That is a total of 365,000 high temperature records and 365,000 low temperature records. During the second year of operation, each day and each station has a 50/50 chance of breaking a high and/or low record on that date – so we would expect about 182,500 high temperature records and about 182,500 low temperature records during the year.

In the third year of the record, the odds drop to 1/3 and the number of expected records would be about 121,667 high and low temperature records.

In a normal Gaussian distribution of 100 numbers (representing years in this case,) the odds of any given number being the highest are 1 out of 100, and the odds of that number being the lowest are also 1 out of 100. So by the 100th year of operation, the odds of breaking a record at any given station on any given day drop to 1/100. This mean we would expect approximately 1000 stations X 365 days / 100 years = 3,650 high and 3,650 low temperature records to be set during the year – or about ten record highs per day and ten record lows per day.

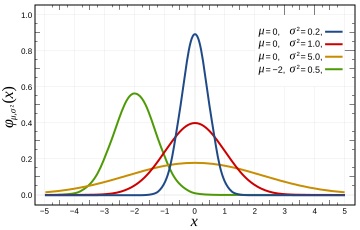

This provides the news media lots opportunity to get hysterical about global warming every single day – even in a completely stable temperature regime. The distribution of temperatures is Gaussian, so it won’t be exactly ten per day, but will average out to ten per day over the course of the year. In a warming climate, we would expect to see more than 10 record highs per day, and fewer than 10 record lows per day.

In a cooling climate, we would expect to see more than 10 record lows per day, and fewer than 10 record highs per day. The USHCN record consists of more than 1000 stations, so we should expect to see more than 10 record highs per day. Throw in the UHI effects that Anthony and team have documented, and we would expect to see many more than that. So no, record high temperatures are not unusual and should be expected to occur somewhere nearly every day of the year. They don’t prove global warming – rather they prove that the temperature record is inadequate.

No continents have set a record high temperature since 1974. This is not even remotely consistent with claims that current temperatures are unusually high. Quite the contrary.

| Continent | Temperature | Year |

| Africa | 136F | 1922 |

| North America | 134F | 1913 |

| Asia | 129F | 1942 |

| Australia | 128F | 1889 |

| Europe | 122F | 1881 |

| South America | 120F | 1905 |

| Antarctica | 59F | 1974 |

http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0001375.html

Here is the code discussed in comments:

// C++ Program for calculating high temperature record probabilities in a 100 year temperature record

// Compilation : g++ -o gaussian gaussian.cc

// Usage : ./gaussian 100

#include <iostream>

main(int argc, char** argv)

{

int iterations = 10000;

int winners = 0;

int years = atoi(argv[1]);

for (int j = 0; j < iterations; j++)

{

int maximum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < years; i++)

{

maximum = std::max( rand(), maximum );

}

int value = rand();

if (value > maximum)

{

winners++;

}

}

float probability = float(winners) / float(iterations);

std::cout << "Average probability = " << probability << std::endl;

}

Discover more from Watts Up With That?

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Steven Goddard

The mechanism by which you infer the odds year-on-year of a temperature being a record high or low is fundamentally flawed.

The post by “Phil.” at 21:42:12 on 28 Apr 09 explains the reasons why.

You need to re-calculate the expected number of broken records taking Phil’s comments into account.

This number will be lower than your initial calculations, which suggests to me that record highs and lows have more significance as climate “events”.

I still think the hypothesis that more high records should be broken than low records in a warming climate is valid. The question is, what is the likelihood of such an occurrence in your scenario’s stable climate? Only than can we assess the significance of actual measurements.

I feel you do good work, Steven, but I think this article was insufficiently rigorous.

Steven Goddard:

Your 15:10 post on the 28th shows quasi-gaussian temperature readings at Bergen for a month. My earlier comment about likely non-normality, however, concerned the daily MAXIMA, whose EXTREME values result in RECORDS. Not the same thing at all.

I became aware of this fallacy when I started attending high school. The papers were full of stories about athletes frequently setting new school records. The school was only 5 years old when I was a freshman, so it was relatively easy to set new records- roughly 1 in 5 records could be expected to be broken at that time, 1 in 6 my sophomore year, etc.

hey anthony! thread idea.

wondering if this is sign of bias toward warming reporting in the media … bear with me.

google trends reports US news mentions (second graph) for “record high temperature” stomp over news mentions of “record low temperatures” over the last few years.

http://trends.google.com/trends?q=record+low+temperature%2C+record+high+temperature&ctab=0&geo=us&geor=all&date=all&sort=1

this despite the fact that no state has reported a record high temperature since 1995, according to infoplease/NCDC/StormFax:

http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0001416.html

not really statistically savvy enough to know if a 14-year gap (1995-2009) is a long time to go without a record high in at least one state out of 50 … the previous gaps were 11 years (’83-’94), 8 years (’75-’83) and 14 years (’61-’75). but that’s beside the point.

why would the media report more about record highs than record lows during a period when there were apparently few record highs set?

presumably the record high reporting was not about US states, but rather about other countries or perhaps individual towns within the US, which could obviously have their own record highs without affecting the respective state’s record high. so a little more research is in order here. would be interesting to see whether there were more record highs than record lows in US towns and cities over the last few years (the period google trends tracks).