The title question often appears during discussions of global surface temperatures. That is, GISS, Hadley Centre and NCDC only present their global land+ocean surface temperatures products as anomalies. The questions is: why don’t they produce the global surface temperature products in absolute form?

In this post, I’ve included the answers provided by the three suppliers. I’ll also discuss sea surface temperature data and a land surface air temperature reanalysis which are presented in absolute form. And I’ll include a chapter that has appeared in my books that shows why, when using monthly data, it’s easier to use anomalies.

Back to global temperature products:

GISS EXPLANATION

GISS on their webpage here states:

Anomalies and Absolute Temperatures

Our analysis concerns only temperature anomalies, not absolute temperature. Temperature anomalies are computed relative to the base period 1951-1980. The reason to work with anomalies, rather than absolute temperature is that absolute temperature varies markedly in short distances, while monthly or annual temperature anomalies are representative of a much larger region. Indeed, we have shown (Hansen and Lebedeff, 1987) that temperature anomalies are strongly correlated out to distances of the order of 1000 km. For a more detailed discussion, see The Elusive Absolute Surface Air Temperature.

UKMO-HADLEY CENTRE EXPLANATION

The UKMO-Hadley Centre answers that question…and why they use 1961-1990 as their base period for anomalies on their webpage here.

Why are the temperatures expressed as anomalies from 1961-90?

Stations on land are at different elevations, and different countries measure average monthly temperatures using different methods and formulae. To avoid biases that could result from these problems, monthly average temperatures are reduced to anomalies from the period with best coverage (1961-90). For stations to be used, an estimate of the base period average must be calculated. Because many stations do not have complete records for the 1961-90 period several methods have been developed to estimate 1961-90 averages from neighbouring records or using other sources of data (see more discussion on this and other points in Jones et al. 2012). Over the oceans, where observations are generally made from mobile platforms, it is impossible to assemble long series of actual temperatures for fixed points. However it is possible to interpolate historical data to create spatially complete reference climatologies (averages for 1961-90) so that individual observations can be compared with a local normal for the given day of the year (more discussion in Kennedy et al. 2011).

It is possible to develop an absolute temperature series for any area selected, using the absolute file, and then add this to a regional average in anomalies calculated from the gridded data. If for example a regional average is required, users should calculate a time series in anomalies, then average the absolute file for the same region then add the average derived to each of the values in the time series. Do NOT add the absolute values to every grid box in each monthly field and then calculate large-scale averages.

NCDC EXPLANATION

Also see the NCDC FAQ webpage here. They state:

Absolute estimates of global average surface temperature are difficult to compile for several reasons. Some regions have few temperature measurement stations (e.g., the Sahara Desert) and interpolation must be made over large, data-sparse regions. In mountainous areas, most observations come from the inhabited valleys, so the effect of elevation on a region’s average temperature must be considered as well. For example, a summer month over an area may be cooler than average, both at a mountain top and in a nearby valley, but the absolute temperatures will be quite different at the two locations. The use of anomalies in this case will show that temperatures for both locations were below average.

Using reference values computed on smaller [more local] scales over the same time period establishes a baseline from which anomalies are calculated. This effectively normalizes the data so they can be compared and combined to more accurately represent temperature patterns with respect to what is normal for different places within a region.

For these reasons, large-area summaries incorporate anomalies, not the temperature itself. Anomalies more accurately describe climate variability over larger areas than absolute temperatures do, and they give a frame of reference that allows more meaningful comparisons between locations and more accurate calculations of temperature trends.

SURFACE TEMPERATURE DATASETS AND A REANALYSIS THAT ARE AVAILABLE IN ABSOLUTE FORM

Most sea surface temperature datasets are available in absolute form. These include:

- the Reynolds OI.v2 SST data from NOAA

- the NOAA reconstruction ERSST

- the Hadley Centre reconstruction HADISST

- and the source data for the reconstructions ICOADS

The Hadley Centre’s HADSST3, which is used in the HADCRUT4 product, is only produced in absolute form, however. And I believe Kaplan SST was also only available in anomaly form.

