Guest essay by Eric Worrall

A new study claims that Scottish sea birds are being forced to diversify their diet by a shortage of their favourite prey species. But in my opinion the study ignores other issues, such as chemical pollution and long term radioactive contamination in regions adjacent to the study location.

Warmer water signals change for Scotland’s shags

…

Three decades of data from the Isle of May, off Scotland’s east coast, found that the proportion of sandeels – the bird’s usual fayre – declined by 48% between 1985 and 2014. Over the same period, the number of other fish prey in the diet increased, from an average of just one species per year in 1985 to eleven in 2014.

…

The North Sea is one of the most rapidly warming marine ecosystems on the planet, and warmed by 0.037 degrees Celsius per year between 1982 and 2012. Lead author, Richard Howells, explained that the study, “ties in with many observations of changes in the abundance, distribution and phenology of many species in the North Sea, and a decline in the availability and size of sandeels.

“Climate models predict further increases in sea surface temperature and weather variability in the region, with generalisation in shag diet, one way in which this species appears to be responding to this change.”

Short-term weather conditions also impacted on the bird’s ability to feed, with “windier conditions on a daily basis linked to fewer sandeel in the diet. This may affect the ability of parents to successfully feed their chicks,” Howells said.

”Changes in the prey types consumed by this population suggest that adults may now be hunting across a broader range of habitats than they did in the past, such as rocky habitats where they can find the Rock Butterfish. Such changes may alter interactions with potential threats, such as small-scale offshore renewable developments.”

…

Read more: https://www.ceh.ac.uk/news-and-media/news/warmer-water-signals-change-scotland’s-shags

The abstract of the study;

From days to decades: short- and long-term variation in environmental conditions affect offspring diet composition of a marine top predator

Richard J. Howells, Sarah J. Burthe, Jon A. Green, Michael P. Harris, Mark A. Newell, Adam Butler,

David G. Johns, Edward J. Carnell, Sarah Wanless, Francis Daunt

ABSTRACT: Long-term changes in climate are affecting the abundance, distribution and phenology of species across all trophic levels. Short-term climate variability is also having a profound impact on species and trophic interactions. Crucially, species will experience long- and short-term variation simultaneously, and both are predicted to change, yet studies tend to focus on only one of these temporal scales. Apex predators are sensitive to long-term climate-driven changes in prey populations and short-term effects of weather on prey availability, both of which could result in changes of diet. We investigated temporal trends and effects of long- and short-term environmental variability on chick diet composition in a North Sea population of European shags Phalacrocorax aristotelis between 1985 and 2014. The proportion of their principal prey, lesser sandeel Ammodytes marinus, declined from 0.99 (1985) to 0.51 (2014), and estimated sandeel size declined from 104.5 to 92.0 mm. Concurrently, diet diversification increased from 1.32 (1985) to 11.05 (2014) prey types yr-1, including members of the families Pholidae, Callionymidae and Gadidae. The relative proportion of adult to juvenile sandeel was greater following low sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the previous year. In contrast, the proportion of Pholidae and prey richness were higher following high SST in the previous year. Within a season, the proportion of sandeel in the diet was lower on days with higher wind speeds. Crucially, our results showed that diet diversification was linked to trends in SST?. Thus, predicted changes in climate means and variability may have important implications for diet composition of European shags in the future, with potential consequences for population dynamics.

Read more: http://www.int-res.com/abstracts/meps/v583/p227-242/

My biggest issue with this study is that the authors are calling climate, based on data from just one location.

But delving deeper, there is another problem;

…

Environmental covariates

Annual sandeel proxies

As there are no long-term abundance data for the local sandeel population upon which Isle of May shags feed, we utilised 3 environmental proxies of sandeel availability.

Sea Surface Temperature (SST): SST affects sand-eel recruitment via the bottom-up effects of temperature on the availability of key copepod prey (Wright & Bailey 1993, Arnott & Ruxton 2002, van Deurs et al. 2009). Monthly SST data were obtained from the German ‘Bundesamt fur Seeschifffart und Hydro- graphie’ (www.bsh.de). Following Frederiksen et al. (2004), we calculated the mean of February and March SST for an inshore area surrounding the Isle of May (bounded by ca. 56°0’ to 56°4’N, and 2°7’ to 2° 3’ W), overlapping with the summer foraging range of this population (Bogdanova et al. 2014).

