Guest Post by Willis Eschenbach

Eleven years ago I published a post here on Watts Up With That entitled “The Thermostat Hypothesis“. About a year after the post, the journal Energy and Environment published my rewrite of the post entitled “THE THUNDERSTORM THERMOSTAT HYPOTHESIS: HOW CLOUDS AND THUNDERSTORMS CONTROL THE EARTH’S TEMPERATURE“.

When I started studying the climate, what I found surprising was not the warming. For me, the oddity was how stable the temperature of the earth has been. The system is ruled by nothing more substantial than wind, wave, and cloud. All of these are changing on both long and short time cycles all of the time. In addition, the surface temperature is running some thirty degrees C or more warmer than would be expected given the strength of the sun.

Despite that, the earth’s temperature has stayed in a surprisingly narrow range. The HadCRUT global surface temperature shows that the range of the temperature trend was 13.9°C ± 0.3°C over the entire 20th Century. This represents a temperature variation of ±0.1% during a hundred years. That stability was the curiosity of curiosities for me, because to me that temperature stability was clear evidence of some kind of a strong thermoregulatory system. But where and what was the regulating mechanism?

The short version of my hypothesis is that a variety of emergent phenomena operate in an overlapping fashion to keep the earth’s temperature stable beyond expectations. These phenomena include tropical cumulus clouds, thunderstorms, dust devils, squall lines, tornadoes, the La Nina pump moving warm water to the Poles, tropical cyclones, and the Julian-Madden, Pacific Decadal and North Atlantic Oscillations. In addition, I’ve adduced a large body of evidence supporting my hypothesis.

So I was interested to see Judith Curry, in her marvelous weekly post entitled “Week in review – science edition“, had linked to a paper I’d never seen. It’s a paper from 2010 by Marat F. Khairoutdinov and Kerry A. Emanuel (hereinafter K&E) entitled AGGREGATED CONVECTION AND THE REGULATION OF TROPICAL CLIMATE, available here. Inter alia they say:

Moist convection in the Earth’s atmosphere is mostly composed of relatively small convective clouds that are typically a few kilometers in horizontal dimension (Byers and Braham, 1948, Malkus, 1954). These often merge into bigger clusters of ~10 km in horizontal dimension, such as air-mass showers. More rarely, under special circumstances, moist convection is organized on even larger scales; this includes squall lines (e.g. Houze, 1977), mesoscale convective complexes, (e.g. Maddox, 1980), and tropical cyclones.

…

One of the robust characteristics of self-aggregation is the rather dramatic change in the mean state that accompanies it. In particular, in all non-rotating experiments (Bretherton et al., 2005) and an experiment on an f-plane (Nolan et al., 2007), self-aggregation leads to dramatic drying of the domain-averaged environment above the boundary layer. This appears to be the result of more efficient precipitation within the convective clump as more of the condensed water falls out as rain and less is detrained to the environment, per unit updraft mass flux. Such dramatic drying would reduce the greenhouse effect associated with the water vapor, and thus, would lead to cooling of the SST, which in turn may disaggregate convection. This would re-moisten the atmosphere, increasing the water-vapor greenhouse effect, and, consequently, warming the system. So, as in self-organized criticality (SOC), the tropical state would be attracted to the transition critical state between the aggregated and disaggregated states.

Let me point out a few things about their most interesting study. First, they are clear that a strong effect of the aggregated thunderstorms is to regulate the tropical temperature … just as I’ve been saying for years.

Unfortunately, their study is model-based. This is always frustrating to me because there is no way to check either the quality of their models or how many runs ended up on the cutting room floor …

However, given that shortcoming, their study points to something I noted in my original post—not just aggregated thunderstorms but also individual thunderstorms dry out the air in between them. This has two big cooling effects on the surface.

First, the dry descending air allows for increased evaporation from the surface, because the dry air can pick up more moisture from the surface. This increased evaporation cools the surface.

In addition to the increased evaporation, the effect they discussed is that the dryer air descending around the thunderstorms reduces the amount of the world’s main greenhouse gas, water vapor, that is between the surface and outer space. This allows the surface to radiate more freely to space, which also tends to cool the surface.

In their summary they say:

Idealized simulations of radiative-convective equilibrium suggest that the tropical atmosphere may have at least two stable equilibrium states or phases, one is convection that is random in time and space, and the second is the spontaneously aggregated convection. In this study, we have demonstrated using a simplified and full-physics cloud-system-resolving models that there is an abrupt phase transition between these two equilibrium states depending on the surface temperature, with higher SST being conducive to the aggregation. A significant drying of the free troposphere and consequent reduction of the greenhouse effect accompany self-aggregation; thus, the sea-surface temperature in the aggregated state tends to fall until convection is forced to disaggregate.

So, big credit to them for noticing the thermostatic effect in the tropics. However, their look is tightly focused. They have looked only at one cooling mechanism. In addition, they have only looked at two of what are at least four of what they call stable equilibrium states or phases. However, again to their credit they’ve said “at least” two stable states, acknowledging the existence of others.

Since Khairoutdinov and Emanuel had demonstrated using models that dry air increased with increasing aggregated thunderstorms, I thought I’d take a look at, you know … observations. Data. Crazy, I know, since so much attention is paid to models, but I’ve been a computer programmer far too long to put much faith in models.

STABLE STATES

Let me start by saying that they are looking at the third and fourth stable equilibrium states in the entire spectrum of the daily tropical thermally-driven threshold-based atmospheric response to increasing surface temperature. Each of these steps involves self-organized criticality.

In the tropics, by dawn, particularly over the ocean, the night-time atmosphere is generally stable and thermally stratified, with clear skies at dawn.

The first step is when the solar warming of the surface warms the air above it enough to initiate the stable equilibrium state called Rayleigh-Benard convection. As is common with such self-organized transitions, once the critical transition temperature is exceeded, the change between states is rapid.

Once Rayleigh-Benard circulation is established, areas of ascending air are interspersed with areas of descending air. The areas of rising air, often called “thermals”, transfer surface heat and surface water vapor upwards. This cools the surface directly through conduction, because the air traveling across the surface picks up heat from the surface. The R-B circulation also increases thermal radiation to space from the upward movement of the warm air above the lowest atmosphere, which contains the greatest amount of greenhouse gases.

Finally, the R-B circulation increases evaporation by moving the surface moisture upwards and mixing some of it into the lowest part of the troposphere. This transition to R-B circulation is generally invisible, although the onset of daily overturning can sometimes be felt in the wind.

The second transition is again temperature-based. It occurs when the surface temperature is large enough to drive the Rayleigh-Benard circulation higher into the troposphere. In the tropics, this transition typically happens in the late morning. When the water vapor in the ascending columns of the Rayleigh-Bernard circulation is moved upwards to the “LCL”, the “lifting condensation level” where water vapor condenses, at that altitude cumulus clouds form. The water vapor in the air condenses into the familiar puffy cotton-ball cumulus clouds. Each individual cumulus cloud group sits like a flag marking an ascending part of the Rayleigh-Benard circulation shown above.

Again, the transition is rapid. In the space of about a half-hour, the entire tropical atmospheric horizon to horizon can go from clear air to a fully developed cumulus field. And again, the transition is temperature-based. Below a certain temperature, there are hardly any cumulus clouds at all. Above that temperature, suddenly there are lots of cumulus clouds.

The third transition occurs when a somewhat higher temperature threshold is exceeded. The third stage of development is when individual cumulus clouds self-aggregate into scattered cumulonimbus. They build tall cloud towers, and the rain starts.

After this transition to the thunderstorm state, large areas of descending dry air form around each thunderstorm. This is the return path of the air that was first stripped of water in the base of the thunderstorm. When the water vapor condenses it gives up heat. The heated air then moves up the thunderstorm tower, emerges at the top, and descends as dry air in the areas around the thunderstorm.