With the exception of Kaplan SST, all of those datasets are available to download through the KNMI Climate Explorer Monthly Observations webpage. Scroll down to SST and select a dataset. For further information about the use of the KNMI Climate Explorer see the posts Very Basic Introduction To The KNMI Climate Explorer and Step-By-Step Instructions for Creating a Climate-Related Model-Data Comparison Graph.

GHCN-CAMS is a reanalysis of land surface air temperatures and it is presented in absolute form. It must be kept in mind, though, that a reanalysis is not “raw” data; it is the output of a climate model that uses data as inputs. GHCN-CAMS is also available through the KNMI Climate Explorer and identified as “1948-now: CPC GHCN/CAMS t2m analysis (land)”. I first presented it in the post Absolute Land Surface Temperature Reanalysis back in 2010.

WHY WE NORMALLY PRESENT ANOMALIES

The following is “Chapter 2.1 – The Use of Temperature and Precipitation Anomalies” from my book Climate Models Fail. There was a similar chapter in my book Who Turned on the Heat?

[Start of Chapter 2.1 – The Use of Temperature and Precipitation Anomalies]

With rare exceptions, the surface temperature, precipitation, and sea ice area data and model outputs in this book are presented as anomalies, not as absolutes. To see why anomalies are used, take a look at global surface temperature in absolute form. Figure 2-1 shows monthly global surface temperatures from January, 1950 to October, 2011. As you can see, there are wide seasonal swings in global surface temperatures every year.

The three producers of global surface temperature datasets are the NASA GISS (Goddard Institute for Space Studies), the NCDC (NOAA National Climatic Data Center), and the United Kingdom’s National Weather Service known as the UKMO (UK Met Office). Those global surface temperature products are only available in anomaly form. As a result, to create Figure 2-1, I needed to combine land and sea surface temperature datasets that are available in absolute form. I used GHCN+CAMS land surface air temperature data from NOAA and the HADISST Sea Surface Temperature data from the UK Met Office Hadley Centre. Land covers about 30% of the Earth’s surface, so the data in Figure 2-1 is a weighted average of land surface temperature data (30%) and sea surface temperature data (70%).

When looking at absolute surface temperatures (Figure 2-1), it’s really difficult to determine if there are changes in global surface temperatures from one year to the next; the annual cycle is so large that it limits one’s ability to see when there are changes. And note that the variations in the annual minimums do not always coincide with the variations in the maximums. You can see that the temperatures have warmed, but you can’t determine the changes from month to month or year to year.

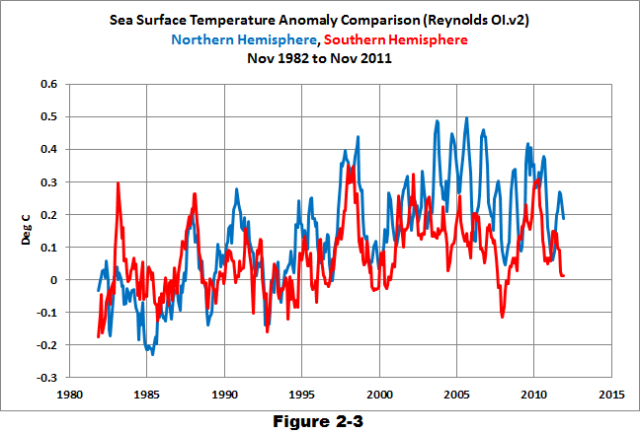

Take the example of comparing the surface temperatures of the Northern and Southern Hemispheres using the satellite-era sea surface temperatures in Figure 2-2. The seasonal signals in the data from the two hemispheres oppose each other. When the Northern Hemisphere is warming as winter changes to summer, the Southern Hemisphere is cooling because it’s going from summer to winter at the same time. Those two datasets are 180 degrees out of phase.

After converting that data to anomalies (Figure 2-3), the two datasets are easier to compare.

