From Dr. Roy Spencer’s Global Warming Blog

by Roy W. Spencer, Ph. D.

The Version 6 global average lower tropospheric temperature (LT) anomaly for August, 2024 was +0.88 deg. C departure from the 1991-2020 mean, up slightly from the July, 2024 anomaly of +0.85 deg. C.

Persistent global-averaged warmth was (unusually) contributed to this month by the Southern Hemisphere. Of the 27 regions we routinely monitor, 5 of them set record-warm (or near-record) high monthly temperature anomalies in August, all due to contributions from the Southern Hemisphere:

Global land: +1.35 deg. C

Southern Hemisphere land: +1.87 deg. C

Southern Hemisphere extratropical land: +2.23 deg. C

Antarctica: +3.31 deg. C (2nd place, previous record was +3.37 deg. C, Aug. 1996)

Australia: +1.80 deg. C.

The linear warming trend since January, 1979 now stands at +0.16 C/decade (+0.14 C/decade over the global-averaged oceans, and +0.21 C/decade over global-averaged land).

The following table lists various regional LT departures from the 30-year (1991-2020) average for the last 20 months (record highs are in red):

| YEAR | MO | GLOBE | NHEM. | SHEM. | TROPIC | USA48 | ARCTIC | AUST |

| 2023 | Jan | -0.04 | +0.05 | -0.13 | -0.38 | +0.12 | -0.12 | -0.50 |

| 2023 | Feb | +0.09 | +0.17 | +0.00 | -0.10 | +0.68 | -0.24 | -0.11 |

| 2023 | Mar | +0.20 | +0.24 | +0.17 | -0.13 | -1.43 | +0.17 | +0.40 |

| 2023 | Apr | +0.18 | +0.11 | +0.26 | -0.03 | -0.37 | +0.53 | +0.21 |

| 2023 | May | +0.37 | +0.30 | +0.44 | +0.40 | +0.57 | +0.66 | -0.09 |

| 2023 | June | +0.38 | +0.47 | +0.29 | +0.55 | -0.35 | +0.45 | +0.07 |

| 2023 | July | +0.64 | +0.73 | +0.56 | +0.88 | +0.53 | +0.91 | +1.44 |

| 2023 | Aug | +0.70 | +0.88 | +0.51 | +0.86 | +0.94 | +1.54 | +1.25 |

| 2023 | Sep | +0.90 | +0.94 | +0.86 | +0.93 | +0.40 | +1.13 | +1.17 |

| 2023 | Oct | +0.93 | +1.02 | +0.83 | +1.00 | +0.99 | +0.92 | +0.63 |

| 2023 | Nov | +0.91 | +1.01 | +0.82 | +1.03 | +0.65 | +1.16 | +0.42 |

| 2023 | Dec | +0.83 | +0.93 | +0.73 | +1.08 | +1.26 | +0.26 | +0.85 |

| 2024 | Jan | +0.86 | +1.06 | +0.66 | +1.27 | -0.05 | +0.40 | +1.18 |

| 2024 | Feb | +0.93 | +1.03 | +0.83 | +1.24 | +1.36 | +0.88 | +1.07 |

| 2024 | Mar | +0.95 | +1.02 | +0.88 | +1.35 | +0.23 | +1.10 | +1.29 |

| 2024 | Apr | +1.05 | +1.25 | +0.85 | +1.26 | +1.02 | +0.98 | +0.48 |

| 2024 | May | +0.90 | +0.98 | +0.83 | +1.31 | +0.38 | +0.38 | +0.45 |

| 2024 | June | +0.80 | +0.96 | +0.64 | +0.93 | +1.65 | +0.79 | +0.87 |

| 2024 | July | +0.85 | +1.02 | +0.68 | +1.06 | +0.77 | +0.67 | +0.01 |

| 2024 | August | +0.88 | +0.96 | +0.81 | +0.88 | +0.69 | +0.94 | +1.80 |

The full UAH Global Temperature Report, along with the LT global gridpoint anomaly image for August, 2024, and a more detailed analysis by John Christy, should be available within the next several days here.

Lower Troposphere:

http://vortex.nsstc.uah.edu/data/msu/v6.0/tlt/uahncdc_lt_6.0.txt

Mid-Troposphere:

http://vortex.nsstc.uah.edu/data/msu/v6.0/tmt/uahncdc_mt_6.0.txt

Tropopause:

http://vortex.nsstc.uah.edu/data/msu/v6.0/ttp/uahncdc_tp_6.0.txt

Lower Stratosphere:

http://vortex.nsstc.uah.edu/data/msu/v6.0/tls/uahncdc_ls_6.0.txt

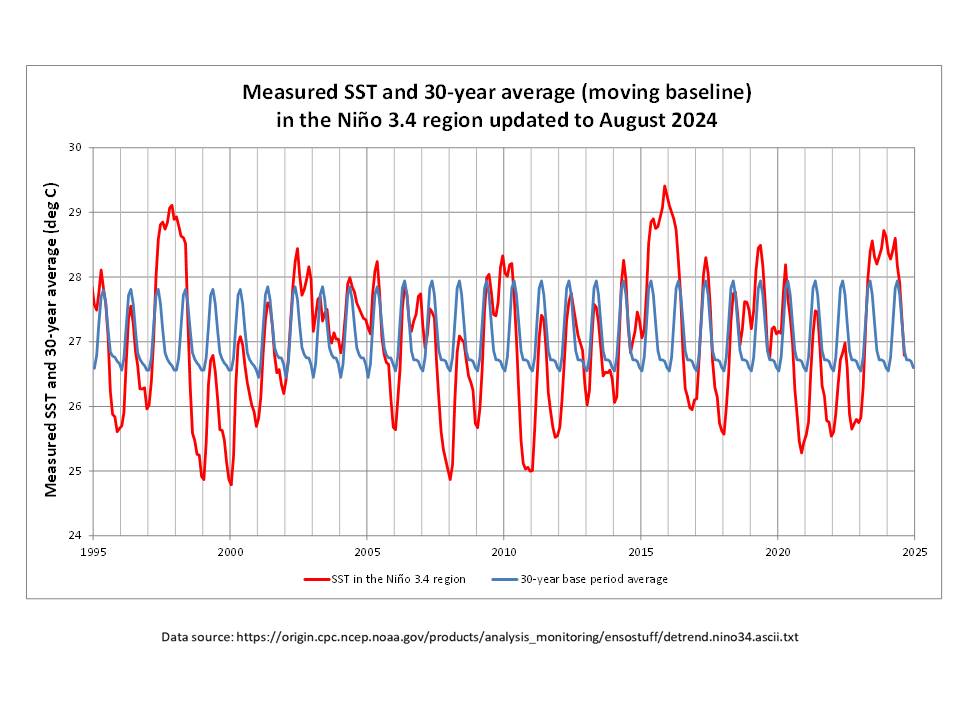

Is this Southern contribution related to ENSO?

If it is then it is a very unusual ENSO compared to previous events in the record.

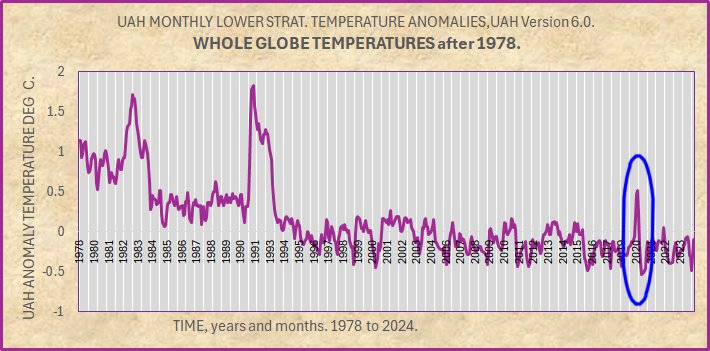

This entire post-El Nino peak is atypical. If the Hunga Tonga eruption isn’t responsible for this anomalous peak, then the experts need to be looking for another explanation.

El Niño and La Niña are two opposing climate patterns that break these normal conditions. Scientists call these phenomena the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle. El Niño and La Niña can both have global impacts

Thanks for once again showing us that you can’t comprehend a simple question.

The global impact of major El Ninos is totally obvious.. a spike and a step change.

So… Show us the global impact of La Ninas in the UAH data.

Or FAIL again.

So you FAILED again.. as expected.

The WUWT ENSO meter, found on the lower part of the right-hand column of this webpage below the listing of Bookmarks is currently reading 0.0 . . . smack in the middle of the “neutral” zone.

Hint to WUWT editors: it may be time to add another meter adjacent to the current one . . . call it the ENSO “delay time” meter, with a scale ranging from 0 to 24 months.

/sarc

I don’t get the /sarc tag?

