Alternative title: “Standing on the shoulders of Giant Bob”

Guest post by Phil Salmon

Introduction

One of the themes to emerge from the climate debate here on WUWT, concerns “chaos” and nonlinear system dynamics and pattern. Anyone acquainted at all with the nature of dynamical chaos and nonlinear / non-equilibrium pattern formation, and who also has an interest in the scientific questions about climate, cannot fail to sense that dynamical chaos has to be an important player in climate. Simply on account of the huge complexity of climate over the expanse of earth’s surface and deep time, and also the obvious impossibility of equilibrium in a rotating system with continuous substantial imbalances of heat and kinetic energy.

However, a “sense” is hardly adequate scientifically; it is necessary to go further than this and forge some kind of physical and mathematical model or hypothesis which can be tested. But here one runs into the problem of chaotic systems being .. well, chaotic and unpredictable; indeed for some the movement of a system into the chaotic region represents falling off the edge of the world of scientific testability and orthodox Popperian experimental investigation. Is it a contradiction in terms to imagine that you can study chaos scientifically and mathematically? The scientific community at large – not only climate science – while giving lip service to chaotic pattern formation as a real phenomenon, generally shrinks back from serious engagement with it, back into the comfortable regions of tidy linear and equilibrium equations.

However there does exist a well-established science of physical and mathematical study of chaotic, nonlinear systems, in which a wide range of nonlinear pattern forming systems are well understood and characterized. But owing to the human tendency to associate in closed communities – nowhere more in evidence than in the multi-faceted scientific world, there is in my view too little engagement between the chaos and nonlinear dynamics experts and scientists in a wide range of natural sciences whose studied systems are – unknown to both sides – accurately and usefully characterized by well-researched nonlinear pattern systems.

It is the purpose of this article to propose a well-known experimental “nonlinear oscillator”, namely the Belousov-Zhabotinsky chemical reaction, as an analogy – in terms of its dynamics and spatio-temporal pattern – for the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) system in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. This would characterize and alternation between El Nino and La Nina as a nonlinear oscillator. The definitive work of Bob Tisdale on the ENSO is used to liken the alternating multi-decadal periods of eE Nino and La Nina dominance (the PDO) as the two wings of the Lorenz butterfly attractor.

The term “chaos”, while a common shorthand for a class of phenomena and systems, is not a very accurate or helpful one. Chaos itself, strictly speaking, is truly chaotic and not a very fruitful area of mathmatic investigation. A system passes from the region of linear dynamics through “fringes” or borderlands of mathematical bifurcation before reaching full blown chaos, and it is in these marginal and transitional borderlands where the interesting phenomena of strange attractors and spontaneous pattern formation arise. But it is hard to find a convenient single word that takes its place – it is easier to say “chaos” than “nonlinear pattern formation in far-from-equilibrium dissipative systems”.

Even “nonlinear”, while better than “chaos”, is still inadequate: there are plenty of physical and mathematical systems which are clearly not “linear” but not related to non-equilibrium emergent pattern formation. A relative of mine – a TV weatherman in Monterrey, California for many years before his retirement – pointed this out to me, that it is not necessary to invoke nonlinear pattern formation to account for acute sensitivity to initial conditions – a simple high power relationship is sufficient for this. Acute sensitivity to initial conditions does indeed characterize many nonlinear systems – indeed, one popular metaphor for chaotic systems is the “butterfly wing” effect – namely that a butterfly wing’s disturbance of the air in one place can result in massive changes in weather systems a continent away. The butterfly wing analogy was coined by Edward Lorenz – a pioneer in mathematical study of non-equilibrium pattern system and also a meteorologist – we will return to Lorenz later. However this sensitivity does not uniquely define the type of system we are considering. (The “butterfly wing” metaphor is now inseparable from the actor Jeff Goldblum and his rather inane use of the phrase in the Jurassic Park films.)

If I had to propose an alternative to “chaotic” as a general short term for such systems with spontaneous nonlinear pattern dynamics, I would go for something like “non-equilibrium pattern” systems.

One of the most helpful references I have found on the subject of non-equilibrium pattern systems is the PhD thesis of a chemical engineer Matthias Bertram, entitled “controlling turbulence and pattern formation in chemical reactions” – previously posted on his web site but now reposted on Google docs:

Matthias uses the term “pattern formation in dissipative systems”. To quote from the introduction of this thesis:

“The concepts of self-organization and dissipative structures go back to Schrodinger and Prigogine [1–3]. The spontaneous formation of spatio-temporal patterns can occur when a stationary state far from thermodynamic equilibrium is maintained through the dissipation of energy that is continuously fed into the system. While for closed systems the second law of thermodynamics requires relaxation to a state of maximal entropy, open systems are able to interchange matter and energy with their environment. By taking up energy of higher value (low entropy) and delivering energy of lower value (high entropy) they are able to export entropy, and thus to spontaneously develop structures characterized by a higher degree of order than present in the environment.”

The author goes on to analyze several experimental non-equilibrium pattern systems, including the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction. He outlines the essential conditions for the operation of a nonlinear oscillator such as a far from equilibrium state, and an “excitable medium”, that is, a medium within which localized positive feedbacks can be initiated and run their course according to their associated refractory period. We will return to these parameters when we consider the ENSO.

The Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction

There is a helpful short introduction to the Belousov-Zhabotinsky (“BZ”) reaction on Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belousov%E2%80%93Zhabotinsky_reaction

Have a look at this youtube video shown in figure 1:

Figure 1A. A video of the BZ nonlinear oscillation in a stirred beaker.

