One point struck me, reading Anthony’s fascinating account of his meeting with Bill McKibben. Bill, whose primary expertise is writing, appears to have an almost magical view of what computers can do.

Computers are amazing, remarkable, incredibly useful, but they are not magic. As an IT expert with over 25 years commercial experience, someone who has spent a significant part of almost every day of my life, since my mid teens, working on computer software, I’m going to share some of my insights into this most remarkable device – and I’m going to explain why my experience of computers makes me skeptical, of claims about the accuracy and efficacy of climate modelling.

First and foremost, computer models are deeply influenced by the assumptions of the software developer. Creating software is an artistic experience, it feels like embedding a piece of yourself into a machine. Your thoughts, your ideas, amplified by the power of a machine which is built to serve your needs – its a eerie sensation, feeling your intellectual reach unfold and expand with the help of a machine.

But this act of creation is also a restriction – it is very difficult to create software which produces a completely unexpected result. More than anything, software is a mirror of the creator’s opinions. It might help you to fill in a few details, but unless you deliberately and very skilfully set out to create a machine which can genuinely innovate, computers rarely produce surprises. They do what you tell them to do.

So when I see scientists or politicians claiming that their argument is valid because of the output of a computer model they created, it makes me cringe. To my expert ears, all they are saying is they embedded their opinion in a machine and it produced the answer they wanted it to produce. They might as well say they wrote their opinion into a MS Word document, and printed it – here is the proof see, its printed on a piece of paper…

My second thought, is that it is very easy to be captured by the illusion, that a reflection of yourself means something more than it does.

If people don’t understand the limitations of computers, if they don’t understand that what they are really seeing is a reflection of themselves, they can develop an inflated sense of the value the computer is adding to their efforts. I have seen this happen more than once in a corporate setting. The computer almost never disagrees with the researchers who create the software, or who commission someone else to write the software to the researcher’s specifications. If you always receive positive reinforcement for your views, its like being flattered – its very, very tempting to mistake flattery for genuine support. This is, in part, what I think has happened to climate researchers who rely on computers. The computers almost always tell them they are right – because they told the computers what to say. But its easy to forget, that all that positive reinforcement is just a reflection of their own opinions.

Bill McKibben is receiving assurances from people who are utterly confident that their theories are correct – but if my theory as to what has gone wrong is correct, the people delivering the assurances have been deceived by the ultimate echo chamber. Their computer simulations hardly ever deviate from their preconceived conclusions – because the output of their simulations is simply a reflection of their preconceived opinions.

One day, maybe one day soon, computers will supersede the boundaries we impose. Researchers like Kenneth Stanley, like Alex Wissner-Gross, are investing their significant intellectual efforts into finding ways to defeat the limitations software developers impose on their creations.

They will succeed. Even after 50 years, computer hardware capabilities are growing exponentially, doubling every 18 months, unlocking a geometric rise in computational power, power to conduct ever more ambitious attempts to create genuine artificial intelligence. The technological singularity – a prediction that computers will soon exceed human intelligence, and transform society in ways which are utterly beyond our current ability to comprehend – may only be a few decades away. In the coming years, we shall be dazzled with a series of ever more impressive technological marvels. Problems which seem insurmountable today – extending human longevity, creating robots which can perform ordinary household tasks, curing currently incurable diseases, maybe even creating a reliable climate model, will in the next few decades start to fall like skittles before the increasingly awesome computational power, and software development skills at our disposal.

But that day, that age of marvels, the age in which computers stop just being machines, and become our friends and partners, maybe even become part of us, through neural implants – perfect memory, instant command of any foreign language, immediately recall the name of anyone you talk to – that day has not yet dawned. For now, computers are just machines, they do what we tell them to do – nothing more. This is why I am deeply skeptical, about claims that computer models created by people who already think they know the answer, who have strong preconceptions about the outcome they want to see, can accurately model the climate.

Discover more from Watts Up With That?

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Too funny. Watching “Thunderbirds” (Classic) an episode using computers to control a spacecraft’s re-entry to Earth. I think this was well before Apollo.

lsvalgaard June 7, 2015 at 6:20 pm

Of course, the instructions have to be correct, but that is a people problem, not a computer problem.

Followed by:

lsvalgaard June 7, 2015 at 7:50 pm

They are not the ‘personal opinion’ of the constructor, and they do not just ‘influence’ the construction, they determine the model. There is nothing left of the person in the model, it is pure and hard science.

You can’t have it both ways 😉

Yes I can, because it is people who decide what goes into the model. They may try to do it correctly, but the consensus may also be faulty.

but the consensus may also be faulty.

In other words, the models are susceptible to both human error and human bias. They may well get better over time as the actual scientific process grinds the errors out of them. But this doesn’t change the perception of the general public which is that the results of computer models (any computer models) are accurate. Some are, some aren’t. In the case of climate models, all the errors, or biases, or combinations thereof seem to run in the same direction; hot. The IPCC said as much in AR5, who am I to argue? But this doesn’t change the fact that the general populace puts more faith in climate models than they have earned, and those who seek the support to advance their political agenda are not hesitant to take advantage of the public’s misplaced trust.

Not human error and certainly not human bias. The errors are errors of the science and not of any humans and nobody puts bias into the model. Doing so would be destructive of the reputation and career of the scientists involved.

I was once a gunner in the Royal Danish Artillery. Let me tell you how we zero in on a target. The first salvo may fall a bit short [climate models too cold], so you increase the elevation of the tube and fire a second salvo. That salvo may fall too far behind the target [climate models too hot]. So you adjust the elevation a third and final time and the next salvo will be on the target.

Lief,

IPCC’s models use ECS figures from 2.1 degrees C to 4.5 C. All are demonstrably too high. Hence, all the model runs are prime instances of GIGO, quite apart from all the other problems with the tendentious models. There is no evidentiary basis whatsoever for any ECS above 1.2 C. Thus, those who say that they are designed, or at least their inputs are so designed, to produce the results which they show are thus entirely correct.

The ECS is output of the models, not input to them.

From IPCC: “equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) were calculated by the modelling groups”.

Doing so would be destructive of the reputation and career of the scientists involved.

I didn’t say it was deliberate, did I? The root cause could easily be completely innocent.

In any event, your statement is untrue if the general modeling community on a given subject are all making similar errors/biases as there would be no one left to call BULLSH*T. Of course that would be unlikely to happen as then all computer models of the climate would exhibit errors in the same direction when compared to observations.

Oh wait…

The first salvo may fall a bit short [climate models too cold],

As long as I have been following this debate, the models have been running hot. When was it that they were too cold?

Leif,

Calculated by the modeling groups mean they were input. How does a GCM compute ECS? In real science, that would be done by observation of reality.

Why does IPCC have no model runs with ECS of 1.5 to 2.1, despite its lowering of the bottom of the range to 1.5, because observations of reality have shown anything above 2.0 to be impossible?

Read the IPCC assessments on this. The ECS is calculated by the models. Not an input. Why is it that people can’t get the basics even halfway correct? Where did you get misled into believing that ECS was an input parameter? Who told you that?