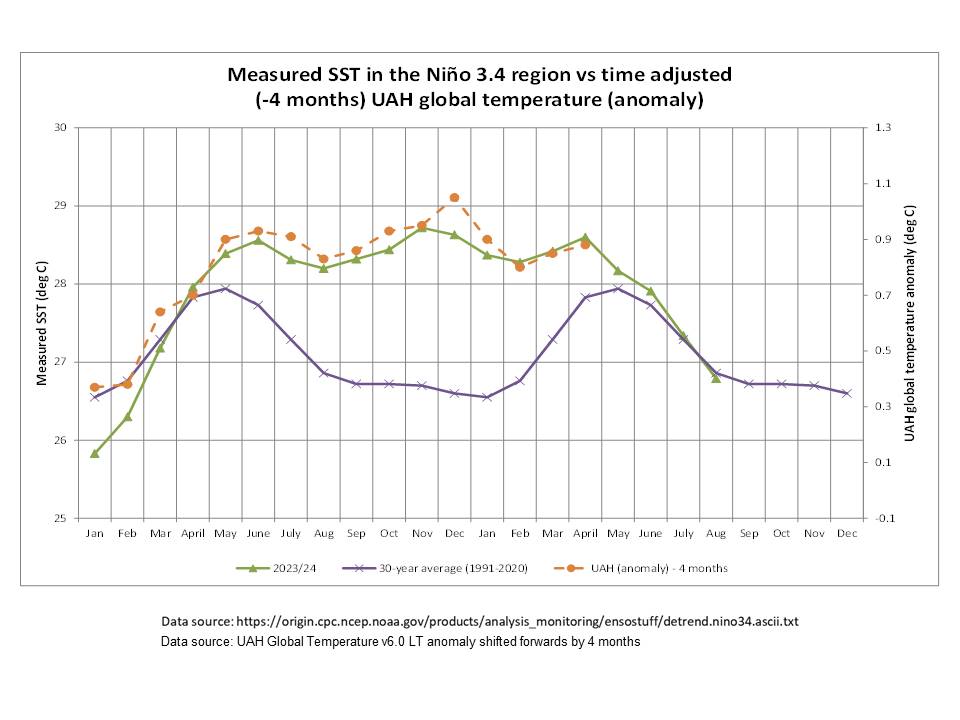

Elevated UAH temperatures always persist for some lag period after the end of an El Nino event.

Please define “some lag period”, assuming it’s not two years or longer.

Hint: the /sarc tag is to reflect that there are no deterministic time lags or occurrence frequencies associated with ENSO events.

Enso meter is based on a small section of ocean in the middle f the ENSO region.

It does not show how wide-spread the El Nino effect is.

Are you sure about that?

WUWT editor Ric Werme maintains the WUWT ENSO meter and states that he obtains the relevant sea-surface temperature measurements from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) . . . reference https://wattsupwiththat.com/2024/08/30/friday-funny-troll-or-serious/#comment-3962120

In turn, here is what the BoM itself has to say about calculating the ENSO:

“The Southern Oscillation Index, or SOI, gives an indication of the development and intensity of El Niño or La Niña in the Pacific Ocean. The SOI is calculated using the pressure differences between Tahiti and Darwin.”

(http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/about/?bookmark=enso )

FYI, the span distance between Tahiti and Darwin is 8,515 km . . . something few knowledgeable persons would classify as “small”.

No, probably not, just not letting it dissipate as it usually does.

Looks like some sort of stratosphere event causing the warming weather around Australia and the SH.

Record 50C temperature increase over Antarctica to shift Australia’s weather patterns – ABC News

The red text headline is, at best, an alarming half-truth for the associated hyperlinked ABC News article.

If you read the details in that article, you find the 50 °C increase is associated with a localized hot spot in the stratosphere off the east coast of Antarctica. It is not over the continent of Antarctica.

Furthermore, the article states the following:

“Technically the warming of the stratosphere is required to average at least 25C to be classified as a true SSW {sudden stratospheric warming}, and while this event’s warming has doubled that figure near the east Antarctic coast, the average warming over the whole of Antarctica may have so far peaked just below the threshold.”

with the graphic that I’ve posted here taken directly from under that statement in the article.

Two things to note:

1) the warming event took place at the 10 hPa level in the stratosphere and near the worst of the Antarctic winter,

2) the average warming over Antarctica at 10 hPa altitude at that time was only about one-third the average warming that occurs naturally between winter and summer over Antarctica.

Hmmmm . . . the “news” doesn’t appear to be really all that alarming when you look into the matter, as opposed to just reading the headline.

Unusual for this time of year, and what caused the latter half of August to be decidedly warmer than usual.

…

Guess what, the last couple of weeks of August were sort of unusually warm for this time of year.

Oh dear . . . there it is again, a dire warning of the POSSIBILITY of totally-undefined “extreme weather”.

Me? . . . I give that phrase all the importance that it deserves.

Definitely not, it is the water vapor from the HT eruption.

And it does not appear to be going away anytime soon in the Southern Hemisphere, the Northern Hemisphere is still under the effects but there are other factors at play.

Graphics produced by IDL (nasa.gov)

“it is the water vapor from the HT eruption.”

requires repeating. !!

The unusual warming over the last two years globally, seems like a slam dunk for HT. But I think there are a number of researchers out there that love WaveTran / ModTran more than they like anecdotal evidence.

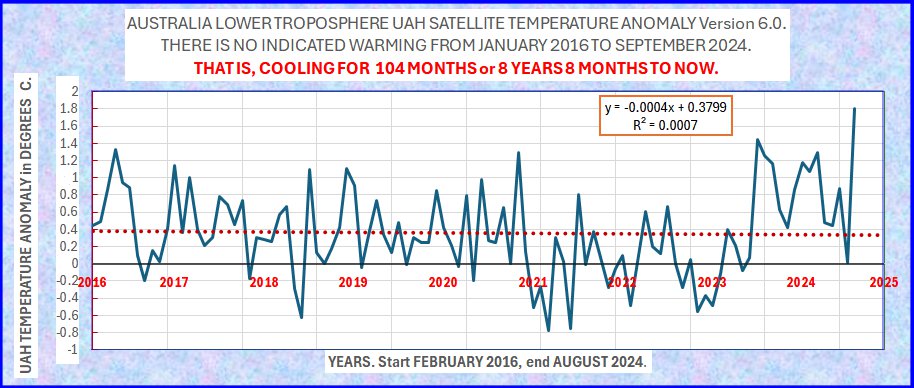

The reason that Australia did not see records last year was because of the Brushfire particulates in the Stratosphere, in which the biggest fires were from 2019 – March of 2020. You can see on the middle plot of Australia UAH LT that temps were down considerably from 2021 until mid 2023. The particulates are gone now, and Australia is getting more sunlight. These are July values; it will be mid-month before August data is downloadable. The Stratosphere over Australia has been quite busy since 2016.

The top graph in your attachment defines the “lower stratosphere” over Australia to be at altitudes of 14–20 km.

I believe what you are discussing is more properly describing perturbations (including expansion in overall thickness/height) of the tropopause and not the stratosphere, which is never properly defined by reference to absolute altitude.

The Tropopause is available in the UAH catalog, the Lower Stratosphere and the Tropopause are disseminated by the UAH processing techniques.

The altitude range of all layers of the atmosphere vary with latitude, with the equator being the thickest portion and the poles being the thinnest. Those altitude ranges annotated in the title of the plot are global ranges, and not specific to Australia.

I did not provide the titles for each of the three graphs in the image that you provided above.

Assuming that you yourself did not create and title those graphs, I strongly suggest that you inform the source of those graphs (which I seriously doubt to be UAH) of your stated observations/corrections.

It is not my problem that you do not know what you are talking about. From prior experience with your comments and with your blatant lack of knowledge on the subject of atmospheric physics, I will thereby allow you to vent your chaos.

There can be no more contact, fire away.

Thank you for your permission.

“And it does not appear to be going away anytime soon in the Southern Hemisphere . . .”

It may, even, last forever!

Don’t be stupid. you make yourself look like fungal or RG

It is just dissipating rather slowly, as was initially predicted.

So, given your statements, what have you or others determined to be the exponential (or is it linear?) decay constant associated with the “dissipation”?

Remember, “don’t be stupid”.

So, you are determined to be stupid..

except maybe you don’t have a choice !

I think the upper troposphere changes are more important at the moment. This shows the water vapor is now reaching that altitude.

The Tropopause will be influenced by the radiative properties of the mid and upper stratosphere. Essentially it is feedback, because all IR leaving the planet must go through the Stratosphere, including the IR emanating from the cloud tops. One of the big problems here is there is very little known about the coupling of the radiative properties of the Stratosphere in conjunction with the Tropopause / Troposphere.

Research of these things are in their infancy at this moment in time, but this experiment by nature hopefully will shed light on how Earths energy budget really works. The claim made by many including the UAH team that significantly increasing water vapor in the Stratosphere will have little effect on the temperature of this planet appears to be based on invalid assumptions / physics.

Correct me of I’m wrong(I’m still learning the intricacies of the Globul Whaaming scam) but showing that HT is responsible for any of the alleged warming would be very inconvenient for the AGW cult. Because it takes away from their main theological point: that humans cause it.

So in no way are they inclined to point to any other possible information.

Climate scientists already accept that volcanoes can cause temperature changes. Afterall, it was climate scientists who discovered this. They even hypothesize that the HT eruption itself is partly the cause of the warming over the last couple of years and expect regional effects to last another 5 years.

HT being a contributing factor to warming is more inconvenient for contrarians because it would show that a mere 150 MtH2O was all it took. To put that into perspective 150 MtH2O represents only a 0.0003 ppm increase in the atmosphere.

Avoiding the main question, as usual.

What is the ppm in the stratosphere and not the whole atmosphere.