Returning to the global land-plus-sea surface temperature data, once you convert the same data to anomalies, as was done in Figure 2-4, you can see that there are significant changes in global surface temperatures that aren’t related to the annual seasonal cycle. The upward spikes every couple of years are caused by El Niño events. Most of the downward spikes are caused by La Niña events. (I discuss El Niño and La Niña events a number of times in this book. They are parts of a very interesting process that nature created.) Some of the drops in temperature are caused by the aerosols ejected from explosive volcanic eruptions. Those aerosols reduce the amount of sunlight that reaches the surface of the Earth, cooling it temporarily. Temperatures rebound over the next few years as volcanic aerosols dissipate.

HOW TO CALCULATE ANOMALIES

For those who are interested: To convert the absolute surface temperatures shown in Figure 2-1 into the anomalies presented in Figure 2-4, you must first choose a reference period. The reference period is often referred to as the “base years.” I use the base years of 1950 to 2010 for this example.

The process: First, determine average temperatures for each month during the reference period. That is, average all the surface temperatures for all the Januaries from 1950 to 2010. Do the same thing for all the Februaries, Marches, and so on, through the Decembers during the reference period; each month is averaged separately. Those are the reference temperatures. Second, determine the anomalies, which are calculated as the differences between the reference temperatures and the temperatures for a given month. That is, to determine the January, 1950 temperature anomaly, subtract the average January surface temperature from the January, 1950 value. Because the January, 1950 surface temperature was below the average temperature of the reference period, the anomaly has a negative value. If it had been higher than the reference-period average, the anomaly would have been positive. The process continues as February, 1950 is compared to the reference-period average temperature for Februaries. Then March, 1950 is compared to the reference-period average temperature for Marches, and so on, through the last month of the data, which in this example was October 2011. It’s easy to create a spreadsheet to do this, but, thankfully, data sources like the KNMI Climate Explorer website do all of those calculations for you, so you can save a few steps.

CHAPTER 2.1 SUMMARY

Anomalies are used instead of absolutes because anomalies remove most of the large seasonal cycles inherent in the temperature, precipitation, and sea ice area data and model outputs. Using anomalies makes it easier to see the monthly and annual variations and makes comparing data and model outputs on a single graph much easier.

[End of Chapter 2.1 from Climate Models Fail]

There are a good number of other introductory discussions in my ebooks, for those who are new to the topic of global warming and climate change. See the Tables of Contents included in the free previews to Climate Models Fail here and Who Turned on the Heat? here.

John Finn says:

January 26, 2014 at 1:43 pm

Isn’t it lucky we’ve got the UAH satellite record to provide such solid support for the surface temperature data.

##############################

huh?

You realize that UAH does not measure temperature. UAH ESTIMATES the temperature of the air miles above the surface. Its a very smooth grid. To estimate the temperature UAH has to use physics.

What Physics do they use?

The same physics that says that C02 will warm the planet. That is they run radiative transfer codes to estimate the temperature.

PSST.. there is no raw data in their processing chain. Its all been adjusted before they adjust it further.

PSST they only report anomalies…

I’ve followed these discussions for years now, but don’t recall seeing the data presented before quite like Figure 2.1. I get the point of evaluating the anomalies, but Fig. 2.1 really says a lot – and I wish the general public would see it. I wholeheartedly agree with Mark Stoval: Figure 2.1 shows how ridiculous it is to worry over 0.1 increases in the “global temperature average”. I had not realized the intra-year swings were quite so large. It certainly gives some perspective.

I’ve thought for a while now that it would be revealing to have an “instantaneous” world average temperature “clock” somewhere like Times Square showing the actual average in degrees C, with a few hundred well-sited world-wide stations reporting via radio/internet, analogous to the National Debt Clock. I can see why “Climate Science ™” wouldn’t want that.

Thanks, as always, Bob. By the way, I did buy your book – I’ve just been waiting to go on vacation to read it. (Didn’t get a vacation in 2013.)

When you take the seasonal changes out of the temperature record then you also take the signs of life interacting with the global climate out , it is easier to see the Earth just as a steam engine then. I would think that life has a greater impact on Earths climate than ocean cycles but life is seasonal.

