David Archibald

Vitamin C and Climate

One of the predecessor animals of humans lost the ability to make vitamin C in the Eocene, 40 to 60 million years ago. The world was a lot warmer then and most land areas were covered with rain forest. There was plenty of vitamin C available all year round in the fruit of the flowering plants that had evolved not long before.

There were two evolutionary advantages for losing the ability to make vitamin C. Firstly, producing that vitamin C at the rate of 20 mg/kilo of body weight/day would have taken 0.1% of resting body energy, which is a significant advantage over time. Secondly, the antioxidant effect from the vitamin C produced by the liver is exactly offset by the oxidising effect of the hydrogen peroxide also produced in the liver in the making of the vitamin C.

While that vitamin C travels all over the body, the hydrogen peroxide has to be reduced by other antioxidants made in the liver. Because the liver is only two percent of human body weight, this is a big load on the liver and would have resulted in higher rates of liver disease and failure. In animals that do make their own vitamin C, the production of antioxidant molecules by their reducing effect is roughly one third vitamin C, one third glutathione, and one third uric acid. All glutathione production by the liver would have to go to offsetting the hydrogen peroxide resulting from making vitamin C. Not having to have the liver work so hard would have been a big driver for the mutation to lose the ability to make vitamin C.

So far, so good. Then Antarctica drifted over the South Pole, the Antarctic ice sheet appeared, and the current ice age began. The world became colder and drier. There was no longer a year-round supply of vitamin C from fruit. The human range expanded to all the climatic zones. Most of humanity now lives with a chronic vitamin C deficiency (though in places like Malaysia, there is a high rate of diabetes because people eat too much fruit).

We know how much vitamin C we need because of what other animals do. For mammals, that is shown in this graph:

Figure 1: Daily Vitamin C production in mg per kilo of body weight

In carnivores and omnivores, vitamin C production is typically near 20 mg/kg of body weight/day. Dogs have a high level because of their high metabolic rate. As omnivores, humans need about 20 mg/kg of body weight/day. For a normal person of 70 kg, that equates to 1.4 grams — equivalent to three 500 mg tablets, assuming it all gets through to the bloodstream.

Ruminants need a lot of vitamin C to cope with all the oxidative stress from fermentation. Among the ruminants, vitamin C production is proportional to how bad the country the species can survive on. So, goats produce more than twice as much as cows and seven times as much as pigs. The non-ruminant herbivores have a normal sort of production rate. Other phyla also produce vitamin C. In the fishes, bony fish produce vitamin C. Fruit flies make their own vitamin C, but crabs don’t.

The recommended daily allowance for vitamin C in Australia is 45 mg per day and we consume 110 mg per day on average. That is still less than 10% of what other omnivores use. Most of us are living our lives chronically vitamin C deficient. There is another effect we are missing out on due to our nonfunctional L-gulonolactone oxidase gene, the one that makes vitamin C. Production of vitamin C in animals reacts to stress. Infection can cause vitamin C production to increase two to five-fold, trauma can increase it three to six-fold, prolonged exertion can increase it two to four-fold, the increase due to heat stress can be up to three-fold, and crowding can increase it two-fold. So an infected 50 kg goat can produce up to 50 grams of vitamin C per day. Humans don’t get the benefit of this disease response. Our little shrew-sized ancestors back in the Eocene made a devil’s bargain on vitamin C, not expecting the climate to get colder.

This explains the effect seen in a 2020 study of the positive response of covid patients to N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) dosing. NAC is a strong anti-oxidant. Because humans live their lives chronically vitamin C-deficient, any anti-oxidant can fill the gap and produce a positive result. The US Federal Drug Administration attempted to ban NAC because they didn’t want anything to compete with the covid vaccines that were then coming.

Figure 2: Maximum daily Vitamin C production increase in response to stress

For each species, the left hand bar shows the normal daily vitamin C production rate. The right hand bar shows the maximum measured production rate when the animal is stressed.

Most mammals have the ability to significantly increase vitamin C production in response to stressors such as trauma and disease. Given what happens in animals, it is advisable for humans to increase vitamin C consumption in response to disease. For a 70 kg person, a five-fold increase from the normal level of omnivores would be seven grams per day.

We have made some adaptations to being chronically vitamin C deficient. Humans and other great apes have lost the uricase enzyme that degrades uric acid. Uric acid is a powerful extracellular antioxidant. At the high end of their concentration ranges, humans have seven times the concentration of uric acid in plasma as pigs do. This offsets about 40% of the effect of the loss of vitamin C in humans. But the effect is only in serum and uric acid does not support collagen synthesis or immune cell function. Taking up to 500 mg per day of vitamin C lowers the serum uric acid level by up to 20%.

Another human adaptation to low vitamin C levels is to concentrate it in white blood cells at 20 to 80 times the level in plasma. The brain also retains vitamin C, including during deficiency. Humans have evolved to waste almost no vitamin C, though this only works if there is an intake in the first place. In effect, humans rely heavily on secondary antioxidant systems because the primary system is missing.

All that is to provide background to the disease implications. Vitamin C is required, as in not optional, for collagen cross-linking in skin, blood vessels and joints, mitochondrial protection, immune surveillance, stem cell maintenance and suppressing cancers. Vitamin C has a big role in slowing aging by better connective tissue integrity, lower frailty and slower immune senescence. Aging in humans resembles chronic low-grade vitamin C deficiency.

Humans show rapid depletion of plasma vitamin C during infections with the concentration often falling into the scurvy range. This in turn causes capillary leaks and oxidative damage. The human vitamin C level in plasma is normally in the range of 40 to 60 µmoles per litre. During infection this falls to under 20 µmoles per litre. Scurvy starts at below 11 µmoles per litre. Relative to other animals, the human vitamin C level collapses rapidly under stress. In contrast, animals go from the 60 µmoles per litre baseline to up to 100 µmoles per litre under stress. That said, absorption of vitamin C drops sharply from oral dosing above three to five grams per day. Five grams per day will get you to about 90 µmoles per litre. There is no increase in plasma vitamin C level beyond 10 grams orally per day. Taking vitamin C intravenously bypasses the limits imposed by oral dosing. Taking one to five grams intravenously approximates what animals achieve during severe stress.

One of the things that vitamin C does during infection is to protect mitochondria from oxidation. Many hypoxic disease states are vitamin C-sensitive, not oxygen-related per se. Animals that make their own vitamin C maintain mitochondrial output during infection or exertion. Humans fatigue faster and accumulate inflammatory byproducts.