Lief,

My point is that, however derived, the ECS numbers in the worse than worthless GCMs are obviously anti-scientific and unphysical. If they’re derived from the models, that makes the models even worse, if that’s possible. But they are in effect inputs because the absurd GCMs are designed to produce preposterous CO2 feedback effects.

Actual ECS, as derived from observations of reality, are about the same 1.2 degrees C that would happen without any feedbacks, either positive or negative:

http://climateaudit.org/2015/03/19/the-implications-for-climate-sensitivity-of-bjorn-stevens-new-aerosol-forcing-paper/

You evade the issue: where did you learn that ECS was input and not derived from the models?

Who told you that?

Leif,

I’m evading nothing. The fact is that the ECS numbers in all IPCC models are ludicrously high. Just as the fact that they run way too hot. You think that’s just an accident. I don’t.

You are evading the fact that the climate models are easily demonstrated pieces of CACCA.

Nonsense, I have always said that the models are no good, but you are still evading my question: where did you learn that ECS was input rather than output?

Leif,

That would be by looking at their code.

Have you done that? Which module? What line?

Perhaps I should elaborate.

The GCM’s code is designed to produce high ECS, hence saying that ECS is not an input is a distinction without a difference, as the logicians put it.

Have you seen the design documentation for ECS where it says that the code was designed for producing a high value? And how did the design document specify that the calculation should be done to produce a high ECS? Otherwise, it is just supposition.

Leif,

Which GCM do you have in mind.

The models which I’ve looked at are only those with the lowest ECS, ie the two (I think) with input/outputs of 2.1.

And which models would that be? Which module? Line number?

Not a supposition. An observation, since the ECSes in even the lowest ECS models do not reflect reality.

Models: INM-CM3.0 and PCM.

http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/full/10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00564.1

lsvalgaard

June 7, 2015 at 10:02 pm

That is not how the climate models have been concocted. All their shots are over the target and none under, yet they stick by the obviously too hot models, even though Mother Nature has shown them to be off target.

looncraz June 7, 2015 at 12:46 pm:

“The modelers set out to correct the cold-running nature of the earlier models ”

You see, it is not what you know that gets you in trouble, it is what you know that ain’t so.

Leif,

Did you mean to reply to me here?

possibly. WordPress is not too good connecting replies to comments. But to clarify: the early models were running too cold.

Attempting to model a physical system where most of the physics is unknown, is a farce. We never will have a complete understanding of every interaction that controls climate.

Finite element modelling where the elements are so huge as to entirely miss key elements such as thunderstorms, is an even greater farce. It will be hundreds of years, if ever, before computers are powerful enough to cope with elements small enough to consider all relevent details of the climate system and it’s boundaries.

When models can predict accurately whether it will rain in 3 days days time, we may have some hope, however I am confident that day will never come.

Ok.. Dr Svalgaard: How did you determine the initial value for the elevation? Did you use a set of ballistics tables that specified the distance and/or the gun size, or did you guys just guess on the initial distance or elevation? My suspicion is you used a set of tables to get the initial shot near the target and then fine tuned from there.

The initial elevation depends mostly on the observer who sees the target. His coordinates may only be approximate, so the first salvo will likely not hit the target. Based on the approximate coordinates the physics of firing of projectiles and of the influence of the air [wind, pressure, temperature] determine the initial elevation.

Dr. Svalgaard: Do you mean to tell me that you explicitly solved the following equation every time you made your initial shot? : (Rg/v^2) = sin 2θ I don’t think so. Even if the initial distance estimate was off You probably used a set of tables to determine this initial shot. And made an allowance for windage and air resistance. At some point someone had to sit down and calculate those tables. So you used a model that was validated and confirmed by empirical and experimental data. Climate models are neither confirmed or validated by empirical data. Ergo they are not to be trusted.

Of course, there were tables [back then] that were precalculated. Just like there were tables of sines and cosines. Nowadays there are no more tables, everything is calculated on the fly [even sines and cosines].

And you are wrong about the climate models: they HAVE been experimentally tested and found to be wrong. We have not yet figured out how to do it, so the second salvo for climate models overshoot. By the third slave we may get it right. It takes a long time to test, perhaps 15 years or so.

There is a fatal flaw in the utopist belief that super-smart computers will save us. This assumes they’ll be honest, but intelligence doesn’t guarantee honesty.

“This is why I am deeply skeptical, about claims that computer models created by people who already think they know the answer, who have strong preconceptions about the outcome they want to see, can accurately model the climate.”

In other words these are the hypothesis’ illustrated by a computer model.

How well this fits in with the video below.

If the results of the hypothesis don’t agree with observations then its WRONG – IT DOSN’T MAKE ANY DIFFERENCE HOW BEAUTIFUL YOUR GUESS IS, IT DOESN’T MATTER HOW SMART YOU ARE, OR WHAT THE PERSONS NAME IS – ITS WRONG!

Richard Feynman https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EYPapE-3FRw

Cheers

Roger

http://www.rogerfromnewzealand.wordpress.com

Richard Feynman was proven wrong in the case of the solar neutrino problem. The hypothesis [the solar model] priced a neutrino flux that did not agree with the observations, but the model was correct. The observations turned out to be wrong. Lesson: blanket statements should be avoided.

Well in this case, I think the observations are probably as close we are going to get to reality.

Cheers

Roger

Are you suggesting that all thermometers and satellite sensors are wrong? I have heard that some people are now advocating dropping the “empirical” from empirical science, but then we’d just be left with a dogma, and we know what happens to heretics.

We seem to remember that Newton had the same problem with the Astronomer Royal who produced some observations that demonstrated that Newton’s theories were wrong; Newton persuaded him that his observations were wrong.

That was an awful lot of scrolling down to reach the admission that climate models have it wrong.

The next logical step would be to see a description of how climate models could possibly have got it wrong. After all, thousands of people and millions of data points obviously went into the development of these models. And since they’re all created with the best of intentions and the best scientific theories, it’s unlikely that anyone could have made a mistake of any sort.

And clearly the concept of a preconceived expected outcome can’t have anything to do with it.

Here’s an idea: maybe one or more of the assumptions going into the models are wrong, and nobody wants to admit that.

Here’s another idea: There’s more things going on that effect reality than any of the modelers is aware of or accounted for. It’s hard for someone who prides himself on his knowledge and conclusions to admit that he doesn’t know after all.

There’s more going on in reality than meets the “01001001”. 😎

At the risk of repeating some of the large number of excellemt responses here the issue is simple.

Garbage in – Garbage Out … GIGO

Stocking a stores shelves, or designing a car, are ALL based on a strong understanding of the data points, processes and physics of what is attempting to be modeled.

We can design aircraft in a computer model because (a) aerodynamics is a relatively simple science and (b) we understand most everything about fluid dynamics and thus about aerodynamics.

The model for an aircraft is also well developed and can be tested by building a copy of the model output, and testing in a wind tunnel. If the modeled output – the aircraft – performs as expected in a wind tunnel we can then attempt to fly it … and thus we can fully test the models ability.