This stage, of active thunderstorms, is well illustrated in the most entrancing simulation shown below. The colored layer added at one minute twenty seconds shows the temperature of that layer, with dark blue being coldest and red/orange being warmest.

The fourth and final transition occurs only in certain conditions at the highest transition temperature, when individual thunderstorms self-aggregate into squall lines and supercells, medium-scale convective complexes, and tropical cyclones. This is the only one of the four stable equilibrium states studied by Khairoutdinov and Emanuel. As with the other transitions, they point out that it is associated with a transition temperature. Like the thunderstorm regime, areas of descending dry air form around the aggregated phenomena. Here’s a photo of a single squall line from space.

It is worth noting that each of these succeeding stages exhibits an increase in the rate at which the surface loses heat. With each transition, the rate of surface heat loss increases from a variety of causes. The cause that is discussed by K&E, increased radiation to space through drier air, is only one among many.

The first transition, from quiescent stratified night-time atmosphere to Rayleigh-Benard circulation, increases surface heat loss to the atmosphere through conduction and convection of both latent and sensible heat. It encourages atmospheric loss to space by moving the surface heat up above the lowest atmospheric levels with their denser concentration of the greenhouse gases, mostly water vapor and CO2. It mixes surface heat and surface water vapor upwards. Because water vapor is lighter than air, the ascending areas are moister and the descending areas are dryer in the R-B circulation.

The second transition, to the cumulus field, adds two new methods of cooling the surface. First, energy is moved from the surface aloft in the form of latent heat. This heat is released when the rising columns of air condense into clouds. The sun then re-evaporates the water from the upper surface of the clouds, and the water vapor mixes upwards. This moves the surface heat well up into the lower troposphere.

The cumulus field also cools the surface by reflecting sunlight back to space. This is a very large change in the energy balance, on the order of a couple of hundred watts per square metre or so. The timing and density of the emergence of the cumulus field is one of the major thermal regulation mechanisms. How strong is this regulatory action? Here’s a typical day’s available solar energy, measured at ten-minute intervals at a TAO buoy in the Equatorial Pacific Ocean.

The deep notch in the available solar energy from clouds covering the sun at around 11:30 AM in the graphic above is quite typical of the drop when clouds cover the sun. On this day it lasted about half an hour. It reduced the available solar energy flux by about six watts per square metre averaged over that 24 hour period.

By comparison, a theoretical doubling of CO2 from the present, which is highly unlikely to happen, would add a flux of about 3.7 watts per square metre during that 24 hour period.

So in that area, that one cloud would be more than enough to cancel out even a doubling of CO2 for that day … and that is just one of the many ways the surface is being cooled by emergent phenomena.

The third transition, from developed cumulus field to scattered thunderstorms, adds the whole range of new surface cooling methods that I list in the endnotes. And unlike the first two transitions, thunderstorms can actually cool the surface to a temperature below the temperature needed to initiate the thunderstorms. This allows thunderstorms to maintain surface temperatures. When any location gets hot a thunderstorm forms and cools the surface back down, not just to where it started, but down below the onset temperature. This “overshoot” is the signature of a governor as opposed to a simple linear or similar feedback. Simple feedback can only reduce a warming tendency. A governor, on the other hand, can turn warming into cooling.

In the fourth transition, the transition to the larger self-aggregated phenomena like squall lines, supercells, and the like, no new surface cooling methods are added. What happens instead is that the previous methods move to a new level of efficiency. For example, thunderstorms self-organize into squall lines as shown in the photo above.

Instead of individual areas of descending air around each individual thunderstorm, in a thermally-driven squall line you get long rolls of dry descending air along the flanks of the squall line. Because the carpet-roll-type circulation is streamlined, with the air smoothly rolling in a long tube, the squall line moves more energy from the surface to the upper troposphere than would be moved by the same number of individual thunderstorms.

To summarize the discussion so far:

There are four distinct successive emergent transitions from a quiescent stratified atmosphere to fully developed squall lines. Each is the result of self-organized criticality. Each one is a separate emergent phenomenon, coming into existence, persisting for some longer or shorter time, and then disappearing. In order, the transitions and the new emergent phenomena are:

- Still air to Rayleigh-Benard circulation

- Rayleigh-Benard circulation to cumulus field.

- Cumulus field to scattered thunderstorms

- Scattered thunderstorms to aggregated thunderstorms.

Each transition removes more energy from the surface to the atmosphere and thus eventually from the system.

Khairoutdinov and Emanuel discuss drying of descending air in only one of the states, the fourth one where thunderstorms aggregate. They are correct. However, this does not begin at the fourth stage. All the stages dry the descending air. And after each succeeding transition, the air becomes dryer and dryer.

I’ve demonstrated the close dependence of thunderstorms and “aggregated” thunderstorms on the surface temperature. I made up a movie showing this a while back using the CERES data, hang on … OK, here it is. I am using the extent of deep convection as measured by the cloud top heights as a measure of the strength of the thunderstorms and aggregates.

In the movie, you can see the thunderstorms and aggregated thunderstorms (color) following the warm water (gray lines) around the Pacific throughout the year.

And if we take a scatterplot of average cloud top altitude versus sea surface temperature, we find the following relationship:

Just as we saw in the movie above, when the sea surface temperature goes over about 26°C thunderstorms explode vertically, getting taller and taller. This is clear support for the idea that the transition between states is temperature-threshold based.

With all of that as prologue, let me move to the question of the descending dry air between the thunderstorms. I realized that we actually have some very good information about the amount of water in the air. This is data from the string of what are called the TAO/TRITON buoys and other moored buoys that stretch on both sides of the Equator around the world. Here are their locations.

Let me begin with another look at rainfall and temperature. Here’s a scatterplot of the sea surface temperature versus the rainfall in the equatorial Pacific area shown by the yellow box above (130°E – 90°W, 10°N/S). The blue dots below show results from the TAO buoys in the yellow box. The red dots show gridcell results from the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite rainfall data and Reynolds OI sea surface temperatures.

Man, I do love it when several totally independent datasets agree so well. In the graph above the blue dots are co-located measurements of average rainfall and sea surface temperature at individual TAO/Triton buoys. The red dots are 1° latitude by 1° longitude averages of Reynolds OI Sea Surface Temperatures, and Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite-based rainfall data. And in both datasets, we see once again that thunderstorms start forming in numbers only when sea surface temperatures get above about 26°C.

It’s also interesting that once the sea surface temperature gets into the upper-temperature range, there are no dry areas. Every place gets at least a certain minimum amount of rain. Not only that, but the minimum amount of annual rainfall increases smoothly and exponentially as the average sea surface temperature goes up.

Why is it so important that this threshold is temperature based? It’s important for what it is NOT. It is not forcing based. In other words, the great global thunderstorm-based air-conditioning and refrigeration system kicks in at about 26°C, no matter what the forcing is doing. No matter what the CO2 is doing. No matter what the volcanoes are doing. The regime shift from puffy white cumulus clouds to scattered thunderstorm towers kicks in when the temperature passes a temperature threshold, and not before, regardless of what CO2 does.

And this, in turn, means that these successive regime shifts, first to Rayleigh-Benard circulation, then to the cumulus field, then to scattered thunderstorms, and finally to aggregated thunderstorms, are functioning in a host of different ways to regulate and cap the surface temperature.

And finally, by a fairly circuitous but interesting route, we’ve arrived back at the question of the drying of the air in between the thunderstorms and thunderstorm aggregations.

There are eight TAO buoys that are directly on the Equator across the Pacific. It’s an interesting group because they all get identical sunshine. Despite getting identical solar energy, there is a temperature gradient from Central America across to Asia, with the Asian end at about 29°C and the South American end at about 24°C. So looking at these eight buoys gives us a look at how some phenomena vary by temperature.

