by Judith Curry and Jim Johnstone

CFAN’s 2019 ENSO forecast is for a transition away from El Niño conditions as the summer progresses. The forecast for Sept-Oct-Nov 2019 calls for 60% probability of ENSO neutral conditions, with 40% probability of weak El Niño conditions. – Forecast issued 3/25/19

Introduction

CFAN’s early season ENSO forecast is motivated by preparing our seasonal forecast for Atlantic hurricane activity. ENSO forecasts made in spring have traditionally had very low skill owing to the ENSO ‘spring predictability barrier.’

During fall 2018, there was warming in the Central Equatorial Pacific, leading to a weak El Niño Modoki pattern, which impacted the latter part of the Atlantic hurricane season. This transitioned to a weak (conventional) El Niño in February 2019 and the atmospheric anomalies became more consistent with a conventional El Niño pattern.

NOAA’s latest forecast: Weak El Niño conditions are likely to continue through the Northern Hemisphere spring 2019 (~80% chance) and summer (~60% chance).

CFAN’s ENSO forecast analysis is guided by the ECMWF SEAS5 seasonal forecast system and a newly developed statistical forecast scheme based on global climate dynamics analysis.

ENSO statistics

Figure 1 illustrates the recent ENSO history as depicted by monthly Niño 3.4 anomalies from 1980 to February 2019. Highlighted are 20 El Niño Februaries (Niño 3.4 > 0°C), including the most recent (+0.5°C) in February 2019. The Niño 3.4 anomalies surrounding each February El Niño event are plotted in Figure 2, showing the index evolution from the previous July to the following December. The February events that are followed by December El Niño conditions (El Niño persistence) are plotted in red, while those events that reverse to December La Niña conditions are plotted in blue. The Niño 3.4 evolution of 2018-2019 is shown with heavy black markers.

ENSO behavior in late 2018 is remarkable for a steep increase from slightly negative Niño 3.4 SST anomalies in July to moderately positive anomalies (+1 °C) by October. Typically, fall El Niño intensification occurs with the growth of high-amplitude events that peak around +2°C before undergoing major reversals to La Niña throughout the following calendar year (blue lines in Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Time series of the monthly Niño 3.4 SST index (5°N-5°S, 170°-120°W), with warm February El Niño anomalies (<0°C) highlighted by red markers.

Figure 2. Seasonal Niño 3.4 SST anomalies surrounding February El Niño conditions (Niño 3.4 SST anomaly > 0). A. Lines trace monthly Niño 3.4 SST anomalies from July (year -1) to December (year 0) f for all February (year 0) El Niños. Lines are colored according the sign of December (year 0) Niño 3.4 SST anomalies, with December El Niños plotted in red and La Niña in blue.

ENSO forecasts from global models

The IRI/CPC plume of model ENSO predictions from mid-March 2018 is shown in Figure 1. The latest official CPC/IRI outlook (Figure 2) calls for a 80% chance of El Niño prevailing during Mar-May, decreasing to 60% for Jun-Aug.

Figure 1. https://iri.columbia.edu/our-expertise/climate/forecasts/enso/current/

Figure 2. The official CPC/IRI outlook, with an El Niño advisory, calls for a 80% chance of El Niño prevailing during Mar-May, decreasing to 60% for Jun-Aug. https://iri.columbia.edu/our-expertise/climate/forecasts/enso/current/

CFAN’s ENSO forecast plumes from ECMWF (initialized March 1) are shown in Figure 3, for Niño1.2, Niño 3, Niño4, and the Modoki Index. ECMWF shows a peak of Niño 3 in May 2019 and a peak in Niño 1.2 in April, with subsequent declining values. Niño 4 values peak in June, and there is a hint of a return to Modoki (> 0.5) by September.

Figure 3: CFAN’s analysis of ENSO forecasts from ECMWF SEAS5, initialized 3/1/19.

Figure 3: CFAN’s analysis of ENSO forecasts from ECMWF SEAS5, initialized 3/1/19.