We have no clue about the vast complexities and interactions, let alone all the inputs and physics, of how our climate works. Add that climate is chaos based – unlike an aircraft wing – where the same wing profile will give you the same Lift and Drag numbers every time – there are no certainties in climate.

And even models employing areas where we have good understanding are not foolproof.

I have worked with modeling in Indycars. We can input all the parameters – track layouts (turn radius, banking etc), the aerodynamic numbers from wind tunnel testing of the car, suspension geometry, tire data, etc – and despite the physics of both the car mechanically driving the track and the aerodynamics of the car in free air being well understood – the models can often be completely wrong. Because even with two well understood processes when you put them together – and operate an aero car ON the track – an entirely new process and interactions can occur.

The best of “experts” can often be block headed and clueless as well.

Again involving open wheel Indy type cars … one year we had a top shock absorber company come onboard as a sponsor. They committed an entire staff of engineers determined to revolutionize how shocks affected operation (and speed) of the cars.

One issue with race cars are the sidewalls of the tires – they are an undamped spring – think of what happens when you push on a balloon and it springs back.

Without damping of a spring you have little control – you need to keep the tire on the ground and the “contact patch” where rubber meets the road – in place.

The rocket scientist types decided they were going to jack up the tire pressure to make tires as stiff as possible and then use sophisticated shocks to manage the tire bouncing over bumps.

They spent all winter with their computer models and running their design on the chassis dyno. The model and the chassis dyno – which simulates the cars performance on track – all showed this new idea was fantastic.

We went to the track and the car was horrible – dead slow – all over the race track – all but uncontrollable.

I and the driver knew the problem as we talked and looked at the telemetry. Simple, basic, “seat of the pants” knowledge and experience. When you make the tire hard as a brick; (1) you can never build any heat in the tire, and (2) without that heat, and with no sidewall deflection in the tire, you have no contact patch – the tire tread does not stay on the ground and grip the track.

At lunch the engineers made a tiny tweak trying to figure out something. The driver and I made a tweak too – we reduced tire pressure from 50lbs to a normal 28lbs without telling anyone.

The car was immediately fast again – because the lower pressure allowed the tire to build heat and the flex in sidewalls meant the tire now could grab and conform to the track .

The engineers thought they’d found the holy grail. Until we told them what we had done. That despite the nearly $1 million budget and all these high powered highly skilled engineers, they had forgotten the single, most basic part of race car engineering – the tire contact patch.

Without a good contact patch a car – any car – is all but undriveable. This is race car engineering 101. When you pump up your tires til they’re rock hard, even a street car becomes terrible to drive.

In the end we literally threw away everything they did. Bolted stock parts and standard shocks on the car and went and won races anyway – based on the drivers skill and the teams good, basic race car engineering.

Garbage in = garbage out.

When it comes to climate modeling almost everything is NOT well understood – garbage in. The experts say – but look – when we run past data thru the model the output matches the real world. Of course it does – that is EXACTLY the output the model was designed to provide.

It was designed to output a SPECIFIC result – not to output a modeled result. Which is why it is great at hind-casting and worthless for forecasting the future.

Garbage in = garbage out.

The failure of the scientific method – the massive hubris of the climate alarmists as their cause activism supercedes their scientific knowledge – where their fervent desire to support the cause, to prove the “consensus” overwhelms their scientific training.

In the old days you had to choose – scientist or activist, researcher of the truth, or advocate for a predetermined position. Today they claim they can be both – that the seriousness demands they be both scientist and cause advocate.

Which is a gross corruption of the scientific method – where everyone seeks the truth, not to prove a particular position.

A.Scott

Informative story. Thank you.

I know where you are coming from A . Scott . Another recent case of computer modelling on competition car performance was at Pikes Peak .

http://www.motorsport.com/hillclimb/news/s-bastien-loeb-and-the-peugeot-208-t16-pikes-peak-set-new-record/

But this was the actual competition departments own program & they took analysis from practice runs to work out the possible fastest time that the car could do up the hill .

And then Seb Loeb went faster than the computer said was possible .

One of the things that can vary all of the time is the amount of grip that a car can get .

Highest coefficient of friction will vary but will usually be beyond the point where a tyre starts to spin . So a fixed traction program , [ or even a variable program which has to be measured ] will never match a world class competition driver who sees the surface ahead & is constantly adjusting for it even before it has happened .

So yes , a top line computer program was outdone by the efforts of I man .

Exactly – you cannot “model” the human response ….A top Indycar (or other) driver can feel the tire – feel the contact patch. They can manage that contact patch with how they drive the car. They also can drive the car past the point of adhesion – when the slip angle has exceeded the grip avail. A very good driver can anticipate that lack of grip and what the car will do and where it will go when that occurs.

Climate is far more complex that modeling a race car or an airplane. And involves chaos – data that does not fit known conclusions.

Eric

More than anything, software is a mirror of the creator’s opinions

I think this is completely unfair – this would render a compiler useless for example, as according to this logic the compiler’s output is its programmer’s opinion rather than the binary instruction derived from the users code. It might be true if you’re creating say your own game where you’re in the creative domain and you’re creating a virtual world. But this isn’t the case in scientific/engineering software where you are commissioned to produce/design something that implements well established algorithms.

So I don’t agree with the premise of the post. There are many reason why climate models are crap and why the shouldn’t be trusted but that has more to do with bad implementation and poor assumptions, but that does not mean that “software is the mirror of the creators opinions”; instead it is more commonly the implementation of well established science whether that is done well or not is your opinion.

CD

Eric is exactly correct. Who’s opinion was used to created the syntax for the language? The author’s. Clearly you have never witnessed close at hand the construction of a computer language syntax. It is either a single author’s “opinion” or it is a committee like opinion.

Also, you are clearly confused when you state that creating a compiler is entirely different from creating “your own game”. A compiler is nothing more than a sophisticated game in your analogy. The language elements chosen for a particular compiler are simply those chosen by the author.

“Well established algorithms”. Hee hee. Have you read the emails from the programmer at the CRU.

And yes it does mean that “software is the mirror ofthe creator opinions”. Well established science? Who says? Your opinion?

Larry

A compiler is a type of software, a game is a type of software that’s about where the analogy ends. If the relationship were any closer then the compiler wouldn’t be much use.

The output of a compiler is not the opinion of the programmer, the rules on optimization, intermediate states are in the design which is in the hands of the programmer (that’s the processing step), but the output has to run on a particular CPU with its own number of registers, switch architecture etc which if the compiler is to even work then it’s out of his/her hands – the compiler’s programmer has to honour the hardware requirements. Furthermore, the output from a statement akin to 1+1 is not in the opinion of the compiler’s designer – if the compiler is to actually to function as a compiler. He/She could make the executed code do something crazy but then by even the most naive programmer that’d be considered a BUG in the compiler!

Have you read the emails from the programmer at the CRU

Firstly, I was talking in general sense. And as for climate models, they do use standard algorithms the main problem is that they can’t solve energy transfer and turbulence at the resolutions they need to due to limitations in computing power – but that doesn’t mean that they are expressing an opinion. The limitations of their implementation are expressed from the outside even on the NASA website. And that’s all you can do.