Using the temperature and the relative humidity measurements from these buoys, I calculated the absolute humidity for each of them. This is the amount of water that is present per cubic metre of air. That number is important because the absorption of long-wave radiation by water vapor varies proportionally to the absolute humidity, not the relative humidity. Less absolute humidity means more surface heat loss by long-wave radiation to space.

These observations from the buoys are done every ten minutes. This allows me to calculate what an average day’s variations look like. To understand the daily variations, I aligned them at the morning minimums. Here are the records of those eight TAO buoys that are directly on the Equator.

In this graph, note that the warmer that the sea surface temperatures are, the smaller the 10 AM peak, and the more the afternoon absolute humidity drops from the 10 AM peak.

This is because as the thunderstorms form and increase the local area moisture is concentrated in the small area in and under the thunderstorms, with descending dry air between the thunderstorms making up the bulk of the lower troposphere. And in areas with warmer sea surface temperatures, shown in red above, clouds and thunderstorms form earlier, are denser, and at times form even larger aggregations of thunderstorms.

Now, what I’ve shown above are long term full-dataset averages. So it’s tempting to think “well, thunderstorms only happen where the average temperature is over 26°C”. But thunderstorms are not touched by averages. These temperature-regulating phenomena can appear, persist, and disappear at any time of day. All that matters are the instantaneous conditions. Whenever the tropical ocean gets warm enough, regardless of the longer-term averages for that location, you are likely to see thunderstorms form. All the averages mean is that the surface gets sufficiently hot to create thunderstorms on more or fewer days of the year.

My conclusions?

• K&E were right about the drying power of aggregated thunderstorms.

• It is also true that individual thunderstorms, as well as cumulus clouds and Rayleigh-Benard circulation, dry out the descending air.

• This lower level of water vapor cools the surface by increasing radiation loss to space and by increasing evaporation.

• This is only one of the host of ways that cumulus clouds and thunderstorms keep the tropics from overheating

• Rayleigh-Benard circulation, cumulus fields, scattered thunderstorms, and aggregated thunderstorms are all emergent phenomena. They emerge wherever there is sufficient surface heat, meaning when the temperature exceeds some local threshold. Each succeeding state, in turn, starts removing more heat from the surface. This is an extremely efficient temperature regulating system because they emerge only as and where there are local concentrations of surface heat.

Finally, I want to emphasize one of K&E’s interesting claims:

Such dramatic drying would reduce the greenhouse effect associated with the water vapor, and thus, would lead to cooling of the SST, which in turn may disaggregate convection. This would re-moisten the atmosphere, increasing the water-vapor greenhouse effect, and, consequently, warming the system. So, as in self-organized criticality (SOC), the tropical state would be attracted to the transition critical state between the aggregated and disaggregated states.

In other words, all of these phenomena act to stabilize the temperature.

Here, sunshine. Life is good. My very best wishes to all.

w.

My Usual Request: When you comment please quote the exact words that you are referring to, so we can all understand your subject.

ENDNOTE—COOLING MECHANISMS

K&E are looking just at increased radiation through dryer air. This is only one of the many ways that thunderstorms cool the surface. Here’s a more complete list.

• Refrigeration-cycle cooling. A home refrigerator evaporates a working fluid in one location and condenses it in another location. This removes heat in the form of latent heat of evaporation/condensation. The thunderstorm uses the exact same cycle. For the thunderstorm the working fluid is water. Water evaporates at the surface and is carried aloft via the thunderstorm circulation. This, of course, removes surface heat in the form of latent heat. Then, just as in a domestic refrigeration cycle, the working fluid condenses at altitude in the thunderstorm base and falls back as a cold liquid to the surface.

• Self-generated evaporative cooling. Once the thunderstorm starts, it creates its own wind around the base. This self-generated wind increases evaporation in several ways, particularly over the ocean.

- a) Evaporation rises linearly with wind speed. At a typical squall wind speed of 10 mps (20 knots), evaporation is about ten times higher than at “calm” conditions (conventionally taken as 1 mps).

- b) The wind increases evaporation by creating spray and foam, and by blowing water off of trees and leaves. These greatly increase the evaporative surface area, because the total surface area of the millions of droplets is evaporating as well as the actual surface itself.

- c) To a lesser extent, surface area is also increased by wind-created waves (a wavy surface has a larger evaporative area than a flat surface).

- d) Wind created waves in turn greatly increase turbulence in the atmospheric boundary layer. This increases evaporation by mixing dry air down to the surface and moist air upwards.

• Wind-driven albedo increase. The white spray, foam, spindrift, changing angles of incidence, and white breaking wave tops greatly increase the albedo of the sea surface. This reduces the energy absorbed by the ocean.

• Cold rain and cold wind. As the moist air rises inside the thunderstorm’s heat pipe, water condenses and falls. Since the water is originating from condensing or freezing temperatures aloft, it cools the lower atmosphere it falls through, and it cools the surface when it hits. In addition, the falling rain entrains a cold wind. This cold wind blows radially outwards from the center of the falling rain, cooling the surrounding area.

• Increased reflective area. White fluffy cumulus clouds are not tall, so basically they only reflect from the tops. On the other hand, the vertical pipe of the thunderstorm reflects sunlight along its entire length. This means that thunderstorms shade an area of the ocean out of proportion to their footprint, particularly in the late afternoon.

• Modification of upper tropospheric ice crystal cloud amounts (Lindzen 2001, Spencer 2007). These clouds form from the tiny ice particles that come out of the smokestack of the thunderstorm heat engines. It appears that the regulation of these clouds has a large effect, as they are thought to warm (through IR absorption) more than they cool (through reflection).

• Enhanced night-time radiation. Unlike long-lived stratus clouds, cumulus and cumulonimbus often die out and vanish as the night cools, leading to the typically clear skies at dawn. This allows greatly increased nighttime surface radiative cooling to space.

• Delivery of dry air to the surface. The air being sucked from the surface and lifted to altitude is counterbalanced by a descending flow of replacement air emitted from the top of the thunderstorm. This descending air has had the majority of the water vapor stripped out of it inside the thunderstorm, so it is relatively dry. The dryer the air, the more moisture it can pick up for the next trip to the sky. This increases the evaporative cooling of the surface as well as allowing more radiative loss to space.

This is a great article by Willis Eschenbach on heat transfers within the atmosphere and explains a lot of observable actions of clouds especially in the tropics. It is a refreshing antidote to the endless Climate Change / Global Warming articles on the transfer of wealth within the Socialist atmosphere.

Thanks, Nicholas, appreciated.

w.

always love reading your dissertations, willis. they are clear, detailed and thorough. thank you

I second this remark!

Also, K&E should have cited your previous work in their references. They effectively plagiarized your work without giving you credit.

Thanks for the kind words, Louis. However, I neither accuse K&E of plagiarism nor do I bother about credit. I learned early on in life that I can accomplish almost anything if I don’t care who gets the credit …

w.

In other words, all of these phenomena act to stabilize the temperature. – article

Dagnabbit, Willis, you just smashed the biggest whine claimed by the Greenies!!! You’re gonna hurt their feewings!!!

I much prefer the real results from real-time data over models, because models are limited and the real world is not. Chaos factor is never taken into account with modeling – NEVER. Chaos factor also explains why, when I don’t have a camera with me, the most fascinating columns of air that look like nuclear bombs as they rise are never photographed by me. Duh!!!

A master at work

This is absolutely fascinating and a valuable contribution to climate science.

Valuable.. yes, possibly the MOST valuable.. “the cooling effect is independent of forcing”. That’s a big hello to CO2, aerosol alarmists. Dr. Lindzen used data to calibrate his Iris effect and that suggested a climate sensitivity of 0.7C. W.E. might up the ante to 0.5 C or smaller.

This looks to be what I described as a “hard stop”: a feature in the earth’s climate that creates massive negative feedbacks effectively stopping warming. The key to proving it is this “hardstop” is to show it exists at ~26C no matter what the climate is doing and not that it just happens to be 26C … for the moment.