Calanus abundance: calanoid copepods, in particular the eggs and nauplii of Calanus finmarchicus, are of key importance to survival probability of early life stages of sandeels (Macer 1966, Arnott & Ruxton 2002, van Deurs et al. 2009). We analysed 1597 samples from the continuous plankton recorder (see Reid et al. 2003 for an overview) taken from a bounding box surrounding the Isle of May (55° to 58° N, 3° 0° E), between 1984 and 2014. This box is larger than the summer foraging range of the study population, but ensured there were sufficient data for the analysis. We included 2 measures of Calanus: C. finmarchicus (stages V to VI) abundance (as a proxy for C. finmarchicus egg production; van Deurs et al. 2009) and Calanus nauplii abundance (for all species combined, as species-specific abundances were unavailable). For each measure, we calculated mean monthly abundance from February to May, since these months constitute the principal period of larval sandeel feeding (Wright & Bailey 1996, van Deurs et al. 2009).

Lagged covariates: the abundance of 1+ group sandeels is dependent on conditions experienced as 0 group fish in the previous year (Arnott & Ruxton 2002). We therefore considered SST, C. finmarchicus (stages V to VI) abundance and Calanus nauplii abundance lagged by 1 yr as indices of the abundance of 1+ sandeel in the current year.

…

Read more (full text, p230-231): http://www.int-res.com/articles/meps_oa/m583p227.pdf

The researchers didn’t have a direct measure of the availability of sand-eels – they used proxies, including sea surface temperature, to estimate the local sand-eel population. They then concluded that sea surface temperature was the key issue.

There are additional issues. The Isle of May is located near the Scottish capital city Endinburgh in the mouth of the Firth of Forth, an estuary discharging several local rivers.

The Firth of Forth has seen several serious pollution scandals.

Back in 2007, a pump breakdown caused 170,000 tons of raw sewage to discharge into the estuary. The Firth of Forth also suffers substantial industrial pollution, including substantial levels of resinous plastics pre-cursors.

In 2014, Dalgety Bay on the shores of the Firth of Forth, just over the water from Edinburgh, was subject to a radiation scare – the beach was closed to the public, so it could be decontaminated by the Ministry of Defence.

I don’t know how much impact all this contamination has on the local wildlife. There is a lot of water in Firth of Forth estuary to dilute all that pollution. The radioactive contamination might have been mild – it doesn’t take much radiation to get bureaucrats excited.

On the other hand, the sea birds are at the top of a long food chain which stretches throughout the estuary. Apex predators and their immediate prey are often the most at risk of biomagnification of toxins through the food chain.

In my opinion, given the limited scope of the study – just one location – the indirect measurement of a key factor (population of sand eels), and the risk that other factors such as long term contamination with radioactive waste and other pollutants could have driven changes in diet, it seems premature to suggest climate change is the main culprit, without performing further studies in other hopefully less contaminated locations.

Update (EW) – Roy Mc provides evidence that sandeel fishing is the culprit, overfishing of sandeel is causing a decline in Scottish seabirds.

Just for the record, is that a pressured or unpressured Scottish Shag (Phalacrocorax aristotelis). in the lead photo? It could be important for us to know. He looks quite happy in either event.

Like all cormorants, shags’ diet is diverse. They’ll eat just about any fish they can catch. Where present, they even eat sea snakes. Like sea lions, human fishers don’t like their competition.

In fact, cormorants evolved from inland birds, so can even feed in freshwater if need be.

Chinese and Japanese fishermen use them in lakes.

In recent years, off the South West tip of Scotland in Galloway, for example, inshore declines of sand eels have had nothing to do with virtually imperceptible changes in water temperature. The most significant impacts have been caused by a combination of aggressive trawling in feeding grounds and silt run off from local rivers in a succession of spate years contaminating the same inshore areas. This, in turn, has led to increased numbers of inshore eel feeding birds, such as cormorants on the west coast, being driven inland and devastating nearby fisheries, lochs and rivers. In the long term, a few very wet years close together are nothing unusual in the local precipitation record. It’s called ‘natural variation’. The eels just move off to more hospitable environs elsewhere out of reach of the inshore bird populations that normally predate them. The actions of trawler skippers might be deemed ‘unnatural variation’. The problem may be partially man made but, sorry Griff, you can’t pin this ‘shaggy dog story’ on global warming.