CFAN’s analysis of the ENSO hindcast skill of the ECMWF SEAS5 seasonal forecast model (Figure 4) shows a correlation coefficient of 0.7 for Niño3 and 0.79 for Niño4 forecasts initialized in March for a seven month forecast horizon (September). For a forecast initialized on March 1, Nino4 shows greater predictability than Nino4 for a 6-7 month forecast horizon.

Figure 4: Evaluation of the predictability of the Niño 3 and Niño 4: correlation of observed versus predicted) from ECMWF SEAS5 as a function of initial month and lead-time. From Hirata, Toma and Webster, 2018: Updated quantification of ENSO influence on the U.S. surface climate. https://ams.confex.com/ams/98Annual/webprogram/Paper334884.html

ENSO statistical forecast model

Figure 5 shows the global sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies for January through February, 2019. Recent anomalies in the tropical Pacific reflect El Niño conditions (Niño 3.4 SST anomaly +0.5°C), with greatest local warmth evident in the equatorial central Pacific.

Two methods were used to forecast the seasonal anomalies and evolution of tropical Pacific SSTs during 2019. Niño 3.4 index anomalies (Figure 6) were forecast on the basis of recent February-March atmosphere-ocean anomalies and tendencies that systematically correlate with later ENSO anomalies. Climate precursors were identified in globally-gridded variables in the NCEP-NCAR Reanalysis at 17 vertical levels from the surface to the stratosphere. Additionally, we forecast full global SST fields (Figure 7) with a similar scheme based on the 4 leading Principal Components of global SST variability in each season. Both methods give similar forecasts of ENSO conditions throughout 2019.

Figure 5. Observed global sea surface temperature anomalies for the period Jan-Feb 2019

Figure 6. Statistical model projections of Niño 3.4 SST in three-month windows from March to December 2019. Black markers show estimates obtained from ensembles of 20 forecast models, with final forecasts indicated by ensemble means in red markers.

Figure 7. Statistical model projections of global sea surface temperatures in three monthly increments through November 2019.

Spring forecasts reflect persistence of current moderate El Niño conditions (Niño 3.4 ~ +0.5), and a gradual decay to near-neutral, slightly positive anomalies (+ 0.1 °C) by mid-summer (July-August-September). Spatial SST forecasts in Figure 7 suggest more rapid cooling in the tropical SE Pacific than in the NE Pacific. July-August-September SST anomalies are somewhat greater in the central equatorial Pacific than in the far east, suggesting an El Niño Modoki signature. From late summer to fall, models project a re-emergence toward typical El Niño conditions, charactetrzed by warming throughout the east-central equatorial Pacific to an October-November-December anomaly of +0.4°C.

Typo in Figure 1. explanation. Should say anomalies (>0 C) highlighted in red, not (<0 C).

So, it doesn’t look like we can predict ENSO oscillations even a year out very well. What was that about settled science?

Hi Jeff

Without understanding the cause any prediction has no value. When we know more about the cycles of the equatorial Pacific’s tectonic activity, the science might have chance to get there.

http://www.vukcevic.co.uk/ENSO.htm

(the cumulative SOI delay of about 12 years might be related to the solar polarity change or 11.86 years orbital periodicity)

Vuk

I definitely cannot agree with your opening statement. Any reliable prediction has value when it comes to the weather. Any engineering prediction that gives a three nines answer is useful and one and a half nines was used for decades.

The “rules of thumb” used in the first century of the industrial age were giving useful answers even when the properties of materials were substantially unknown.

Consider the difference between a simplified deflection formula that gave an answer within 2 or 3% of the real value, and the hopeless climate models which, the modellers claim, are based on well-understood mechanisms. All that “science” stuff they go on about. If the understanding is so good why are the results so bad?

At the least we have to characterise sets of systems and their relative ability to give a “right answer”. I have followed many of your detailed explanations and am impressed with your ability to get a ” pretty good answer” with no clear idea about the underlying mechanisms. Nothing wrong with that!

It is sort of like being able to sing beautifully and not being able to read music. I don’t care, only listen and applaud.

Carry on carrying on.

Well that El Nino didn’t really get going at all. Would love to know if this is linked to the solar minimum?