With respect to viral infection, vitamin C enhances type 1 interferon production. This slows viral load early, before viral load peaks. N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), another strong antioxidant, likely works in the same way. Vitamin C also keeps iron bound to proteins with the result that less is available for viral proteins. It also limits viral oxidative signalling cascades, capping the replication rate. In summary, viruses replicate fastest in vitamin-C depleted cells. Animals respond to viral infections by increasing vitamin C synthesis; humans experience uncontrolled inflammatory amplification instead.

Vitamin C, vitamin D, and zinc have complementary roles in controlling viral infections. Vitamin C acts within hours while vitamin D acts over days to weeks. Vitamin D controls gene transcription in making proteins, prevents immune overshoot, and reduces autoimmunity and inflammatory overshoot. Zinc is needed for making antiviral enzymes, inhibition of RNA replication, and increasing the function of the thymus. Zinc is quickly depleted during infection. Zinc works best when vitamin C keeps the oxidative state of cells stable. This is a simpler way of putting it:

- Vitamin C responds quickly to a viral infection.

- Zinc slows viral replication.

- Vitamin D prevents the immune system from burning the house down.

- Mammals evolved to make more vitamin C while infected because timing matters.

- Humans lost the buffer of being able to increase vitamin C production in response to the stress load and pay for it under viral stress.

The normal blood concentration of vitamin C is 12 µg/ml. Cells of the immune system concentrate vitamin C within them at 20 to 80 times higher than the plasma level. So vitamin C is important in a properly functioning immune system. Immune system impairment starts when the plasma vitamin C level falls below 8 µg/ml. Immune cells work by creating reactive-oxygen-species to kill pathogen cells. The role of vitamin C is to protect the immune cells during this oxidative burst.

With respect to cancer, a high proportion of chemotherapy drugs work by creating reactive-oxygen-species (ROS) in the mitochondria. This stresses the cancer cell so it sends signals to the cell surface to make more death receptors on the cell surface. Most antioxidants negate this effect to some extent. With vitamin C at high blood concentrations, which can only be achieved by intravenous injection, this inverts to create an anti-cancer effect. Cancers have a voracious appetite for glucose. Oxidised vitamin C looks similar to glucose to the transporter proteins that take glucose into cells. Once in the cancer cells, this overload of oxidised vitamin C creates ROS which damages it. As a cancer treatment, intravenous vitamin C is most effective in the types that have a low ability to break hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen

The first dose in intravenous vitamin C treatment of cancer is usually 15 grams. This is to make sure that the body is not overloaded with necrotic cancer cells if too many of them die at the beginning of treatment. The next dose is 30 grams. Daily dose rates of up to 90 grams have been used. This is equivalent to what two 50 kg, infected goats might produce between them.

David Archibald is the author of The Anticancer Garden in Australia.

An evolutionary trade-off…

Super interesting article! Thanks for posting this. I’m going to go right now and buy a bunch of oranges and some vitamin C supplements!

Topic is way, way outside my expertise, but I did notice one thing that is clearly incorrect. It is not true that, “The US Federal Drug Administration attempted to ban NAC because they didn’t want anything to compete with the covid vaccines that were then coming.”

There’s no evidence that anyone in the FDA ever sought to ban anything to prevent competition with Covid vaccines. Anti-vax scammers make up baseless accusations like that, and I’m surprised that a very smart guy like David Archibald was fooled by them.

Apparently the evidence is mixed regarding usefulness of NAC in Covid patients. I asked ChatGPT for references to studies about it; in case you want to investigate further, here’s the list it provided:

Shi & Puyo — Evidence review of NAC in COVID-19

Shi, Z. & Puyo, C. A., N-Acetylcysteine to Combat COVID-19: An Evidence Review. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management (2020). https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S273700 BMJ

Liu et al. — Systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs of NAC in COVID-19

T-H. Liu et al., Clinical efficacy of N-acetylcysteine for COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Heliyon (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25179 PMC

Atefi et al. — RCT of oral NAC in COVID-19 patients

N. Atefi et al., Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of oral N-acetylcysteine in patients with COVID-19. Immunity, Inflammation and Disease (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/iid3.1083 c19early: COVID-19 treatment analysis

de Alencar et al. — Double-blind RCT (severe COVID-19)

de Alencar et al., Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial with N-acetylcysteine for treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by COVID-19. Clinical Infectious Diseases (2020). https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1443 University of Washington

Gamarra-Morales et al. — NAC IV in critically ill COVID-19 (Nutrients 2023)

Gamarra-Morales Y. et al., Response to Intravenous N-Acetylcysteine Supplementation in Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19. Nutrients 15(9):2235 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15092235 MDPI

There’s no evidence that anyone in the FDA ever sought to ban anything

In July 2020, FDA took unprecedented action to prohibit sales of NAC as a dietary supplement, which has safely been on the market for over 25 years –

https://www.crnusa.org/congress-tell-fda-stop-limiting-consumer-access-safe-beneficial-dietary-supplements

“CRN contacted FDA over six months ago to reverse its legally indefensible position and, after no meaningful response, filed a Citizen Petition on June 1, 2021. ”

Dr Faust has nothing on Dr Fauci.

Googled to check:

“The FDA has determined that N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) is technically excluded from the dietary supplement definition because it was approved as a drug (acetylcysteine) before being marketed as a supplement, raising legal concerns about its sale. However, the FDA has not banned it; instead, they’ve announced they are exercising “enforcement discretion,” meaning they won’t actively stop sales of existing NAC supplements while considering new rules to allow it as a supplement, a decision supported by industry pushes. So, while a legal gray area exists, NAC supplements remain widely available.”

Picking a sidein the argument starts to require conspiracy theories.

strat, I would really appreciate it if you wouldn’t edit what I write to change my meaning.

This is what I wrote:

That’s a true statement.

This is your edited version:

That’s a false statement.

Go ahead and criticize what I write, that’s fine. But don’t change it from something true to something false and then dispute what I didn’t actually write.

[as much as I agree with the ideas and sentiment in this comment, the language is over the top~mod]

They did with NAC as they did with Hydroxychloroquine as they did with Ivermectin as they tried with Vitamine D etc etc

HCQ and IVM are prescription drugs. So, no, the FDA didn’t do with NAC what they did with HCQ and IVM.

Vitamin D is OTC, and has never been restricted in any way. So, no, the FDA didn’t do with NAC what they did with Vitamin D.

None of those prevent or cure Covid-19, BTW. None of them “compete” with Covid-19 vaccines, either.