I wrote to you several times about this but you did not reply. That in large part was why I’ve stopped working on climate.

Mike, I receive lots of emails, and I fear I don’t remember yours.

In any case, all I can show is what I’ve shown using historical data. Yes, it’s possible that there would come some fundamental change that would shift the temperatures related to the various transitions between states … but we have no alternate earth to test that.

w.

Great article, Willis. It not only provides a powerful argument against the CO2-as-control-knob hypothesis but explains why there has been warming in high latitudes in the post-1970s while temperatures in the equatorial region have done nothing.

Intuition tells me that the 26°C threshold and the 30°C absolute limit are fixed, and are defined by the physical properties of water and air. Those limits can’t change because … it just wouldn’t feel right. If it wasn’t late and I wasn’t tired, I might be able to articulate the thoughts behind that feeling. Or possibly not.

Changing salinity would probably vary those numbers by changing the partial pressure of water vapour in equilibrium with saline water, but it wouldn’t be by much within the range of normal ocean salinity.

You should probably do not say fixed. They are related to current air pressure. Theory is that atmospheric pressure is declining through eons, so this limit is changing with it.

Thanks, Peter. You are correct that they are not “fixed” in some eternal sense. Instead, as you’d expect, they are stable given the current boundary conditions such as air pressure, position of the continents, and the like.

w.

That’s interesting. I like Willis’ reasoning, and had just looked up ‘atmospheric pressure’ after one of my outside-the-GCM-black-box thoughts.

According to Wiki, average sea level pressure is 101.325 kPa. Let’s say that ten years ago it was also 101.325 kPa.

Then what “solid” evidence is there that there was a NET addition of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere over a decade from burning fossil fuels? However many gigatons of CO2 were added to the atmosphere would have displaced an equivalent weight of something that’s at least as abundant . Like water vapour… another greenhouse gas.

(And volume-wise that would be a twofer… two lighter GHG molecules eliminated for the price of one).

Another of the boundary conditions would be the tendency of clouds to form from super-saturated water vapour. This is where the cosmic ray theory comes in, increasing the tendency for clouds to form when the sun’s magnetic influence is low. If true, it would explain why the Earth’s temperature seems to be tied to solar variability.

Hivemind January 10, 2020 at 4:07 am

I have looked and looked, and have never found the slightest evidence that cosmic rays, or any other sunspot-related solar phenomena, have any affect on any surface weather phenomena (cloud levels, river flows, tides, sea levels, temperature, etc.). There’s about a dozen posts of mine on the subject here.

Best to all,

w.

I played around with calculating the enthalpy of air and water vapor at 100% RH, and somewhere around 26C the change in enthalpy with temperature was driven more by the water vapor than air. Seems to me that the threshold temperature would increase with increasing sea level pressure. Note that 26C is the minimum SST to sustain a tropical cyclone.

Willis had an interesting posting a few days back on CERES data indicating that the change in temperature for 3.7W/m^2 increase in downwelling radiation was less than a black body radiator for temperatures greater than 0C and more than the black body radiator for temperatures less than 0C. This would explain why the temperature response appears to show a positive feedback during glacial periods, and a very strong negative response during the interglacial periods.

Willis,

You are probably aware of these studies but, for others information, I will post them.

4 – McLean, J. (2014) – “Late Twentieth-Century Warming and Variations in Cloud Cover”, Atmospheric and Climate Sciences, October 2014, (available online free of charge at

http://www.scirp.org/journal/PaperInformation.aspx?PaperID=50837)

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/07/190703121407.htm

Winter monsoons became stronger during geomagnetic reversal

Revealing the impact of cosmic rays on the Earth’s climate

http://bit.ly/2Zc7Fhl

July 3, 2019

Source:

Kobe University

New evidence suggests that high-energy particles from space known as galactic cosmic rays affect the Earth’s climate by increasing cloud cover, causing an ‘umbrella effect’.

http://bit.ly/2KH9aAg

Finnish study finds ‘practically no’ evidence for man-made climate change

12 Jul, 2019

https://www.rt.com/news/464051-finnish-study-no-evidence-warming/

Also, here.

FINNISH STUDY

NO EXPERIMENTAL EVIDENCE FOR THE SIGNIFICANT ANTHROPOGENIC CLIMATE CHANGE

6/29/19

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1907.00165.pdf

A new paper published by researchers form the University of Turku in Finland suggests that even though observed changes in the climate are real, the effects of human activity on these changes are insignificant. The team suggests that the idea of man made climate change is a mere miscalculation or skewing the formulas by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Jyrki Kauppinen and Pekka Malmi, from the Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Turku, in their paper published on 29th June 2019 claim to prove that the “GCM-models used in IPCC report AR5 fail to calculate the influences of the low cloud cover changes on the global temperature. That is why those models give a very small natural temperature change leaving a very large change for the contribution of the green house gases in the observed temperature.”

The Thermostat Hypothesis

http://bit.ly/335zEl9

Abstract

The Thermostat Hypothesis is that tropical clouds and thunderstorms actively regulate the temperature of the earth. This keeps the earth at a equilibrium temperature.

Several kinds of evidence are presented to establish and elucidate the Thermostat Hypothesis – historical temperature stability of the Earth, theoretical considerations, satellite photos, and a description of the equilibrium mechanism.

Clouds form and rain starts during a day near the equator.

Thermostat regulate the suns effect.

…Finally, the equilibrium variations may relate to the sun. The variation in magnetic and charged particle numbers may be large enough to make a difference. There are strong suggestions that cloud cover is influenced by the 22-year solar Hale magnetic cycle, and this 14-year record only covers part of a single Hale cycle.

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2009/06/14/the-thermostat-hypothesis/

The Thermostat Hypothesis

http://bit.ly/335zEl9

Abstract

The Thermostat Hypothesis is that tropical clouds and thunderstorms actively regulate the temperature of the earth. This keeps the earth at a equilibrium temperature.

Several kinds of evidence are presented to establish and elucidate the Thermostat Hypothesis – historical temperature stability of the Earth, theoretical considerations, satellite photos, and a description of the equilibrium mechanism.

Clouds form and rain starts during a day near the equator.

Thermostat regulate the suns effect.

…Finally, the equilibrium variations may relate to the sun. The variation in magnetic and charged particle numbers may be large enough to make a difference. There are strong suggestions that cloud cover is influenced by the 22-year solar Hale magnetic cycle, and this 14-year record only covers part of a single Hale cycle.

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2009/06/14/the-thermostat-hypothesis/

Oops, sorry forthe replication. Not sure how I managed that other than I got distracted.

No worries. Thanks for the links, I’ll take a look.

w.

What I was suggesting was to compare an El Nino year like 2016 with non El Nino years. This would distinguish between two potential explanations: 1) that the effect was latitudinal and 2) that it was temperature based. (If latitudinal the “26” would change temperature as average global temp went up.)

If the temperature remained constant, then this would be strong evidence that we have a change in the climate that introduces a regime of strong negative feedbacks, and this explains both why the rapid ice-warming came to an abrupt end and also why each interglacial has been at approximatelyt he same temeprature (controlled by this “26C”).

It also explains why we can both have strong positive feedbacks for cooling/warming into/out of the glacial period, but still have a very stable regime in the interglacial period which prevents warming. It suggests the strong positive feedbacks are a combination of Ice-albedo effect and water vapour positive feedback (as in the atmosphere dries and that enhances cooling).

At the time I wrote, I was hoping to get help accessing the data for 2016, but unfortunately as there seemed no way to progress the subject, I’ve now started working on other things entirely unrelated to climate.

Hey, Mike, thanks for the reply.

I know that the effect is not latitudinal because, as I mentioned somewhere in the head post, I’ve looked at it along the Equator. There, the latitude is the same, as is the total available sunlight.

Best to you,

w.