Well established science? Who says? Your opinion?

Nearly all of the achievements in space exploration are due to software expressing well established science such as Newtonian Physics. If the author were correct in his assertion these were just the result of good opinions. That is no my opinion. And remember the author was talking about software in a general sense.

The bottom line is that if natural weather and climate variability are responses to solar variability rather than being internal chaos, all the current models are ersatz.

Great point.

I like my brother’s lesson when I was just learning the trade, “A computer is inherently no more intelligent than a hammer.” I remember my advice to my Dad when he got his first business computer, “Don’t hit it, don’t throw it out the window. It’s only doing what you told it to.”

Back in the early 70’s, for a senior EE project, I worked with my adviser and some grad students on a model of Lk Michigan currents. At one point I asked him when would we go on the lake and see how well our model matched reality. After he stopped laughing, he explained that the sole purpose of a computer model was to almost match the expectations of whoever was paying for the grant, and then justify next years grant.

I have also come across government science as a big scam. It’s just a subset of government contracting. But here you falsify what everyone is saying here.

The problem is not science or computer models in general, it’s government involvement in science.

I worked for a while at NPR, and my preconceived notions changed a bit. I realized that the people were not naturally biased. They were just responding to the bias inherent in the situation. We could staff NPR with rabid libertarians, yet eventually, they would start shifting towards a pro-government view.

It’s the same with scientists. We need a complete separation of government and science.

As a professional software developer, I’ve been saying this for years. People have vast misconceptions about climate modeling software. The climate models are nothing more than hypotheses written in computer code. The models aren’t proofs. The models don’t output facts. The models don’t output data.

The models don’t output facts

If so, the discrepancy between the model output and the observed temperatures cannot be taken as proof that CAWG is wrong. For this to happen, the models must be correct, just badly calibrated. If the models just output garbage you can conclude nothing from the disagreement.

Is a forecast a fact, or a set of facts? Is a prediction a set of facts?

Sounds like the scientific method itself can’t be used for anything, Leif, since an hypothesis can’t be compared with observations, according to you.

Nonsense. It is well-established what the Scientific Method is.

You don’t have a clue about science if you think models output facts. I can make a computer program that outputs 5 when 2 is added to 2. Is that output a fact?

the discrepancy between the model output and the observed temperatures cannot be taken as proof

===========

it can be taken as proof that the models are wrong. your mention of CAWG is bait and switch.

Well, that’s not quite fairly stated. The observed discrepancy doesn’t prove that CAGW is wrong, it proves that the models are wrong. Obviously, given that the future hasn’t happened yet, the full range of possibilities must be given at least some weight, right down to the possibility that a gamma ray burst wipes us out in the next ten minutes. Sure, it is enormously unlikely, but when one is using Pascal’s Wager to formulate public policy, all one really needs is the words “wipes us out” in conjunction with “possibility” to fuel the political dance of smoke and mirrors. Indeed, it is quite possible that the models are wrong (in the sense that they cannot, in fact, solve the problem they are trying to solve and that the method they use in the attempt produces “solutions” that have a distinct uniform bias) but CAGW is correct anyway. Or, it is possible that we’re ready to start the next glacial episode in the current ice age. Or, it is possible that nothing really interesting is going to happen to the climate. Or, it is possible that we will experience gradual, non-catastrophic warming that fails to melt the Arctic or Antarctic or Greenland Ice Pack, causes sea level to continue to rise at pretty much the rate it has risen for the last 100 years, and that stimulates an absolute bonanza to the biosphere as plants grow 30 to 40% faster at 600 ppm CO_2 than they do at 300 ppm and weather patterns alter to produce longer, wetter, more benign growing seasons worldwide.

AGW could turn out to be anti-catastrophic, enormously beneficial. Thus far it has been enormously beneficial. Roughly a billion people will derive their daily bread from the increase in agricultural productivity that greenhouse experiments have proven are attendant on the increase of CO_2 from 300 to 400 ppm (one gets roughly 10 to 15% faster growth, smaller stoma, and improved drought tolerance per additional 100 ppm in greenhouse experiments). To the extent that winters have grown more benign, it has saved energy worldwide, increased growing seasons, and may be gradually reducing the probability of extreme/undesirable weather (as one expects, since bad weather is usually driven by temperature differences, which are minimized in a warming world).

So sure, the failure of the models doesn’t disprove CAGW. Only the future can do that — or not, because it could be true. The success of the models wouldn’t prove it, either. What we can say is that the probability that the models are correct is systematically reduced as they diverge from observation, or more specifically the probability that the particular prescription of solving a nonlinear chaotic N-S problem from arbitrary initial conditions, pumping CO_2, and generating a shotgun blast of slightly perturbed chaotic trajectories that one then claims, without the slightest theoretical justification, form a probability distribution from which the actual climate must be being drawn and hence can be used to make statistical statements about the future climate is as wrong as any statistical hypothesis subjected to, and failing, a hypothesis test can be said to be wrong.

The models can be, and are actively being, hoist on their own petard. If the actual climate comes out of the computational envelope containing 95% or more of their weight (one model at a time), that model fails a simple p-test. If one subjects the collection of models in CMIP5 to the more rigorous Bonferroni test, they fail collectively even worse, as they are not independent and every blind squirrel finds an acorn if one gives it enough chances.

rgb

just badly calibrated.

===============

calibration is a poor description of the process. the problem is that there is an infinite set of parameters that will deliver near identical back casting results, yet at most only 1 set is correct for forecasting. and there is no way to know in advance which set is the correct set. thus there is effectively 100% certainty that the exercise will result in meaningless curve fitting, not skillful forecasting, because you cannot separate the correct answer from the incorrect answers.

I’ve read every Leif comment on this thread, agree with all of them. I’ve rarely seen one person pwn a crowd to this extent. However, this one seems especially insightful.

Skeptics are simultaneously arguing that:

climatology is impossible AND they know AGW is false

climate models are impossible AND that CAGW is false

climate is chaotic and unpredictable AND that yet they can predict that CO2 will not cause an instability

That’s why my suggested approach is much better: get a clear description of the hypothesis, then scrutinize the underlying science and attempt to falsify with experimental & empirical evidence.

However, I think this has already happened. Steve M. pushed for a clear derivation of 3.7 W/m^2, and I don’t think any satisfactory response was ever provided. For example, the Judith Curry thread about the greenhouse basically admits that the original hypothesis as commonly stated was false. The latest formulation is weak enough that there is no longer any theoretical foundation for significant AGW.

While land surface data is lacking, there is enough of it to show no loss of night time cooling based on prior day’s increase, in fact it does just what would be expected, the last 30 or so warm years it’s cooled more, the prior 30 some years showed slightly more warming than cooling, but the overall average is slightly more cooling than warming. 30 of the last 34, 50 of the last 74 show more cooling than warming. This does require more precision that a single decimal point, if we restrict it to a single decimal point it shows 0.0F average change.

You just need to do more that average a temp anomaly.