No, Australia’s sudden temperature rise is easily explained with a series of links from a very ‘progressive’ media outlet

“Not climate change but ‘natural phenomenon’

In September 2019 Australia’s ABC news reported on sudden stratospheric warming in Antarctica that lead to a spring spell of warming – that lasted months.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-09-06/rare-weather-event-over-antarctica-drives-hot-outlook/11481498

.

In late July 2024 Australia’s ABC news reported that there was another outbreak of SSW – in which they reported that this would likely cause warming over Australia – that could last months

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-07-27/nsw-antarctica-warming-over-50c/104142332

.

On August 26th & 29th Australia’s ABC news reported that “Climate Change” was wholly responsible for the current August warm spell in Australia.”

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-08-26/winter-weather-40-degrees-in-august/104271368

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-08-29/winter-ends-with-heatwave-as-climate-change-upends-seasons/104279250

It is interesting how the temperature anomaly spiked up then plateaued, something not seen in previously in the record.

If you believe the UAH numerical data given in the table in the above article has a meaningful precision to the nearest 0.01 °C, then there hasn’t been any recent plateau in GLAT.

UAH claims an uncertainty of ±0.20 C for the monthly anomalies.

[Christy et al. 2003]

BFD. They don’t understand measurement uncertainty analysis any better than you (don’t).

So, why did you claim there is an acceleration of 0.028C per decade?

First…it is 0.0028 C per decade squared. Anyway that is what Excel’s LINEST function reports.

It is totally MEANINGLESS because it relies on one major El Nino event at the end of the record.

It is just a moronically stupid calculation to even bother doing with the data at hand.

Excel isn’t ‘smart’ enough to pick the correct number of significant figures. That is left up to you. Guess what?

Are you sure about that?

You tell me Clyde. Go ahead…tell me what the correct number of digits is? Don’t forget to show your work because you know I’m chomping at the bit to show you exactly what the standard error of the quadratic polynomial coefficient is and why I choose 2 significant figures. So yeah, let’s go down this rabbit hole shall we.

The last decimal place should match the uncertainty. If the uncertainty is +/- 0.2C (as YOU quote) then their average temperature should be only given to the tenths digit, not the hundredths or thousandths digit.

This legislates against calculating anomaly differences in the hundredths digit!

Just one more rule of physical science that climate science ignores, just like they ignore measurement uncertainty, data variances, and kurtosis/skewness factors for the data sets.

Excellent . . . and just so.

If he were to plot his quadratic fit inside realistic uncertainty limits, those tiny numbers of “acceleration” would look even more silly.

“The last decimal place should match the uncertainty. “

Yes, for the monthly values. Not for the decadal acceleration. The standard error for that acceleration is ~0.00054 deg/decade^2, assuming expected values for every month. If the 2 sigma uncertainly for each monthly value is +/-0.2C, that standard error zooms all the way to ~0.00067 deg/decade^2/ Still the required number of left handed zero’s to show that bd is using the right number of sig figs.

Been laughing and lurking for weeks now, but couldn’t let this one go by…

Once again you are assuming the stated value of a measurement given as “stated value +/- measurement uncertainty” is 100% accurate, thus ignoring the measurement uncertainty part of the measurement.

ANY trend line within the uncertainty interval is equally probable. Meaning you may very likely not be able to determine the actual sign of the slope if the measurement uncertainty is significant.

Your use of the term “standard error” is what gives you away as well That is how precisely you have calculated an average based on assuming the stated values are 100% accurate.

You *still* don’t have a grasp of metrology concepts at all.

“Once again you are assuming the stated value of a measurement given as “stated value +/- measurement uncertainty” is 100% accurate, thus ignoring the measurement uncertainty part of the measurement.”

And once again, you’re introducing those Big Foot unknown uncertainty sources. They might be systemic. They might not. They might be already included in the +/- measurement uncertainty (hint: they probably are), but they might not. They might be large. They might be small. But if they are systemic, they might magically line up over time in such a way as to substantially change averages, trends, trend accelerations. Through it all, your story remains. They’re out there, so any data evaluations based on current info are null and void. That’s your story, and you’re stickin’ with it.

At least you’re not venturing out of your WUWT comfort zone, so there’s that…

A classic blob hand-waved word salad.

You are so full of it that it is coming out of your ears.

All of the recognized metrology experts say that systematic measurement uncertainty is not amenable to being identified using statistical analysis – meaning you simply can’t assume that it all cancels. Assuming such *is* making a statistical assumption that is not justified.

it’s been pointed out to you before that almost all electronic measurement devices today drift in the same direction because of heating of the components due to carrying current. That means all you can assume is that the systematic bias gets larger over time, the only question to answer is how large it gets.

I asked you once to give me a material used in electronic components that shrinks when heated. You failed. I ask you again: give me an electronic component used today that shrinks when heated. I have no doubt you will fail again.

When the measurement uncertainty interval is wider than the difference you are trying to identify then there is no way to know if you have actually identified a true difference or not. That is just a plain, physical reality. It means that you can’t tell if tomorrow is cooler or warmer than today unless the difference is greater than the measurement uncertainty. It means you can’t tell if last August was warmer or cooler than this August unless the difference is greater than the measurement uncertainty. That’s the whole idea behind significant digits – so you don’t claim more resolution in your measurements than the instrument and its measurement uncertainty provides for.

You would have us believe that you and climate science have a cloudy crystal ball that you can use to abrogate that physical reality of measurement uncertainty.

Why are you using standard error as a measure of uncertainty? These are ALL single measures of different things. They fall under reproducibility conditions. This means Standard Deviation of the values is the appropriate measurement uncertainty. The SD informs one of an interval where each measurement has a 68% of falling. In addition a Type B uncertainty should be added for repeatability conditions.

Using standard error as you do, assumes each value of the dependent values are 100% accurate. Show us linear regression software that allows one to input ± measurement uncertainty values along with the stated values and assesses the combined measurement uncertainty.

Here is a paper discussing some of the issues.

https://www2.stat.duke.edu/courses/Fall14/sta101.001/slides/unit7lec3H.pdf

And a stack exchange discussion.

https://stats.stackexchange.com/questions/235693/linear-model-where-the-data-has-uncertainty-using-r

“Show us linear regression software that allows one to input ± measurement uncertainty values along with the stated values and assesses the combined measurement uncertainty.”

From your second link:

“If you know the distribution of the data you can bootstrap it using the boot package in R.”

But you can bootstrap in excel just as effectively, if less automatically. And if the data distributions changed over time, then that could be accommodated with almost no extra work. Here’s how:

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2024/09/02/uah-global-temperature-update-for-august-2024-0-88-deg-c/#comment-3964376

Cherry picking at its finest. That it doesn’t apply to the problem is irrelevant isn’t it?

Did you not read the followup answer that explained in more detail how to handle uncertainty.

Just to elucidate.

https://sites.middlebury.edu/chem103lab/2018/01/05/significant-figures-lab/

https://web.mit.edu/10.001/Web/Course_Notes/Statistics_Notes/Significant_Figures.html#Carrying%20Significant

https://web.ics.purdue.edu/~lewicki/physics218/significant

Uncertainties should usually be rounded to one significant digit. There are some instances when the largest digit is a “1” that two significant digits are appropriate.

These referencies are from highly ranked universities and show how they require measurements to be treated. It really doesn’t matter that the measurement results are from a quadratic polynomial. It is the uncertainty that controls what significant digits should be used.

First off, I defer to Tim Gorman as he beat me to it. I concur.

Secondly, you are presenting a straw man argument. I wasn’t questioning the number of digits you chose to report. I was specifically questioning your blind acceptance of anything reported by Excel instead of demonstrating that what you reported was correct.

You will have to continue chomping at the bit. I hope you don’t chip a tooth while you are at it.

I have doubts that this issue is just a result of bdgwx’s uncritical acceptance, particularly since he was the one who first highlighted the monthly uncertainty from Christy’s publication.

Further to the point and in addition to me correcting the claim of ±0.01 C when it is likely closer to ±0.2 C for the monthly anomalies Spencer and Christy also report the uncertainty of their trend as ±0.05 C.decade-1 while my own assessment using the AR(1) method suggests it was closer to ±0.1 C.decade-1 through 2002…higher than what they reported. So apparently “blind acceptance” is defined so broadly that not accepting they’re published result and doing my own analysis still somehow qualifies.

First…I think deferring to a guy who thinks sums are the same thing averages, that plus (+) is equivalent to division (/), that d(x/n)/dx = 1, that Σa^2 = (Σa)^2, and that sqrt[xy^2] = xy is pretty risky [1][2][3]. But whatever. You do you.

Second…per the rules he posted (which I have no problem with) the correct way to report the coefficient of the quadratic term is 0.028 C.decade-2.

Are you suggesting that Excel’s LINEST function has a bug?

Dipping into the enemies’ files again? You must be desperate.

You are the one that thinks the average uncertainty is the uncertainty of the average.

If q = Σx/n then the uncertainty of q is the uncertainty of Σx plus the uncertainty of n. Since the uncertainty of n is 0 (zero), the uncertainty of q is the uncertainty of Σx.

u(Σx) / n is the AVERAGE UNCERTAINTY, not the uncertainty of the average.

The uncertainty of an average is related to the variance of the data set, not to the average variance of the individual data elements. If the temperature are variables that are iid (which climate science assumes even though it is physically impossible) then the variance of the data set is the sum of the variances of the individual variables, not to the variance of a single individual variable.