As if shags are the least bit endangered, anyway. They’re rated as “Least Concerned” in conservation status in the IUCN Red List. Their range is large, breeding in western and southern Europe, southwest Asia and north Africa. Its fellow member of the same genus, the great black cormorant, is distributed even more widely. Their ranges overlap:

Indeed. The Shag is a common breeding species in the Mediterranean where water temperatures are rather more than a degree warmer than in Scotland.

Good point.

Warmer is better for shaglings.

“Warmer is better for shaglings.”

Gees, I had to read carefully a few times !!

I have often enjoyed Griff’s contributions, sometimes interesting or provocative, and sometimes on aspects of the “it’s because of our carbon dioxide emissions/global warming” subjects about which I don’t know enough to comment. I usually read his comments and the responses to see how the arguments are being made. This latest thread has however fatally damaged his credibility in my eyes. He seems to have ideological blinkers on.

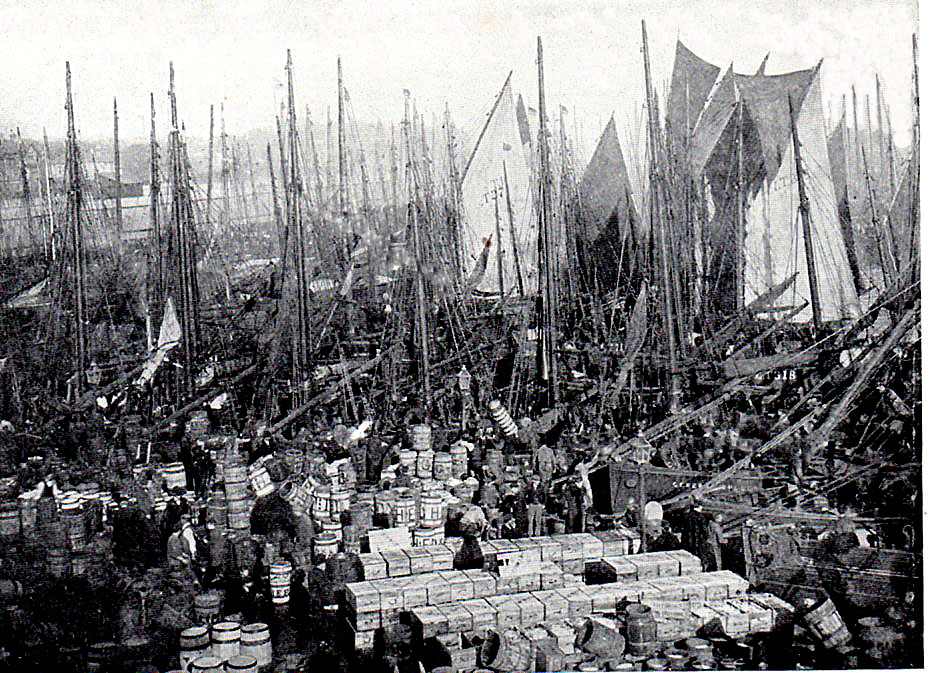

Three generations of my paternal family were herring fishermen. Of the next lot, my uncle was a skipper on a white fish trawler (and subsequently was the ‘fishing’ skipper on a fisheries research vessel), and my father was meteorologist, sometimes on weather-ships. There isn’t much I haven’t been told about fishing in Scottish waters.

Herring were over-fished even in the days of the drifters, although the collapse of the Baltic trade for salted herring after revolution and wars assisted in the decline of the industry. Fast-forward to the 1970s and the tottering UK government, in an attempt to garner votes, made its idiotic protest about Iceland’s perfectly sensible 200-mile foreign fishing boat exclusion zone due to the marginal Labour seats in Hull and Grimsby, home ports for the major English deep-sea fleets. We should have instead said “What a jolly good idea, let’s do the same”. But having done what we did, as a member of the EU, it was quotas all round for foreign boats, and the decline of the UK industry accelerated. UK fishermen couldn’t catch herring for people to eat, and seine net boats from Denmark were scooping out herring to feed to pigs, and the bacon was then being sold in the UK. UK pig farmers and fishermen were going out of business at the same time. Marvellous, and the UK herring fishery collapsed. I can remember standing on the pier in Lerwick watching the boats and being astonished at the tiny mesh on the nets.

Subsequently, with a non-food demand for oily fish and the herring wiped out, the sand-eel fishery took off, again with the Danes getting big quotas, and you don’t have to be a genius to work out why bird and larger fish species that eat sand-eels are in decline when the fishermen granted the quotas can’t actually achieve them.

