The title question often appears during discussions of global surface temperatures. That is, GISS, Hadley Centre and NCDC only present their global land+ocean surface temperatures products as anomalies. The questions is: why don’t they produce the global surface temperature products in absolute form?

In this post, I’ve included the answers provided by the three suppliers. I’ll also discuss sea surface temperature data and a land surface air temperature reanalysis which are presented in absolute form. And I’ll include a chapter that has appeared in my books that shows why, when using monthly data, it’s easier to use anomalies.

Back to global temperature products:

GISS EXPLANATION

GISS on their webpage here states:

Anomalies and Absolute Temperatures

Our analysis concerns only temperature anomalies, not absolute temperature. Temperature anomalies are computed relative to the base period 1951-1980. The reason to work with anomalies, rather than absolute temperature is that absolute temperature varies markedly in short distances, while monthly or annual temperature anomalies are representative of a much larger region. Indeed, we have shown (Hansen and Lebedeff, 1987) that temperature anomalies are strongly correlated out to distances of the order of 1000 km. For a more detailed discussion, see The Elusive Absolute Surface Air Temperature.

UKMO-HADLEY CENTRE EXPLANATION

The UKMO-Hadley Centre answers that question…and why they use 1961-1990 as their base period for anomalies on their webpage here.

Why are the temperatures expressed as anomalies from 1961-90?

Stations on land are at different elevations, and different countries measure average monthly temperatures using different methods and formulae. To avoid biases that could result from these problems, monthly average temperatures are reduced to anomalies from the period with best coverage (1961-90). For stations to be used, an estimate of the base period average must be calculated. Because many stations do not have complete records for the 1961-90 period several methods have been developed to estimate 1961-90 averages from neighbouring records or using other sources of data (see more discussion on this and other points in Jones et al. 2012). Over the oceans, where observations are generally made from mobile platforms, it is impossible to assemble long series of actual temperatures for fixed points. However it is possible to interpolate historical data to create spatially complete reference climatologies (averages for 1961-90) so that individual observations can be compared with a local normal for the given day of the year (more discussion in Kennedy et al. 2011).

It is possible to develop an absolute temperature series for any area selected, using the absolute file, and then add this to a regional average in anomalies calculated from the gridded data. If for example a regional average is required, users should calculate a time series in anomalies, then average the absolute file for the same region then add the average derived to each of the values in the time series. Do NOT add the absolute values to every grid box in each monthly field and then calculate large-scale averages.

NCDC EXPLANATION

Also see the NCDC FAQ webpage here. They state:

Absolute estimates of global average surface temperature are difficult to compile for several reasons. Some regions have few temperature measurement stations (e.g., the Sahara Desert) and interpolation must be made over large, data-sparse regions. In mountainous areas, most observations come from the inhabited valleys, so the effect of elevation on a region’s average temperature must be considered as well. For example, a summer month over an area may be cooler than average, both at a mountain top and in a nearby valley, but the absolute temperatures will be quite different at the two locations. The use of anomalies in this case will show that temperatures for both locations were below average.

Using reference values computed on smaller [more local] scales over the same time period establishes a baseline from which anomalies are calculated. This effectively normalizes the data so they can be compared and combined to more accurately represent temperature patterns with respect to what is normal for different places within a region.

For these reasons, large-area summaries incorporate anomalies, not the temperature itself. Anomalies more accurately describe climate variability over larger areas than absolute temperatures do, and they give a frame of reference that allows more meaningful comparisons between locations and more accurate calculations of temperature trends.

SURFACE TEMPERATURE DATASETS AND A REANALYSIS THAT ARE AVAILABLE IN ABSOLUTE FORM

Most sea surface temperature datasets are available in absolute form. These include:

- the Reynolds OI.v2 SST data from NOAA

- the NOAA reconstruction ERSST

- the Hadley Centre reconstruction HADISST

- and the source data for the reconstructions ICOADS

The Hadley Centre’s HADSST3, which is used in the HADCRUT4 product, is only produced in absolute form, however. And I believe Kaplan SST was also only available in anomaly form.

