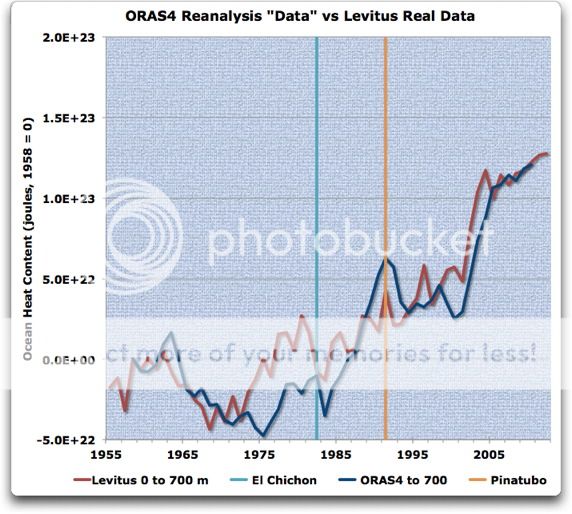

With that as a prelude, let’s look at Trenberth’s reanalysis “data”, which of course isn’t data at all … Figure 3 compares the ORAS4 reanalysis model results to the Levitus data:

Figure 3. ORAS4 reanalysis results for the 0-2000 metre layer (blue) versus Levitus data for the same layer. ORAS4 results are digitized from Figure 1. Note that the ORAS4 “data” prior to about 1980 has error bars from floor to ceiling, and so is of little use (see Figure 1). The data is aligned to their common start in 1958 (1958=0)

Figure 3. ORAS4 reanalysis results for the 0-2000 metre layer (blue) versus Levitus data for the same layer. ORAS4 results are digitized from Figure 1. Note that the ORAS4 “data” prior to about 1980 has error bars from floor to ceiling, and so is of little use (see Figure 1). The data is aligned to their common start in 1958 (1958=0)

In Figure 3, the shortcomings of the reanalysis model results are laid bare. The computer model predicts a large drop in OHC from the volcanoes … which obviously didn’t happen. But instead of building on that reality of no OHC change after the eruptions, the reanalysis model has simply warped the real data so that it can show the putative drop after the eruptions.

And this is the underlying problem with treating reanalysis results as real data—they are nothing of the sort. All that the reanalysis model is doing is finding the most effective way to reshape the data to meet the fantasies, preconceptions, and errors of the modelers. Let me re-post the plot with which I ended my last post. This shows all of the various measurements of oceanic temperature, from the surface down to the deepest levels that we have measured extensively, two kilometers deep.

Figure 4. Oceanic temperature measurements. There are two surface measurements, from ERSST and ICOADS, along with individual layer measurements for three separate levels, from Levitus. NOTE—Figure 4 is updated after Bob Tisdale pointed out that I was inadvertently using smoothed data for the SSTs.

Figure 4. Oceanic temperature measurements. There are two surface measurements, from ERSST and ICOADS, along with individual layer measurements for three separate levels, from Levitus. NOTE—Figure 4 is updated after Bob Tisdale pointed out that I was inadvertently using smoothed data for the SSTs.

Now for me, anyone who looks at Figure 4 and claims that they can see the effects of the eruptions of Pinatubo and El Chichon and Mt. Agung in that actual data is hallucinating. There is no effect visible. Yes, there is a drop in SST during the year after Pinatubo … but the previous two drops were larger, and there is no drop during the year after El Chichon or Mt. Agung. In addition, temperatures rose more in the two years before Pinatubo than they dropped in the two years after. All that taken together says to me that it’s just random chance that Pinatubo has a small drop after it.

But the poor climate modelers are caught. The only way that they can claim that CO2 will cause the dreaded Thermageddon is to set the climate sensitivity quite high.

The problem is that when the modelers use a very high sensitivity like 3°C/doubling of CO2, they end up way overestimating the effect of the volcanoes. We can see this clearly in Figure 3 above, showing the reanalysis model results that Trenberth speciously claims are “data”. Using the famous Procrustean Bed as its exemplar, the model has simply modified and adjusted the real data to fit the modeler’s fantasy of high climate sensitivity. In a nutshell, the reanalysis model simply moved around and changed the real data until it showed big drops after the volcanoes … and this is supposed to be science?

Now, does this mean that all reanalysis “data” is bogus?

Well, the real problem is that we don’t know the answer to that question. The difficulty is that it seems likely that some of the reanalysis results are good and some are useless, but in general we have no way to distinguish between the two. This case of Levitus et al. is an exception, because the volcanoes have highlighted the problems. But in many uses of reanalysis “data”, we have no way to tell if it is valid or not.