Throughout all this, the sclerosis in the EU fisheries management has been painful to watch. Boats throwing already dead fish overboard (discards) as to land them would have violated their quotas, is just immoral. It’s taken decades to establish conservation no-fish zones, and have regulations about mesh designs and sizes brought in, with Scottish fishermen and researchers often leading the way and the EU dragging its heels.

No Griff, neither you nor the authors of misguided papers can blame “climate change”, however “on-message” that might be . As well as natural periodic variations, sand-eels are in short supply because they’re being scooped out of the sea too fast. Better to leave them there for the sea-birds and bigger (tasty) fish to eat. The only anthropogenic factor hammering sand-eel populations in UK waters is the ruddy EU fisheries management policies.

Warm shags in Scotland…I did enjoy them, sadly now a distant (happy) memory.

The common cormorant or shag

lays its eggs in a paper bag.

The common Gallinule or Rail

Lays its eggs in a plastic pail.

(crickets)

Thanks, was trying to rember the two opening lines. The rest show that shags may be the climate scientists of the avian world.

‘You follow the idea, no doubt?

It’s to keep the lightning out.

But what these unobservant birds

Have never thought of, is that herds

Of wandering bears might come with buns

And steal the bags to hold the crumbs.’

Christopher Isherwood (which reminds us that ‘Money Makes The World Go Round’)

I used to holiday with my family on the east coast in the 70s/80s and when they started fishing for sand eels to use for agricultural fertiliser the numbers dropped like a stone and so did the number of others that fed on them.

Fishing for fertilser used to happen accidentally. In the 1920s My grandfather failed to sell one catch of herring at the market in Lowestoft (the traditional winter season when the scottish herring fleet would go south). A local farmer bought the lot and spread the unprocessed herring on his fields. The greedy gulls would come and gorge themselves to the point where they couldn’t fly, then waddle around depositing their guano.

A reminder of how bountiful the sea was.

given that picture of bounty that once was, “was” is the opporative word, and “overfished” should be in the same sentence.

I have often enjoyed Griff’s contributions, sometimes interesting or provocative, and sometimes on aspects of the “it’s because of our carbon dioxide emissions/global warming” subjects about which I don’t know enough to comment. I usually read his comments and the responses to see how the arguments are being made. This latest thread has however fatally damaged his credibility in my eyes. He seems to have ideological blinkers on.

Three generations of my paternal family were herring fishermen. Of the next lot, my uncle was a skipper on a white fish trawler (and subsequently was the ‘fishing’ skipper on a fisheries research vessel), and my father was meteorologist, sometimes on weather-ships. There isn’t much I haven’t been told about fishing in Scottish waters.

Herring were over-fished even in the days of the drifters, although the collapse of the Baltic trade for salted herring after revolution and wars assisted in the decline of the industry. Fast-forward to the 1970s and the tottering UK government, in an attempt to garner votes, made its idiotic protest about Iceland’s perfectly sensible 200-mile foreign fishing boat exclusion zone due to the marginal Labour seats in Hull and Grimsby, home ports for the major English deep-sea fleets. We should have instead said “What a jolly good idea, let’s do the same”. But having done what we did, as a member of the EU, it was quotas all round for foreign boats, and the decline of the UK industry accelerated. UK fishermen couldn’t catch herring for people to eat, and seine net boats from Denmark were scooping out herring to feed to pigs, and the bacon was then being sold in the UK. UK pig farmers and fishermen were going out of business at the same time. Marvellous, and the UK herring fishery collapsed. I can remember standing on the pier in Lerwick watching the boats and being astonished at the tiny mesh on the nets.

Subsequently, with a non-food demand for oily fish and the herring wiped out, the sand-eel fishery took off, again with the Danes getting big quotas, and you don’t have to be a genius to work out why bird and larger fish species that eat sand-eels are in decline when the fishermen granted the sand-eel quotas can’t actually achieve them.

Throughout all this, the sclerosis in the EU fisheries management has been painful to watch. Boats throwing already dead fish overboard (discards) as to land them would have violated their quotas is just immoral. It’s taken decades to establish conservation no-fish zones, and have regulations about mesh designs and sizes brought in, with Scottish fishermen and researchers often leading the way and the EU dragging its heels.