With the exception of Kaplan SST, all of those datasets are available to download through the KNMI Climate Explorer Monthly Observations webpage. Scroll down to SST and select a dataset. For further information about the use of the KNMI Climate Explorer see the posts Very Basic Introduction To The KNMI Climate Explorer and Step-By-Step Instructions for Creating a Climate-Related Model-Data Comparison Graph.

GHCN-CAMS is a reanalysis of land surface air temperatures and it is presented in absolute form. It must be kept in mind, though, that a reanalysis is not “raw” data; it is the output of a climate model that uses data as inputs. GHCN-CAMS is also available through the KNMI Climate Explorer and identified as “1948-now: CPC GHCN/CAMS t2m analysis (land)”. I first presented it in the post Absolute Land Surface Temperature Reanalysis back in 2010.

WHY WE NORMALLY PRESENT ANOMALIES

The following is “Chapter 2.1 – The Use of Temperature and Precipitation Anomalies” from my book Climate Models Fail. There was a similar chapter in my book Who Turned on the Heat?

[Start of Chapter 2.1 – The Use of Temperature and Precipitation Anomalies]

With rare exceptions, the surface temperature, precipitation, and sea ice area data and model outputs in this book are presented as anomalies, not as absolutes. To see why anomalies are used, take a look at global surface temperature in absolute form. Figure 2-1 shows monthly global surface temperatures from January, 1950 to October, 2011. As you can see, there are wide seasonal swings in global surface temperatures every year.

The three producers of global surface temperature datasets are the NASA GISS (Goddard Institute for Space Studies), the NCDC (NOAA National Climatic Data Center), and the United Kingdom’s National Weather Service known as the UKMO (UK Met Office). Those global surface temperature products are only available in anomaly form. As a result, to create Figure 2-1, I needed to combine land and sea surface temperature datasets that are available in absolute form. I used GHCN+CAMS land surface air temperature data from NOAA and the HADISST Sea Surface Temperature data from the UK Met Office Hadley Centre. Land covers about 30% of the Earth’s surface, so the data in Figure 2-1 is a weighted average of land surface temperature data (30%) and sea surface temperature data (70%).

When looking at absolute surface temperatures (Figure 2-1), it’s really difficult to determine if there are changes in global surface temperatures from one year to the next; the annual cycle is so large that it limits one’s ability to see when there are changes. And note that the variations in the annual minimums do not always coincide with the variations in the maximums. You can see that the temperatures have warmed, but you can’t determine the changes from month to month or year to year.

Take the example of comparing the surface temperatures of the Northern and Southern Hemispheres using the satellite-era sea surface temperatures in Figure 2-2. The seasonal signals in the data from the two hemispheres oppose each other. When the Northern Hemisphere is warming as winter changes to summer, the Southern Hemisphere is cooling because it’s going from summer to winter at the same time. Those two datasets are 180 degrees out of phase.

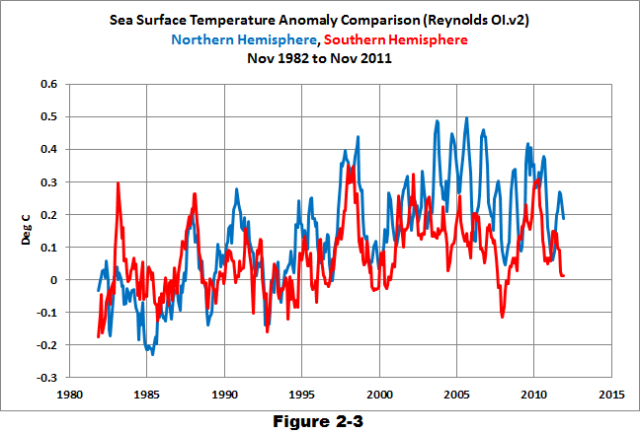

After converting that data to anomalies (Figure 2-3), the two datasets are easier to compare.