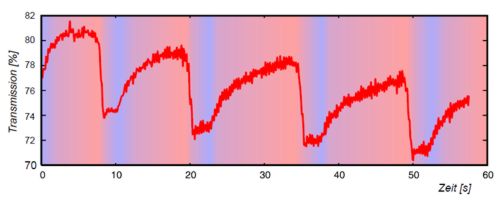

Figure 1B. A graph of light transmissivity over time, illustrating the BZ reaction (from Wikipedia DE)

What you are looking at is the Belousov-Zhabotinsky (BZ) reaction in a stirred beaker. It is striking in that the beaker’s liquid contents oscillate between a dark blue colour and clear transparency, for multiple cycles. Most of us can recall school chemistry lessons from the (more or less) distant past, where we saw reactions such as the titration of potassium permanganate with hydrogen peroxide, causing a beaker or tube full of liquid to change from dark purple color to clear, or vice versa. But not many of us probably saw the oscillating BZ reaction with a tube of liquid oscillating between the two starkly contrasting states. The BZ reaction “involves several reagents and various intermediate species; the central reaction step is the oxidation of malonic acid by bromate, catalyzed by metal ions” (Matthias Bertram 2002). The system is jumping between two states looking for equilibrium but finding it in neither.

This is intriguing to watch but what is going on here, and what significance does it have to climate, to the behavior of atmospheres and oceans?

The BZ reaction is a gateway to a whole branch of science which is, to repeat, still very incompletely explored and whose significance is under-appreciated. The two individuals, Boris Belousov and Anatol Zhabotinsky, who established their eponymous reaction, have an interesting history which has some resonance with the politics of climate science. Boris Belousov accidentally came across the oscillating reaction in Soviet Russia during the early 1950’s (one of the important and long undiscovered Soviet scientific discoveries that also included the “Ilissarov frame” orthopedic method for making new bone by gradual movement apart of fractured bone ends). Belousov’s attempts to publish this finding were rejected repeatedly, on the grounds of the familiar “where’s the mechanism?” argumentum ad ignorantium. In 1961 a graduate student Anatol Zhabotinsky took up and ran with the discovery, but it was not until an international conference in Prague in 1969 that the reaction became widely known, two decades after its inception.

The BZ reaction is a “reaction-diffusion system”. It is a non-equilibrium pattern phenomenon known as a nonlinear oscillator; there are certain prerequisites for such a system to develop:

- The system is far from equilibrium

- It is an open system with a flow through of energy (dissipative)

- The system has an “excitable” medium

The BZ reaction meets these requirements sufficiently to set off nonlinear oscillation. Note that condition 2 is only partly and temporarily met – a tube of chemicals is not really open; however the availability of reagents makes the system for a limited time behave like an open system until the reagents become exhausted.

The BZ reaction in a thin film

There are many types and flavours of the BZ reaction. In the first example we saw the reaction in a beaker: however when the reaction is carried out in a thin film, a new element arises: instead of the solution changing colour en-masse, the colour changes are associated with intricate evolving patterns such as radiating ripples and spirals.

You can search for “BZ reaction” on youtube and find many examples of attractive moving patterns, some with musical accompaniment. One of these is given in the link below:

Figure 2. Three animations of the BZ reaction in a thin film, showing evolving spatiotemporal waves and patterns and alternations of dominant colour phase.

This link presents three BZ thin film animations. In the first, regions of orange and pale blue colour repeatedly expand and contract, encroaching on each-other reciprocally, such that looking at the dish as a whole, the predominant colour alternates between orange and pale blue. The second animation is one where typical BZ fringe and spiral patterns in dark and light purple radiate from various centers. If you look in the bottom left corner, a tongue of darker purple periodically grows and recedes. The third animation is a slower moving version of the first – if you have the patience to watch all of it, again there is an overall pattern of alternation between orange and pale blue as the predominant colour.

Another youtube video of a thin film BZ reaction is given in the link below; while it is tediously slow and would have benefited from acceleration, it shows nicely the radiating BZ patterns characterized by alternation between orange and pale blue as the predominant color.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S20Jsfu9rkQ

Figure 3. Another animation of the BZ reaction in a thin film showing travelling patterns and alternating phases.

During some parts of these BZ sequences, especially of the first animation, you have the feeling that you could be watching one of Bob Tisdale’s animations of the temporal evolution of sea surface temperatures (SSTs), such as that occurring in the equatorial Pacific with alternating el Nino and La Nina cycles: such an animation is given (By Bob) in the link below:

Figure 4. An animation of sea surface temperature anomalies in the Pacific during the transition from el Nino to La Nina systems during 1997 – 1999 (from Bob Tisdale’s blogspot), from web page: http://bobtisdale.blogspot.com/2010/12/enso-related-variations-in-kuroshio.html

If one focuses on the south eastern Pacific off the Peruvian coast, where the alternating tongues of warm and cool surface water characterize respectively the alternating en Nino and La Nina, the analogy to the BZ reaction is particularly compelling.

The ENSO as a nonlinear oscillator?

However beyond an intriguing qualitative visual similarity, what basis is there for proposing that the ENSO could constitute the same type of nonlinear oscillator as the BZ reaction? Please note that I am not proposing that chemical reactions play a role in the ENSO – no, chemical potentials in the BZ reactor are matched by thermodynamic potentials in the atmosphere-ocean system. Specifically we can return to the question of the essential pre-requisites that the BZ system meets to operate as a nonlinear oscillator; how would the ENSO system also meet these pre-requisites?

1. A system far from equilibrium

At least this one is a no-brainer. Solar energy input is very unequally distributed on the earth’s surface, maximally at the equator and minimally at the poles. Add to this the rotation of the earth and associated day-night cycle, and oblique axis rotation causing reciprocal summer and winter in north and south hemispheres, and ocean circulation, and it soon becomes clear that equilibrium is never remotely approached. (In fact, a world with atmosphere, ocean and heat flux in equilibrium is a nightmare to contemplate, with stagnant anoxic seas and stale motionless air.)