“Well that El Nino didn’t really get going at all”

I wouldn’t write it off yet. The plot of Nino 3.4 shown here ends in February. It rose 0.3°C in March. Global temperatures rose 0.2°C, and April so far is even warmer.

The solar minimum indicates there should be a Niño at this time, as I predicted last July.

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2018/07/05/solar-minimum-and-enso-prediction/

The strength of the Niño likely depends on the conditions, the amount of subsurface heat accumulated at the time it starts, how long since a strong El Niño, how long since a strong La Niña. ENSO is a capacitator that recharges heat during Neutral and La Niña conditions and discharges it during Niños.

A La Niña is expected in late 2020-2021 and conditions suggest it could be a two-year Niña.

So if we go by their past accuracy in forecasting ENSO, then this forecast means it will either be a strong El Nino or a strong La Nina !!!!

…like the NHC on hurricane predictions

start out high..because their computers say global warming causes more and stronger

….slowly downgrade each month

…and at the end claim accuracy

About 3 weeks ago some anomalously cool water started to upwell near Central America and has subsequently grown larger. It already appears to be cooling the Nino 3 region and the tradewinds are back to being strong.

Yeah, I’ve seen that — quite odd. If you looked at the below site it showed strong north to northeast winds right in those cool spots, so presumably those winds caused extensive upwelling of the cool water there.

http://cci-reanalyzer.org/wx/DailySummary/#T2

Nino1.2 does tend to be the starting point, though Nino3.4 seems to be the reference for supposed lagged- correlation with other parts of the world.

Anyone looking to forecast should probably be studying Nino1 and 2.

Yes Robert, this looks like it could be very interesting. This cool water is mixing with the upwelling warm water and starting to produce neutral conditions. If this keeps up then I expect to see an ENSO neutral summer.

There was that cold tongue over the Galapagos just before I got there for a week. Otherwise it would have been warmer. I got to see a little rain only once, over night, and mostly sunny conditions from Mar 24 thru 28th

Looking at figure 2, we can say with complete confidence that the Nino 3.4 sea surface temperatures will be going down for the rest of the year…or up…or stay the same.

Actually, the only thing we can say with scientific confidence is that we have very little confidence in our ability to predict ENSO conditions very far in advance. Of course, it is important to make forecasts in order to test our ideas about ENSO, and gradually improve our scientific understanding. It would just be foolish to be implementing sweeping policy changes based on forecasts that have shown very little skill.

Um…wait a minute!

My bet is that temperatures wiil be bang on long term averages.

what leads you to base your expectations on the expectation value of the existing data ? 😉

Using NOAA Criteria, a full-fledged El Nino 2018-19 event has already begun at the end of March 2019 since five consecutive overlapping 3-monthly seasons have had ONI of greater than or equal to +0.5ºC. Last five ONI Index are SON 2018 +0.7ºC, OND 2018 +0.9ºC, NDJ 2019 +0.8ºC, DJF 2019 +0.8ºC and JFM 2019 +0.8ºC

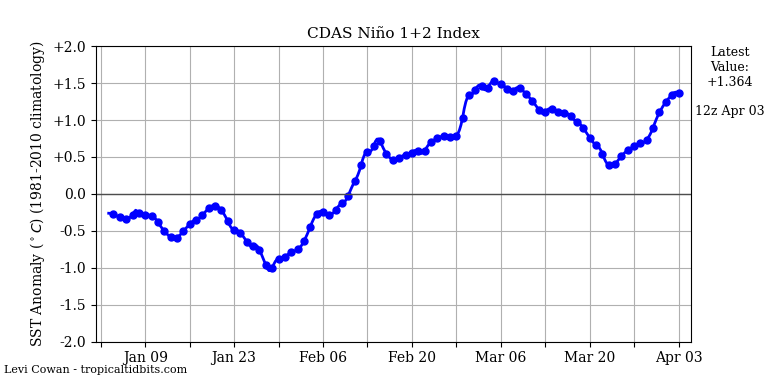

A weak El Nino has already begun but with a difference. The Atmospheric connection is missing. latest 30 days average SOI is just -1.68 from The Long Paddock, Queensland. The Nino 1+2 regions are cooler than normal. See image

Wiggle watching… with very little wiggling.