Steven Mosher says:

“Bottom line. There was an LIA. Its

warmernot as warm now. and we did land on the moon.”There. Fixed, Steven.

Otherwise, we would not be regularly discovering new evidence of Viking settlements on Greenland, which appear as the land warms up and melts the permafrost that has been frozen since the LIA ended.

Emipirical evidence always trumps computer models.

Always.

If I put a two-quart pot of water on a cold stove, with temperature sensors spaced every cubic inch, I would expect some variation in temperature among the sensors, but could objectively determine an average temperature for the volume of water.

However, if I turn the heat on and come back in one hour, I would expect that every single sensor would record an increase in temperature – there would be no sensor that would record a decrease.

An increase in every temperature sensor — that would be proof of “global” warming.

Mr. Tisdale ==> This still doesn’t answer the question : “When all is said and done, when all the averaging and adding in and taking out is done, why isn’t the global Average, or US Average Land, or Monthly Average Sea Surface, or any of them simply given, at least to the public, in °C? If you are only giving ONE number, in an announcement to the general public, the year’s average global temperature — be it 17 or 0.2 — why not give it as 15.24°C rather than 0.43°C anomaly from some year period base?” You are always free to say, this is a shocking 0.2 degrees higher, lower than last year if you must.

Personally, I think the true PR reason is that it is hard to scare people with a number that would be something like 16°C or 61°F –> as in this quip….

Radio announcer speaking —— “People of Earth — Just think of the horror of it — if the average temperature of the Earth were to soar to the blistering temperature of 61° Fahrenheit.”

Steven Mosher says:

January 26, 2014 at 2:02 pm

John Finn says:

January 26, 2014 at 1:43 pm

Isn’t it lucky we’ve got the UAH satellite record to provide such solid support for the surface temperature data.

##############################

huh?

Steve

What is your point? I think you might have missed mine.

You appear to be confused between LIA and MWP. Easily done – they both have 3 alpha characters.

Oh? Can you back up your assertion with a link?

A good discussion of temperature anomalies and spatial correlation is in

http://preview.tinyurl.com/spatial-correlations [pdf]

Another assertion. Evidence?

Not sure why you’re belittling the cognitive competency of an inanimate object [the sun, not some poster . . .]

If your assertion is correct, extracting a tiny temperature anomaly on the order of 0.1C from a data set with an uncertainty of 1.6C requires significant model dependent assumptions.

markx,

That’s an informative comment. Thanks.

I have found an english language article that is contemporary to the Der Spiegel one, from the NY Times: Temperature For World Rises Sharply In the 1980’s

It’s quite interesting. Even then they were considering that the extra heat from global warming might be going into the oceans rather than be apparent in the surface data.

A puzzle:

From the 1988 NY Times article: “One of the scientists, Dr. James E. Hansen of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Institute for Space Studies in Manhattan, said he used the 30-year period 1950-1980, when the average global temperature was 59 degrees Fahrenheit, as a base to determine temperature variations. ”

From a current NOAA page on global temperature trends: “The average temperature in 2012 was about 58.3 degrees Fahrenheit (14.6 Celsius), which is 1.0 F (0.6 C) warmer than the mid-20th century baseline. ”

The baseline periods are ever so slightly different (1950 to 1980 versus 1951 to 1980) but that surely cannot explain a nearly two degrees Fahrenheit difference in the value calculated in 1988 and the value calculated in 2012.

Steven Mosher says:

January 26, 2014 at 2:02 pm

“What Physics do they use?

The same physics that says that C02 will warm the planet. That is they run radiative transfer codes to estimate the temperature. ”

Sleight of hand there. “The Physics” does not say “The Planet Will Warm”. If radiative transfer models would say that, why would we need GCM’s?

Mosher wants to create the same illusion as Gavin Schmidt (who frequently talks of “first principles” his modeling implements (in his mind only)); that negative feedbacks do not play a role and that radiative transfer models are sufficient for predictions of Global Warming.

They are of course not.

Steven Mosher says:

January 26, 2014 at 1:57 pm

“Bottom line. There was an LIA. Its warmer now. and we did land on the moon.”