Nor is the measurement uncertainty of the average value equal to the sampling uncertainty (the SEM), i.e. how precisely you have located the average value which you have also advocated. The measurement uncertainty *adds* to the sampling uncertainty.

“Second…per the rules he posted (which I have no problem with) the correct way to report the coefficient of the quadratic term is 0.028 C.decade-2.”

This makes no sense. A dimension of “C.decade-2” is meaningless. If you are trying to do addition of uncertainties is quadrature then the result is the square root of the squared value.

“Are you suggesting that Excel’s LINEST function has a bug?”

go here: https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/linest-function-84d7d0d9-6e50-4101-977a-fa7abf772b6d

Look at Example 3. The inputs have at most 4 significant figures. Yet the result of the function comes out with results like “13.26801148″. Far more significant digits than the inputs – meaning the LINEST function does *NOT* use significant digit rules used for physical science.

You have a statisticians blackboard view of numbers, i.e. “numbers is numbers”. You simply can’t seem to relate the numbers to physical reality. The number of digits in a result is only limited by the calculator! The real world of measurements simply don’t work that way!

ALGEBRA MISTAKE #33. A quotient (/) operator is not the same thing as a plus (+) operator.

An average is Σx divided by n. It is not Σx plus n.

And since Σx/n involves the division of Σx by n we use Taylor‘s Product & Quotient Rule 3.18 which states that δq/q = sqrt[ (δu/u)^2 + (δw/w)^2 ].

Let u = Σx and w = n and q = u/w = Σx/n

Assume δn = 0

(1) δq/q = sqrt[ (δu/u)^2 + (δw/w)^2 ].

(2) δ(Σx/n)/(Σx/n) = sqrt[ (δ(Σx)/Σx)^2 + (δn/n)^2 ]

(3) δ(Σx/n)/(Σx/n) = sqrt[ (δ(Σx)/Σx)^2 + (0/n)^2 ]

(4) δ(Σx/n)/(Σx/n) = sqrt[ (δ(Σx)/Σx)^2 + 0 ]

(5) δ(Σx/n)/(Σx/n) = sqrt[ (δ(Σx)/Σx)^2 ]

(6) δ(Σx/n)/(Σx/n) = δ(Σx)/Σx

(7) δ(Σx/n) = δ(Σx)/Σx * (Σx/n)

(8) δ(Σx/n) = δ(Σx) * 1/Σx * Σx * 1/n

(9) δ(Σx/n) = δ(Σx) * 1/n

(10) δ(Σx/n) = δ(Σx) / n

So when q = Σx/n (an average) then the uncertainty of q is equal to the combined uncertainty of the sum of the x’s divided by n such that δ(Σx/n) = δ(Σx) / n.

Fix your algebra mistake and resubmit for review.

The clown show continues, with the ruler monkeys in center ring.

bdgwx simply refuses to understand that the variance of a set of combined variables is the sum of the individual variances and not to the average value of the individual variances.

He can’t believe that the average uncertainty is *NOT* the uncertainty of the average.

Nor does he understand that the average is a STATISTICAL description and not a functional relationship! You can’t measure an average. An average is *NOT* a measurement, it is a statistical descriptor.

He’s lost in statistical world which apparently has no point of congruity with real world.

And that statistical sampling doesn’t apply to air temperature versus time, yet they hammer it in to the “standard error”.

They all refuse to sit down and learn the subject.

“Numbers is numbers!”

They are caught between a rock and a hard place when it comes to “standard error”.

Either they consider the data set to be a single sample in which case they have to *assume* a population standard deviation in order to calculate the standard error or they have to have multiple samples from which they can generate a standard error based on the CLT.

So who knows how accurate their “assumption” of a population standard deviation is if they count the data set as a single sample. That lack of knowledge of the population standard deviation adds measurement uncertainty which is additive to the SEM.

If they consider the data set to be a collection of multiple samples then the population standard deviation, the usual measure of measurement uncertainty is the SEM * sqrt(number of samples) – meaning the more samples they have the larger the measurement uncertainty becomes which is exactly what everyone familiar with metrology is telling them!

“Unskilled and Unaware”…

“ALGEBRA MISTAKE #33. A quotient (/) operator is not the same thing as a plus (+) operator.”

I didn’t state it so you could understand it I guess.

(Σx)/n is the average uncertainty.

It is *NOT* the uncertainty of the average.

Taylor’s product rule ONLY* applies to a functional relationship. The average is *NOT* a functional relationship, it is a STATISTICAL relationship.

I don’t know how many times Taylor Section 3.4 has to be repeated to you. If q = Bx then the uncertainty of q is ONLY RELATED TO THE UNCERTAINTY IN “x”. The uncertainty of B is zero.

There is no partial derivative of anything, only the relative uncertainties of q and x!

“So when q = Σx/n (an average) then the uncertainty of q is equal to the combined uncertainty of the sum of the x’s divided by n such that δ(Σx/n) = δ(Σx) / n.”

You are *still* trying to claim that the average uncertainty, u(x)/n, is the uncertainty of the average. It is *NOT*. Never has been and never will be. All this allows is using a common value times the number of elements to get the total uncertainty instead of having to add up individual uncertainties.

Again, the uncertainty of the average is related to the variance of the ENTIRE DATA SET, not just to the average variance of the individual elements in the data set. Averaging the variances of the individual elements will *not* give you the variance of the entire data set.

Var_total = Var_1 + Var_2 + …. + Var_n

Var_total is *NOT* (Var_1 + Var_2 +… + Var_n) / n

And it is Var_total that tells you the uncertainty of the average.

ALGEBRA MISTAKE #34:

(Σx)/n is not the average uncertainty. It’s not even an uncertainty. It’s just the average.

The average of the sample x is (Σx)/n.

The average uncertainty of the sample x is (Σδx)/n.

The uncertainty of the average of the sample x is δ((Σx)/n).

Fix mistakes #33 and #34 and resubmit review.

Wrong.

Look at the GUM 4.2

You say, the “average of the sample x is (Σx)/n”. It is not. If x is a sample, then it is a random variable with data points. The proper notation is x̅ = (1/n) Σxᵢ

The uncertainty is not δ((Σx)/n). The GUM says the SD is s²(xₖ) = (1/(n-1))Σ(xⱼ – x̅)².

The SDOM is s²(x̅) = s²(xₖ) / n

What is the Experimental Standard Deviation and the Experimental Standard Deviation of the Mean for that sample? That is how you calculate the uncertainty of the measurements in that sample.

ALEBRA MISTAKE #37

Contradiction of Taylor equation 2.3

δ is the symbol Taylor uses for uncertainty.

Therefore δ((Σx)/n) is the uncertainty of (Σx)/n.

You ran away from Jim’s question, clown.

No surprise.

Dude, you are cherry picking again with no knowledge of what you are picking. From Taylor:

Why don’t you read the whole damn book and work the problems.

“The uncertainty of the average of the sample x is δ((Σx)/n)”

This *IS* the average uncertainty!

It is *NOT* the uncertainty of the average!

Why can’t you address the fact that the uncertainty of the average is related to the variance of the total data set and not to the average variance of the data elements?

I’ll repeat:

Var_total = Var_1 + Var_2 + …. + Var_n

Var_total is *NOT* (Var_1 + Var_2 +… + Var_n) / n

And it is Var_total that tells you the uncertainty of the average.

Measurement uncertainty is treated exactly the same as variance.

You keep avoiding this basic fact for some reason. Is it because you *know* that the average uncertainty is *not* the uncertainty of the average but just can’t admit it?

ALGEBRA MISTAKE #36

Incorrect order of operations – PEMDAS Violation

δ is the symbol Taylor uses for uncertainty. See equation 2.3 on pg. 13.

(Σx)/n is formula for the arithmetic mean. See equation 4.5 on pg. 98.

Parentheses () are used to indicate operations that should occur first.

Using PEMDAS the expression δ((Σx)/n) means the uncertainty δ is of the quantity in the outer parentheses group just to the right. The quantity in this parathesis group is formula for the average. Therefore δ((Σx)/n) is the uncertainty of the average.

Here is a lesson on order of operations.

bozo-x doubles-down on his clown show.

I *KNOW* what Taylor uses to indicate uncertainty.

Do it terms that the GUM uses:

Let y = x1 + x2 + … +xn

The average uncertainty, u_avg(y) is thus the sum of the uncertainties of the elements of y

If the uncertainties are such that direct addition should be used then

u_avg(y) = [ u(x1) + u(x2) + … + u(xn) ] /n

If you want to do it in quadrature then you

u_avg(y)^2 = u(x1)^2 + u(x2)^2 + …. + u(xn)^2

THESE ARE AVERAGE UNCERTAINTY. Nothing more. They are *NOT* the uncertainty of the average.

The uncertainty of the average is the variance of the data elements. The higher the variance the less certain the average value becomes.

Var_total = Var_1 + Var_2 + … + Var_n

This is *exactly* the same as saying

u(ty) = u(x1) + u(x2) + …. + u(xn) as showed above.

There is *NO* division by “n” when using either the variance or the measurement uncertainty.

u(x1) to u(xn), the uncertainties of the x data elements, can be either the direct measurement uncertainty of single measurements of different things using different measurement devices or can be the variance of the a set of data from multiple measurements of the same thing using the same device.