2. An open, dissipative system

The global climate system is open, as it receives heat input from the sun which (Leif Svalgaard notwithstanding ) is subject to minor periodic fluctuation. Heat is also radiated out to space. Heat energy enters and leaves the system; thus it is dissipative.

3. A system with an excitable medium

This is perhaps the most critical requirement. “Excitable” implies that an induced change at one location sets in motion a positive feedback which results in local amplification and propagation of the induced change – for instance taking the form of a travelling wave in the BZ reaction. This is not a wave in the sense of an energy wave through water or air that merely transmits energy, but a wave in which a spreading reaction is stimulated generating new local energy with the propagating wave. A cascade of chemical reactions in the BZ reaction constitutes this excitability. This positive feedback is limited and runs its course – characterised by a refractory period – but its operation is sufficient to drive and sustain the nonlinear oscillation, and in some cases to generate complex spatiotemporal patterns.

How could such excitability exist in the equatorial Pacific where the ENSO takes place? To discuss this question I need to refer to an exchange I had a few months ago with Bob Tisdale on a thread here at WUWT. The topic was one of these chicken-and-egg discussions of what drives the ENSO, either top-down by trade winds for instance, or bottom up by variation in deep upwelling. I posed the question to (who better?) Bob Tisdale, suggesting that the spread of both the el Nino and the La Nina, could involve a time-limited positive feedback. The nature of these positive feedbacks is indicated in the two diagrams below.

Figure 5. The La Nina positive feedback: enhanced Peruvian cold upwelling sharpens the equatorial Pacific east-west pressure gradient, driving stronger trade winds which propel further upwelling.

Figure 6. The el Nino positive feedback: decreased upwelling weakens the trade winds which propel the upwelling.

Please note that in the schematic systems in figures 5 and 6 it is not really relevant which comes first – changes in the trade winds or in upwelling. They are linked in a feedback loop. The analogy that I had in mind was of the on-shore and off-shore breezes that occur in summer in temperate coastal locations such as the British Isles. Here, in the day, increasing land temperature warms the surface air, causing it to decrease in density and rise, drawing in on-shore winds from the sea. Conversely at night, the land temperature quickly cools, increasing surface air density such that the wind is reversed to an off-shore breeze. (By contrast the air temperature over the sea is relatively constant). It was this essential mechanism that I suggested for the equatorial Pacific ENSO system, that the upwelling off Peru associated with the start of a La Nina cycle, in cooling the east Pacific surface layer air, creates a higher air pressure or density to the east that acts to drive east-to-west (easterly) trade winds (of the type that propelled Thor Heyerdahl and his companions on their epic Peru to Indonesia crossing of the Pacific on their “Kon Tiki” balsa wood raft, recapitulating the voyages millennia earlier of Polynesian mariners and ocean island settlers). These energised trade winds will push Pacific surface equatorial water westwards, adding impetus to the Peruvian upwelling by drawing eastern Pacific deep water toward the surface in a conveyer-belt like fashion. Thus the full cycle of a positive feedback illustrated in figure 5.

Conversely, during an el Nino cycle, upwelling is slowed or interrupted, resulting proximally in increased solar heating of more static, less mixed surface water in the Pacific east. This will decrease the temperature and pressure east-west difference, sapping force from the trades and resulting in doldrum conditions of decreased winds. The weakened trades will then slow the upwelling conveyor, connecting a feedback cycle that moves toward interrupted upwelling and a rapid spread of warm surface water from the east Pacific (figure 6).

It was a big moment for me when Bob Tisdale replied to the affirmative, agreeing that a time-limited positive feedback did indeed drive the onset of el Nino and La Nina, until both ran their course, reaching, to quote the term Bob used, “saturation”. Of course the whole system involves more complexity than this idealised system – there are periods of neither el Nino nor La Nina, or of modified, “Modoki” el Nino systems. However for me Bob’s positive reply was very important because the final piece of the jigsaw for this BZ-reaction analogy fell into place. Now I had my excitable or reactive medium. So it began to become clearer that the ENSO can indeed be characterised as a nonlinear oscillator, analogous to the BZ reaction-diffusion system.

3. The attractors and longer term pattern of ENSO (the PDO)

A feature of non-equilibrium pattern systems and their spatio-temporal evolution is an attractor. An attractor is a subset of the (often multidimensional) phase space that characterises a system, towards which the evolving system state converges. When an attractor takes on a complex fractal form it becomes a “strange attractor”. The strangeness of attractors does not however mean that they are not well understood – on the contrary, many different classes of attractor have been identified and studied mathematically.

A somewhat dry and technical description of attractors is given in wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attractor

In the context of our analogy of the ENSO as a nonlinear oscillator, a particularly interesting type of nonlinear attractor is the Lorenz attractor. Figure 7 below shows the time plot of phase space displacement of a Roessler and a Lorenz attractor. In figure 8, the phase space trajectory plot is given for the two corresponding attractors. The Lorenz attractor displays phase space “tearing” into two separate domains, while the Roessler attractor is characterised by phase space folding. The bilaterally torn attractor is sometimes referred to as the Lorenz “butterfly”.

(The chaos butterfly is rehabilitated! Providing one understands that one is referring to the Lorenz butterfly attractor, not the spurious “butterfly wing” effect.)

Of course, the Lorenz and Roessler attractors are simple classic types of nonlinear attractor. The Lorenz attractor exhibits oscillation of a fractal nature on more than one scale: the fine scale oscillation itself oscillates over a longer time period between higher and lower values of the phase space parameter on the y axis. More complex versions of both attractors exist – and many further types also. Figure 9 shows two examples, a Roessler attractor which shows tearing like a Lorenz attractor, and a folded chaotic BZ reactor attractor which kind of looks like a cross between a Roessler and a Lorenz.