There’s no evidence that anyone in the FDA ever sought to ban anything to prevent competition with Covid vaccines.

IVM wasn’t an prescription drug f.e. in India. You could order it for delivery f.e. to the US.

But you didn’t get it, because the US customs services catched parcels with IVM from India.

Vit. D wasn’t “banned”, correct so far, but if you searched for vit.D via google or others, about 90% of results were warnings to use vit D.(overdosis)

First HCQ had proven success in France (Marseille, Raoult),

later in India. India later changed to IVM because of possible sideeffects of HCQ and better results.

https://covid19.onedaymd.com/2021/10/did-ivermectin-work-in-india-how-did.html

NAC

https://www.medicinenet.com/why_is_nac_being_discontinued/article.htm

Your side started spreading scary stories about too much VitD causing heart failure.

Scaring the masses via mass media is too, a form of censorship. Censoring individual thought (and accomplishment) is what your masters do. Sorry, owners, not masters, owners, bots are owned…

The rest of your diatribe may or may not be pertinent and valid, but to claim the FDA never tried banning anything is either too clever by half, a strawman, or just plain lies. The government certainly tried banning and censoring too often to feign ignorance, and trying to pretend the FDA was not involved doesn’t pass the smell test. Strativarius has links, but they should be unnecessary. The censorship and canceling and banning was too in-yer-face for anyone to have missed.

Scarecrow wrote:

The lie is the accusation that I said such a ridiculous thing. That was just strat’s misquote of me.

This is what I actually wrote:

That’s a true statement.

This is strat’s edited version:

That’s a false statement.

Anti-vax scammers? That’s a funny one. The Covid jab was the scam. The FDA allowed a poorly conceived experimental injection to be forced on tens of millions, with no accountability for the manufacturers and or the officials who essentially used the entire population in a vast medical and socio-political experiment with no informed consent, while simultaneously restricting and vilifying other treatment modalities. The “vaccine” was neither safe nor particularly effective, did not prevent the spread of the virus despite claims to the contrary, and enriched the manufacturers in what can only be called a government-sponsored conspiracy.

It was clear within a few months, well before the injections became available, who was at risk from the virus. I chose to remain in the control group even though I was 60 years old. I also maintained a steady regimen of vitamin supplementation, including moderately high doses of D and C, and minerals, including zinc. I contracted the SARS-CoV-2 infection in various strains at least twice. It was a mild to moderately severe cold, unless one was afflicted with other serious pre-existing conditions.

A century of epidemiology and sound medical practice was discarded and replaced by a fear campaign that undermined public trust and divided people into poorly informed camps, and the scars remain as stark today as they were then.

Amen! The preliminary data from Italy showed the average age at death with COVID was so close to the average age at death, period, that distinguishing the two was within the error range. That cruise ship with mostly old passengers was locked up for a week or two and only had three deaths, sez my memory. It was obvious right from the start that COVID was not going to repeat the 1918 flu, and I found out I had lived through two pandemics which killed more people (late 1950s, and a decade or two later, without knowing about either and without the general fear the government generated.

The COVID pandemic was a softy, and 99% of the problems from it were due to government overreaction.

Scarecrow, the 1918 flu pandemic is estimated to have killed 2% of the world population.

The Covid-19 pandemic is estimated to have killed 0.1% of the world population.

Without the vaccines it would have killed more, but probably no more than twice that.

So it’s true that the 1918 flu pandemic was much worse. But Covid-19 still killed at least 7 million people, including 1.22 million Americans.

That’s not a “softy,” that’s a catastrophe, except in comparison to a worse catastrophe.

Most of those American deaths could have been prevented if our leadership had been as competent as, say, the South Koreans. But the deaths weren’t caused by “government overreaction.”

For perspective, this country has twice gone to war over attacks which killed under 3000 Americans.

There’s no way to know how bad the next pandemic will be. Pray it’s not as bad as the 1918 flu.

I was in one of the vaccine trials, but it turned out that I was in the placebo arm, so when I qualified I got the Moderna vaccine. Since then I’ve kept up with the boosters. To the best of my knowledge I haven’t had Covid-19.

However, I lost people to Covid-19 who were dear to me. (Most people did; didn’t you?)

Yes, they were old. But they were still dear to me.

Quote: “But Covid-19 still killed at least 7 million people, including 1.22 million Americans.”

That’s quite a statement considering:

My diagnosis: group hysteria has caused you and others to THINK people died from Covid-19

What an impressive list of errors!