For either case the uncertainty of the average is based on the dispersion of possible values that can be assigned to the average. That dispersion grows as more and more uncertain data elements are added into the data set. The uncertainty of the average is *NOT* the average uncertainty which you continue to try and rationalize to yourself – and which you continue to fail at.

And once again, all they can do in reply is hit the red button.

Nowhere does Dr. Taylor define uncertainty this way.

Quit cherry picking. Here is what Dr. Taylor defines as uncertainty.

Here are the correct equations from the book.

You definition is missing how to calculate σₓ or σₓ̅.

Let’s examine Dr. Taylor’s Eq. 3.18 more closely. Here is an image of the pertinent page.

As you can see, the functional relationship is:

q = (x • y • z) / (u • v • w)

Where the relative uncertainties from both the numerator and denominator add together in quadrature.

Now let’s see what you have done.

The “Σx” is not a good descriptor. It should be:

Σxᵢ

This depicts “x” as a random variable with some number of “n” entries.

The mean “μ” of a random variable is “Σxᵢ / n”. And

q = μ

The experimental standard deviation of “μ” is a well known calculation as is the experimental standard deviation of the mean.

Now, let’s examine your algebra.

With δn = 0, Eq 1 becomes,

(1) δq/q = √[ (δu/u)² + (0/n)² ] = √((δu/u)²)

Remember w = n, so if δn = 0, then δw = 0.

Now, how about Eq 2

(2) δ(Σx/n)/(Σx/n) = sqrt[ (δ(Σx)/Σx)^2 + (δn/n)^2 ]

Same result as Eq 1

(2) δ(μ)/(μ) = √((δ(μ)/ μ)² + (0/n)²) = √((δ(μ)/μ)²)

Everything that follows is superfluous!

Here is your problem.

From the GUM:

Where the other quantities are unique measurements that are combined through a functional relationship. Your insistence on using a mean as a measurement provides you with ONE single “X” measurement. That is,

Y = X₁

You can not dodge the fact that the values form a random variable and that the μ and σ of the random variable are the approriate values being derived from that random variable.

In your terms, Y = X₁ = μ = q = u/w = Σxᵢ/n

ALGEBRA MISTAKE #35

Incorrect variable substitution.

Taylor 3.18 says δq/q = sqrt[ (δa/a)^2 + (δb/b)^2 ] when q = a/b

If q = μ = a/b = Σx/n

Then per Taylor 3.18 δμ/μ = sqrt[ (δ(Σx)/Σx)^2 + (δn/n)^2 ]

However, you wrote δμ/μ = sqrt[ (δμ/μ)^2 + (0/n)^2 ] which is wrong.

Here is a lesson on how to use substitution to solve algebra equations. One tip that you might find helpful is to surround the variable to be substituted with () first and then put your substitution expression inside the parathesis.

To review:

#33 – Do not treat a quotient (/) like addition (+) when selecting a Taylor rule.

#34 – Do not confuse the average of a sample with uncertainty.

#35 – Do not incorrectly substitute an expression into variables of a formula.

Fix mistakes #33, #34, and #35 and resubmit for review.

Here is what you wrote.

Note the w = n

Therefore, δw = δn = 0

Consequently, (δw/w)² = (0/w)² = 0

Same problem with EQ 2. You said “Assume δn = 0”, not me. Therefore, (δn/n)^2 = (0/n)² = 0

Perhaps you should learn how to substitute properly.

Better yet perhaps you should learn what a random variable is, what a mean of a random variable is, what the SD and SDOM of a random variable.

Perhaps rereading TN 1900 Example 2 will help in understanding what these are.

You also need to learn what repeatable conditions and reproducibility conditions are and what dispersion of measurements values are used for each

Are you going to fix the algebra mistakes or not?

Are you going to learn anything about the subject or not?

You are a condescending fool who doesn’t know WTF you yap about, which includes your goofy ideas about thermodynamics.

The uncertainty of the average is *NOT* the average uncertainty, it is the dispersion of values that can be assigned to the average.

That dispersion of values that can be assigned to the average is *NOT* the average dispersion of each individual data element, it is the SUM of the dispersions of the individual data elements.

Why you continue to advocate that the uncertainty of the average is the average uncertainty is simply beyond understanding.

Even a first year business student learns in their first statistics course that a distribution has to be described by *both* the average and the standard deviation and not just by the average itself. Yet you, and climate science, continue to try and justify that the standard deviation can just be ignored, that it has no bearing on the uncertainty of the average.

Yes. LINEST does not allow an analysis of data that has an associated measurement uncertainty.

I get this as the second order coefficient, which I misidentified in my other comment. But wouldn’t the actual acceleration be twice that? And if so, then it’s standard error would require it to be reported as 0.006 C per decade squared, right?

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2024/09/02/uah-global-temperature-update-for-august-2024-0-88-deg-c/#comment-3964129

Yep. I get 0.00000037 C.month-2 which is 0.0054 C.decade-2 and should be reported as 0.005 C.decade-2 as the standard deviation per Tim’s rule. Note that the discrepancy between 0.005 and 0.006 may be due to rounding errors possibly caused by me using the 3-digit file. And per Tim’s rule since the standard deviation’s first digit is at the 3rd decimal place we set the significant figures of the value in question with the last digit at the 3rd decimal place so it is 0.028 C.decade-2.

I think the real question is whether you should set your significant figures based σ or 2σ. I prefer 2σ myself which would suggest 0.03 C.decade-2 as the best presentation and as I recommended doing here for WUWT’s dedicated UAH page.

I might also not be perfectly using your data set. I used the same source, but a month here, a month there…

As for the inclusion of +/- 0.2 C/month in the eval, there must be an elegant way to do it. Instead I;

Yeah, that’s how I would do it too. I think a Monte Carlo simulation like you specified is probably the easiest way.

This is a SAMPLING ERROR, not a measurement error. They admit they have no way to determine how the clouds actually impact their measurements during a scan so they “parameterize” a guess, just like all climate science does. And who knows what the actual accuracy of that guess is?

The massive amount of water injected into the stratosphere by the historic Hunga Tonga eruption (15 Jan 2022) has been suggested as a possible source for added warming. Yet most publications to date suggest Hunga Tonga water vapor will cause only slight warming. However, these new data show that some of the warmest temperatures occurred in the southern hemisphere, which is where most of the Hunga Tonga water vapor resides.

Looks like an unusual stratosphere event..

Record 50C temperature increase over Antarctica to shift Australia’s weather patterns – ABC News

El Nino warming usually escapes through the polar regions…

… not happening quickly this El Nino, possibly because of the HT moisture.

Maybe it escapes through your brain?

You poor thing.

Exposing your ignorance yet again.

Hilarious that you don’t know that energy mostly comes in in the tropics and out through the polar regions.

It couldn’t escape through your brain.. because you don’t have one.

I was just looking for reasons why you become so heated.

Too much laughter at your ignorance and incompetence.

HT water vapour blocking high latitude cooling…

Could do so for a while longer.

Even a ignorant monkey like you should understand that…

Glad to see that you are still around.

“The massive amount of water injected into the stratosphere by the historic Hunga Tonga eruption (15 Jan 2022) has been suggested as a possible source for added warming.”

And this injection of water into the upper atmosphere may have another effect on the Earth’s weather as the eruption supposedly disrupted the ozone layer, and the ozone layer has a lot to do with how the weather unfolds here on the Earth.

Some people argue the water vapor itself, and a greenhouse effect therefrom, is not sufficient to account for the increased warmth, but maybe a disruption of the ozone layer is.

Ozone is not getting enough discussion in this matter, imo.

Completely agree. The claim is that chlorine from salt water injected into the stratosphere reacted with ozone. Since ozone reduces high energy UV this should have a warming effect. In addition, the additional UV might be reducing cloud condensation nuclei which would generally reduce clouds having a secondary warming effect.

It was 150 MtH2O. To put that into perspective since the HT eruption about 50000 MtCO2 accumulated in the atmosphere.

The 150 MtH2O that went into the stratosphere is dispersed globally now.

Another person who doesn’t understand how saturation affects the GHE.

Among many, many other topics.

Here is the Monckton Pause update for August. At its peak it lasted 107 months starting in 2014/06. Since 2014/06 the warming trend is now +0.40 C/decade.

Here are some more trends over periods of interest.

1st half: +0.14 C.decade-1

2nd half: +0.23 C.decade-1

Last 10 years: +0.39 C.decade-1

Last 15 years: +0.37 C.decade-1

Last 20 years: +0.30 C.decade-1

Last 25 years: +0.22 C.decade-1

Last 30 years: +0.18 C.decade-1

The warming rate acceleration is now +0.028 C.decade-2.

Over on the dedicated UAH page here on WUWT it says “This global temperature record from 1979 shows a modest and unalarming 0.14° Celsius rise per decade (0.25⁰ Fahrenheit rise per decade) that is not accelerating.”

As noted above the trend is now +0.16 C.decade-1 and the acceleration is +0.03 C.decade-2. The page probably needs to be updated to reflect the current state of the UAH dataset.

But it won’t be.

The ongoing El Nino/HT event is really getting you all hot and bothered, isn’t it little boy.

Now.. do you have any evidence whatsoever for any human causation??

Spencer an Christy themselves said HT added “at most” hundredths of a degree to the UAH global surface temps – and that was at the time, over 2 years ago.