…So what is real science in your esteemed opinion? Barycenter cycles? Piers Corbin? Monckton’s ‘simple’ model? Evans’ Notch Theory? ……

___________________________________________

here is what I would like to see.

1. data

The USAF in the 1950’s pushed spectrometer resolution to single line width. I would like to see that data and then take exactly the same data from today, and compare it, from ground level to 70,000 feet to see exactly how much the spectral absorption lines have broadened since the IGY. That gives me a quantitive and qualitative number upon which to do the calculations regarding increased absorptivity. I would also like to see exactly what altitude that the lines that are saturated, desaturate to see where the difference is. The predictions regarding stratospheric temperatures have been completely wrong, probably because this parameter is wrong.

2. More Data and explanation

I would like to see a rational explanation for the wide variation in Arctic ice between 1964 and 1966 and even into the 1973-76 period as has been shown from the satellite date. We make much of the change in the arctic since 1979, but we now know, from examining Nimbus data, that there was a LOT of variation before 1979 and particularly in the 1964-66-69 period.

That is a good start.

RE: The Singularity – my skepticism is not limited to “Killer AGW.” It’s getting harder and harder to improve actual computing performance. We’re at the point where we are confronting the underlying physics. You shrink the feature sizes any more and subatomic issues will rear their ugly heads. Chips are getting really expensive – hundreds or even thousands of dollars for a CPU. Some SSDs are now over 2 grand. Memory DIMMs as well. Expensive, increasingly unreliable, leaky electronics, running at too low of a voltage and the icing on the cake, most of the stuff now comes from China. I think a different sort of “singularity” may be looming and it is more in the category of the mother of all debacles.

They said the same thing in 1982 when we were making 2u CMOS, they expected to keep meeting Moore’s law, but didn’t have a clue how.

An iPhone 4S has better performance than the first generation Cray Supercomputer.

I just build a 4.0Ghz system for ~$500 that matches(or exceeds) the performance of the 3.3Ghz server I built 3 years ago for ~$5,000.

Every component is faster, has more capacity, and is cheaper.

Sure the latest generation of parts is pricy, but the price curve is steep.

And while the sub 35nm stuff might near the limit, quantum stuff is working it’s way through labs.

Actually, Moore’s law is dead. The idea of perpetual exponential growth is impossible in reality. I worked for a company that was involved with a project working on 450 mm wafers. It started out trying to target tin droplets with lasers, and ended up just shooting a laser into a tin atom mist caused by high pressure water on a block of tin.

450 mm / 30 nm technology has been delayed until 2018-2020, if not indefinitely.

I have a 22nm processor from Intel, and it looks like they are in the process of rolling out 14nm

http://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/silicon-innovations/intel-14nm-technology.html

So, Moore’s law isn’t dead yet, mostly likely we will actually find a limit with nanotubes, spin, or quantum devices, maybe 10 more years? But if you asked the device/process guys I worked with in 1982 they would have kely said the same 10 years.

Clever monkeys we are.

You should realize that Moore works at Intel, and so of course, Intel claims that Moore’s law is still active. It’s more like marketing hype. This more independent source talks about how it cannot continue in the physical world. Moore’s law has cost in it as well. The graph at the bottom shows that it has flattened out.

So my 10 year estimate was the same as Moore’s estimate.

But even at that it was 30 years ago they didn’t know how it would continue, yet it has. And as rgb said there’s other technologies being developed.

And one of the big issues is heat dissipation, air cooling starts getting hard over about 100Watt’s per sq in if I remember the unit correctly, Cray was using liquid cooling (iirc $200/gal Fluorinert sprayed right on the chip itself) to get to 200W/sq”. That’s why chip clock speed stagnated at 3 some Ghz for so long, too much heat to shed.

My development box is water cooled.

Depends on the cpu generation, most don’t really need it.

My new i7-4790K (88W) runs over 4Ghz , my server has dual E5-2643’s (130W) 128GB DDR3 it’s still air cooled.

I have no idea why you are asserting this. Moore’s Law has proven to have legs far beyond what anybody expected. We are very likely to be getting our next boost from new physics comparatively soon now (new in the sense that nanophysics is bearing unexploited fruit, not new as in new interactions). I just got a new laptop with a 500 GB SSD. That is so absurdly unlikely — my first personal computer was a 64K motherboard IBM PC, which I used to access an IBM 370 as a replacement for punching cards — that it isn’t even funny.

But even with Moore’s Law, to solve the climate problem at the Kolmogorov scale (where we might expect to actually get a fairly reliable answer) requires us to increase computational capability in all dimensions by thirty orders of magnitude. Even with a doubling time of (say) 2 years, at ten doublings per 10^3 that takes 100 doublings or 200 years. True, perhaps we will eventually work out a method that bears meaningful fruit at some intermediate scale, but the current ~100x100x1 km^3 cell size, non-adaptive, on a lat/long grid (the dumbest possible grid), with arbitrary initial conditions (since we cannot measure the initial conditions) and with only guesses for major parameters and mean field physics implemented on the grid isn’t even likely to work. It would be a miracle if it were working.

But if there was any real incentive to model the actual climate instead of a hypothetical future catastrophic climate, even now human ingenuity could probably have done better.

rgb

>> increase computational capability in all dimensions by thirty orders of magnitude

I think you’re assuming that climatology is an extension of meteorology. It’s not. The problem will likely be solved completely differently that you and others are imagining. I could list all the examples where it was not necessary to model reality at the molecular level, but it would be all of science, and you really should be smart enough to see that. However, only in the case of Climatology do people imagine that it’s going to require that.

State dependent simulations vs non-state dependent simulations, but that’s really the difference between detecting the pause in the simulator and not even bothering. Which is ultimately what they’re doing with modtran, a change on Co2 causes x warming, that’s really state dependent, it’s just very incomplete.

lsvalgaard, get kerbal space program, play with it, and notice the effect of changing the time step for the simulation, the bigger the time step the larger the deviations.

or “Universe sandbox” play about throwing planets around in orbits, try to reproduce each test with differing time rates (time delta between calcs).

Climate Simulations are presently way out partial due to time delta being way too large and grids way too large.

Any system that has feedback loops are very very sensitive to this and decay into chaos..

Obital calcs are trivial compared to climate feedback problems.

Obital calcs are trivial compared to climate feedback problems.

=============

agreed, yet even orbital mechanics are far from trivial. we still lack an efficient solution for the orbit of 3 or more bodies not in the same plane.

the current solution involves the sum of infinite series, which is not really practical unless you have infinite time.

And that is just 3 bodies interacting under a simple power law. And for all intents and purposes, no computer on earth can solve this.

So what happens? We approximate. We made something that looks like it behaves like the real thing, but it doesn’t. It is a knock off of reality. Good enough to fool the eye, but doesn’t perform when it counts.

Anyone who claims that an effectively infinitely large open-ended non-linear feedback-driven (where we don’t know all the feedbacks, and even the ones we do know, we are unsure of the signs of some critical ones) chaotic system – hence subject to inter alia extreme sensitivity to initial conditions – is capable of making meaningful predictions over any significant time period is either a charlatan or a computer salesman.