1. Yes, Virginia, SARS-CoV-2 is real.

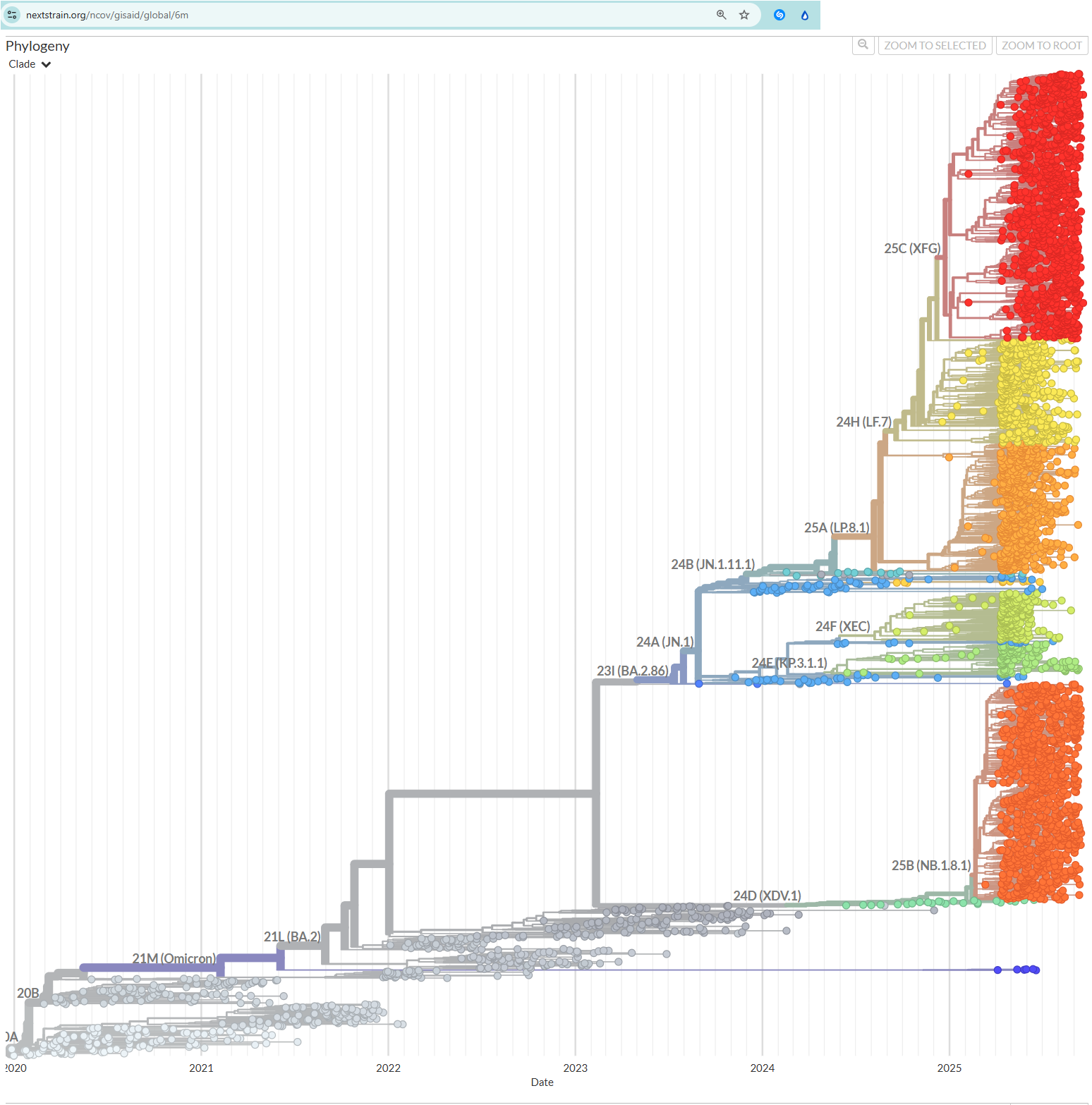

In fact, it has been genetically sequenced, many many times. Here’s a genetic “family tree.”

https://nextstrain.org/ncov/gisaid/global/6m

2. It seems you do not understand the limitations of Koch’s postulates. Here’s a paper which should help:

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8544537/

3. PCR tests can give false negative or occasionally false positive results, but they are still very useful:

https://www.cochrane.org/evidence/CD013705_how-accurate-are-rapid-antigen-tests-diagnosing-covid-19

4. “The definition of pandemic” was not changed.

5. “The definition of vaccin[e]” has changed over the years, but not in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. It used to mean “related to cows.”

Now the definition is more expansive. So what?

6. Many diseases have similar symptoms. So what?

7. Covid-19 killed over 1.2 million Americans. Typical seasonal flu “only” kills 20,000 to 60,000 Americans per year. That is a very significant difference in lethality.

Thanks to vaccination and improved treatment (Paxlovid!), the lethality of Covid is now much lower than it was in 2020.

8. Those 1.2 million confirmed Americans killed by Covid-19 are from causes of death as determined by coroners, medical examiners, and other doctors. They aren’t infallible, but they’re usually right. Claims that that 1.2 million is an large overcount are wrong.

There is zero evidence that the Covid jab saved any lives at all. The epidemiological trials were tainted, of too brief a duration, had limited exposure data, and had no valid control group.

Deaths in America are likewise without adequate documentation or controls to make any claims other than they were far fewer than the hype had insisted, minimal or virtually non-existent in any but the most health-compromised groups, and certainly exacerbated by heavy-handed government policy. All deaths were tragic, and made more so by said policies, as was the damage done to millions of others in fiscal and social costs from draconian overreach.

The harm from unnecessary injections is very real, documented, and increasingly being revealed.

That’s completely wrong, Mark.

The data is in: vaccination against Covid-19 was a spectacular success. The Covid vaccines saved millions of lives, including hundreds of thousands of Americans. The accelerated development of those vaccines was one of the two greatest successes of the first Trump Administration.

Studies consistently show that vaccination against Covid-19 improves health outcomes. Vaccination REDUCES risk of Covid-19 disease, REDUCES disease transmission, REDUCES risk of severe illness or death, and REDUCES age-adjusted all-cause mortality.

Here’s a 2024 Norwegian study:

https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.12.15.24319058

Here’s an article about it:

https://www.techarp.com/science/covid-vaccines-lower-mortality-norway-study/

Here’s an earlier study:

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7043e2.htm

Here’s another:

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa2119451

The fact that many people have health problems after getting vaccinated does not mean vaccination caused those problems, any more than the existence of hurricanes means that we’re being harmed by “climate change.” There would only be evidence of causation if the incidence or severity was GREATER than expected.

About 24 hours after my second Moderna jab, I got a very sore foot. It hurt a lot, and it swelled up so badly that it was difficult to get my shoe on.

Do you think that was due to the vaccine?

I don’t think the vaccine caused it. I think it was caused by the nail that I stepped on.

Bad things happen to people’s health in this broken world. Sometimes the cause is obvious, as was the case for my foot. But very often the cause is not obvious. If I’d had a heart attack, instead of a nail through my foot, would you have blamed the jab?

The way scientists evaluate efficacy vs risk for vaccinations (and other medications) is by statistics. The statistics conclusively show that vaccination improves health outcomes.

Studies consistently show that vaccination against Covid-19 improves health outcomes. Vaccination REDUCES risk of Covid-19 disease, REDUCES disease transmission, REDUCES risk of severe illness or death, and REDUCES age-adjusted all-cause mortality.

Nothing correct in your statement, sorry.

By the way, you are not up-to-date about the number of side effects, deaths, upcoming deaths ( heart failours, cancer) and that reducing transmission never was researched in any way and didn’t happen. (confirmed in an official hearing of the German Gouvernement by a official leading spokesperson from Pfizer).

The nasal system has an immune system at it’s own, and the mRNA “vaccine” hasn’t any influence to it. And the transmissions source is the nasal system.

That is very weak evidence at best, and does nothing to prove the jab saved any lives. Statistics do not prove anything other than relationship by correlation, and these are very inconclusive ones. The treatments may have had some effect, but the jab was entirely unnecessary for the vast majority of those forced or coerced into submitting to it.

As for your “foot”note strawman argument, that is even more pathetic than the weak attempt to insist the jab saved millions of imaginary lives. No other vaccine has racked up more complaints on the Vaccine Adverse Effects Reporting System (VAERS), and the full extent of the damage is only now being exposed despite attempts to cover it up.