Figure 7. The time plot of phase space displacement of a Roessler and a Lorenz attractor.

Figure 7. The time plot of phase space displacement of a Roessler and a Lorenz attractor.

Figure 8A. The phase space trajectory plot of the Roessler attractor (folding)

Figure 8B the Lorenz attractor (tearing).

Figure 8B the Lorenz attractor (tearing).

Figure 9A. A half inverted torn chaos solution to a Roessler attractor

Figure 9A. A half inverted torn chaos solution to a Roessler attractor

Figure 9B. a folded chaotic BZ attractor.

Figure 9B. a folded chaotic BZ attractor.

A note on reading the literature on chaos and non-equilibrium pattern dynamics. Only pay minimal attention to the text and even less to the maths. Just look at the pictures. It is the spatiotemporal multidimensional patterns that are the unifying and compelling feature, and it is pattern analogies between disparate systems which reveal the unifying pattern processes at work. In the above figures I have not defined the parameters in the x and y axis – they don’t really matter.

The Lorenz attractor and the ENSO

Does the time plot of the Lorenz attractor in figure 7 (b), with its higher and lower frequency components, remind you of anything? The wavetrain appears to spend alternating periods oscillating in a higher and a lower region of the y axis. Here again our discussion turns to the definitive work by Bob Tisdale on the ENSO. Bob’s recent posting on WUWT (reposted from his own blogspot) entitled “Integrating ENSO: multidecadal changes in sea surface temperature” had the subtitle “Do multidecadal changes in the strength and frequency of el Nino and La Nina events cause global sea surface temperature anomalies to rise and fall over multidecadal periods?”. A link to this article (pdf) is:

This tour-de-force of the ENSO and its controlling influence on global SSTs demonstrated how, over the past century, there have been alternating periods of about three decades duration during which the el Nino and La Nina systems are reciprocally dominant. Two plots from Bob’s article are shown below in figure 10.

Figure 10a shows the ENSO oscillations exhibiting alternating periods of higher and lower elevation on the y axis (Nino SST 3.4 anomalies), although with far more noise than the tidier level-switching oscillation of the Lorenz attractor. The Nino 3.4 plot thus resembles a very untidy or chaotic Lorenz attractor time plot of the type shown in figure 7b. The alternating periods dominated by the el Nino (1910-1944, 1976-2009) and by La Nina (1945-1975) represent the two wings of the Lorenz butterfly. Thus this period-alternation between a generally warming el Nino dominated phase and a cooling La Nina dominated phase, fits in with the description of the ENSO system as a nonlinear oscillator, of the BZ reaction type, and characterised by a torn attractor of the Lorenz – or possibly modified torn Roessler – variety. It is also known as the Pacific decadal oscillation, or PDO.

Figure 10A. The Nino 3.4 SST anomalies from 1910 to the present, averaged into roughly 30 year periods by Bob Tisdale.

Figure 10B. Global SST compared to period-averaged Nino 3.4 anomaly. Both from “Multidecadal changes in sea surface temperature” by Bob Tisdale.

Is the PDO the Lorenz butterfly attractor of the ENSO?

Closely linked to the ENSO is the PDO – indeed Bob Tisdale asserts that the PDO is an epiphenomenon of the ENSO. His recent posting on multidecadal variation in SSTs elucidates this relationship, showing the PDO to essentially comprise alternating periods of el Nino and La Nina dominance. On the basis of the proposal presented here that the ENSO is a nonlinear oscillator, we can suggest further that the alternating “PDO” phases are the paired “butterfly wings” of a Lorenz attractor characterising the ENSO.

Figure 11. Could the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) represent the operation of a Lorenz “butterfly” torn attractor on the ENSO?

Periodic forcing of the ENSO nonlinear oscillator

At this point, some of you may be saying “hold on a moment – I’m not convinced by this BZ reaction analogy. Most of the BZ reactions (e.g. shown on youtube) show spiral and fringe patterns that are not at all persuasive analogies to the shifting regional patterns of ocean surface temperatures”. You would have a point. However it is necessary at this stage to introduce another class of nonlinear oscillators – the periodically forced nonlinear oscillator. The BZ reactions that were referred to above, and shown in the attached movies, are all unforced examples. These unforced BZ reactions oscillate and their own natural frequency, and are indeed often characterised by such radiating spiral and fringe patterns. But the spatiotemporal patterns can change profoundly when the BZ reaction is subject to periodic forcing. Figure 12, provided by Matthias Bertram’s PhD thesis, shows a series of spatial patterns from a BZ reaction which is catalysed by a light sensitive metal catalyst, then subject to various regimes of periodic forcing by light pulses. The first case (a) is unforced and looks like many of the youtube BZ reaction animations. However a wide range of different patterns is observed (b-g) when different periodic forcings are applied.

Figure 12. A BZ reaction with a light-sensitive metal catalyst, showing spatially extended nonlinear oscillator patterns. Case (a) is unforced; all the remaining are subject to different amplitudes and frequencies of light pulse periodic forcing. Taken from the PhD thesis of Matthias Bertram.

Anna Lin et al. (2004) looked further at the role of periodic forcing in the light-sensitive BZ reaction. The BZ system in the absence of forcing oscillates at its natural frequency. When forcing was applied by periodic light flashes, they found a difference in the kind of response depending on whether the forcing was strong or weak. To quote the authors:

“The entrainment to the forcing can take place even when the oscillator is detuned from an exact resonance [refs]. In this case, a periodic force with a frequency f(f) shifts the oscillator from its natural frequency, f(0), to a new frequency, f(r), such that f(f) / f(r) is a rational number m:n. When the forcing amplitude is too weak this frequency adjustment or locking does not occur; the ratio f(f) / f(r) is irrational and the oscillations are quasi-periodic. In dissipative systems frequency locking is the major signature of resonant response.”