Couldn’t resist implicating the Lewandowsky smear…

There are some some who suggest we should be using a kelvin scale because it shows how insignificant small temperature changes are. After all, if we took an average temperature of 15C (288K), a 2C (or kelvin) change is only about a 0.7% change in the absolute kelvin temperature of 288K. Surely not significant. Well, tell that to the fruit farmer who is wondering whether the low overnight will be 0C or dip down to -2C. One of two degrees is all the difference needed between getting rain or heavy snow. Or black ice forming on the highways. A 2C difference in the sensitive sections of the vertical temperature profile can easily determine whether severe thunderstorms (and possible tornadoes) will form or not. We use the centigrade scale (a subset of the kelvin scale) because it much better represents the general world we live in.

Another important reason behind the use of anomalies is the fact that it makes it easier to visually magnify the trend without it being obvious that that is what you are doing.

If you plot temps in absolute values without showing 0 degrees, most people will catch on that the trend is a lot smaller than it looks in the graph.

Baselines, baselines , baselines. When looking at “adjustments” made by various orginisations, it pays to calculate the amount the baseline moves.

Here is a graph I did when Warwick Hughes finally got the list of stations that Phil Jones used , I compared what the BOM numbers were to the Hadcrut 1999 numbers and the numbers that the UK met office released that were purported to be the “Based on the original temperature observations sourced from records held by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology”.

Just at this one station which represents ~ 15% of Australia’s land mass the baseline moves 0.83 C over the three sets of data.

http://members.westnet.com.au/rippersc/hccru2010.jpg

Warwick Hughes list of stations here.

http://www.warwickhughes.com/blog/?p=510

“Indeed, we have shown (Hansen and Lebedeff, 1987) that temperature anomalies are strongly correlated out to distances of the order of 1000 km.”

—————————————————————————–

Bob, are you telling us that James Hansen said using anomalies is a good thing to do so we’re doing it?

Some how that doesn’t sound right.

Tell that to a poor mountain rat and its family trying to evade overheating by migrating up the slope of a mountain only to find itself at the summit from where it has no place to go but extinct.

Desert rats will move in. Or temperate rats. Unless they have rabies. When in which case they become intemperate rats. We would prefer those go extinct.

You appear to be confused between LIA and MWP. Easily done – they both have 3 alpha characters.

If we analyze that modulo 26 we get (M-L) = 1 , (W-I) = 14 , and (P-A) = 15. Which says the key is ANO. That would be A No.

Uh. Crypto is a hobby of mine. Why do you ask?

Radio announcer speaking —— “People of Earth — Just think of the horror of it — if the average temperature of the Earth were to soar to the blistering temperature of 61° Fahrenheit.”

The global average temperature has currently deserted Northern Illinois. I miss it.

NOAA/NCDC continues to publish “The climate of 1997” as if it were the real deal, and we are entitled to treat it as such.

http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/climate/research/1997/climate97.html

Amongst other things, this document states categorically,

“For 1997, land and ocean temperatures averaged three quarters of a degree Fahrenheit (F) (0.42 degrees Celsius (C)) above normal. (Normal is defined by the mean temperature, 61.7 degrees F (16.5 degrees C), for the 30 years 1961-90).”

Therefore, the average global surface temperature in 1997 is 16.92°C, and 16.5°C the average global surface temperature between 1961 and 1990. The WMO states equally categorically,

“The warmest year ever recorded was 2010, with a mean temperature anomaly estimated at 0.54°C above the 14°C base line.”

http://library.wmo.int/pmb_ged/wmo_1119_en.pdf

The 14°C base line in this case is the 1961 to 1990 average global surface temperature. Therefore, according to the WMO, the “warmest year ever recorded” has a temperature of 14.54°C, which is 2.38°C less than the average global surface temperature in 1997, as reported by NCDC. Moreover, on the basis of NOAA’s “The climate of 1997”, every year from 1900 to 1997 has a global surface temperature between 16°C and 16.92°C, which entails, that every year from 1900 to 1997 is “hotter” than the WMO’s “hottest” year on record.