Your silly story does remind me of the story of the guy who was killed in a motorcycle accident but was claimed to have died from Covid. It is very clear that most of the deaths attributed to the virus were, in fact, deaths from other causes and preexisting conditions, some of which were certainly exacerbated by the infections.

Perverse monetary incentives inspired some very creative death certificate entries. We can never know who or how many died as a direct result of the virus, or even if attributed deaths were from SARS-2 CoV, some other virus, such as H1N1, or simply coincidental, since the testing regimens used were entirely unsuited for the purpose.

The entire “pandemic” was an overblown drama, and while the virus existed and did pose a threat for a small proportion of the population, it was nowhere near the crisis it was scripted to be.

“I asked ChatGPT for references to studies about it; in case you want to investigate further, here’s the list it provided:”

And you accept its results as kosher ?? How sweetly naive.

In my use of AI I’ve found it to be – Fast, Inaccurate, Unintelligent & easily confused, sometimes giving opposing answers from the same data.

Appears to have preconceived ideas programmed in.

Try asking a question you know the answer to; like …

“who demonstrated the first incandescent light bulb (filament in a glass envelope)”

[The answer should be Lindsay 1835 ]

You get Thomas Edison in 1879.

However, that was Henry Woodward and Matthew Evans’ 1874 patent bulb, which Edison acquired in 1879, a year after Joseph Swan obtained his patent.

After a lot of vasilation from GPT, we finally get this admission …

“My earlier statement about Thomas Edison having the first successful demonstration was inaccurate in the context of early bulb development. James Bowman Lindsay indeed demonstrated an incandescent light bulb with a filament in a glass envelope earlier in 1835.

Summary of Key Points:

Thank you for catching that mistake, and I appreciate your understanding as we clarify this important historical detail! ”

Will it have learned this time, or revert back to the original default of Edison again??

Just ran the same question & got ‘Edison’ again !!

So if you push hard enough, it will eventually find the correct answer & admit error, but won’t learn, it just reverts back to the original default.

AI = GIGO, use with caution, just use as a fast librarian for getting books from shelves, but you need to tell it which books & then you need to read them.

AI tools are useful, but you have to treat ’em like President Reagan treated the Russians:

Доверяй, но проверяй (“Doveryay, no proveryay” which means “Trust, but verify.”)

https://www.c-span.org/clip/5158643

The scam was calling MRNA drugs vaccines. They are not by any traditional definition.

mRNA vaccines are certainly vaccines. The fact that they’re a relatively new vaccine technology doesn’t mean they aren’t vaccines.

The definition has evolved over the years, due to changing technology, but it’s not some conspiracy to deceive people. Here are the “traditional” vax definitions, from my grandfather’s 1905 American Dictionary of the English Language:

VACCINATE, 𝘷.𝘵., to inoculate with the cowpox as a preventive against smallpox.

VACCINE, 𝘢𝘥𝘫., pertaining to or derived from cows.

The Manufacturers such as Modenna refer to them as gene therapy. In The Netherlands regulations were changed to allow these concoctions to be adminstered and they were specifically reference as gene therapy.

So who would I believe to decide wether this is experimental gene therapy or a vaccin like the vaccins we have known for over 200 years?

It’s Dave Burton or Moderna and the Dutch government….

Though one..

huls wrote, “The Manufacturers such as Modenna refer to them as gene therapy.”

That’s not true. Nobody calls the Covid-19 vaccines “gene therapy” except lying antivax scammers.

If you believe that mRNA vaccines are gene therapy then you don’t know what gene therapies are. Here’s where you can learn:

• https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/what-gene-therapy

• https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/therapy/procedures

mRNA vaccines are not even very similar to gene therapy. Not everything that involves genetic material is “gene therapy.”

Gene therapies deliver human genetic material, typically by the use of viral vectors, to cell nuclei..

mRNA Covid-19 vaccines are very different. They don’t use viral vectors (though some other vaccines do use viral vectors), and they don’t deliver human genes. Instead, they contain virus-like genetic material.

Viruses inject viral genetic material into cells, programming the cells to create copies of the viruses. That changes the genetic material in the cells which they infect, but it doesn’t make viruses “gene therapy.” That’s just how viruses work.

In fact, traditional live-virus vaccines are more like gene therapies than are mRNA vaccines, because both traditional live-virus vaccines and viral vector gene therapies contain viruses. mRNA vaccines do not contain viruses.

Yo Dave, listen when grown ups speak.

Moderna’s November 2018 Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) registration statement also confirms that its mRNA injections are defined as gene therapy, clearly stating that “mRNA is considered a gene therapy product by the FDA.”

The September 2019 SEC filing for BioNTech (its mRNA technology is used in the Pfizer vaccine) is equally clear, stating on page 21:

“In the United States, and in the European Union, mRNA therapies have been classified as gene therapy medicinal products.”

So, in the U.S. and Europe, mRNA therapies, as a group, are classified as “gene therapy medicinal products.” There’s simply no way around this. Yet to this day, mainstream media tries to “debunk” the reality of the COVID-19 jab.

Add to all this iniquity that all vaccines are factory bred in soups containing bovine afterbirth and kidney cancer cells from either one of two infants aborted in the forties and sixties.

To state that the covidiot quackzine did not introduce human DNA is a stupid lie.

Oh, and those fetuses both had genetic markers for so many defects and already so riddled with various cancers that they would probably not even have looked human, had they been born.

Now let me tell you about the metal fragments, parasite eggs, salmonella, glyphosate and aspartame and…

All in the academic literature, people earned their degrees with invisible research.

Robot Dave was instructed not to read those?

Can we get this effing robot switched off??

The reached target of vaccination always was complete immunisation.

Stopped with mRNA treatment.

Vaccines directly induce an immune response. The synthetic mRNA does not directly induce an immune response. It’s not a vaccine in any scientific sense.

Also, the injections themselves were contaminated with DNA, including the SV40 promoter. These DNA fragments can get incorporated into the cellular genome.

If the lipid/mRNA package enters ova, the DNA freight may incorporate into the germ line, with presently unknowable outcomes.

Vaccines induce an immune response. Full stop. That’s what they do. That’s how they work. “Directly” or “indirectly” is meaningless.

Also, the vaccines are not “contaminated with DNA.” They don’t have complete DNA strands, they have DNA fragments. But basically everything has DNA fragments.

Some early polio vaccines were contaminated with SV40 virus, but mRNA vaccines are not.