This makes oil price forecasting look good.

“The forecast for Sept-Oct-Nov 2019 calls for 60% probability of ENSO neutral conditions…”

ENSO neutral conditions in the fall will increase the Atlantic Basin Hurricane numbers/intensity over the current forecast of slightly below normal 2019 hurricane season.

Dangerous weather.

http://oi68.tinypic.com/ka2r9g.jpg

Hi, most will have noticed the recent upturn in Tahiti surface pressure ( last week or so)-

https://www.longpaddock.qld.gov.au/soi/

This seems to be associated with the formation of a surface wind current through the middle of the pacific! From an antarctic low via a central pacific high and over Tahiti and from there over the western equatorial pacific.

https://earth.nullschool.net/#current/wind/surface/level/orthographic=-142.92,-27.65,640

This may be nothing more than coincidence but I haven’t thought to look at this area of the pacific before for changes in ENSO. I will be watching this area more carefully in the future.

A little puzzled- bruce

The SOI is based on the atmospheric pressure comparison between Tahiti and Darwin. That is what drives strength and direction of the trade winds. Does that help out?

I highly recommend Bob Tisdale’s book to help understand ocean cycles

Hi Pop Piasa,I’m know what the SOI is, also Kelvin waves, counter currents, reversal of trades in the west pacific, ocean height anomalies etc. I didn’t realise the possibility that the strenght of the trades in the western pacific could (maybe) be directly affected by antarctic pressures via the central Pacific route- I had assumed this occured up the western coast of South America.

I know I should read Bobs book, but haven’t got around to it yet– thanks for your reply

When the ENSO forecast made by the Japanese Met Agency moves 50 % El Nino vs. 50 % neutral, then I will start to think about this actual El Nino starting to weaken.

http://ds.data.jma.go.jp/tcc/tcc/products/elnino/elmonout.html#fig2

But not before. Simply because I watch this page since quite a long time, and JMA’s predictions were all the time the best ones.

I like this analog prediction.

https://www.oregon.gov/oda/programs/naturalresources/documents/weather/dlongrange.pdf

Pamela Gray

An interesting document. I appreciated.

Thx for the link.

J.-P. D.

Someone should tell them that there is no such thing as Seasonal Climate Forecast. If one is forecasting the next season, one is forecasting weather, not climate.

Preserving continuity from 2018, when I said:

(1) Last Oct, ‘We are closer to both the solar and ENSO 2006 analog year.’ ENSO & analog years.

(2) In Nov, “I expect the ENSO situation to go the other way early next spring, with a small short LaNina-ish dip such as HadSST3 exhibited in 2007, before rebounding into what I call a ‘solar cycle onset ENSO’.”

Pacific Ocean Equatorial anomaly for this year is encouraging evidence for (2) LaNina-ish development.

Right now the main uncertainty is whether or not solar activity will increase this year and turn this mild El Nino into a raging monster, breaking the recent solar minimum analog pattern, or will it stay low and break the solar cycle 18-23 post 72 sfu pattern described next…

If SC24 hasn’t already reached it’s minimum, this month will break the SC18-23 solar minimum 5-14 month window (see prior image) for duration to the minimum after the first 3-month average of adjusted F10.7cm under 72 sfu.

The list of minimums in v2 sunspots, in months after the start of the first three month average of under 20 sunspots:

SC23 22

SC24 23

SC14 33

SC12 34

SC6 32

SC5 36

So solar cycle 24 could in theory last another 9-13 months, which would put my expected solar cycle onset ENSO into the 2020 time frame instead of 2019, while also preserving previous ENSO patterns.

No matter what it’s going to be interesting, and hopefully as clear-cut as the last minimum.

Corrections: This should be ‘recent solar minimum ENSO analog pattern’, and it’s link was meant for ‘post 72 sfu’; and ‘The list of the longest minimums’…

Even though this solar cycle was historically low early, currently at 124 months long it still hasn’t reached the average length of the 24 counted cycles, 132, and is low on the ranks of length, with 15 cycles above it that averaged 140 months, 164 max.