So with strong forcing, “frequency locking” occurs and there is a clear relationship between the frequencies of the periodic forcing and of the BZ systems responsive forced oscillation. However when the forcing is weak, the reaction’s responsive frequency shows a much more complex relation to the forcing frequency, and its resultant oscillations can be described as “quasi-periodic”.

Returning to the ENSO, how could the equatorial Pacific nonlinear oscillator be periodically forced? Periodic forcing of the oceans and of climate in general is a frequent topic of posts at WUWT. There are many such known and potential sources of periodic forcing over a wide range of time-scales. The Milankovich orbital related cycles operate over periods of 105 years to decades and centuries (in the case of resonant harmonics of orbital oscillations). Then there is oscillation in solar output from the 11 year sunspot cycles to the longer periodicities such as the Gleissburg cycles. One persuasive source of PDO forcing is solar-barycentric, as outlined by Sidorenko et al. (2010), the movement of the solar system barycenter around the sub-Jupiter point (center of gravity of a solar system containing only the sun and Jupiter):

This periodic asymmetry in the solar orbit has shown a wavelength and inflection points similar to the PDO cycle in the last two centuries.

Turning to the oceans and the thermo-haline circulation of deep ocean currents, it is well known that the strength of cold water downwelling at the key sites such as the Norwegian sea is subject to significant variation – indeed after a period of a few decades of relative weakness, Norwegian sea downwelling has recently strengthened (Nature, 29 November 2008, doi:10.1038/news.2008.1262 – link in references). Once could go on. There is no shortage of potential sources of periodic forcing of the atmosphere-ocean system, either of the equatorial Pacific or indeed globally.

If the PDO represents the operation of the ENSO Lorenz attractor, then the periodicity of the PDO should tell us if the system is unforced or forced and frequency locked – in which cases it would have regular periodicity, or if it is weakly periodically forced, in which case an irregular wavelength might be expected. Jacoby et al. 2004 traced the PDO oscillations over the last 400 years, using oak tree rings on the Russian Kurille Islands:

http://www.wsl.ch/info/mitarbeitende//frank/publications_EN/Jacoby_etal_PPP_2004.pdf

A PDO wavetrain is clearly discernible but the wavelength varies from 30-60 years. The PDO thus appears to be a real multidecadal oscillation but it is not frequency locked, showing frequency variation. This points to the PDO arising from a weakly periodically forced ENSO. Mantua et al. (2002) also review data on palaeo-records of the PDO, concluding that its wavelength varies from 50-70 years. They concluded that the causes of the PDO are unknown.

http://www.atmos.washington.edu/~mantua/REPORTS/PDO/JO%20Pacific%20Decadal%20Oscillation%20rev.pdf

Thus the PDO seems to be almost but not quite regular – apparently aiming for a 60 year cycle but fluctuating from it. This could be evidence of periodic forcing of the ENSO system that close to the boundary between “weak” and “strong” forcing. Of course, these suggestions about sources of periodic forcing of the ENSO and PDO are speculative. If, as set out by Lin et al. (2004), in the case of a weak periodic forcing of a nonlinear oscillator such as the BZ reactor, the relation between a putative forcing frequency f(f) and the responsive frequency f(r) is irrational, this complicates the search for conclusive proof of such a link. However the PDO’s apparently limited departure from 60 year periodicity might suggest a forcing near the boundary of strong and weak, and therefore an intermittent frequency locking.

Conclusions

- Owing to the far-from-equilibrium state of the earth’s atmosphere and ocean climate system, the a priori case for the operation of non-equilibrium/nonlinear pattern dynamics is strong.

- The Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction-diffusion system in a thin film is a compelling model of a nonlinear oscillation arising spontaneously in a far-from-equilibrium spatially-extended system, with apparent similarities to the ENSO sea surface temperature spatio-temporal oscillation in the equatorial Pacific.

- The apparent positive feedbacks (spatio-temporally limited) associated with the initiation of both el Nino and La Nina systems, linking Peruvian coast deep upwelling with equatorial trade winds, qualify the equatorial Pacific as an excitable medium, a key pre-requisite of an oscillating reaction-diffusion system such as the BZ reaction. The open and dissipative nature of the climate and ocean meet another such requirement.

- Of the class of known attractors of nonlinear oscillatory systems, the Lorenz and possibly Roessler attractors bear similarities to the attractor likely responsible for the alternating phases of La Nina and el Nino dominance that characterise the ENSO and constitute the PDO.

- It is possible that the ENSO / PDO system might be periodically forced; the significant but limited variation of the time-period of the PDO evidenced in the palaeo-record of the last few centuries suggests a forcing strength close to the threshold required for frequency locking.

- If the ENSO and PDO can be characterised as a nonlinear oscillator with a Lorenz type attractor, one might speculatively extend the analogy more widely to the earth’s climate as a whole, and such features as the alternation between glacial and interglacial states (during a glacial epoch such as the present one).

- It is hoped that scientists and mathematicians with expertise in non-equilibrium pattern systems, such as reaction-diffusion oscillatory systems, might bring their analytical techniques to bear on the study of the earth’s atmosphere, oceans and climate. In this way the hypotheses presented here could be confirmed or refuted, and perhaps the nature and identity of the significant drivers of climate could be found.