The reason why NASA, NCDC, etc, prefer to work with temperature anomalies rather than absolute temperatures is to disguise the unpalatable truth, that once absolute (or actual) temperatures are brought into the equation, it becomes painfully obvious, that estimates of global surface temperatures come with a margin of error so large, that it becomes impossible to say for certain by how much global surface temperatures have changed since 1850. Thus, HadCrut4 uses the interval from 1961 to 1990 for the purpose of computing global surface temperature anomalies from 1850 to the present. If X°C is the annual global surface temperature anomaly for any year Y within HadCrut4’s scope, the actual temperature for Y could be as high (16.5+X)°C, per NCDC, or as low (14+X)°C, per the WMO.

[(16.5+X)+(14+X)]/2 = 15.25+X

[(16.5+X)-(14+X)]/2 = 1.25

That is to say, the actual GST of Y is 15.25+X, with an uncertainty of (+/-(1.25))°C, and an uncertainty of that amount is more than sufficient to swallow whole all of the global warming which is supposed to have taken place during the instrumental temperature record. So, Bob, I have this question for you, “What value do any estimates of global surface temperatures have, either as anomalies or actuals, when they come with a caveat of (+/-(not less than 1.25))°C?”

from Maxld

“””””….. We use the centigrade scale (a subset of the kelvin scale) because it much better represents the general world we live in……”””””

Well actually it is the Celsius scale that is related to kelvins; perhaps a subset if you like.

It puts zero degrees C at 273.15 kelvins, and 100 degrees C at 373.15 kelvins.

But the Celsius scale IS a “centigrade” scale, in that it divides its range linearly into 100 equal parts.

My rule; “Use deg. C for incremental temperatures, and use kelvins for absolute Temperatures.”

And the general world we live in, seems to cover a range from 180 K up to around 330 K ,so I don’t see any advantage in saying -93 to + 60 deg. C

What is average temperature of about 70% of earth surface area of world’s ocean.

And what is the average temperature of about 30% of earth surface area which is land.

And if don’t know, what do guess the average ocean and land temperature would be?

The simplest explanation for your question is that certain powers that have been wanted premature decisions taken on matters involving trillions of dollars of investment/non-investment prior to appropriate internally consistent, globally standard data sets of 100 years around the globe being available.

The simple answer should be: hold back on doing global data analysis until the global data set is present, consistent and reliable.

The merchants of doom say ‘we don’t have the time for that’.

I say: ‘with 17 years of pause, we have more than enough time for that’.

Climatologists are doing the equivalent of telling a 9 year old child what their career choices must be, before they’ve even got to the stage of knowing what they might in fact be.

Bill Illis says:

January 26, 2014 at 5:11 am

Global Temperature average in Kelvin.

Hadcrut4 on a monthly basis back to 1850.

Beautiful graphs, now warmists , take one look at those graphs and try to tell me that feedback is not nett negative.

Nick Boyce says: January 26, 2014 at 10:09 pm

NOAA/NCDC continues to publish “The climate of 1997″ …. http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/climate/research/1997/climate97.html ….. this document states categorically,

“For 1997, land and ocean temperatures averaged three quarters of a degree Fahrenheit (F) (0.42 degrees Celsius (C)) above normal. (Normal is defined by the mean temperature, 61.7 degrees F (16.5 degrees C), for the 30 years 1961-90).”

Can someone (Steve Mosher perhaps?) please explain what has changed in the last decades that has apparently resulted in some recent revision downwards of these earlier “global mean temperatures”?

In 1997 we are told that we are comparing with a past 30 year mean temperature of 16.5°C. (the 30 years 1961-90).

Now we are told that same temperature period really averaged 14.0°C.

What has changed? Did more data come in? Is it still coming in? Did TOD adjustments mean it all needed revising downwards by 2.5°C?

And this is not a ‘one-up’ publication – in every period since 1988, reference was to earlier periods which are warmer that we are now quoted. http://wattsupwiththat.com/2014/01/26/why-arent-global-surface-temperature-data-produced-in-absolute-form/#comment-1550024

I would love to hear the explanation.