Poor muppet.. they made a guess, with all the weak words like could, assume, etc etc.

Seems they made a bad guess.

Let’s try again, watch you squirm and slither …

Do you have any evidence whatsoever for any human causation??

Now you know better than Spencer and Christy of UAH.

Is there any beginning to your talents?

All you have to do is look at the data.

Obviously that is beyond your capabilities.

Now, still waiting for evidence of human causation

Watching you squirm like a slimy little worm is hilarious. 🙂

You mean the data showing 14 consecutive warmest months, including 3 (to date) that occurred after the El Nino ended and over 2 years since the HT eruption?

Oh, I’m squirming, lol!

It’s pointless. It’s been posted here so many times that it’s clear that you just don’t understand it.

Even your ‘heroes’ here; Spencer, Christie, Lindzen, Happer, et al; they all accept a human influence on climate change.

Every single one of them.

Just because you don’t understand something doesn’t mean it’s not true.

You have never posted a single bit of evidence.

It is obvious that you don’t understand the difference between non-scientific propaganda and actual science.. and never will.

Look at you squirming yet again trying to pretend you do.

You have NO EVIDENCE of human causation. period.

Don’t expect any. That may have something to do with the fact that there isn’t any.

All that does is show there have been 14 consecutive warmest months.

Fairies on a pin head.

Is there any end to your feebleness?

Poor thing….. fungal has so little talent that he wouldn’t even get the part of a worm in a muppet show.

Spencer and Christy don’t know any more than anyone else what’s happening.

They provided an early order of magnitude estimate of the influence of Hunga Tonga. It seems to me that the historical observations strongly suggest revisiting the question.

Lol.

And based totally on El Nino events.

Which he knows have zero human causality.

Don’t forget Monckton’s favourite pause of all time !! He referred to it in such loving terms, you could imagine it was a real person.

It started in 1997, and ran until 2015. The start month which has always had the lowest warming trend (or during the pause, the greatest cooling trend) was December 1997.

February 2016 was the first month when he could no longer write his “Great Pause” articles. The warming rate according to the UAH data from December 1997 to date is now 0.17 degC/decade, slightly higher than the rate for the whole dataset (0.16)

I wonder how involved he’ll be in reporting on the next pause.

Does the higher temperatures in the UAH indicate more heat loss from the planet? That would be consistent with the lousy summer here on BC west coast.

Yeah, no record heat at my house. It was a fairly mild, pleasant summer around here. I would take a summer like this one every year. Not too hot, and just enough rain to keep things green. Now the hottest part of the year is over and we cool into fall. Life is Good!

Calling El Nino Nutter BeNasty2000

Calling El Nino Nutter and website Court Jester BeNasty 2000

After a year of dominance, El Niño released its hold on the tropical Pacific in May 2024, according to NOAA’s latest update.

The 2024 El Nino ended in May 2024 but the UAH temperature anomaly has barely changed. That could not happen if your El Ninos Cause All Global Warming Claptrap Theory was correct.

Your El Nino theory fell apart like a cheap suitcase.

How about a new theory?

How about an old theory? Climate is a complex, coupled, semi-chaotic system that is poorly understood, and attempting to peg any single simplistic factor as “the Cause” is both futile and juvenile. No one knows, and name-calling will not change that fact.

Exactly. One thing we can all agree on is that it wasn’t CO2 wot did this.

You still think this isn’t part of the El Nino / HT event…. how quaint ! 🙂

You probably think human CO2 caused the temperature to stay high in the southern hemisphere or something dumb like that…

Down here, the last week or so of August has been unusually warm for sure.. GORGOEOUS weather.

There was also some sort of “event” in the stratosphere at that time…

… obviously human CO2 as well. 😉

This latest UAH warmest monthly temperature record, the most recent of the past consecutive 14, is global, not just Australia.

You’ve completely run out of road, mate.

You’ve continuously said this was all down to El Nino, which ended months ago. You’re a busted flush.

Monthly warmest global and regional temperature records continue to be set in UAH, many months after the El Nino ceased to be a factor.

And to think, UAH, once so beloved of WUWT. Et tu Brute?

Oh, the tragedy of it all!

You STILL haven’t shown anything remotely scientific for human causation of the recent EL Nino.

It is a travesty 😉 You are off-road without any wheels.

And really quite hilarious watching you faff-about in complete ignorance.

It is obvious to even a blind that the current slight warming is still part of the extended El Nino event..

Or do you have some evidence that humans are somehow stopping the El Nino warming from dissipating.

We are still waiting.

You are FAILING utterly and completely

fungal and RG.. a new bedwetting fellowship.

This spike was all down to heat being released from the oceans, That it is persisting is partly due to averaging with SH heat (again from the sea) and probably partly from the HT eruption however no one (including you) knows. Just what is your point here?

Human caused [lol] sudden stratospheric warming over the Antarctic.

Record 50C temperature increase over Antarctica to shift Australia’s weather patterns – ABC News

IS this something from the HT event ?

Even the dumbest person in the world couldn’t put it down to human CO2…

…. but I’m sure you will try.

A flurry now with “sudden stratospheric events” rather than just admit that you were/are wrong.

It dies hard in some.

You can continue to be IGNORANT of what is actually happening, and the real cause for this months SH warming.

You can continue to be IGNORANT of the persistent El Nino effect.

Or you can continue to “imagine ” some sort of fantasy human causation.

Again, averaged nonsense. The Pacific Northwest has been cool for three months.

Not for June and July according to UAH.

Here is weather data I collected from southeastern New Hampshire.

April 2002 exhibited a highly dynamic and volatile temperature profile. The spread of temperature shows a lack of stability, with both early and late spring characteristics present, making the month feel unpredictable.

In contrast, April 2022 exhibited a consistent and stable temperature pattern, with less pronounced fluctuations. Temperatures indicate a more predictable and steady progression of spring. The consistency in temperature can lead to a smoother transition between seasons, making it easier for ecosystems and humans to adapt.

In both months, the same average would suggest similar climatic conditions, yet the day-to-day experience of weather was markedly different. Furthermore in subsequent calculations such as the yearly average, these months’ averages would contribute equally to the overall result.

There is a lack of physical representation. The monthly mean only reflects the central tendency of the temperatures recorded throughout the month.

Here is the minimum temperature spread for both months. An interesting observation from 2002 is that the minimum temperature range is more compressed than the maximum range.

This could suggest clear skies during the day and cloudier conditions at night, which would prevent all the heat absorbed by the ground during the day from radiating back into space. It’s another detail that gets obscured.

Nighttime temps are an exponential (or at last a polynomial) decay that is asymptotic. As the temp drops you get less and less radiation which means less change per unit time in the minimum temps. This leads to compressing the minimum temps. That’s not to say that’s the only factor, certainty the clouds figure in but probably more as a modifier to the decay constant than as a heat source.

Is that on the ground? No.

No, it’s the lower troposphere satellite data. The data you were describing as averaged nonsense.

Here’s the NOAA map for June and July, anomalies based on the 20th century average.

Introducing the Hungatongameter. It’s the global sea surface temperature (NOAA 60°N-60°S, baseline 2021). Volcanic-induced warming starts in Dec 2022, peaks at +0.5°C in Jan 2024, and has cooled by 52% since then. Global temperatures should follow with a lag of a few months.

The UAH monthly averages of global LAT show three consecutive months of rising temperatures (June, July and August). June was five months after Jan 2024.

JV – did you try SH only? Preferably SH extratropical only, since the tropics have a SST stabiliser (as per w.e.). [I’m travelling with phone only so can’t do it myself]

Every month I think this must surely be the point where satellite temperatures start to drop, but looks like we’ll have to wait another month at least.

This is the warmest August in the UAH data, 0.18C warmer than the previous record set last year, which was itself 0.31C warmer than the previous record.

The top ten warmest Augusts

Unless something really dramatic happens in the next few months, 2024 will smash the 2023 record year.

Satellite data does seem to be lagging surface data.

Here is what NASA Goddard itself has to say about GISTEMP, verbatim from https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/faq/ :

“The GISTEMP analysis recalculates consistent temperature anomaly series from 1880 to the present for a regularly spaced array of virtual stations covering the whole globe.”

(my bold emphasis added)

That’s all anyone with an IQ above room temperature needs to know.

It takes real chutzpah to compare UAH data to GISTEMP calculations.

The bellboy still hasn’t figured out that the atmosphere responds a lot more to major El Nino events than the land surface does.

Sort of like watching a parrot hanging upside down on a clothesline.

“It takes real chutzpah to compare UAH data to GISTEMP calculations.”

You do realise there are quite a lot of calculations involved in UAH?

Yes, of course, but UAH (Dr. Christy and Dr. Spencer) start with instrumental hard data measurements instead of “a regularly spaced array of virtual stations”.

ROTFL.

“ “a regularly spaced array of virtual stations”.”

ie TOTALLY FAKE !!

UAH does the same thing. Except they have 10368 “virtual stations” of which only 9504 are analyzed. The other 864 are assumed to behave like the average of the 9504. And of the 9504 that are analyzed they have to interpolate the majority of them using neighbors up to 4165 km away.

[Spencer & Christy 1992]

You apparently don’t understand that the mathematics of “binning” data is not at all the same as actually obtaining data from those separate “bins”.