Postscript

What implications does this paper have for anthropogenic global warming (AGW), if any? It was not written primarily to address the AGW issue. CO2 is not mentioned. However there are some indirect implications. The finding that Bob Tisdale’s observation of alternating periods of el Nino and La Nina dominance – in other words the PDO – is well described by a nonlinear oscillator driven by a torn Lorenz (or Lorenz-Roessler) attractor, give Bob’s conclusions greater “real-world” plausibility. (Nonlinear attractors are a common feature of the real world.) It is also a riposte to those who argue against the reality of the PDO or AMO (Pacific decadal oscillation, Atlantic multidecadal oscillation) on the grounds that a credible mechanism does not exist. It does!

One important mathematical aspect of a nonlinear oscillator with an attractor is its “Lyapunov stability”. Alexander Lyapunov, from Yaroslavl, Russia, established a century ago the maths of stability of both linear and nonlinear systems, such that a nonlinear system such as an oscillator is characterised by a “Lyapunov exponent”. The full works on this are given here:

http://cobweb.ecn.purdue.edu/~zak/ECE_675/Lyapunov_tutorial.pdf

The maths here is all way over my head – I’m a “mere” biologist! Essentially the Lyapunov exponent assesses how strong or “attractive” the attractor is – i.e. how strong a perturbation of the system is needed to move it – unwillingly – away from its attractor. More expert mathematic analysis of the ENSO as nonlinear oscillator would include derivation of the Lyapunov exponents. This would tell us the stability of the system and its resistance to change due to any outside influences.

The global circulation models (GCMs) are essentially linear. That presumably is why they generally fail to reproduce the ENSO and PDO. (If they show any nonlinear behaviour it is probably more by accident than design.) It remains to be seen whether climate and ocean modelling – of the ENSO or of larger parts of the global climate, which used a nonlinear oscillator as a starting point, would be more effective.

Post-postscript

Mathematical / computer modelling of a nonlinear oscillator such as the BZ reaction is not too difficult (for people into that kind of thing) and well established. The “Brusselator” – so named for being invented at the Free University of Brussels (VUB) is a good example:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brusselator

References

Controlling turbulence and pattern formation in chemical reactions. Matthias Bertram, PhD thesis, Berlin, 2002. https://docs.google.com/leaf?id=0B9p_cojT-pflY2Y2MmZmMWQtOWQ0Mi00MzJkLTkyYmQtMWQ5Y2ExOTQ3ZDdm&hl=en_GB

G. Nicolis and I. Prigogine, Self-organization in Nonequilibrium Systems (Wiley, New York, 1977).

E. Schroedinger, What is Life ? (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1944).

P. Glandsdorff and I. Prigogine, Thermodynamic Theory of Structure, Stability and Fluctuations (Wiley, New York, 1971).

The ENSO-Related Variations In Kuroshio-Oyashio Extension (KOE) SST Anomalies And Their Impact On Northern Hemisphere Temperatures. Bo Tisdale, from the web page: http://bobtisdale.blogspot.com/2010/12/enso-related-variations-in-kuroshio.html

Integrating ENSO: Mutidecadal variation in sea surface temperature. Bob Tisdale.

Pdf of this article: https://docs.google.com/leaf?id=0B9p_cojT-pflYjYyMTdkYzItMDMwOS00MjFjLWJmYTAtMzdjYjM1YjhhMmFj&hl=en_GB

Resonance tongues and patterns in periodically forced reaction-diffusion systems. Anna Lin et al., DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevE.69.066217, Cite as: arXiv:nlin/0401031v1 [nlin.PS].

Nature, 29 November 2008, doi:10.1038/news.2008.1262.

http://www.nature.com/news/2008/081129/full/news.2008.1262.html

G. Jacoby, O. Solomina,1, D. Frank, N. Eremenko, R. D’Arrigo (2004) Kunashir (Kuriles) Oak 400-year reconstruction of temperature and relation to the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 209 (2004) 303–311.

http://www.wsl.ch/info/mitarbeitende//frank/publications_EN/Jacoby_etal_PPP_2004.pdf

Mantua et al. (2002)

http://www.atmos.washington.edu/~mantua/REPORTS/PDO/JO%20Pacific%20Decadal%20Oscillation%20rev.pdf

N. Sidorenkov I.R.G. Wilson A.I. Kchlystov (2010) Synchronizations of the geophysical processes and asymmetries in the solar motion about the Solar System’s barycentre. EPSC Abstracts Vol. 5, EPSC2010-21, 2010 European Planetary Science Congress 2010.

![etb58j[1]](http://wattsupwiththat.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/etb58j1.gif?resize=430%2C317)

Paul Vaughan says:

January 27, 2011 at 10:25 pm

To avoid aliasing, I deal mostly with data decimated to yearly, rather than monthly, averages. Thus I have little to say about interannual variability, which is at Nyquist. The subdecadal variations are quite region-specfic; they do not cohere well beyond several hundred kilometers.

phlogiston says:

January 28, 2011 at 3:01 am

Your philosophical ruminations about “arrogant reductionism” are neither here nor there. The great leaps forward in biology in the last several decades were made by physicists such as Bronowski and many others at Salk Institute, looking at biological processes at the molecular level. As mentioned earlier, however, that is not the scale at which geophycisists work. Our goal likewise is to understand the workings of the integral system. I, in particular, who is perpetually testing theoretical expectations against measuremets would be the last one to ignore the implications of field data. But the standard of proof is far more rigorous than just the qualitative similarity of certain features of synthesized index time series. Quantifications of the theoretical expectations need to be tested against the measurements.

I don’t think Bob Tisdale would claim to have discovered any true DYNAMICAL relationship between ENSO and PDO. He provides a phenomenological explanation of a connection, but not one that allows any determination of the energy levels and strength of coupling in the distinct oscillations. And when the similarity of time-series depends on the arbitrary offset in the NINO3.4 index, the scientific credibility suffers.