Returning to the global land-plus-sea surface temperature data, once you convert the same data to anomalies, as was done in Figure 2-4, you can see that there are significant changes in global surface temperatures that aren’t related to the annual seasonal cycle. The upward spikes every couple of years are caused by El Niño events. Most of the downward spikes are caused by La Niña events. (I discuss El Niño and La Niña events a number of times in this book. They are parts of a very interesting process that nature created.) Some of the drops in temperature are caused by the aerosols ejected from explosive volcanic eruptions. Those aerosols reduce the amount of sunlight that reaches the surface of the Earth, cooling it temporarily. Temperatures rebound over the next few years as volcanic aerosols dissipate.

HOW TO CALCULATE ANOMALIES

For those who are interested: To convert the absolute surface temperatures shown in Figure 2-1 into the anomalies presented in Figure 2-4, you must first choose a reference period. The reference period is often referred to as the “base years.” I use the base years of 1950 to 2010 for this example.

The process: First, determine average temperatures for each month during the reference period. That is, average all the surface temperatures for all the Januaries from 1950 to 2010. Do the same thing for all the Februaries, Marches, and so on, through the Decembers during the reference period; each month is averaged separately. Those are the reference temperatures. Second, determine the anomalies, which are calculated as the differences between the reference temperatures and the temperatures for a given month. That is, to determine the January, 1950 temperature anomaly, subtract the average January surface temperature from the January, 1950 value. Because the January, 1950 surface temperature was below the average temperature of the reference period, the anomaly has a negative value. If it had been higher than the reference-period average, the anomaly would have been positive. The process continues as February, 1950 is compared to the reference-period average temperature for Februaries. Then March, 1950 is compared to the reference-period average temperature for Marches, and so on, through the last month of the data, which in this example was October 2011. It’s easy to create a spreadsheet to do this, but, thankfully, data sources like the KNMI Climate Explorer website do all of those calculations for you, so you can save a few steps.

CHAPTER 2.1 SUMMARY

Anomalies are used instead of absolutes because anomalies remove most of the large seasonal cycles inherent in the temperature, precipitation, and sea ice area data and model outputs. Using anomalies makes it easier to see the monthly and annual variations and makes comparing data and model outputs on a single graph much easier.

[End of Chapter 2.1 from Climate Models Fail]

There are a good number of other introductory discussions in my ebooks, for those who are new to the topic of global warming and climate change. See the Tables of Contents included in the free previews to Climate Models Fail here and Who Turned on the Heat? here.

Oops… need a strike…

288.15 K (

15.15 Celsius) seems to be a good median for today’s mean.I say that with a huge grain of salt and should have added a LOL ROTFLMAO or maybe a sarc. Best I have come up with after digging about BESTs raw data, the world is even colder than you are led to believe, absolutely that is. 🙂

The important thing to take away from this is that temperature anomalies are not data, they are output of calculations based on a variety of assumptions. Absolute temperature measurements, on the other had, are data. Trying to detect changes in tenths of a degree globally, given the non-uniform coverage of the earth and various siting issues, is a rather fanciful endeavor. And trying to attribute causes is even more fanciful. And trying to prove any of it is probably impossible.

Richard Wright says:

January 30, 2014 at 2:35 pm

“The important thing to take away from this is that temperature anomalies are not data, they are output of calculations based on a variety of assumptions.”

Kinda. They have effect of bringing the differences between figures on a year to year basis into a range that we can display on a graph and not run off the top of the page.

If you use a 12 month rolling low pass filter of high quality you will end up with the same answer, just a slight vertical offset due to base periods chosen.

Try it and you will see the validity of that statement.

Richard Wright says:

January 30, 2014 at 2:35 pm

“The important thing to take away from this is that temperature anomalies are not data, they are output of calculations based on a variety of assumptions. Absolute temperature measurements, on the other had, are data.”