Good grief!

“binning” and “virtual stations” are synonymous. In the same way that GISTEMP has 8000 “virtual stations” UAH has 10368 “virtual stations”.

And here is how UAH has changed over the years.

Year / Version / Effect / Description / Citation

Adjustment 1: 1992 : A : unknown effect : simple bias correction : Spencer & Christy 1992

Adjustment 2: 1994 : B : -0.03 C/decade : linear diurnal drift : Christy et al. 1995

Adjustment 3: 1997 : C : +0.03 C/decade : removal of residual annual cycle related to hot target variations : Christy et al. 1998

Adjustment 4: 1998 : D : +0.10 C/decade : orbital decay : Christy et al. 2000

Adjustment 5: 1998 : D : -0.07 C/decade : removal of dependence on time variations of hot target temperature : Christy et al. 2000

Adjustment 6: 2003 : 5.0 : +0.008 C/decade : non-linear diurnal drift : Christy et al. 2003

Adjustment 7: 2004 : 5.1 : -0.004 C/decade : data criteria acceptance : Karl et al. 2006

Adjustment 8: 2005 : 5.2 : +0.035 C/decade : diurnal drift : Spencer et al. 2006

Adjustment 9: 2017 : 6.0 : -0.03 C/decade : new method : Spencer et al. 2017 [open]

That is 0.307 C/decade worth of adjustments jumping from version to version netting out to +0.039 C/decade. And that does not include the adjustment in the inaugural version.

Every one of them for a known scientific reason.

As opposed to the agenda-driven fabrications and urban warming in the highly random surface data.

Pity the AGW cultists choose not to understand the difference.

Actually these just reflect the 20+ different satellites with different orbits etc. that NOAA has used over the years; bgx likes to prop up Fake Data fraud by pulling these numbers out and equating them.

Totally false.

They don’t even compensate for the variances of the data generated by each satellite. How do you jam data sets with different variances together to form an average without weighting the data in some manner?

Easy, ignore them.

Variances are ignored and dropped starting from Average Number One. They don’t even report the number of points in their averages!

Get back to me when you realize just how laughable it is to assert that a slope of GLAT temperature change per decade can be calculated to a precision of three decimal places (i.e., “0.307 C/decade”).

I’m going to tell you what I tell everyone else. I’m not going to defend your arguments especially when they are absurd.

Your whole argument is ABSURD. !

That has never stopped you before. !

Oh, you totally misunderstand (once again) . . . I never asked or implied that you should “defend” my arguments . . . only that you realize how wrong some of yours are.

I’m not the one who presented the argument that the slope of the temperature can be calculated to a precision of 3 decimal places. You are the one that first presented that argument; not me.

And for the record my position is that the uncertainty on the UAH trend is ±0.05 C.decade-1 through 2023. This is what I get when I use an AR(1) model. It might be interesting note that [Christy et al. 2003] assess the uncertainty on the trend as ±0.05 C.decade-1 through 2002 while an AR(1) model assess it as ±0.1 C.decade-1 over the same period.

It is quite obvious, for the nth time, that you simply don’t understand things you are commenting on.

In the post of mine that you referred to, I clearly stated:

“Get back to me when you realize just how laughable it is to assert that a slope of GLAT temperature change per decade can be calculated to a precision of three decimal places (i.e., “0.307 C/decade”).”

Yet, you call that presenting “the argument that the slope of the temperature can be calculated to a precision of 3 decimal places.”

Again, just laughable!

Yep. The first mention of this argument was by you here. Remember, you wanted me “Get back to me when you realize just how laughable it is to assert that a slope of GLAT temperature change per decade can be calculated to a precision of three decimal places (i.e., “0.307 C/decade”)” My posts here and here were me doing what you requested.

I know. That’s what I’m trying to tell you. And if you’re this upset by it then maybe you shouldn’t have presented the strawman argument that the slope of the temperature can be calculated to a precision of 3 decimal places in hopes that I would defend it.

Now, we can either go back and forth with this absurd argument of yours that the slope of the temperature can be calculated to a precision of 3 decimal places or we can continue down a more productive path of discussing what UAH actually does and what they say the uncertainty actually is. Like I’ve said before I grew weary quickly of telling people I’m not going to defend their absurd arguments so my vote is for the later path.

Upset? . . . only by dint of outright laughter.

The trendologists have penchant for projection.

Just laughable!

In fact, as all readers are free to see, among all the comments under the above article, the very first mention of a slope of 0.039 C/decade (i.e., a slope to three decimal places) was made by you in your post of September 2, 2024, 2:57 pm wherein you argued:

“That is 0.307 C/decade worth of adjustments jumping from version to version netting out to +0.039 C/decade.”

Yes they are.

Yep. And I stand by that statement. The net change of all adjustments as reported by Spencer and Christy is 0.039 C/decade.

Notice that I didn’t say that the warming rate as computed by UAH had a precision to 3 decimal places. You said that. All I said was that the net effect of all adjustments was 0.039 C/decade. And it is 0.039 C/decade regardless of whatever uncertainty exists for their warming rate calculation whether it is ±0.05 C/decade like what they report through 2002 or the ±0.1 C/decade which I assess over the same period. It doesn’t matter. They still changed their reported warming trends by 0.039 C/decade. No more. No less.

BTW…you can see that I report the AR(1) uncertainty here long before this discussion and it does not suggest a precision down to 3 decimal places.

bdgwx posted:

“The net change of all adjustments as reported by Spencer and Christy is 0.039 C/decade.

Notice that I didn’t say that the warming rate as computed by UAH had a precision to 3 decimal places.”

If there’s anyone—anyone at all—that can explain those two back-to-back sentences, please get in touch with me.

Meanwhile, ROTFL.

TYS,

You’re probably blue by now. Some folks here have a problem counting decimal places and significant digits.

I don’t mind clarifying if it will help. What specifically does not make sense about those two statements?

“0.039 C/decade”

“Notice that I didn’t say that the warming rate as computed by UAH had a precision to 3 decimal places.”

Accuracy: how close a measurement comes to the true value

Precision: how reliably a measurement can be repeated over and over

Resolution: The smallest increment an instrument can display

You *still* haven’t figured out what accuracy, precision, and resolution *are* in metrology.

Precision and resolution, while related, are *NOT* the same thing.

The general rule in metrology is that the last significant digit in any stated value should be in the same decimal place as the uncertainty.

That means that the measurement uncertainty associated with 0.039 C/decade would be in the thousandths digit. This is absurd. There isn’t a temperature measurement station of any type used in any system today that has a measurement uncertainty in the thousandths digit.

(the fact that PTR sensors have a resolution in the thousandths digit is *NOT* a factor in the station measurement uncertainty)

As far as I know there isn’t a temperature measurement system in use today that even has a measurement uncertainty in the hundredths digit let alone the thousandths digit.

This means that there is no way to determine a decadal difference in the thousandths digit. The decadal difference would have to be in the tenths or units digit in order to be actually identified.

This is just one more example of climate science using the memes of 1. all measurement uncertainty is random, Gaussian, and cancels so that the stated values can be considered 100% accurate and 2. numbers is numbers and don’t need to have any relationship to reality.

No it isn’t. Nor is it the measured warming rate of UAH either.

Consult with your brother on this one. He was able to correctly identify what this value is.

“Numbers is numbers”…

Yes it is. Anything that is posed as a quantity is a measurement.

Look at NIST TN1900 Ex 2. Look what it concludes.

The mean is a measurement. The uncertainty is a measurement. The interval is a measurement. Anything calculated from measurements, including trends, are also a measurement.

Are you sure? I ask because earlier you said it was a correction.

If you are sure can you 1) cite where UAH “measured” a warming rate of 0.039 C/decade so that I can review the citation to confirm that it really does confirm your assertion and 2) explain what caused you to change your mind?.

I think the problem is between your ears.

Doesn’t matter. A correction is a measurement also. Or, didn’t you know that?

“stated value +/- measurement uncertainty

MEASUREMENT UNCERTAINTY

The measurement uncertainty has the same dimension as the stated value.

E.g. 3″ +/- 1″

That value of 1″ *is* a measurement. To know what it is you have to MEASURE it.

That’s definitely new one.

So when you and/or Tim commit algebra mistake #38 and leave the left hand side of the equation as δq/q instead of solving for δq by multiplying both sides by q then I’m taking a “measurement” when I correct your mistake and report the difference between the correct answer and the right answer?

Also, where is the citation where UAH reported a warming rate 0.039 C/decade?

Only because you don’t know anything about metrology.

You think you do, but you don’t.

Not if you know how correction tables and functions are actually made.

Have you ever used a gauge block?

Have you ever used one to create a correction tables for an instrument? It sure doesn’t sound like you have!

You *still* don’t understand what a functional relationship is!

If C = A – B then you measure A and B in order to find C.

E.g. the area of a rectangle is length (A) times width (B) = C (area)

That makes C a measurement of the property of the rectangle, i.e. the area!

temperature per time *IS* a rate.

From Merriam-Webster:

“1 a

: a quantity, amount, or degree of something measured per unit of something else

C/decade is no different than miles/hour. Now tell us how miles/hour is not a “rate” either!