The whole topic of nonlinear oscillators is fascinating, but best left for another venue. Have a good weekend.

phlogiston;

The existence of “emergent properties” is pretty hard to deny. Observe the long struggle to link the atomic structure of H2O to its many unique characteristics. Complexity has its own logic.

Reductionism’s demand on itself would have to be that all chemistry and structure etc. should be predictable from the properties of subatomic particles — strings, maybe? Good luck with that.

Reductionism vs. holism is a false dichotomy. The term “hierarchy theory” is misleading for those who do not differentiate between grain & extent. For example, a beetle’s ecosystem is not a human’s ecosystem, even if the beetle is perched on the human. Such misunderstandings are inevitable not only in cross-disciplinary communication, but also within disciplines.

I would be curious to hear sometime (in the weeks & months ahead) how sky, who is very careful about temporal aliasing, avoids (or more likely attempts to avoid) issues with spatial aliasing in spatiotemporally nonstationary contexts.

Organization (and along with it Simpson’s Paradox) is just a form of nonrandom aliasing, so it is people like sky who can rigorously carry the ball to the end zone following insightful data exploration (which should absolutely not be confused with statistical inference). [Note that sky is not deriding data exploration – quite the contrary.]

–

Phil, like Erl Happ you are a talented writer, but I have one request:

If you write more articles, please consider (for your busy audience’s sake) keeping them much more succinct. Thank you for considering this request.

Best Regards.

Yes, I had found the Wiki article about limit cycles, from looking up Hopf bifurcations. All the math is over my head, but I believe I got the implications of the limit cycles. Even the Hopf bifurcations seemed to tie in with the upwelling water in the eastern Pacific.

Hopf bifurcation was described as

If one looks at the thermocline perhaps as the “fixed point” and the complex plane being the sea surface, then what might be happening is that the thermocline may be breaking (moving across) the sea surface, and since the thermocline is such a distinct entity/discontinuity, when it drops below the surface the eastern Pacific immediately shifts modes. All because of the interplay of upwelling and other forces/currents/winds pushing and pulling at each other. In this case, the cause of the El Niño has itself a cause, which is of course, linked back to the Hadley cells and the ICZ.

The balancing act is an oscillation, not a single fixed state. The real question must be why climatologists wouldn’t already be aware that this is a normal occurrence in a dynamic system such as the climate, normal enough that it should have been one of the first things they looked for.

…With the one PDO phase change that originally was called the Great Climate Change of 1976-1977, it should have been seen in the 1980s and 1990s that a BZR oscillation was going on. Or suspected it, anyway. The ENSO is even more clear. Seriously, if I’d known the BZR thing existed, I would have been yelling it out long ago. That doesn’t mean it is the definitive answer, but it was sure a hypothesis that should have been thrown into the mix to be falsified or not. And with the ENSO climate effect and then the PDO one, too, it seems to be the best explanation – at least from a semi-lay POV.

I have 3 questions for Feet2theFire:

1) Have you reviewed the literature (which goes back decades) on modeling ENSO as a nonlinear oscillator? (recent example: Warren White at Scripps)

2) Do you believe that mathematical “proofs” that terrestrial climate is chaotic are based on tenable assumptions?

3) Do you believe that strange nonchaotic attractors play no role in terrestrial climate?

Feet2theFire says:

January 29, 2011 at 8:08 am

If one looks at the thermocline perhaps as the “fixed point” and the complex plane being the sea surface, then what might be happening is that the thermocline may be breaking (moving across) the sea surface, and since the thermocline is such a distinct entity/discontinuity, when it drops below the surface the eastern Pacific immediately shifts modes. All because of the interplay of upwelling and other forces/currents/winds pushing and pulling at each other. In this case, the cause of the El Niño has itself a cause, which is of course, linked back to the Hadley cells and the ICZ.

This looks like it could be a starting point for going from a hand-waving analogy of BZR-ENSO and discussion of pre-requisite conditions, to a testable model. I mentioned that the BZR is readily simulated by computer, the “Brusselator” is a well known example. One aspect of the upwelling that I focused on is that is certain places and times it might become self-accelerating, e.g. upwelling cold water might influence trade winds in such a way as to drive further upwelling, connecting a positive feedback. The inverse in the case of el Nino – weakened upwelling would self-limit further by the same trade winds link. This would qualify the upwelling region as an excitable medium, a pre-condition for a BZ style nonlinear oscillator.

It should be possible to obtain more data on the behaviour of the thermocline in that region and other Bob Tisdale type meteorological data on the ENSO to have the basis of a testable model.

The balancing act is an oscillation, not a single fixed state. The real question must be why climatologists wouldn’t already be aware that this is a normal occurrence in a dynamic system such as the climate, normal enough that it should have been one of the first things they looked for.

…With the one PDO phase change that originally was called the Great Climate Change of 1976-1977, it should have been seen in the 1980s and 1990s that a BZR oscillation was going on. Or suspected it, anyway. The ENSO is even more clear. Seriously, if I’d known the BZR thing existed, I would have been yelling it out long ago. That doesn’t mean it is the definitive answer, but it was sure a hypothesis that should have been thrown into the mix to be falsified or not. And with the ENSO climate effect and then the PDO one, too, it seems to be the best explanation – at least from a semi-lay POV.

There have been a few published papers which mention the BZ reaction and ENSO in the same paper, speculating that ENSO might be a nonlinear oscillator (indeed an obvious enough proposition) and mentioning the BZ reaction as one of the best studied exampes of an experimental nonlinear oscillator in a chemical reaction-diffusion system. I mentioned above in reply to Paul Vaughan a paper by Lockwood back in 2001 where he wrote:

“For example, the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction in inorganic chemistry …

Because the movement from one stable state to another, as the distance from equilibrium increases, depends on universal numerical features rather than the actual mechanisms involved, it is not surprising that some of the curves look similar to climatological time series.”