I fully agree. And I would like to elaborate my view on this.

Absolute temperature measurements are measurement result of independent variables.

It is very wise of a scientist to keep an undistorted record of the data set consisting of measurement results of independent variables. This is the data set a prudent scientist will revert to as basis when he later want to alter his model or the operations he performs on the data set. This is also the data set he will be wise to offer to others for their independent evaluation. If he do not offer his data set for independent evaluation other scientists will not have confidence in his results.

It is very unwise of a scientist to alter the data set consisting of measurements. The data set will loose integrity if such alterations are not fully documented.

Anomalies are the output from a set with operations performed on the data set. A prudent scientist will explain in detail which operations he performs on the input data set to provide the output data.

Richard Wright says:

January 30, 2014 at 2:35 pm

“Trying to detect changes in tenths of a degree globally, given the non-uniform coverage of the earth and various siting issues, is a rather fanciful endeavor. And trying to attribute causes is even more fanciful. And trying to prove any of it is probably impossible.»

If the hypothesis is correct, it should be possible to find a statistically significant correlation between independent (level of CO2 in ppmCO2) and dependent variables (average temperature K) For some averaging period.

Each temperature measurement will have its uncertainty. Let us say that each measurement has an uncertainty of 1 K.

The measurement uncertainty of an average of n measurements with uncorrelated measurement uncertainty will be equal to:

Uncertainty of the average = (Uncertainty of each measurement) / (Square root of number of measurements)

If you have 100 measurement points (which are not drifting) the measurement uncertainty will be equal to:

Measurement uncertainty of the average = 1 K / 10 = 0,1 K

It should be possible to find many more temperature measurement stations which has not drifted over the years due to external factors. In that way it should be possible to eliminate the measurement uncertainty as a significant contribution.

The time series of yearly average temperature will have a standard deviation which is larger than the measurement uncertainty of the average. This is due all other factors causing variation and the intrinsic variation of the measured quantity. The temperature record seems to indicate a variation which is significantly higher than it would be reasonable to attribute the measurement uncertainty of the average temperature.

The standard deviation of the time series for average temperature can be reduced by averaging over longer time or by increasing the number of measurement points. I am not sure what happens if you add measurement points by interpolation, but it can’t be good.

At some number of measurement points and and at some averaging time ( 1 year , 2 years, 5 years, 10 years, 20 years) it should be possible to demonstrate a positive and statistically significant correlation between measured average temperature (dependent variable) and level of CO2 (independent variable).

If not, it will be valid to say that a statistically significant correlation between CO2 and average temperature cannot be found. A scientist will have a very hard time claiming that a statistical significant correlation is present if he cannot find it with a statistic analysis designed to find correlation.

If the postulated dependency between average temperature and CO2 level cannot be shown to be a statistically significant correlation of a significant magnitude – what is it then supposed to be?

RichardLH says: January 31, 2014 at 1:21 am – About the statement from Richard Wright:

“The important thing to take away from this is that temperature anomalies are not data, they are output of calculations based on a variety of assumptions.”

RichardLH says:

“Kinda. They have effect of bringing the differences between figures on a year to year basis into a range that we can display on a graph and not run off the top of the page.”

I disagree with RichardLH. The statement from RichardLH does not seem to be a logically valid statement because:

Averaging of the measurements in the data set over a year will have the effect of producing output within a smaller range. This will be the case whether absolute temperatures or «anomalies» are used as quantity. The difference between highest and lowest value on temperature axis should be the same whether “anomalies” or absolute temperature are presented. Your statement seems to indicate that zero has to be shown on the temperature axis if thou use absolute values. That is not the case.

Further I disagree in your statement because it is not sufficiently precise. Several other operations, like interpolation and weighting, seems to performed on the input data set to produce the output anomalies. There are several other effects from these operations which might distort the integrity of the input data set and also the output. And if such operations are performed to alter the input data set, without keeping a record of the original input data set, the integrity of the original input data set will be lost.