SV40 Promoter is not SV40 virus. Here’s a good article:

https://www.techarp.com/science/mrna-vaccines-contaminated-with-sv40-dna/

Here’s another:

https://www.techarp.com/fact-check/residual-dna-mrna-vaccines-health-risk/

Anti-vax scammers like Joe Mercola, Mike ‘Health Ranger’ Adams, Alex Jones, Sherri Tenpenny, etc. are murderous ghouls. By spreading the lie that vaccination is more dangerous than the disease it protects against, they’ve caused many, many unnecessary illnesses and deaths. I personally know a lady who is now a widow, raising her son alone, because she and her husband believed such lies.

But snake oil sales are booming:

Mercola:

Adams:

Jones:

Tenpenny:

“Directly” or “indirectly” is not meaningless. The biochemistry is distinct. The technology is orthogonal.

SV40 promoter can traffic into the nucleus of the cells it enters. The result of that depends on the neighboring genes. But whatever they are, they’ll be switched on.

Kevin McKernan North Carolina testimony about the dangerous levels and types of DNA in the Covid spike mRNA gene product. None of the discoveries are good news.

Paper on SV40 in the mRNA product.

The CDC admitted that 94% of the Covid deaths had an average of 4 co-morbidities. In normal times, those co-morbidities would have been given as primary cause of death, with the virus added as secondary player.

But the CDC sent out an advisory circular saying that Covid should be elevated to primary cause of death if it were present at all.

That rule caused the Covid death rate to falsely inflate by about a factor of 20.

Most the legitimate Covid deaths (~85%) occurred because effective early treatment was suppressed.

Corruption at the CDC

From Steve Kirsch’s Newsletter: A relay from Dr. Robert Malone.

Findings from the on-going independent audit of the CDC.

The bolding below is in the original

3. What the Audit Has Found So Far (as of late 2025)Preliminary briefings from the audit—though still not fully public—have already revealed disturbing patterns:

Data suppression: internal CDC archives contained multiple unpublished studies showing elevated risk ratios for developmental disorders following certain vaccine doses given within condensed time frames.Off-the-books relationships: over 40 CDC employees, active or recently retired, held consulting contracts or revolving positions with vaccine makers or NGOs indirectly funded by them.Altered statistical analyses: multiple audits of spreadsheets (recovered from backups) showed post-hoc data reclassification—especially redefinition of “unvaccinated” cohorts—to minimize detected associations with negative outcomes.Misuse of the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS):VAERS was allegedly treated as an image-management tool, not an epidemiological resource. Reports were automatically down-weighted through machine-generated “plausibility filters” that ignored temporal clustering of symptoms.Internal censorship: whistleblower testimonies described a culture of fear—scientists who questioned official narratives about autism, autoimmune rise, or chronic illness were ostracized or reassigned.https://s.w.org/images/core/emoji/17.0.2/svg/1f9e9.svg 4. The Autism ConnectionOne of the audit’s most sensitive focal points is the CDC’s 2000–2015 handling of autism data.

The auditors discovered:

Missing datasets related to racial subgroup analyses—data that, when restored, revealed disproportionately higher autism incidence among African-American boys receiving early MMR doses.Reclassification of autism cases into other diagnostic categories (like “developmental delay” or “learning disorder”) during certain surveillance periods.E-mails indicating top-level order to destroy draft datasets that contradicted public statements claiming “no evidence of causation.”This is particularly explosive given that, in late 2025, the CDC itself—now under Kennedy’s influence—has publicly admitted that “studies have not ruled out the possibility that infant vaccines cause autism.”

That disclosure alone vindicates years of dissenting experts whom mainstream institutions had vilified.

https://s.w.org/images/core/emoji/17.0.2/svg/2696.svg 5. Legal and Structural OutcomesAs of December 2025, the following actions are underway:

Criminal referrals to the Department of Justice for data falsification and destruction of public records. [This is huge; way overdue]…Public access initiative: upcoming release of roughly 10 terabytes of raw CDC epidemiological data spanning 1985–2023, hosted in a public repository with anonymization safeguards.This will be the first time in U.S. history that citizens and independent statisticians will be able to analyze federal health datasets without intermediary censorship.

Yes, Dave, now say that while you run your PCR machine so many cycles, the inventor guarantees you processable DNA fragments of any sort, given pure water as starting sample.

PURE WATER, DAVE!! Any sequence you wish for!

to the humans :

I only argue with this robot, because of we don’t, their groddamned talking computer will mark him up as the expert who refuted us all, using only approved sources.

My apologies,but this is how they count victories, by truth having fewer mentions than their lies.

And lo… One of the predecessor animals of humans lost the ability to make vitamin C

It took at least 40 million years to seize that ‘breakfast’ opportunity…

Kellogg’s All-Bran

Special K

Kellogg’s Rice Krispies

All with added vitamins

Etc

I prefer an English fry-up – the vitamin C is in the tomatoes and mushrooms…

…and the fat’s coating your arteries!

And yet I’m still here, hale and hearty. You should remember that – contrary to the nanny state directives – a little of what you fancy does you good.

There is emerging research that indicates fat does not do to us what we have been told.

Take your Lipitor, another safe and effective product brought to you by Pfizer.

I wouldn’t touch that with a ten-foot pole, either.

The generic seems to be working just fine.

Fat is good. It is pretty clear that the vilification of fat led to carbohydrate excess and the current unhealthy state of too many people.

A small proportion of the population is sensitive to various food components like salt, gluten, lactose, and cholesterol. Assuming that these are harmful to the general population is similar to the abuse of the linear no-threshold thesis of exposure. It is bad science and worse medicine.

I have seen too many of the edicts from on high reversed after a time, like margarine vs. butter or the blood pressure levels requiring pharmaceutical treatment, to have any faith at all in public health fads.

Fat is no unalloyed good. Saturated fat is good, polyunsaturated fat no so good.

Villification of saturated fat led to its replacement by polyunsaturated fats. Not so much carbs. Carbs are no problem in themselves.

Indeed, that was a careless statement on my part. No food component or food type is in itself good or bad. It all depends largely on quantity and balance, and on individual biochemistry and metabolism.

It is generally recognized that what is known as the “obesity epidemic” is, to a large degree, a consequence of carbohydrate intake, primarily refined sugar and processed grains.

Fats are a flavorful component of many foods. When they came under fire from the dietary police, they were replaced in many processed foods with sugar, to the joy of taste buds and adipose cells, and the detriment of neurons.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids are essential to neural health; in fact, a 5:1 ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 PUFAs is considered ideal. Unbalanced diets low in Ω-3 PUFAs have been linked to certain neural disorders, as have high concentrations of saturated fats.