How does geoengineering affect all this? ( I would imagine SAG &c might have an adverse affect0

Willis, are your aggregated thunderstorms what causes or forms atmospheric rivers that we occasionally see stretching from Hawaii to the west coast of the US?

Hadn’t considered it, but at first glance I’d say no. That’s a mass advection (horizontal movement) of air.

w.

I’m pretty sure that the so called atmospheric rivers are a creation of the jet stream.

The atmospheric river called the Pineapple Express seems to be related to the pumping action of a low pressure system positioned to the north, and high pressure system to the south. Air near the low pressure system is rushing towards the center in a counter clockwise spiral, the opposite with the high pressure system. This sets up a pumping action where air between the systems is pumped on both sides to form the atmospheric river.

On this day (oddly) in 2017 there was low off the Oregon coast and a high off the Baja coast. The river was running at 30 to 40 mph at the 5000 foot level and there was 40 kg of water vapor per square meter of ground surface and it rained a lot in California.

Atmospheric rivers are associated with Rossby waves, which are generated by planetary rotational (Coriolis) forces, to conserve potential vorticity. When zonal winds (east-west) are perturbed meridonally (north-south), Coriolis-induced rotation acts as a restoring force to limit the perturbation.

Rossby waves are responsible for a part of the meridional transports of momentum, energy and water vapor and they are thus an integrating part of the global circulation. Important to note that this circulation of the warm and cold air between the tropics and polar regions doesn’t _cause_ the Rossby waves, but is an _effect_ of these waves, which are caused by the rotation of the Earth.

They are _transverse waves_, that is the oscillation is perpendicular to the direction of travel, which is always from west to east. A parcel of air moving east is pushed to the right (southward) by the Coriolis effect, but this instability is offset by the need to conserve vorticity, which acts a restoring effect and eventually pushes the parcel northward again. This cycle repeats forever, creating a series of planetary waves which have always been there.

So these atmospheric rivers are typically located ahead of cold fronts pushed eastward by the leading edge of mid-latitude Rossby wave troughs.

Excellent. It looks like you’ve put together the foundations of a new empirically based climate model Willis! Many thanks for your work.

Bookmarked; added to my (lengthy) thermostat-hypothesis folder.

There also seems to be a connection to Richard Lindzen’s iris hypothesis. That, when it’s hotter, the precipitation gets more efficient, leaving less water vapor to be detrained into (the earth-warming) cirrus clouds and thereby providing negative feedback.

How do you envision the tropics to overheat? Tropics are mostly ocean, and a good day of sunshine in the tropics delivers some 25 MJ/m^2 to these oceans. Since the sun directly warms only the upper 5-10 m directly, this roughly enough energy to warm this column 1K. During the night this “stored” energy is lost again to the atmosphere/space.

Willis,

Great essay, will take several more reads to fully apreciate.

An immediate question, if I may? Regulating, governor systems typically have a set point that they strive to get back to. It can be set on mechanical systems and adjusted to suit the purpose. Like the weight of those revolving iron balls that move an adjustment sleeve up and down to hunt for a desired rotational velocity by a link to the throttle or steam pressure.

Question is, can we imagine a set point in this weather mechanism? You have often noted max SST of 27C, but what informs the mechanism that 27C has been reached? Intuitively, I look first for a physical mechanism like a phase change that is easy for the mind to envisage as having some needed properties. The concept of the weather comparing itself to this reference set point, then adjusting, is attractive by analogy to the mechancal feedback governor, but this might be false.

Any thoughts? Geoff S

Geoff,

If I’ve read your question right Willis has answered your question in previous postings on his governor theory, been to long since I’ve read them so trying to recite from memory will get things wrong. Reading through those should answer your question and probably bring up more. Bit surprised because normally he links all his previous articles to his current one but a it will just take a quick search on WUWT to turn up the articles.

Was smply asking if the early off-the-cuff response had matured with further thought and time.

People claim the globe has warmed naturally since the Little Ice Age. I ask by what mechanism.

Willis and others write about clouds governing global temperatures – which I consider to be excellent and progressive – and I ask about details of the mechanism. The purpose is to advance and clarify, not to snipe. Geoff S

Geoff, good question. I discussed this issue both in my initial offering on the subject, “The Thermostat Hypothesis“, as well as in a post called “Slow Drift in Thermoregulated Systems“.

w.

Hi Willis,

my theory about why hard limit of Earth thermostat is between 26-29C is this:

Energy for lift of air comes from two sources:

1. water vapor – steam is lighter than air, 1m3 of steam at 1 bar/100C weights 0.59kg comparing to 1.15kg of dry air

2. hot air – hotter air is lighter than cold

Potential energy formula is mgh. Weight of 1m3 air is 1.15kg, gravitational constatnt 9.8ms-2. What is important and only variable is h – height.

From this formula we can derive how high can 1.15kg of air get when receiving some amount of energy.

Absolute humidity at 30C is around 35g of water per m3 of air.

Vaporization/condensation energy of this amount of water is 79kJ (2257000J/kg x 0.035kg)

Heat energy of dry air is 11.6kJ (10C temperature daily swing, 1005J/kg capacity, 1.15kg per m3)

Together it is 90.6kJ of energy.

From mgh fromula we can get that this amount of energy can propel 1.15kg of air 8040m high.

This is very close to thunderstorm clouds height.

Condensation level is practically fixed. LCL (Lifted Condensation Level) as derived on Wiki is counted as 125(T-Td) where T is ground temperature and Td is dew point temperature.

So by providing sun energy we are lifting air mass proportional to this energy. When this mass reaches LCL height it starts to condense as cumulus and create negative feedback.

Simply all additional energy to system is creating cloud cover until system returns to base energy content.

Peter,

Getting close by describing a limited process, but does your mechanism adjust for changes in insolation? Less sun energy in means less lifting energy so less cooling so system is not stable? Geoff S

Geoff,

I’m not fully sure I got your question, but this mechanism apparently works as upper hard stop, so if you provide less lifting energy that simply means that clouds will not from at all or will form less energetic kinds. e.g. cumulus only, no cumulonimbus.

System can be stable with less energy budget. So with less insolation you can get to state where there is mild 23C with few cumulus on the sky never growing to storm for example.

Peter January 9, 2020 at 1:18 am

Rising air does indeed rise because it is lighter than the surrounding air.

The amount of Water Vapor is pretty much irrelevant for its weight, temperature is the deciding factor.

Rising air cools according the Dry Adiabatic Lapse Rate (9,8K/km) until it begins to condens.

The condensation releases latent heat, so the rising air now cools according the Saturated Adiabatic Lapse Rate, until all latent heat has been used, and it cools again according the DALR.

Of major importance in this proces is the temperature profile of the “static” atmosphere the convecting air rises into.

eg a temperature inversion will pretty much stop any convection.

Not really, it can be anywhere from close to ground level up to 2000m or higher.

In the tropics the warmer air can “hold” more WV and thus has more latent heat to “burn” while rising.

Usually thermodynamic diagrams are used to plot all these data.

See for a nice summary:

https://www.atmos.illinois.edu/~snesbitt/ATMS505/stuff/09%20Convective%20forecasting.pdf

Ben, I tried to approach this problem from totally different side, energy content point of view. You can derive dry Adiabatic Lapse Rate and find where condensation occur from PVT formula, use various functions, integrals etc.

So I looked on it from point of energy preservation, where I assume how high can warmed moist air reach. Directly change thermal and evaporation energy to potential energy.

Condensation level is practically fixed.

I meant that condensation level in absolute dry air and in tropics. Condensation level in moist air is just temporary state.

Otherwise condensation level in absolute dry air is linearly related only to ground air temperature, while energy content of WV in air is in exponential relation to temperature.

Ben Wouters January 9, 2020 at 4:00 am

Thanks, Ben. In fact, the amount of water vapor is crucial in the persistence of thunderstorms. This is because water vapor, with a molar mass of only 18, is much lighter than air with a molar mass of 29.