Ironically, the first person to point this out was Edward Lorenz – a climate scientist.

You can add as much computing power as you like, the result is purely to produce the wrong answer faster.

GIGO – Garbage In, Gospel Out.

Computers will allow you to get the wrong answer 100 times faster.

As one who did science-related computer modeling (when I worked for a living), I completely agree with the author’s points.

As a structural engineer who turned to the dark side of software “engineering” I will add one little observation to the many excellent ones which I have seen above (and I admit that I have not read them all)…

The worst nightmare for the programmer, tester and user is the subtle error leading to a result which meets all expectations… but which is woefully incorrect. For if the output is unexpected, then the design team will tear its hair out and burn the midnight oil to find the “problem” and beat it into submission. But if the numbers come out exactly as expected, then congratulations will flow up and down through the team and due diligence may soon fall on the sword of expediency.

Excerpt from The Art of Computer Programming by Donald E.

Knuth (4-6 ERRORS IN FLOATING POINT COMPUTATIONS).

All programming language mathematical libraries suffer from built-in

errors from truncation and rounding. These combine with errors in the

input data to produce inexact output.

If the result of a computation is fed back to the input to produce

“next year’s value” the collective error grows-rapidly if not

exponentially. After a few iterations, the output is noise.

collective error grows-rapidly if not exponentially.

=========

indeed that is the problem with iterative problems like climate. The error is multiplied by the error on each iteration, and thus grows exponentially.

for example, let each iteration be 99.99% correct. if your climate model has a resolution of 1 hour, which is extremely imprecise compared to reality, so 99.99% accuracy is highly unlikely, after 10 years there is 0.0002% chance your result is correct. (0.9999^(365*24*10))

1) You’re assuming all the errors are going just one way.

2) You’re assuming an unreasonable time resolution. Since the minimum time scale for climate is 10 years, why on earth would we need to have a time step of only one hour. Are climate factors such as solar input, ocean circulation and orbits changing on an hourly basis?

The atmosphere is only .01% of the thermodynamic system, so why would you suggest we spend so much effort on something that really can’t make much difference?

It seems like you want the problem to be too difficult to solve. It seems like you’re afraid of what the answer would show, like deep down, you believe AGW is true.

I believe AGW is false, and I welcome further advances in climatology, since I’m confident that it will eventually show that AGW from CO2 is impossible.

I’m wondering what the time step should be. We could use weather modeling as a guide. I think their time step is a minute. After 5 days, their accuracy falls off. 5 days / 1 minute = 7200 steps of accuracy.

If 1 day is like 10 years, then to get the next 5 climate states (5 decades), and if we assumed 7200 steps, the time step would be 60 hours.

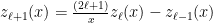

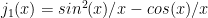

Y’all need to get a bit of a grip on your disrespectin’ of computer solutions of an iterative nature. For one thing, there is an abundance of coupled ODE solvers out there that are really remarkably precise and that can advance a stable solution a very long ways before accumulating significant error. For another, there are problems where the answer one gets after accumulating significant error may produce e.g. a phase error but not necessarily make the error at distant times structurally or locally incorrect. For a third, in many problems we have access to conserved quantities we can use to renormalize away parts of the error and hence avoid ever reaching true garbage.

and

and  of about the same order. That is, one subtracts two numbers with about the same number of significant figures to make a smaller number, over and over again because in the large

of about the same order. That is, one subtracts two numbers with about the same number of significant figures to make a smaller number, over and over again because in the large  limit the bessel functions get arbitrarily small for any fixed

limit the bessel functions get arbitrarily small for any fixed  .

. and

and  , one loses very close to one significant digit per iteration, so that by

, one loses very close to one significant digit per iteration, so that by  one has invented a fancy and expensive random number generator, at least if one deals with the impending underflow or renormalizes. Sadly, forward recursion is useless for generating spherical bessel functions.

one has invented a fancy and expensive random number generator, at least if one deals with the impending underflow or renormalizes. Sadly, forward recursion is useless for generating spherical bessel functions. ,

,  — which is laughably wrong — and apply the recursion relation above backwards to generate the

— which is laughably wrong — and apply the recursion relation above backwards to generate the  function all the way down to $\ell = 0$ and save the entire vector of results, one generates an ordered vector of numbers that have an increasingly precise representation of the ratio between successive bessel functions. If one then computes just

function all the way down to $\ell = 0$ and save the entire vector of results, one generates an ordered vector of numbers that have an increasingly precise representation of the ratio between successive bessel functions. If one then computes just  using the exact formula above and normalizes the entire vector with the result, all of the iterated values in the vector are spherical bessel functions to full numerical precision (out to maybe $\ell = 10$ to

using the exact formula above and normalizes the entire vector with the result, all of the iterated values in the vector are spherical bessel functions to full numerical precision (out to maybe $\ell = 10$ to  , at which point the error creeps back in until it matches the absurd starting condition).

, at which point the error creeps back in until it matches the absurd starting condition).

As somebody that routinely teaches undergrads to use built in ODE solvers and solve Newton’s Laws describing, for example, planetary motion to some tolerance, one can get remarkably good solutions that are stable and accurate for a very long time for simple orbital problems, and it is well within the computational capabilities of modern computers and physics to extend a very long time out even further than we ever get in an undergrad course by adding more stuff — at some point you make as large an error from neglected physics as you do from numerical error, as e.g. tidal forces or relativistic effects or orbital resonances kick in, and fixing this just makes the computation more complex but still doable.

That’s how we can do things like predict total eclipses of the sun a rather long time into the future and expect to see the prediction realized to very high accuracy. No, we cannot run the program backwards and determine exactly what the phase of the moon was on August 23, 11102034 BCE at five o’clock EST (or rather, we can get an answer but the answer might not be right). But that doesn’t mean the programs are useless or that physics in general is not reasonably computable. It just means you have to use some common sense when trying to solve hard problems and not make egregious claims for the accuracy of the solution.

There are also, of course, unstable, “stiff” sets of ODEs, which by definition have whole families of nearby solutions that diverge from one another, akin to what happens in at least one dimension in chaos. I’ve also spent many a charming hour working on solutions to stiff problems with suitable e.g. backwards solvers (or in the case of trying to identify an eigensolution, iterating successive unstable solutions that diverge first one way, then the other, to find as good an approximation as possible to a solution that decays exponentially a long range in between solutions that diverge up or down exponentially at long range).

One doesn’t have to go so far afield to find good examples of numerical divergences associated with finite precision numbers. My personal favorite is the numerical generation of spherical bessel functions from an exact recursion relation. If you look up the recursion relation (ooo, look, my own online book is the number two hit on the search string “recursion relation spherical bessel”:-)

you will note that it involves the subtraction of two successive bessel functions that are for most

Computers hate this. If one uses “real” (4 byte) floating point numbers, the significand has 23 or so bits of precision plus a sign bit. Practically speaking, this means that one has 7 or so significant digits, times an 8 bit exponent. For values of x of order unity, starting with

Does that mean computers are useless? No! It turns out that not only is backwards recursion stable, it creates the correct bessel function proportionalities out of nearly arbitrary starting data. That is, if you assume that

Forward recursion is stable for spherical Neummann functions (same recursion relation, different initial values).