“And for the record my position is that the uncertainty on the UAH trend is ±0.05 C.decade-1 through 2023. This is what I get when I use an AR(1) model. It might be interesting note that [Christy et al. 2003] assess the uncertainty on the trend as ±0.05 C.decade-1 through 2002 while an AR(1) model assess it as ±0.1 C.decade-1 over the same period.”

These are *NOT* measurement uncertainty which is what should be used to determine the significant figures used in the data.

These figures are “best-fit” metrics calculated from the residuals developed from assuming the data is 100% accurate and calculating the difference between the assumed 100% accurate data and the linear regression line out to several decimal digits not supported by the actual data.

It’s just one more use of the common meme of climate science that “all measurement uncertainty is random, Gaussian, and cancels”.

Never forget this is the guy who thinks the door of a convection oven heats the inside of the oven!

Those are “corrections”. Corrections are used to reduce known errors in the measurement definition, measurement procedure, and measurement device. They are not measurement uncertainty. From the GUM.

It is difficult to precisely discuss measurement uncertainty without an accurate uncertainty budget that has been carefully developed. Items like repeatability, reproducibility, drift, calibration, resolution, etc.

You might try admitting that climate science ignores much of the measurement uncertainty and it’s propagation throughout calculations.

“UAH data to GISTEMP calculations”

UAH does exactly the same. You have a lot of observations, and you need a numerical integral to get the average. Almost everyone does that by first estimating the values on a regular grid.

Here are Spencer and Christy describing just a small part of the process of assembling their “data “, including gridding:

““The LT retrieval must be done in a harmonious way with the diurnal drift adjustment, necessitating a new way of sampling and averaging the satellite data. To meet that need, we have developed a new method for computing monthly gridpoint averages from the satellite data which involves computing averages of all view angles separately as a pre-processing step. Then, quadratic functions are statistically fit to these averages as a function of Earth-incidence angle, and all further processing is based upon the functional fits rather than the raw angle-dependent averages.”

Good grief . . . you too???

It isn’t a matter of binning. As S&C describe, you have one satellite in the sky. It can’t be vertically over every point. It has signals coming in from all sorts of angles, at all local times of day. They have to interpolate that in 3D, not 2D, to get estimates on a 3D grid (virtual stations). They have to adjust for local time diffreence. Then they have to do a weighted sum in the vertical to get LT, MT etc.

Actually, that is not at all what Dr. Spencer and Dr. Christy describe.

Here, read it in their own words, under their names, in their updated report Global Temperature Report: July 2024 available at https://www.nsstc.uah.edu/climate/2024/July/GTR_202407JUL_v1.pdf :

“Dr. Christy and Dr. Roy Spencer, an ESSC principal scientist, use data gathered by advanced microwave sounding units on NOAA, NASA and European satellites to produce temperature readings for almost all regions of the Earth. This includes remote desert, ocean and rain forest

areas where reliable climate data are not otherwise available.”

and

“There has been a delay in our ability to utilize and merge the new generation of microwave sensors (ATMS) on the NPP and JPSS satellites, but we are renewing our efforts as Dr. Braswell is now focused on this task.”

One satellite???

Also, microwave sounding instruments on orbiting spacecraft usually process signal returns that are restricted to the satellite’s nadir point (to minimize path length and reflection errors) so your comment “It has signals coming in from all sorts of angles . . .” is just plain wrong.

From Wiki

“The AMSU instruments scan continuously in a “whisk broom” mode. During about 6 seconds of each 8-second observation cycle, AMSU-A makes 30 observations at 3.3° steps from −48° to +48°. It then makes observations of a warm calibration target and of cold space before it returns to its original position for the start of the next scan. In these 8 seconds the subsatellite point moves about 45 km, so the next scan will be 45 km further along the track. AMSU-B meanwhile makes 3 scans of 90 observations each, with a spacing of 1.1°.”

That is what they have to turn into a 3D grid, as Spencer and Christy describe. It has signals comping in “from −48° to +48°”.

Regular and predictable and not affected by random air-conditioners and tin shed.

Sorry if the concept is too complicated for you nowadays.

Yes, that describes the sounding instrument scanning process, but the real question (that you left unanswered) is what part of that scan is used to actually derive the inferred LAT temperature that is recorded for the satellite’s instantaneous latitude and longitude. Check it out and I think you’ll find that it is only the data that is localized to the spacecraft’s nadir direction, which itself is revealed to high accuracy by the scan itself.

BTW, Wiki has it wrong (is that surprising to anyone???): between each 8 second-cycle of thirty observations between −48° to +48° AMSU-A does not always observe “a warm calibration target” . . . those calibration targets are located on land—where their temperatures over time can be accurately recorded for later use during data reduction calculations for the various spacecraft sounding units used by UAH. Such spacecraft often overfly and obtain data for large sections of oceans, for tens of minutes, where there are no calibration targets.

“Check it out and I think you’ll find that it is only the data that is localized to the spacecraft’s nadir direction”

It can’t be. One satellite, or even a few, can’t scan enougn area that way.

Here is Spencer’s diagram that went with the quote I gave above, The inset shows how they take a result, not from the nadir value alone, but from a weighted sum of all the angles.

Anyway, the real point is that this is all a great more calculation than goes into a surface calculation like GISS.

Here are the dimensions of the scanning footprints.

And here is the aggregate coverage over a two day period. Notice that the coverage is poor; even worse than traditional surface station datasets over the same period.

[Spencer et al. 1990]

Nick Stokes posted: “The inset shows how they take a result, not from the nadir value alone, but from a weighted sum of all the angles.”

No, the scanning figure provided by bdgwx does not show that . . . it only shows how the scanned areas from -47.34° (left) to +47.34° (right) of the satellite’s ground track vary based on 3db (signal return) “footprints”.

In particular, note the figure title statement that “Angular dimensions of 7.5° and 9.47° refer to the antenna 3 dB beamwidth and along-scan footprint spacing, respectively” (my bold emphasis added). This directly implies that only those three scanned spots (limited to less than 13 degrees off spacecraft nadir) are used in final data processing.

You provide a graphic of only two days coverage from only a single satellite (NOAA-7) to support your claim that UAH GLAT data measurement is “poor; even worse than traditional surface station datasets”.

How about providing a similar plot that includes the data from all seven or so satellites (in various orbits) that UAH incorporates AND that includes 30 or so days of sampling used by UAH to calculate the monthly-average GLAT that it reports.

First…remember that the graphic Nick posted is produced by the same person that produced the graphic I posted. Second…yes it does.

I encourage you to read the methodology publications published by Dr. Spencer and Dr. Christy. It would be beneficial to do this before commenting that you way you are commenting on what they actually do as opposed to what you thought they did

Yep. And that’s all it takes to support my position. Note that over any 2 day period in the GISTEMP every single one of their “virtual stations” has at least 4 observations. Contrast this with UAH where vast swaths of their “virtual stations” have no observations at all.

It’s a good idea. Unfortunately [Spencer et al. 1990] only includes one such graph.

Ummmm . . . 1990 was more than 30 years ago!

Yep. And 1978 was over 40 years ago. It doesn’t really matter since sun synchronous polar orbits aren’t any different today than they were 40 years ago.

Polar orbits are not material objects . . . they are mathematically described constructs. Therefore, your statement “sun synchronous polar orbits aren’t any different today than they were 40 years ago” is true but has zero practical meaning.

Sorta like saying “1+1=2” isn’t any different today than it was a thousand years ago.

The point is that a satellite orbiting in 1978 has the same coverage as one orbiting in 1990 or 2024. So insinuating that Dr. Spencer’s graphic is irrelevant today because it is 30 years old is erroneous.

He conveniently ignores the fact that “polar orbits” degrade over time so they are not constant.

“Observations” from virtual stations . . . sounds like something that might exist in a virtual universe with virtual science.

I’ll let you pick that fight with Dr. Spencer and Dr. Christy on your own.

(Sigh)

I have NO disputes with Dr. Spencer and Dr. Christy . . . in fact, I admire their work and dedication to science, both inside and outside of their association with UAH.

It is the folks over at Goddard that are way off base in asserting that “virtual stations” are meaningful things.

Dr. Spencer and Dr. Christy assert that “virtual stations” are meaningful things too.

Prove it.

I posted their methodology bibliography below. They are unequivocal on the fact that they use a 2.5×2.5 degree grid in which observations are assigned.

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2024/09/02/uah-global-temperature-update-for-august-2024-0-88-deg-c/#comment-3963348

Ummmm . . . in science, that would commonly be called “binning” or “mapping” scanned scalar data onto a 3D surface (in this case, one representing Earth’s surface).

What you continue to fail to recognize is that is assigning data to its appropriate geographical location (to a N-S and E-W error box of ±1.25 degrees each direction) . . . which is totally different from stating that data is obtained from gridded “virtual stations”.

In the case of UAH, such mapping of data is apparently part of their process of being able to conveniently calculate global average LAT by geographically weighting individual MSU scan retrievals based on the total values accumulated in each grid box in the course of one month’s data collection. I emphasize “apparently” because I don’t know for a fact how UAH computes a single value for GLAT using thousands (millions?) of scan retrievals from MSUs on numerous satellites in polar orbits around Earth.

BTW, I asked for a proof that Spencer and Christopher “assert that virtual stations are meaningful things”, not a bibliography listing of UAH methodology. Big fail on your part there.

It’s not any different. That’s what GISTEMP does. Their “virtual stations” are the 8000 grid cells in their grid mesh.