As a result, a thunderstorm is a dual-fuel engine. It starts on hot air. But once it gets going, the wind at the base greatly increases evaporation, making the air inside the thunderstorm lighter. At the same time, the air around the thunderstorm becomes dryer and thus heavier, increasing the density differential between the inside and outside of the thunderstorm tower.

This allows the thunderstorm to cool the surface to a temperature BELOW the initiation temperature … and this “overshoot” is critical in thermally regulating a system where there is lag in the response.

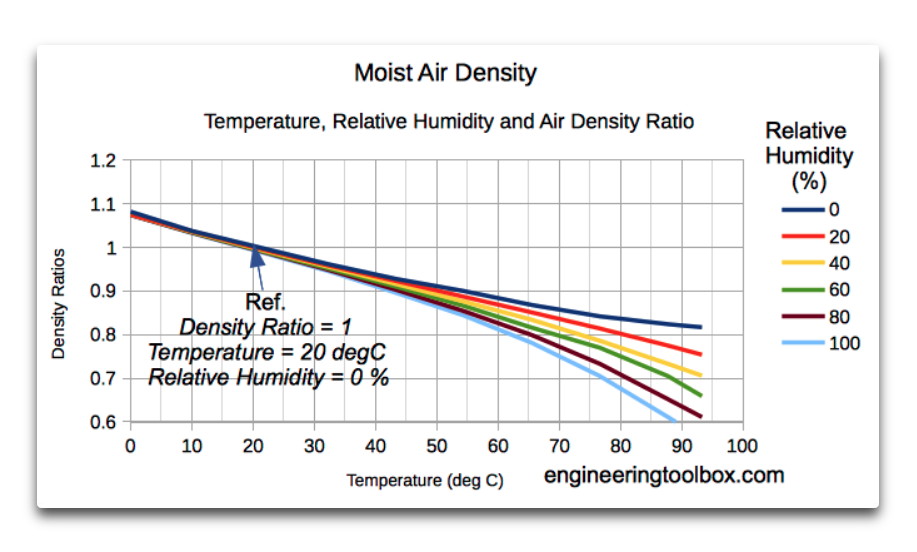

The difference in air density is illustrated below, from the Engineering Toolbox.

Best regards to you,

w.

Peter January 9, 2020 at 5:08 am

Willis Eschenbach January 9, 2020 at 8:38 am

An often seen misunderstanding. The amount of WV is indeed crucial, but the reason is the latent heat that is released during rising that slows the adiabatic cooling (DALR => SALR)

At atmospheric temperatures the weight difference between 0% and 100% RH is small to nonexistent.

At even lower temperatures hardly any WV will be present.

Once a volume is rising it will not be influenced by the surface anymore. Its WV content is set, its RH changes because the rising air cools according the DALR until it reaches condensation level, SALR thereafter.

See the large difference between DALR and SALR in this PDF:

https://www.atmos.illinois.edu/~snesbitt/ATMS505/stuff/09%20Convective%20forecasting.pdf

Ben, have column of absolute dry air RH 0%, start to pump in RH100% air with same temperature.

You will definitely have condensation level height for such scenario and will be fixed for given temperature (and air pressure, gravity…)

Really are you trying to tell me that buoyancy of moist air is coming from thin air and there is no energy needed for lifting?

For me math here is clear for 1kg of moist air to lift up 10km high you need energy and this energy is exactly from two sources – additional heat above local average and latent heat of vaporization.

In 10km height you will finally end up with same 1kg of dry air but stripped of water, releasing all its latent heat on the way up.

You need energy for buoyancy.

Peter January 10, 2020 at 1:05 am

You wrote earlier

Condensation level only applies to rising air, so I had to assume 0% RH for the rising air. Air at the surface at 100% RH is fog, so whatever the temperature the condensation level is at the surface.

Correct. Just as a boat can float indefinitely without burning any fuel, can a parcel of air rise without using any INTERNAL energy.

Actually the entire atmosphere below the parcel pushes it upward, so that is where the energy is coming from.

For a parcel to become lighter than surrounding you obviously need energy: the sun heating the surface and the surface heating the parcel. Once it has left the surface, it does NOT “burn” energy to rise.

Ben,

boat, or rather bottle can float indefinitely without energy, but you can not sink it any depth/height without any energy. And this is working in reverse with air in atmosphere. Buoyancy is created by energy income (by any means, heat, condensation) then affected mass is just surfacing at equilibrium height after losing this energy.

0m condensation level is just temporary dynamic state, where atmosphere column is not in ideal equlibrium state but somehow disrupted. For example cold front wedging under hot air…

And actual condensation level is function of air moisture. I’m speaking about 0% RH air.

So fog is just thermal thermostat mechanism in reverse process, what was put in the air by incoming energy is going back down after release of energy. Fog is only existing when negative flux of energy is present never positive.

Peter January 10, 2020 at 6:24 am

Exactly the same for the atmosphere. eg a helium balloon can float high in the atmosphere indefinitely, and has to be pulled down with force, just as a bottle floating in water. That’s buoyancy 😉

Anything will float in air or water as long as its density is equal to the density of the surrounding fluid. Higher density and it will sink (move towards the center of the earth), lower density and it will rise (move away from the center of the earth)

Not sure what you mean with 2nd part.

WV wil start to condense when the air cools below its dew point, whatever causes the cooling.

Rising air expands and thus cools. Air sitting on a cooling surface will also cool.

In both cases condensation will start when that air passes its dew point.

Thank you Willis,

I re-read those 2 essays and still seek to explore – not the mechnisms that you describe as governing the control of conditions, which you have done explicitly well, but more how they know when to stop. As part of how they stop, overshoot or not, I use a set point analogy. So my questions have been about comparator mechanisms rather than mechanisms for change. IMHO, your hypotheses would be stronger if you could show a somewhat constant natural feature that is the “set point”that tells corrective processes when to stop. In tropical oceans that seldom have SST above 30C (I used 27C earlier, too approximate) what tells the systems that 30C has been exceeded and the process needs to stop? There might not be a set point. The foot on the throttle might be pressed to the floor the whole time, setting a limit that cannot be exceeded. Or, some part of the control system might become saturated, and not to be exceeded, perhaps part of cloud nucleation processes, but I am guessing here. The critical control might not even involve temperature centrally or at all, but as you know, climate research fixated on temperature from early in its emergence.

As I say, no sniping here, just trying to poke at ways to advance the narrative. Geoff S

Thanks, Geoff. I don’t know the answer to your question except to say that flow systems far from equilibrium are governed by the Constructal Law, and as a result they are generally running “as fast as they can” given the boundary conditions.

However, how that might play out mathematically is an open question.

w.

Have to model it so it can be called science.

That’s the way, climate science goes ! 😀

Not quoting any particular part of this well-written article, but I do have a bone to pick with the modelers in general. It is well known that 95+% of the annual emission of CO2 is entirely natural. Man’s contribution is less than 5%. By what stretch of the imagination, then, do modelers glom onto a doubling of CO2 in their models? No WONDER they are all wrong – it is not POSSIBLE for humans to cause the annual CO2 emission to double. Note, of course, that the earth absorbs virtually all of what it emitted during the year, so we are left, at most, with the less than 5% that is human contributed, assuming earth ‘ignores’ that. We should all realize, that if ALL human-oriented emissions of CO2 were stopped in their tracks, it would probably not be measurable. So, given that, let’s spend trillions of dollars to reduce our ‘carbon’ footprint to some arbitrary previous year? Doesn’t ANYONE see that reducing emissions to the level of some previous year would be immeasurable in the scheme of things. The earth is gonna do its thing each year, whether humans are even here or not. Always has.

To that, add that the 5% human contributions (20 ppm) is ‘blamed’ for all the earth’s weather and climate ills. Really? 20 ppm? Doesn’t ANYONE have a sense of scale?