And as Trenberth et al. have proven, we certainly cannot depend on the scientists using the reanalysis “data” to make even the slightest pretense of investigating whether it is valid or not …

(In passing, let me point out one reason that computer climate models don’t do well at reanalyses—nature generally does edges and blotches, while climate models generally do smooth transitions. I’ve spent a good chunk of my life on the ocean. I can assure you that even in mid-ocean, you’ll often see a distinct line between two kinds of water, with one significantly warmer than the other. Nature does that a lot. Clouds have distinct edges, and they pop into and out of existence, without much in the way of “in-between”. The computer is not very good at that blotchy, patchy stuff. If you leave the computer to fill in the gap where we have no data between two observations, say 10°C and 15°C, the computer can do it perfectly—but it will generally do it gradually and evenly, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15.

But when nature fills in the gap, you’re more likely to get something like 10, 10, 10, 14, 15, 15 … nature usually doesn’t do “gradually”. But I digress …)

Does this mean we should never use reanalyses? By no means. Kriging is an excellent example of a type of reanalysis which actually is of value.

What these results do mean is that we should stop calling the output of reanalysis models “data”, and that we should TEST THE REANALYSIS MODEL OUTPUTS EXTENSIVELY before use.

These results also mean that one should be extremely cautious when reanalysis “data” is used as the input to a climate model. If you do that, you are using the output of one climate model as the input to another climate model … which is generally a Very Bad Idea™ for a host of reasons.

In addition, in all cases where reanalysis model results are used, the exact same analysis should be done using the actual data. I have done this in Figure 3 above. Had Trenberth et al. presented that graph along with their results … well … if they’d done that, likely their paper would not have been published at all.

Which may or may not be related to why they didn’t present that comparative analysis, and to why they’re trying to claim that computer model results are “data” …

Regards to everyone,

w.

NOTES:

The Trenberth et al. paper identifies their deepest layer as from the surface to “total depth”. However, the reanalysis doesn’t have any changes below 2,000 metres, so that is their “total depth”.

DATA:

The data is from NOAA , except the ERSST and HadISST data, which are from KNMI.

The NOAA ocean depth data is here.

The R code to extract and calculate the volumes for the various Levitus layers is here.

Another superb posting, Willis. I would love to hear what a scientist (who supports the idea of AGW) makes of the ‘science’ of reanalysis data. For how long do we have to put up with the denigration of real science? I used to tell the children of my family how science is ‘real’ and not like religion. I used to tell them that they can trust it completely, that the very nature of science meant that it had to be accurate – that it was our best guess on something after rigorous examination and testing. Well, those days are gone now.

The UK Met Office continues to label Mt Pinatubo on its temperature graphs, for instance here:

http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/climate/seasonal-to-decadal/long-range/decadal-fc

I don’t understand why. For a start it looks as though the eruption happened just *after* temps had dropped. Perhaps this is due to an inaccurate graph. But more puzzling is that the dip in temperatures that happened around that time looks completely normal. There’s a very similar dip in the mid 50s. And one about 1964. Another one in the mid 70s. There’s one in the mid 80s, and one in the late 90s. Etc.

Thanks for an illustrative post. I liked your allution to the Procrustean Bed. So now we have procrustean data.

Good article.

I’d add one thing. It’s generally accepted that in order for a theory to be scientific, it must be ‘well articulated’. Which means someone with an appropriate background, with no prior knowledge of the theory, can take the theory and produce the same predictions from it, the originator and anyone else correctly interpreting the theory would.

This is the criteria the climate models fail, and why I argue, their output isn’t science. Which is not to say a well articulated climate model isn’t possible, but the current crop don’t make the grade.

I am perfecting a model for the weekly “Six from Thirty Six” lottery. I ran it about sixty million times and averaged all the models.

I then bet on number 18 coming up six times…

Good work Willis.

As I posted in you last thread, over rating volcanics is the key the exaggerating CO2. Since the real data does not support either it is now necessary to ‘reanalise’ it until it does.

The other thing that look pretty screwed in the model is that El Nino _boosts_ OHC. They rather foolishly hightlight this feature too.

Very good exposition of the True Nature Of Climate Models – And Modelers.

I can’t claim to have paid any meaningful attention to the internal workings of these things, but I am unaware of having come across a straightforward description before. Too much of “Climate Science” is lost in the earnestness of parsing details so as to establish the validity or not of a preferred interpretation, whilst not really paying attention to the actual validity of the whole damn process in the first place.

Lots of people quite rightly point out problematic aspects, or again rightly say that these are models not reality, but to illustrate the essentially manufactured nature of models in this simple way is rarely done.

Thanks for your lucid explanations.

Two comments.