Books on numerical analysis (available in abundance) walk you through all of this and help you pick algorithms that are stable, or that have controllable error wherever possible. One reason to have your serious numerical models coded by people who aren’t idiots is so that they know better than to try to just program everyday functions all by themselves. It isn’t obvious, for example, but even the algebraic forms for spherical bessel functions are unstable in the forward direction, so just evaluating them with trig functions and arithmetic can get you in trouble by costing you a digit or two of precision that you otherwise might assume that you had. Lots of functions, e.g. gamma functions, have good and bad, stable and unstable algorithms, sometimes unstable in particular regions of their arguments so one has to switch algorithms based on the arguments.

The “safe” thing to do is use a numerical library for most of these things, written by people that know what they are doing and hammered on and debugged by equally knowledgeable people. The Gnu Scientific Library, for example, is just such a collection, but there are others — IMSL, NAG, GSL CERNLIB — so many that wikipedia has its own page devoted to lists for different popular languages.

It is interesting to note that one of Macintyre and McKittrick’s original criticisms of Mann’s tree ring work was that he appeared to have written his own “custom” principle component analysis software to do the analysis. Back when I was a grad student, that might have been a reasonable thing for a physics person to do — I wrote my own routines for all of the first dozen or so numerical computations I did, largely because there were no free libraries and the commercial ones cost more than my salary, which is one way I know all of this (the hard way!). But when Mann published his work, R existed and had well-debugged PCA code built right in! There was literally no reason in the world to write a PCA program (at the risk of doing a really bad job) when one had an entire dedicated function framework written by real experts in statistics and programming both and debugged by being put to use in a vast range of problems and fixing it as needs be. Hence the result — code that was a “hockey stick selector” because his algorithm basically amplified noise into hockey sticks, where ordinary PCA produced results that were a whole lot less hockey stick shaped from the same data.

To conclude, numerical computation is an extremely valuable tool, one I’ve been using even longer than Eric (I wrote my first programs in 1973, and have written quite a few full-scale numerical applications to do physics and statistics computations in the decades in between). His and other assertions in the text above that experienced computational folk worry quite a bit about whether the results of a long computation are garbage are not only correct, they go way beyond just numerical instability.

The hardest bug I ever had to squash was a place where I summed over an angular momentum index m that could take on values of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4… all of which independently gave reasonable answers. I kept getting a reasonable answer that was wrong in the computation, fortunately in a place where I could check it, fortunately in a place where I was checking because at that point I wasn’t anybody’s fool and knew better than to think my code worked until I could prove it. Mostly. It turned out — after a couple of months of pulling my hair — that the error was that I had typed an n instead of an m into a single line of code. n was equal to zero — a perfectly reasonable, allowed value. It just gave me the wrong result.

I’ve looked at at least some of the general circulation model code. The code I looked at sucks. As far as I can see, it is almost impossible to debug. It is terribly organized. It looks like what it likely is — a bunch of code thrown together by generations of graduate students with little internal documentation, with no real quality control. Routines that do critical stuff come from multiple sources, with different licensing requirements so that even this “open” source code was only sorta-open. It was not build ready — just getting it to build on my system looked like it would take a week or two of hard work. Initialization was almost impossible to understand (understandably! nobody knows how to initialize a GCM!) Manipulating inputs, statically or dynamically, was impossible. Running it on a small scale (but adaptively) was impossible. Tracking down the internal physics was possible, barely, but enormously difficult (that was what I spent the most time on). The toplevel documentation wasn’t terrible, but it didn’t really help one with the code! No cross reference to functions!

This is one of many, many things that make me very cynical about GCMs. Perhaps there is one that is pristine, adaptive, open source, uses a sane (e.g. scalable icosahedral) grid, and so on. Perhaps there is one that comes with its own testing code so that the individual subroutines can be validated. Perhaps there is one that doesn’t require one to login to a site and provide your name and affiliation and more in order to be allowed to download the complete build ready sources.

If so, I haven’t found it yet. Doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist, of course. But CAM wasn’t it.

rgb

Thank you rgb, that was excellent. My experience has some overlap with yours. I didn’t starting coding until 1977. I agree 100% that numerical analysis is not impossible, like many on this site are implying. I started with Runge-Kutta around 1982 or so. These techniques have been around for about 115 years.

As a generator engineer, we used numerical methods extensively for analysis and design, including detailed electro magnetics, thermodynamics and stress analysis to enable weight reduction. Anyone who crosses a bridge or flies an airplane is trusting their life to the quality of this kind of work.

Some people are willing to express falsehoods in order to advance a political agenda. I am not one of those people.

Sadly, you are going exactly the wrong way in your reasoning, seriously. Suppose weather models used ten minutes as a time step instead of 1 minute (or more likely, less). Are you asserting that they would be accurate for longer then 5 days? If they used 100 minutes longer still?

You are exactly backwards. To be able to run longer, accurately, they have to use shorter timesteps and a smaller scale spatial grid (smaller cells) not larger and larger. The stepsize, BTW, is determined by the size of the spatial cells. Atmospheric causality propagates at (roughly) the speed of sound in air, which is (roughly) 1 km in 3 seconds. If one uses cells 100 km times 100 km (times 1 km high, for no particularly good reason) that is 300 seconds for sound to propagate across the cell, hence timesteps of 5 minutes. A timestep of 1 minute just means that they are using 20 km times 20 km cells, which means that their cells are actually on the high side of the average thunderstorm cell. To get better long term weather predictions, they would probably need to drop spatial resolution by another order of magnitude and use e.g. 2 km times 2 km or better yet 1 x 1 x 1 km^3. But that means one step in the computation advances it 3 seconds of real time. A day is 1440 seconds. A week is around 10,000 seconds (10080 if you care). That means that to predict a week in advance at high resolution, they have to advance the computation by around 3300 timesteps. But now the number of cells to be solved is 100×100 = 10000 times greater! So you might well take longer than a week to predict the weather a week ahead! Oops.

The spatiotemporal scale they use is a compromise (or optimization) between the number of cells, the time advanced per cell, the computational resources available to run the computation, and the need for adequate empirical accuracy in a computation that takes LESS than the real time being modelled to run. If they decrease the cell size (more cells), they can run fewer, shorter time steps in a constant computational budget and get better predictions for a shorter time. If they increase the cell size (fewer cells), they can run the computation for more, longer time steps and get worse predictions for a longer time. In both cases, there are strict empirical limits on how long in real world time the weather will “track” the starting point — longer for smaller cells, less time for larger cells.