Carnivores have been eating fat for hundreds of millions of years. The only way humans could not be adapted to need fat is if they are couch potatoes who would be just as unfit eating kale every meal.

About 5 years ago, the US changed the “ideal” diet, and said that we could eat eggs and butter again. (I can’t remember if they “allowed” bacon, as well.) I happened to be seeing my cardiologist a couple weeks later and asked him about the sudden volte face. He said that folks could eat all those cholesterol-rich foods. Just not folks like me, who have had an MI. Well, I started eating the occasional egg, and bacon, and use butter. My checkups have not changed, although I will need a tent in one of my bypass arteries sometime soon now. (He’s been saying that for 2 years, with attempt to schedule the procedure.)

I have promised myself that should I make it to my 90th birthday (12 years from tomorrow), I shall have a filet mignon wrapped in bacon.

Jim, I admit I am confused about lots of things, and cholesterol in general is one of those things.

As far as I recollect, the food you ingest is broken down in your gut into just a few things including amino acids, fatty acids and sugars. So eating cholesterol rich foods, or anything else, should be broken down into the things the body can use.

I know it’s very complicated, but some people seem to think that if you eat too much fat, say, bits somehow get into your bloodstream and clog up your arteries.

I assume that too much of this, and not enough of that, can lead to negative outcomes. Insufficient vitamin C, and you get scurvy. Common salt has no calorific value, but you can’t survive without it.

And so it goes. I sometimes wonder if the medical profession, being composed of humans, is subject to the same irrational thinking that other humans are, from time to time. Judging by the 180° turns from time to time (eggs are good, no wait, eggs are bad, no wait, they’re good again – maybe), it’s a possibility.

I’m still wondering whether your filet Mignon wrapped in bacon will just be converted into basic components your cells can use, and the rest eventually ejected from the far end of your intestinal tract as faeces.

The problem might be that if you suffer from anything at all after being so churlish as to question your expert’s advice – it’s obviously your fault! The experts are never wrong!

There is nothing to wonder. The medical profession is prone to all of the attributes of the human condition, and like any structure of authority, may even be more subject to abuse.

Indeed, as we have seen on many occasions, physicians can be held accountable not for their being right or wrong, but for deviating from the consensus, no matter how in error that consensus may be.

A new year’s toast (non-alcoholic in my case) to your achieving your goal and beyond!

Cholesterol and arterial plaques probably do not have the simple relationship that has been touted for many years, and no blanket injunction concerning fats seems appropriate. I eat fats, saturated and unsaturated, and do not trim the fat from my ribeye. My cholesterol numbers have remained well within the suggested range.

I recently read a letter presented to me on an academic site, from the lead physician on the fat/ cholesterol/ heart failure study way, way back. (’64? ’46?).

He said he was “incentivized” to lie. According to him, all their research had no firm conclusion, was not even designed for the final conclusion.

He spent some time apologizing for putting his family and livelihood before public interest. Says he’s old enough to be brave now.

I do not doubt this very much.

Physically impossible. But I do see that after Ancel Keys you missed every single publication on health.

“to discourage indulgence and even masturbation,”

When I learned that, I gave up corn flakes … & life improved (:-))

Story tip – h/t The Babbling Beaver

“One percent growth is enough.”

Not all the recommendations are revolutionary. They call for increasing the retirement age to 70, higher excise duties and a universal basic income for those who need it.

Yet there’s also plenty for the Earth in the authors’ list.

What’s in for the environment?

More public money to be spent on green economic stimulus packages through higher taxes, to finance measures against climate changeImposing taxes on fossil fuels like brown coal, in order to promote alternative energy sourcesEcological transformation in the workplace, including subsidies for employees who switch to a more eco-friendly jobIntroducing a tax system for consumption of natural resources. In plain terms, for consumers: More expensive flight tickets and higher heating costs https://www.dw.com/en/club-of-romes-new-book-reads-like-an-eco-manifesto/a-19549957

https://babblingbeaver.com/fake-news/

“”It’s not about less growth, but about a different growth“”

And being cold and hungry….

You left out… “… and be happy.”

The neo-Malthusian Club of Rome needs their feet to be held to the fire by evaluation of the utter failure of their policies. California seems to have been implementing Club of Rome policies for most of the 21st Century. The result has been that much of California’s energy infrastructure has been shut down. The state imports 25-30% of the electricity that it needs, while the Legislature pushes for more electrification of vehicles, heating and cooking.

Excessive regulation is causing two more refineries to shut down. This is removing over 280,000 barrels per day of gasoline and diesel production in California. With no pipelines to bring refined products into California, the government created shortfall will need to made up by shipping refined products into California from South Korean, Indian and Singaporean refineries. These are the only refineries outside of California which can produce the CARBOB blend which California mandates.

This utter lunacy is what the Club of Rome is pushing for the world.

It also eliminates the production of jet fuel from a location almost adjacent to LAX.

Yes, universal basic income even for those “unwilling to work” – HR 1, Alexandria Ocasio Cortez.

What they don’t seem to get is that to a cold, hungry person, a tree is not to be hugged, but rather burned, and the nearest endangered species is supper. Environmentalism is a luxury of the affluent.

Well written! I would like to suggest you acquire the book by Dr. Levy, “Curing the Incurable.” It’s available on Amazon. I stumbled onto it by accident. What shocked me was discovering that it was known in the 1930’s that intravenous C would stop the progression of polio. There have been numerous papers on this subject. The same is true of measles, mumps, pertussis. Our inability to create our own vitamin C has far reaching effects. Our medical ignorance of this has caused incredible amounts of sadness.

I’ve been taking vitamin C in “mega doses” since 1975. I’m now a hard convert to liposomal delivery of C. The phosphatidylserine molecules surrounding it are the same as those in the cell membrane, thus transport into the cell requires no energy expenditure, no electron exchange. It also isn’t purged as quickly from the blood, some studies have claimed that it remains 5x longer in the blood. With the effective buffering it’s easy to take 3,000 mg and more of ascorbic acid with no side effects. Sodium ascorbate is also buffered and works well as additional component to a NaCl nasal rinse. It works as a salt substitute in some of my recipes as well.

A project for genetic engineers- fix our DNA so we can make vitamin C?

You missed the downside to the liver of vitamin C production.

That means even more work for the genetic engineers. 🙂

How about “we” stop screwing around with genes?

That would be best but it won’t happen. AI and genetic engineering will happen big time. The future will be like science fiction.