Re-analysis of weather works to some extent because a lot of relevant data have been collected which can constrain the model quite effectively. It can be useful, if only to produce “complete” atmospheric states in a regular format including many poorly observed variables, so there is more to learn from and it can be done easier.

Ocean reanalysis is much less effective: there is a severe lack of data which could effectively constrain the model (most data is at or near the surface, you can’t easily collect profiles), while the spatial scales of the processes are much smaller than in the atmosphere so you would need a lot more. People call it “ocean reanalysis” but this type of product is in no way comparable to an atmospheric reanalysis. This is not likely to change.

About all reanalysis: it is hard to verify a state-of-the-art product, since almost all data went into it (in some cases it can be done though). For the atmosphere, the same models are used for weather forecasting, so quite a lot is known about (forecast) skill, which helps. This is not the case with ocean models.

One thing that stands out in 0-100m line in figure 4 is that there are three notable events

Big drops in OHC, as well as I can read off that scale they’re centred on 1971 1985 1999. Even 14 year intervals. One of them coincidentally matches a volcanic eruption.

This needs to be examined in the annual or 3monthly data to avoid getting fooled by runny mean distortions, but It has been noted elsewhere that the drop in SST around El Chichon actually starts well before the eruption.

Thank you, Willis. I learn something every time I read one of your posts. Excellent stuff and crystal clear.

Willis,

If what you describe is correct then Fig 1. in the Trenberth paper would be classified as fraud in any other field. For example a similar procedure applied in the search for the Higgs Boson at CERN would have generated a signal from nothing by “correcting” the raw data by a (complex) model that assumes its existance. Instead you can only compare the measured raw data with the simulated signal predicted by the model. Only if the two agree can you begin to claim a discovery. You show clearly that in fact the raw Leviticus data indeed show no such volcanic signal.

“Now for me, anyone who looks at Figure 4 and claims that they can see the effects of the eruptions of Pinatubo and El Chichon in that actual data is hallucinating. There is no effect visible.”

Put in a 5 year filter and you will see it too.

Paywalled? Should be here.

[Thanks, Nick, I’ve added it to the head post and acknowledged you for finding it. -w.]

Cees de Valk says:

May 11, 2013 at 1:18 am

Thanks for the thoughts, Cees. However, I disagree. Look at the problems in Figure 1 with the pre-1980 results from the five reanalysis model runs. That wide range in results is because the reanalyses are poorly constrained by the pre-1980 data. However, after 1980 this is much less the case, with the five model runs becoming very similar.

And since the introduction of the Argo data, the constraints have gotten even tighter.

So your claim, that the problem is that the data doesn’t constrain the reanalysis, is clearly untrue. The more recent results shown in Figure 1 are very close together, meaning that they are tightly constrained … but unfortunately, despite being well constrained they are also wrong …

w.

Willis: I will agree that I’ve never seen dips and rebounds from volcanic eruptions in global ocean heat content data, but it should be visible in sea surface temperature data. The sea surface temperature data in your Figure 4 appears to be smoothed with a 5-year filter… http://oi43.tinypic.com/2ztal54.jpg

…while the ocean heat content data looks as though it’s annual data. Please confirm.

The 1982/83 El Nino and the response to the eruption of El Chichon were comparable in size so they were a wash in sea surface temperature data, but Mount Pinatubo was strong enough to overcome the response to the 1991/92 El Nino, so there should be a dip then. The 5-year filter seems to suppress the response of the sea surface temperature data to Mount Pinatubo.

Also if you present the sea surface temperature data in annual form in your Figure 4, then the dip in the subsurface temperatures for 0-100 meters caused by the 1997/98 El Nino will oppose the rise in sea surface temperatures then.

Regards

lgl says:

May 11, 2013 at 1:49 am

Been there, tried that with a 5-year centered Gaussian filter, and I still couldn’t see the slightest sign of an effect from the eruptions. Your move.

w.

As Tamsin Edwards would say, ‘all models are wrong, but some can be useful’.

Overall I think most observations and conclusions in this article are correct. There are still things with which I don’t agree, though.

For instance in Figure 2, model runs “plunging to snowball earth” are not significant part of the dataset. Their presence does not make the whole simulation invalid. Significant part, i.e. majority of runs actually holds up to constant value. The important thing there is that the object of the research was comparison of (simulated) situation with “normal CO2” versus situation with “doubled CO2” and the result definitely allows to perform such comparison. Of course the result is limited to accuracy of the modelling itself and it is certain that these models are not perfect as there is no perfect climate model on the Earth yet. There’s of course no guarantee that even the average result is reliable, but that’s not because some runs diverge but because of unknown amount of physics not simulated by the model which may have significant influence on climate.