No Griff, neither you nor the authors of misguided papers can blame “climate change”, however on-message that might be . As well as natural periodic variations, sand-eels are in short supply because they’re being scooped out of the sea far too fast. Better to leave them there for the sea-birds and bigger (tasty) fish to eat. The only anthropogenic factor hammering sand-eel populations in UK waters is the ruddy EU fisheries management policies. Take your blinkers off Griff, you’ll find you can see a lot more.

This EU funded behemoth didn’t help African fishermen either.

https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world-s-largest-fishing-vessel-arrives-in-dublin-1.1098081

http://britishseafishing.co.uk/atlantic-dawn-the-ship-from-hell/

“He seems to have ideological blinkers on.”

WOW..news to me……. I never realised that !! 😉

Can someone please turn the temperature down 0.037 degrees it’s way too hot !

Come BREXIT, the UK will reestablish is fishing zones, let’s hope the birds can wait…..

Let’s hope you’re right SR and UK does not give them away in another pathetic attempt to curry favo(u)r with EU. May seems to be doing her best to mess things up and she has form.

Bah, apologies for double post. WordPress seemed to get stuck overnight.

This is what the Scottish Government has to say about Sand Eel populations and fishing.

It seems the North Sea Sand Eel population is vulnerable to over fishing. In contrast the Shetland Sand Eel fisheries have been controlled since the late 1980s because of the damage being done to other predators, Puffins in particular if my memory is correct. Minor changes in water temperature seem to be less of a problem than over fishing.

Forgot the link

http://www.gov.scot/Topics/marine/marine-environment/species/fish/sandeels

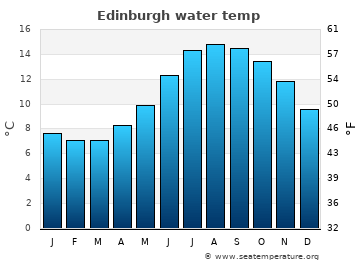

Edinburgh ocean temperatures, winter 6C to summer 14C, and 1.4C is going to kill the sandeel?

hmmm. Several studies have confirmed that oceanic flora and fauna, just like land flora and fauna, follow decadal oceanic oscillations. I am willing to bet that some of this shad downturn could be related to a natural decadal migration pattern. The only reason why the Padific salmon pattern was identified was because of fishing vessal logs from way back demonstrating such a pattern.

using temperature as a proxy for food supply and then concluding temperature affects population is mathematical nonsense. this. paper should have been rejected for a fundamental mathematical error in experimental design.

Late to this discussion, but comments above are very interesting, with those from SONOFAMETMAN’S worth reading twice. Here is an older paper showing a population explosion from reduction of herring and mackerel populations. (Sherman, K., C. Jones, L. Sullivan, W. Smith, P. Berrien and L. Ejsymont. 1981. Congruent shifts in sand eel abundance in western and eastern North Atlantic ecosystems. Nature. 291:486-489). I also seem to remember an older U.S. paper about shifts with temperature. In the Gulf of Mexico cormorants compete more with fish than with other birds, except for the few loons, grebes and mergansers in winter, and others in crawfish ponds. I get in trouble with friends of birds by kidding them about bringing back the feather industry to save them and fish, but some lack a sense of humor. I read about his run in about lack of humor in one of Roy Spencer’s book so I am in good company.

This was in Ireland, but food must be important.

Tománková, I., C. Harrod, A. D. Fox and N. Reid. 2013. Chlorophyll-a concentrations and macroinvertebrate declines coincide with the collapse of overwintering diving duck populations in a large eutrophic lake. Freshwater Biology. doi.10.1111/fwb.12261. The ducks ended up in a more northern climate, so warming was also invoked, but Gulf of Mexico ducks go north every summer.

While the paper was not studied adequately, it lacks the Sherman, et al., paper, but they know about Ashmole’s halo: direct evidence for prey depletion by a seabird. However, this caveat (among others) sounds important—“We selected C. finmarchicus abundance as a proxy of egg production, since eggs and nauplii of this species are key prey of younger age classes of sandeel (van Deurs et al. 2009). Thus, there are multiple intermediate steps connecting C. finmarchicus and sandeel abundance that may each serve to weaken the relationship between them. ”

This is also an interesting book on the subject.

Hall, S. T. 1999. The Effects of Fishing on Marine Ecosystems and Communities. Blackwell Science, Oxford. 274p.