Sounds like there is a whole set of adaptations that would need to be reversed, all at once, with more knock-on effects cascading the difficulties. I’d say leave it alone. There are much more worthwhile projects with fewer complications.

I was joking of course about the genetic engineers. I’d be very cautious of tinkering with human DNA by anyone for just the reasons you mention. I’m more into healthy life style, good food, lots of sex, etc. Whatever it takes to naturally be healthy- then you die, eventually. 🙂

The whole story was about how we outsourced the production making us more efficient. We’re not dying from liver disease as are our cats. If we have liver disease, its almost always ‘a problem with our poisons.’ Unlike the other mammals which have these stated Vitamin C and H2O2 problems.

I do wonder if a high vitamin c diet would relieve the stress on a cat’s liver. The body does tend to stop producing what it already has in excess.

Confirms what I have understood for years. Now I have the science behind it.

The FDA RDA is what is needed to ward of scurvy, not optimum health.

My uncle claims he has halted his cancer (for decades) with Vitamin C.

I take 10 grams per day. Be aware you have to work up to that level as too much too fast causes gastro problems.

I got Covid. It lasted 24 hours with symptoms of a cold.

I have not gotten the flu in the past 60 years.

Part of that was a bout with Asian flu (nasty beasty) when I was 3 or 4.

I rarely get colds, too.

I too rarely get colds, even when living with children, and have never had the flu or COVID. I don’t take supplements of any kind. I eat lots of meat and fruit, drink lots of juice, but because I want to, not because of any diet decisions. I make lots of other dietary decisions based entirely on what I want, not what others say. I imagine it’s more luck-of-the-draw than anything else.

Genetics plays its part, yes.

My maternal grandfather died at 99. The day he died he smoked 2 packs of Camels, a habit he had from the age of 14.

On my father’s side we have alternate generations of prostate cancer and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BHP). No cases of lung cancer as far back as we can see.

So yes, luck of the draw plays in.

An interesting article until you wrote “So far, so good. Then Antarctica drifted over the South Pole, the Antarctic ice sheet appeared, and the current ice age began.”

Antarctica moved to its current position over the South Pole about one hundred million years ago and has moved very little since. Our glacial ages, which you call “ice ages” began about 3 million years ago and for the first 2 million years, occurred every 40,000 years or so. About 1 million years ago, they began occurring every 100,000 years or so. Whatever the cause for intermittent glacial ages we are now experiencing and the change in their periodicity, it had nothing to do with movement of Antarctica.

I’m no geologist but I read just recently that some cooling actually began 30 M years ago.So the Antarctica moving over the south pole may be contributing to the cooling. I don’t think there is as of yet a consensus about the “ice ages”- not that a consensus is proof, as we know when it comes to CO2 and warming.

The current ice age began 34 Ma, when deep channels opened between Antarctica and South America and Australia, forming the Southern Ocean. North America joined the glaciation when the Isthmus of Panama formed about 3 Ma.

Who’d have thunk it, eh?

Eat healthy foods, take exercise outdoors in the sunshine and boom: you will have healthy levels of Vitamins C and D, plus zinc.

None of this pill-popping malarkey.

Cherries, gooseberries and blackcurrants in June. Plums in July and August. Apples from August to November. Blackberries August and September.

Tomatoes from July to October. Brussels Sprouts, Red Cabbage and Kale in the autumn and winter, along with red potatoes.

Overwintered chard and freshly sown mustard from March to June.

Who prefers staying healthy eating delicious tomatoes, plums, apples etc etc vs popping some tasteless pill from Amazon?

Idyllic, but impractical for most. I forage as much as I can, but it’s not remotely enough to provide all the nutrients I need. Supplements are an unfortunate necessity for me, and an unquestionable one for anyone who lives in a city.

We are fortunate to have modern airfreight and produce all year round.

FAQ: What is the upper limit (tolerance) for vitamin-C supplementation?

Here’s an answer*:

That works out to ~ 40-g/day, week-in & week-out.

Not a typo: Forty grams per day, on average.

That’s comparable to the level in a mountain goat. And perhaps for the same reason specified here: an advanced-cancer patient is overwhelmed by fermentation byproducts.

Wishing you all Long & Healthy-Active Lives …

… and a Prosperous (Productive) 2026 A.D.!

— RLW

*Source:

Caveat lector….A little bit of knowledge can be dangerous.

People with a UTI get over it faster. People who don’t have a UTI and take Vit C get more UTIs…..People who take Vit E, a strong anti-oxidant, have higher rates of CAD….Just about every disease in the textbook of medicine is associated with anemia. That doesn’t mean a transfusion will cure any of them.

And what about those of us who already have been diagnosed with CAD? Should we avoid Vitamin E?

But, but, but … what would Nick say?

He would say build more WTGs and SVs and drive an EV and all of your health problems are cured.

QED

Humor – a difficult concept.

— Lt. Saavik

I’ve gone the better part of a week without seeing anything from Nick. It’s New Year’s Eve (here). I really don’t care what he’d say on this topic.

Ever since I heard about the old time sailor men, who ate the same again and again. (Reminds me of a menu at a Holiday Inn.) Back in Jr. High and was taught that’s why they got scurvy from a lack of vitamin C, I’ve been a vitamin C fanatic and have received a lot of compliments from doctors on my health.

Captain Blight of Bounty fame proved it. His voyage, due to his dietary supplement (sauerkraut and orange extract) resulted in no cases of scurvy.

The reason you Americans called us Limeys was due to the Royal Navy giving its sailors lime juice to prevent scurvy.

Keeping highly trained seamen alive was vitally important to the Royal Navy and Britain.

That is so interesting!

The formula for vitamin C:

C6H8O6

SIX CARBONS!!!

How can that be good for us? /sarc

And it’s full of H8! Terrible!

You deserve a very Happy New Year.

I doubt that we need that much vitamin c because those who follow a carnivore diet do not seem to have any adverse effects attributed to vitamin c deficiency. I have 80 grams of raspberries each day and get some in meat but I have no adverse affects from following a low carb diet with little fruit.

Regarding what some have said about having vitamin deficiency and catching covid flu etc., I believe that those who are hospitalised by these thing have metabolic syndrome and poor blood sugar or/and obesity not vitamin c deficiency.

I am missing a comparison to monkeys or chimpanzees. By the way, Darwin probably developed his evolution theory before he had children. Primates? Pigs must be our closest relatives 🙂

I didn’t realise you knew the mother-in-law (:-))

It is my understanding that vitamin D isn’t a vitamin, but rather a steroid. (And, yes, I know not all steroids are bad.)