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/joc.630/pdf

J. Lockwood, “Abrupt and sudden climatic transitions and fluctuations: a review” (

Int. J. Climatol. 21: 1153–1179, 2001).

However the BZ-ENSO link has indeed been very marginal to the ENSO discussion and I am sure you are far from alone among even scientists studying the ENSO professionally, in being previously unaware of the BZ reaction. Much of the mainstream discussion of ENSO ignores the non-linear oscillator paradigm.

This is the point about fences between scientific disciplines and parochialism. Scientists publish in densely technical code specifically to exclude outsiders, to the detriment of science as a whole.

More gate-crashing is needed!

@Paul Vaughn –

Answers for you:

1) Have you reviewed the literature (which goes back decades) on modeling ENSO as a nonlinear oscillator? (recent example: Warren White at Scripps)

Ans: No. Although I’ve read a whole lot. Maths are generally over my head. This article is the first I’ve run across that addresses nonlinear oscillators at all. Literally, I’ve been looking for years for some cause of El Niño. Online searches have been useless – hit after hit of what ENSO affects, and nothing on the other side of the equation.

2) Do you believe that mathematical “proofs” that terrestrial climate is chaotic are based on tenable assumptions?

Ans: Two responses. First, I think if there were mathematical proofs – in quotes or not – the models would do a better job, so no on that account. Second, chaos is something I know little about and haven’t the time or background to get into. I am not even sure chaos is quite applicable. Just because something is too complicated for our present ability to study doesn’t mean it has to be chaotic. Third, what their assumptions are, I have no clue.

3) Do you believe that strange nonchaotic attractors play no role in terrestrial climate?

Ans: The maths are over my head, but the implications of what I am reading only just now are fascinating me. As much as I can glean from them. I only just heard of attractors of any kind, much less be able to distinguish one from another.

Thanks for the questions, but they are over my head, to be honest with you. That doesn’t mean I can’t grasp some of the principles behind what is happening. Since the level of connecting all of the maths to climate seem not to have gotten anyone complete understanding of climate, I assume some of their underlying concepts are, indeed, untenable. Which ones? I think that is why I am trying to grasp this all in the first place. I have a fairly adept spatial visualization capacity, and I can envision some of what is going on. I guess I am similar to the generalist ancient Greeks who tried to explain everything conceptually. If someone throws math at me, I will ask what principles are behind it and what they believe it implies. That is my level. Again thanks for asking.

Feet2theFire, Thanks for your response. A simple example of a strange nonchaotic attractor: Tides. Russian scientists have suggested something a little more complicated for terrestrial climate, but that story is for another day…

Cheers.

@phlogistin –

I have an impression it would more directly affect the ICZ’s convection, rather than the tradewinds. I see the trade winds begging the inflow before the air reaches the equator, therefore being on the last leg of the Hadley cell loop of air. The first thing affected would seem to be the ICZ. Basically there are two upwellings – one in the ocean and one in the troposphere. Or not. No?

Basically, the thermocline dropping below the surface would be a brake on the ICZ, by cutting off one of its two inflows of heat energy.

In a dynamic system, I just don’t see equilibrium being a single energy state. It is much more likely to be either some randomness within two boundaries or some sort of oscillation.

From a geographical perspective:

In the equatorial Pacific off Peru/Ecuador, the convection that uplifts the cold water – convection is a low-intensity force. (This is one reason why I argue elsewhere against its being a driving force in the THC.) It would seem this is relatively easily overcome by incoming trade-wind-pushed warmer surface waters from the surrounding region just to the north, over the top of the cold plume, effectively capping it. There is normal a great deal of heat energy off the Central American/Mexican coast, which happens to be the birthing place of many of the Pacific hurricanes. (Having spent time in SW Mexico, I pay attention to their weather systems.) There are seemingly always plumes of heated atmosphere there (though, ironically, not at the moment). It doesn’t seem that very much of it would need to move south to cap off the cold plume.

(One question might be why this happens in the Pacific and not in the Atlantic off the west cost of Guinea. My first intuition on this is that the shape of the African coast blocks the southern flow just north of the Equator, pushing the equator-ward water to the west and disrupting what in the Pacific is a more clean, unhindered system. In looking at the currents, the Equatorial Counter Current and the Benguela Current more or less run head-on into each other near the SW corner of the bulge of Africa. The coast there has to be contributing mightily to the inability of the cold Benguela Current having a bigger effect. Off South America, the Equatorial Counter Current has a free flow path to the coast instead of being pinched off as the Atlantic one is. The pinching off makes the Atlantic one that is more chaotic. It would also seem to stretch the cold plume out to the west and diffuse it over that whole distance, moderating its extreme.)

In my mind oscillating is an organized mechanism. I would think that, in effect, makes it the opposite of chaos. Lack of geographic complications in the Pacific would seem to suggest why we have a Pacific ENSO and not an Atlantic one. (I don’t see the AMO as the same thing.) Organization and oscillation are cleaner in the Pacific – once a regime begins to take hold, it has less to disrupt its growing until it reaches its own feedback from overshooting. This, I suppose is when the cold plume’s convection cannot be held down anymore by the intrusive warm cap from the north.

I am probably looking at all this too simplistically, but it is just incredible to me that people havn’t see this mechanism as the probable cause of El Niño.

@Paul Vaughn –

“Russian scientists have suggested something a little more complicated for terrestrial climate…”

Any links you’d want to point me to?