The length scale required to actually track the nucleation and growth of defects in the system is known. It is called the Kolmogorov scale, and is around a couple or three millimeters — the size of micro-eddies in the air generated by secular energies, temperatures, wind velocities. Those eddies are the proverbial “butterfly wings” of the butterfly effect, and in principle is the point where the solutions to the coupled ODEs (PDEs) become smooth-ish, or smooth enough to be integrated far into the future. The problem is that to reach the future now requires stupendous numbers of timesteps (the time scale is now the time required for sound to cross 3 mm, call it 10 microseconds. To advance real time 1 second would require 100,000 steps, and the number of 3x3x3 mm cells of atmosphere alone (let alone the ocean) is a really scary one, lotsa lotsa digits. As I said, there isn’t enough compute power in the Earthly universe to do the computation (or just hold the data per cell) and won’t be in the indefinite future.

You also then have to deal very seriously with the digitization error, because you have so many timesteps to integrate over. It would require a phenomenal data precision to get out a week (10^5 x 10^4 = 10^9 timesteps, lots of chance to accumulate error). To get out 50 years, that would be around 2500 weeks, or 2.5 trillion timesteps integrating over all of the cells.

Climate models are basically nothing but the weather models, being run out past the week where they are actually accurate. It is assumed that while they accumulate enough error to deviate completely from the observed weather to where their “predictions” are essentially completely decorrelated from the actual weather, that in some sense their average is a representative of the average weather, or some kind of normative constraint around which the real weather oscillates. But there are problems.

One is that the climate models do not conserve energy. In any given timestep, the model “Earth” absorbs energy and loses energy. The difference is the energy change of the system, and is directly related to its average temperature. This energy change is the difference between two big numbers to make a smaller number, which is precisely where computers do badly, losing a significant digit in almost every operation. Even using methods that do better than this, there is steady “drift” away from energy balance, a cumulation of errors that left unchecked would grow without bound. And there’s the rub.

The energy has to change, in order for the planet to warm. No change is basically the same as no warming. But energy accumulates a drift that may or may not be random and symmetric (bias could depend on something as simple as the order of operations!). If they don’t renormalize the energy/temperature, the energy diverges and the computation fails. But how can they renormalize the energy/temperature correctly so that (for example) the system is not forced to be stationary and not basically force it in a question-begging direction?

Another is that there is no good theoretical reason to think that the climate is bound to the (arbitrarily) normalized average of many independent runs of the a weather model, or even that the real climate trajectory is somehow constrained to be inside the envelope of simulated trajectories, with or without a bias. Indeed, we have great reason to think otherwise.

Suppose you are just solving the differential equations for a simple planetary orbit. Let’s imagine that you are using terrible methodology — a 1 step Euler method with a really big timestep. Then you will proceed from any initial condition to trace out an orbit, but the orbit will not conserve energy (real orbits do) or angular momentum (real orbits do). The orbit will spiral in, or out, and not form a closed ellipse (real orbits would, for a wide range of initial conditions). It is entirely plausible that the 1 step Euler method will always spiral out, not in, or vice versa, for any set of initial conditions (I could write this in a few minutes in e.g. Octave or Matlab, and tell you a few minutes later, although the answer could depend on the specific stepsize).

The real trajectory is a simple ellipse. A 4-5 order Runge-Kutta ODE solution with adaptive stepsize and an aggressive tolerance would integrate the ellipse, accurately for thousands if not tens of thousands of orbits, and would very nearly conserve energy and angular momentum, but even it would drift (this I have tested). A one step Euler with a large stepsize will absolutely never lead to a trajectory that in any possible sense could be said to resemble the actual trajectory. If you renormalize it in each timestep to have the same energy and the same angular momentum, you will still end up with a trajectory that bears little resemblance to the real trajectory (it won’t be an ellipse, for example). There is no good reason to think that it will even sensibly bound the real trajectory, or resemble it “on average”.

This is for a simple problem that isn’t even chaotic. The ODEs are well behaved and have an analytic solution that is a simple conic section. Using a bad method to advance the solution with an absurdly large stepsize relative to the size of secular spatial changes simply leads to almost instant divergences due to accumulating error. Using a really good method just (substantially) increases the time before the trajectory starts to drift unrecognizably from the actual trajectory, and may or may not be actually divergent or systematically biased. Using a good method plus renormalization can stretch out the time or avoid the any long run divergence, but also requires a prior knowledge of the the constant energy and angular momentum one has to renormalize to. Lacking this knowledge, how can one force the integrated solution to conserve energy? For a problem where the dynamics does not conserve energy (because that is the point, is it not, of global warming as a hypothesis) how do you know what energy to renormalize to?

For a gravitational orbit with a constant energy, that is no problem. Or maybe a medium sized problem, since one has to also conserve angular momentum and that is a second simultaneous constraint and requires some choices as to how you manage it (it isn’t clear that the renormalization is unique!).

For climate science? The stepsizes are worse than the equivalent of 1-step Euler with a largish stepsize in gravitational orbits. The spatial resolution is absurd with cells far larger than well-known secular energy transport processes such as everyday thunderstorms. The energy change per cell isn’t particularly close to being balanced and has to be actively renormalized after each step, which requires a decision as to how to renormalize it, since the cumulative imbalance is supposed to (ultimately) be the fraction of a watt/m^2 the Earth is slowly cumulating in e.g. the ocean and atmosphere as an increased mean temperature, but some unknown fraction of that is numerical error. If one enforced true detailed balance per timestep, the Earth would not warm. If one does not, one cannot resolve cumulative numerical error from actual warming, especially when the former could be systematic.

All of this causes me to think that climate models are very, very unlikely to work. Because increasing spatiotemporal resolution provides many more steps over which to cumulate error in order to reach some future time, this could even be a problem where approaching a true solution is fundamentally asymptotic and not convergent, so that running it for some fixed time into the future reaches a minimum distance from the true solution and then gets worse for decreasing cell size (for a fixed floating point resolution). They aren’t “expected” to work well until one reaches a truly inaccessible spatiotemporal scale. This doesn’t mean that they can’t work, or that a sufficiently careful or clever implementation at some accessible spatiotemporal scale will not work in the sense of having positive predictive value, but the ordinary assumption would be that this remains very much to be empirically demonstrated and should never, ever be assumed to be the case because it is unlikely, not likely, to be true!

It is, in fact, much more unlikely than a 1 step Euler solution to the gravitational trajectory is a good approximation of the actual trajectory, especially with a far, far too large stepsize, with or without some sort of renormalization. And that isn’t likely at all. In fact, as far as I know it is simply false.

rgb

>> Are you asserting that they would be accurate for longer then 5 days? If they used 100 minutes longer still?

Wow, rgb, you wrote way too much. Especially since your assumption at the very beginning is wrong.

I’m absolutely NOT asserting that. The premise that has led you to put these words into my mouth seems to be that you can’t imagine that a climate model would not be just a simple-minded extension of a weather model.

I’m asserting that a proper climate model would be completely different than a weather model. If (or when) I were to create a climate model, I would focus on factors such as solar variation, solar system orbital variations, ocean circulation, tilt variations, geophysics, etc.

The climate is not significantly affected by the atmosphere, which is only .01% of the thermal mass of land/sea/air system. I would model the main mechanisms of heat transfer, but otherwise, there would be no reason to go any further. This is the way engineering is normally done.

My point was that the weather model might give us a clue how many iteration steps we can go before significant error creeps in.