If you calculate all burnt fossil fuel burnt since WW II it will come up to an addition of 200 ppm CO2 to the atmosphere. Luckily, the ocean and biosphere have used about half of it for greening the earth. So we left about 100 ppm to the atmosphere, rising the concentration from 300 to about 400 ppm. I do not know where your 20 ppm number is from.

Yes, the biosphere adds much more CO2 to the atmosphere as we human in the autumn, but it uses it again in the spring. So that’s a nullsummenspiel.

It is a big deal that different climate regimes rule at different latitudes. For instance, we have the interesting fact that the tropics are warmer than the equator. link Evaporation and convection remove a pile of heat from the equator. Rain removes the water from the convected air in the upper atmosphere. Radiation to outer space removes a lot of heat. The convected dried air descends on the tropics. Because it’s lost most of its moisture, its heat content is lower than when it went up but as it comes down it gains temperature (but not BTUs) as it compresses. Thus the tropics, where the convected air descends, are pretty hot.

The atmosphere is full of interesting and local processes. Most published work tends to treat the planet as a homogeneous whole. That causes a bunch of clueless, pointless arguments about that homogeneous whole which actually doesn’t exist.

I read your thermostat hypothesis essay, all those eleven years ago, and found it elegant — even though my own understanding of our atmosphere was very young and highly unskilled. It just felt right.

It still does. I am extremely grateful for this further exploration. Impressive reasoning sir.

Willis,

Another excellent post.

I would recommend that this post should be read in conjunction with your previous post of December 26: ‘A Decided Lack Of Equilibrium, Willis Eschenbach’

In the post of December 26, you showed that climate sensitivity, to increased TOA radiation, decreases with increasing temperature, and that feedback becomes negative, over water at temperatures above freezing, and over land at temperatures above about 10 C (Figure 5 from Dec. 26). In this post you have presented the mechanism for this behavior.

As I stated in a comment on Dec. 26, the above phenomena can be readily explained by the properties of water.

1. The partial pressure of water vapor increases exponentially with temperature. Thus evaporative cooling also increases exponentially with temperature. As you note in the text: ‘Not only that, but the minimum amount of annual rainfall increases smoothly and exponentially as the average sea surface temperature goes up’.

2. Water vapor is about 35% less dense than air. As density differences drive convection, the driving force for atmospheric convection increases linearly with the amount of water evaporation, and thus exponentially with temperature.

Your two posts show convincingly how the earth’s water-based biosphere provides a self-regulating mechanism that prevents the earth’s climate from deviating beyond a narrow range, and why the ‘global warming consensus’ is wrong.

We flew down to central South Carolina for the total solar eclipse August 21, 2017. It was a typical very hot August day with cumulus covering about 70% of the sky. Other than the eclipse, the most remarkable thing to me was the clouds just disappeared in about 20 minutes as the eclipse started.. absolutely gone.

Even though it was late afternoon, within 15 minutes after the eclipse, they started reforming. I would not have thought cloud formation was that sensitive to the energy being fed into the system.

I find the studies of clouds fascinating. It’s a shame they are ignored because clouds disrupt and invalidate the “CO2 drives temperature” theology. It is a travesty that we have spent so much money on fake climate science and in so doing have lost knowledge and become more ignorant, not less sbout our climate, not to mention all of the horrible harm we have caused to people and Earth and its beauty, animals, birds, insects and biosystems with windmills, solar arrays, biofuels and biomass.

The IPCC itself acknowledges that GCMs can’t actually model clouds, so they’re “parameterized”. That means their effects can be whatever the Planet GIGO computer gamers want or need them to be.

It also means we reduce our knowledge.

_______

97% of climate experts do not understand just how large an issue clouds are for modelers.

Very nice!

During various debates about Lord Monckton’s modifications to the feedback forcing model, the “stability” of the overall climate system got side-swiped on numerous occasions. The feedback, transfer function modelling has no inherent stability but such was implicitly assumed (i.e.: the 1850 base signal was still relevant 170 years on). The attraction to that assumption is due to the observed resilience of the climate in face of perturbations.

This work provides some real chew on why that assumption could be defensible. That is most useful.

The works goes much farther. The postulated decoupling of the heat/humidity cooling effect (via precipitation) from the feedback/forcing mechanisms is very clarifying. One can then make the comparison of the water vapor GHG vs. the CO2 GHG contributions as Willis has shown.

I have to then ask if the solar contribution in Lord Monckton’s model could be similarly decoupled. His work makes a similar comparison of contributions with CO2 forcing getting the short end of that stick. The climate models start-out at dubious and quickly descend towards appalling. Why try to fix stupid?

Instead, decouple solar radiance and water vapor effects and let CO2 GHG stand alone in comparison of their potential magnitudes. Why try to sort-out the mess and make them work together in an attempt to calculate some “equilibrium” temperature. The earth doesn’t have one, it has a steady-state with a central value it’ll chase as all the heat/wind/ice/water vapor engines tussle along.

Pedalling around Singapore dockyard many years ago with one’s Wanchai Burberry one recognised the hotter the day the earlier the inevitable thunderous downpour and temperature relief.

Great post

Good information

Thank you Willis

Of course you have a lot of personal experience with these phenomena having been a seafaring tropics man for so long.

Rain dries the air…whodda thunk it?

Willis:

That was a very quick eleven years!

Your revisiting the topic is timely and excellent!

Joe Bastardi published this link earlier today:https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/full/10.1175/BAMS-D-16-0116.1

Included within is this:

Willis, a very interesting article.

But just so’s I can claim to be consistent, what would you offer as the null hypothesis on this, as I’ve asked Messers Stokes and Mosher for on another post here.

Ta.

I’d say that the null hypothesis would be that there are no constraints on temperatures, that the conventional theory that ∆T = λ ∆F.

w.

That’s all Greek to me Willis 🙂

“the earth’s temperature has stayed in a surprisingly narrow range, e.g. ± 0.3°C over the entire 20th Century. ”

This describes my problem with “Climate Change.”

I have an expensive microprocessor controlled thermostat controlling my Heat pump. I also have a home weather station which keeps track of both indoor and outdoor parameters. A review of the data that this system provides indicates that the “state-of-the-art” thermostat can not keep my well insulated home [with all windows on the south side using solar shielding,] within +/- 1 degree F during one single day/24 hour period. Makes no difference if Summer, Winter, Fall, or Spring, It just can not keep the temperature within one degree of the setpoint. {This fact gives me concerns of these new regulations on insulation and sealing requirements of homes.] And I live in a ranch house! For a less than 1 degree F change of the “Global Average Temperature” [whatever that is] over 100 years convinces me that there is no statistically significant “Climate Change.” I sincerely believe that if all UHI temperatures were removed from the data creating this Global Average Temperature, that the actual increase in temperature would be farr less. Why has no one done this simple exercise?

My forced air heating system keeps the thermostat within +/- 0.5 F. Anywhere else in the house is a different kettle of fish. 🙂

Tony Heller has a great video on this: “How Homogenization Destroys Climate Science”

@Uzerbrain

The sun is constantly shining on the earth, hence the relatively stable global mean. Is the sun constantly shining on your house?

BTW, the global mean temperature varies MUCH more than Willis says, about 2.3 C (4 F) every year.

Snape January 7, 2020 at 8:26 pm

Huh? The sun doesn’t shine “constantly” on either one. The amount of sunlight hitting the surface is controlled by the clouds, which change constantly. There is no reason to assume a priori that those changes would average out in such a way that the global mean temperature would be stable.

Snape, in these kinds of discussions, the seasonal changes are generally subtracted out. If they weren’t the underlying changes would be much harder to see or understand.

Best to you,

w.

@Willis

The sun is constantly shining on the earth SYSTEM. I thought that was a given.

*****

We need to use anomalies where appropriate, not as a generic rule.