Regarding Figure 3, Trenberth’s reanalysis is about the 0-700 m layer so comparing 0-2000 m data is somewhat irrelevant to it. Levitus sure produced also 0-700 m measurements so I guess you could have compared these. But I guess I can see the problem. They actually have dents corresponding to Trenberth’s “reanalysis” data, don’t they? Maybe just not as big.

ftp://kakapo.ucsd.edu/pub/sio_220/e03%20-%20Global%20warming/Levitus_et_al.GRL12.pdf

Figure 4 makes up for Figure 3 a bit except Trenberth’s data are not present in it for comparison (and in corresponding format) I agree that smoothing might obscure the data but so does presenting data in different formats to make direct comparison hard. The data processing is different from Trenberth (annual means instead of smoothed monthly means) but it contains observable signal for surface temperature and 0-100 m layer (very noisy, probably statistically insignificant but observable), but definitely no signal for bigger depths.

It would be nice to have all three volcanic eruptions marked in your graphs, though.

QUESTION: “We need more money! How do we get more money without doing science?”

ANSWER: “Easy! When you run out of science, just baffle them with bullnalysis….”

Willis

If you give me your fig.4 data on .txt or .xls 🙂

Bob Tisdale says:

May 11, 2013 at 2:14 am

Thanks, Bob. As usual, you are right. I was still inadvertently using the 5-year average data from the previous analysis. I’ve updated Figure 4 with the correct annual SST data.

I still don’t see any volcanic effect, though. The drop post 1991 is absolutely bog-standard and indistinguishable from half-a-dozen other such drops in the record.

w.

Bob

“the dip in the subsurface temperatures for 0-100 meters caused by the 1997/98 El Nino will oppose the rise in sea surface temperatures then.”

No Bob, the 1997/98 El Nino heated the ocean. That heat is found two years later in the 100-700m layer, which has misled you to believe La Nina is heating the ocean.

http://virakkraft.com/SST-SSST.png

Kasuha says:

May 11, 2013 at 2:27 am

First, I posted that graphic to show that the effect of accumulated error can send a model into a tailspin.

Second, by appearances about 1% of the models fell off of the rails. The earth (despite huge provocation) has not fallen off the rails in the last half a billion years. If the real earth had a 1% failure rate, it would have gone off the rails long, long ago. This means that there is some serious problem with the model.

Perhaps that impresses you. Me, I see that the earth doesn’t have a 1% failure rate, which means that the model contains some kind of fundamental errors. Does that affect the “comparison of (simulated) situation with “normal CO2″ versus situation with “doubled CO2″”?

Who knows … but it certainly doesn’t give me the slightest desire to draw any conclusion from the results.

Oh, please. That’s splitting hairs. The model is going off of the rails because of the “physics not simulated by the model”, so what’s the difference between the model going off the rails and the physics not being properly represented in the model? End result is the same, it goes off the rails.

Please don’t make accusations that I’m avoiding graphs because of what they show. You might do that kind of thing, I have no idea.

I don’t do that, and I don’t appreciate your nasty insinuations. I have in fact shown the 0-700m Levitus measurements in Figure 4, and the Trenberth results are in Figure 1. But if you’d like them separated out, here they are:

Figure 3.

Figure S1. Levitus and ORAS4 data for the 0-700 m layer.

As you can see, the 0-700 metre layer shows nothing more about the effects of the volcanoes than does Figure 3 showing the 0-2000 metre layer. I considered putting in the 1-700 metre data, but I left it out. However, I did so for the OPPOSITE REASON from what you speculate—not because it contradicted my thesis, but because it added no new information that was not shown in Figure 3. Which is hardly surprising, since the post-1980 correlation between the 0-700 and the 0-2000 m ORAS4 layers is about 0.9.

There is a limit to how much data I can put on one graph, and on the number of graphs folks will look at before dropping it. I try to balance them, so at times I leave things off of graphs.

Your complaint that Trenberth uses monthly means and I have processed it differently ignores the fact that the real data is annual, not monthly. So if there is a fault here it is not mine, I can’t manufacture monthly data the way that Trenberth did …

I put Mt Agung on Figure 4. Comparing it to Trenberths results is meaningless given the huge error bars. With error bars like that, we have no clue even as to whether the data is rising or falling, because in those early model results, one year is not statistically different from any other.

In any case, there is no sign of Mt. Agung in the actual records … so whether it shows up in the reanalysis nonsense is not particularly meaningful.

Thanks,

w.

lgl says:

May 11, 2013 at 2:42 am

Why go the long way around via txt or xls? Here’s the data in comma-separated (CSV) format:

Rock on …

w.