There is little change in the GM temperature anomaly from, for example, from one aphelion to the next….. because there is very little change in radiative forcing from one aphelion to the next.

When there IS a large change in radiative forcing, there IS a large change in temperature.

Not just aphelion to perihelion, of course. Volcanic eruptions, changes in albedo, Milankovitch cycles… all these have produced large changes in radiative forcing, and consequently large changes in global temperature.

This simple fact debunks the “thermostat” hypothesis.

*******

Note: Global land areas, on average, receive the most radiative forcing during aphelion. The land heats up very quickly and the atmosphere responds in kind.

The global oceans get warmer during the perihelion, when the sun is closest, but not fast enough to make up for the more rapid land area cooling.

Snape January 8, 2020 at 12:35 am

Thanks, Snape, but that’s not necessarily true. See below for a discussion of volcanoes.

Regards,

w.

Overshoot and Undershoot 2010-11-29

Today I thought I’d discuss my research into what is put forward as one of the key pieces of evidence that GCMs (global climate models) are able to accurately reproduce the climate. This is the claim that the GCMs are able to reproduce the effects of volcanoes on the climate.…

Prediction is hard, especially of the future. 2010-12-29

[UPDATE]: I have added a discussion of the size of the model error at the end of this post. Over at Judith Curry’s climate blog, the NASA climate scientist Dr. Andrew Lacis has been providing some comments. He was asked: Please provide 5- 10 recent ‘proof points’ which you would…

Volcanic Disruptions 2012-03-16

The claim is often made that volcanoes support the theory that forcing rules temperature. The aerosols from the eruptions are injected into the stratosphere. This reflects additional sunlight, and cuts the amount of sunshine that strikes the surface. As a result of this reduction in forcing, the biggest volcanic eruptions…

Dronning Maud Meets the Little Ice Age 2012-04-13

I have to learn to keep my blood pressure down … this new paper, “Abrupt onset of the Little Ice Age triggered by volcanism and sustained by sea-ice/ocean feedbacks“, hereinafter M2012, has me shaking my head. It has gotten favorable reports in the scientific blogs … I don’t see it at…

Missing the Missing Summer 2012-04-15

Since I was a kid I’ve been reading stories about “The Year Without A Summer”. This was the summer of 1816, one year after the great eruption of the Tambora volcano in Indonesia. The Tambora eruption, in April of 1815, was so huge it could be heard from 2,600 km…

New Data, Old Claims About Volcanoes 2012-07-30

Richard Muller and the good folks over at the Berkeley Earth Surface Temperature (BEST) project have released their temperature analysis back to 1750, and are making their usual unsupportable claims. I don’t mean his risible statements that the temperature changes are due to CO2 because the curves look alike—that joke has…

BEST, Volcanoes and Climate Sensitivity 2012-08-13

I’ve argued in a variety of posts that the usual canonical estimate of climate sensitivity, which is 3°C of warming for a doubling of CO2, is an order of magnitude too large. Today, at the urging of Steven Mosher in a thread on Lucia Liljegren’s excellent blog “The Blackboard”, I’ve…

Volcanic Corroboration 2012-09-10

Back in 2010, I wrote a post called “Prediction is hard, especially of the future“. It turned out to be the first of a series of posts that I ended up writing on the inability of climate models to successfully replicate the effects of volcanoes. It was an investigation occasioned…

Volcanoes: Active, Inactive, and Retroactive 2013-05-22

Anthony put up a post titled “Why the new Otto et al climate sensitivity paper is important – it’s a sea change for some IPCC authors” The paper in question is “Energy budget constraints on climate response” (free registration required), supplementary online information (SOI) here, by Otto et alia, sixteen…

Stacked Volcanoes Falsify Models 2013-05-25

Well, this has been a circuitous journey. I started out to research volcanoes. First I got distracted by the question of model sensitivity, as I described in Model Climate Sensitivity Calculated Directly From Model Results. Then I was diverted by the question of smoothing of the Otto data, as I reported…

The Eruption Over the IPCC AR5 2013-09-22

In the leaked version of the upcoming United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (UN IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) Chapter 1, we find the following claims regarding volcanoes. The forcing from stratospheric volcanic aerosols can have a large impact on the climate for some years after volcanic eruptions. Several…

Volcanoes Erupt Again 2014-02-24

I see that Susan Solomon and her climate police have rounded up the usual suspects, which in this case are volcanic eruptions, in their desperation to explain the so-called “pause” in global warming that’s stretching towards two decades now. Their problem is that for a long while the climate alarmists…

Eruptions and Ocean Heat Content 2014-04-06

I was out trolling for science the other day at the AGW Observer site. It’s a great place, they list lots and lots of science including the good, the bad, and the ugly, like for example all the references from the UN IPCC AR5. The beauty part is that the…

Volcanoes and Drought In Asia 2014-08-09

There’s a recent study in AGU Atmospheres entitled “Proxy evidence for China’s monsoon precipitation response to volcanic aerosols over the past seven centuries”, by Zhou et al, paywalled here. The study was highlighted by Anthony here. It makes the claim that volcanic eruptions cause droughts in China. Is this possible?…

Get Laki, Get Unlaki 2014-11-18

Well, we haven’t had a game of “Spot The Volcano” in a while, so I thought I’d take a look at what is likely the earliest volcanic eruption for which we have actual temperature records. This was the eruption of the Icelandic volcano Laki in June of 1783. It is claimed to…

Volcanoes Once Again, Again 2015-01-09

[also, see update at the end of the post] Anthony recently highlighted a couple of new papers claiming to explain the current plateau in global warming. This time, it’s volcanoes, but the claim this time is that it’s not the big volcanoes. It’s the small volcanoes. The studies both seem to…

Volcanic Legends Keep Erupting 2015-07-22

Once again, Anthony has highlighted a paper claiming that volcanoes have great power over the global temperature. Indeed, they go so far as to say: “From the reconstruction it can be seen that large eruptions, such as Mount Tambora in 1815, or clusters of eruptions, may …

Why Volcanoes Dont Matter Much 2015-07-29

The word “forcing” is what is called a “term of art” in climate science. A term of art means a word that is used in a special or unusual sense in a particular field of science or other activity. This unusual meaning for the word may or may not be …

Just to be clear about the anomaly issue:

If, say, the average GM of 30 aphelions is 19.0 C, and this year at aphelion the GM was 19.3 C, then this represents an anomaly of + 0.3 C

If, say, the average GM of 30 perihelions is 17.0 C, and this year at perihelion the GM was 17.3 C, then this represents an anomaly of + 0.3 C

In the above example, there was no change in anomaly from aphelion to perihelion. There WAS, however, a change in temperature. And this change in temperature was the result of changes in radiative forcing.

Snape, it appears you missed my comment above.

Best regards,

w.

Very interesting data presentation Willis. Weather as a surface cooling mechanism. Why are we surprised, convection was always a two-way vertical process. Nice to see the character of it confirmed in data and the result visualized within a 3D physics depiction.

Thanks to Willis for this important post. You can easily see the temperature changes caused by clouds in GOES-=16 lower and middle troposphere imagery. For initial viewing, select the full Earth view and look at the southern hemisphere where summer is occurring. For example, this selection clearly shows major cooling across most of Brazil caused by abundant cumulus clouds:

https://rammb-slider.cira.colostate.edu/?sat=goes-16&z=1&im=12&ts=1&st=0&et=0&speed=130&motion=loop&map=1&lat=0&opacity%5B0%5D=1&hidden%5B0%5D=0&pause=0&slider=-1&hide_controls=0&mouse_draw=0&follow_feature=0&follow_hide=0&s=rammb-slider&sec=full_disk&p%5B0%5D=band_09&x=12344&y=15048

The fourth transition brought to mind Frost’s; ‘The line-storm clouds fly tattered and swift’

Nice, thanks.

w.