Can you keep an open mind on the cause of winds? Climate science needs your help!

by Anastassia Makarieva

Many of us who have become researchers have been attracted by the dynamic and constructive debate that lies at the heart of scientific progress. Every theory is provisional waiting to be improved or replaced by a more thorough understanding. In this perspective new ideas are the life-blood of progress and are welcomed and examined eagerly by all concerned. That’s what we believed and were inspired by. Is climate science a dynamic field of research that welcomes new ideas? We hope so – though our faith is currently being tested.

Five months have not been enough to find two representatives of the climate science community who would be willing to act as referees and publicly evaluate a new theory of winds. Of the ten experts requested to act as referees only one accepted. This slow and uncertain progress has caused the Editors to become concerned: recently they “indefinitely extended” the public discussion of the submitted manuscript. The review process is perhaps becoming the story.

Here the authors share their views and request help.

Background

On August 06 2010 our paper “Where do winds come from? A new theory on how water vapor condensation influences atmospheric pressure and dynamics” was submitted to the Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Discussions (ACPD) journal of the European Geosciences Union. There we proposed a new mechanism for wind generation based on pressure gradients produced by the condensation of water vapor. ACPD ensures transparency during the review procedure: the submitted manuscripts and subsequent reviews are published online and available for public discussion. Authors can follow their submission through the process: they see when the Editor invites referees and whether they accept or decline.

Here are the standings as of 20 January 2011:

The Editor handling our paper has invited ten referees so far. Only one, Dr. Judith Curry, accepted. After 10 November 2010, in the record there have been no further attempts to find referees.

Normally ACPD’s discussion should take eight weeks. But in early January 2011, after twelve weeks in process, the status of the discussion of our manuscript was changed to “indefinitely extended”. In a recent letter to the authors, the Editor-in-Chief admitted that handling ‘a controversial paper’ is not easy, but assured us that the Journal is doing their best.

Discussion of our propositions secured over a thousand comments in the blogosphere within four weeks of publication indicating wide interest. Among the ACPD discussion participants two are active bloggers. Does blog culture outcompete formal peer review in evaluating novel concepts? It’s an open question. But let’s take a moment to focus on science.

Why condensation-induced dynamics is important

It would be generally useful to understand why the winds blow. It is sufficient to note that understanding the physical bases of atmospheric circulation is key for determining the climate sensitivity to changes in the amounts of atmospheric greenhouse substances, which is currently a highly controversial topic. The lack of current understanding may not be widely recognized outside the climate and meteorological community. But within the community moist processes in the atmosphere are admitted to be among the least understood and associated with greatest challenges. Not only theorists, but also modelers recognize their existence. For example, in a paper titled “The real holes in climate science” Schiermeier (2010) identified the inability to adequately explain precipitation patterns as one of such holes. In particular,

“a main weakness of the[ir] models is their limited ability to simulate vertical air movement, such as convection in the tropics that lifts humid air into the atmosphere.”

Any meteorological textbook will provide a discussion of buoyancy-based convection: how a warm air parcel ascends being lighter than the surrounding air. The convective instability of moist saturated air, so far neglected by the meteorological theory, is different. Any upward displacement of a saturated air volume, even a random fluctuation, leads to cooling. This causes the water vapour to condense. Condensation diminishes the total amount of gas and thus disrupts the hydrostatic distribution of moist air (if a hydrostatic equilibrium exists it is unstable to any such minor movements). The conclusion: moist saturated atmosphere in the gravitational field cannot be static.

Our analyses show that the current understanding of air movements being dominated by temperature and buoyancy is incomplete and flawed. Rather we find that the phase changes of water (condensation and evaporation) can play a much larger role than has previously been recognized. You can find out more if you see our paper. We would hope that a dynamic and advancing science would welcome new ideas.

Can the blogosphere help?

Perhaps we can help the Journal review our paper with your help. Are you an open minded climate scientist who would be ready and competent to discuss our ideas?

The ACP Chief-Executive Editor Dr. Ulrich Pöschl is aware that we are inviting your helps and asked that the following issues be noted (we quote):

1) ACPD is not a blog but a scientific discussion forum for the exchange of substantial scientific comments by scientific experts.

2) The open call for scientific experts who would be ready to act as potential referees would be a private initiative of the manuscript authors.

3) The list of potential referees compiled by the authors will be treated like the suggestions for potential referees regularly requested. The responsibility and authority for selecting and appointing referees rests exclusively with the editor.

If you have no conflict of interests and are willing to review our paper please contact the corresponding author (A. Makarieva) and we will forward your details to the Editor as a potential referee. For those who would like to remain anonymous please approach the ACP Chief-Executive Editor directly. We would be very grateful for your help – we have faith in you.

Anastassia Makarieva

on behalf of the authors:

A.M. Makarieva, V.G. Gorshkov, D. Sheil, A.D. Nobre, B.-L. Li

P.S. Thanks to Jeff for hosting our appeal on this blog. For a list of publications relevant to condensation-induced dynamics, please, see here.

Anastassia, does the system I described above elucidate a mechanism for the forces involved in tornadoes/hurricanes that you state are not accounted for in the current meteorological equations? When I asked “does it just not happen that way” I was not being facetious. I don’t know how the atmospheric dynamics play out. For mass to increase in the volume while maintaining hydrostatic equilibrium, I can imagine the dynamics but they are very tricky.

At condensation the water vapor itself loses vapor pressure, so there is a negative pressure coupled with latent heat. Is that negative pressure likely to pull in air from the same horizontal level? Is the air at that horizontal level likely to be at or near the same dew point at which condensation just occurred? In that case, the negative pressure of condensation can indeed pull in more air that condenses in the same volume, increasing the mass of that atmospheric column.

Coupled with the release of latent heat, you can get a growing mass of water condensate that remains in hydrostatic equilibrium if the energy of it’s own latent heat is increasing the vapor pressure from below and decreasing the vapor pressure from above. There is a large build up of pressure potential with the mass of water acting as a barrier in between. Take the water out of the way and you will experience a sudden large negative pressure at the surface. The atmosphere below is REALLY going to want to push through that cloud. It will eventually either: punch a hole through, spread out horizontally and seep up around the edges, or transfer its heat to the cloud by contact.

If a hole is punched, condensate will fall adjacent to warm, rising air. The condensate can then pick up the energy needed to vaporize again, allowing it to join the rising warm air. Depending on the scale of your suspended cloud layer and the size of the whole punched through it, I can imagine how this dynamic could create either a hurricane or a tornado.

Anastassia, just a thought, was reading your and Steve’s comments. I see a little of Dr. Pielke’s point of equal pressure viewpoint but pressure has only to do with the force/area and, with a static gravitational field at various altitudes, a constant weight/area whether a volume of water vapor is in a gas phase or a liquid phase. That view point does have to do with a static horizontal distribution.

However, the *density* (mass/volume) can change due to volume changes even though the pressure stays constant, vertically. That depends a lot on what scale you are speaking of. Air mass can only change over large areas so fast depending on the velocity of the winds. You might give a little deep thought on the density side. That is along the same lines of some prior investigations I was personally performing (just being curious) having to do with Venus’s atmosphere and lapse rate. Don’t leave density out of your considerations. Pressure is only on side of it. Both play into the dance in the sky so to speak. Mass on one side and volume on the other.

This is probably already well thought out but, just in case it wasn’t, I just had to raise that aspect.

Steve

February 2, 2011 at 5:09 pm

Thank you for your further comments.

You ask my view. Statements (1), (4) and (5) are correct. Statements (2) and (3) are not.

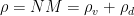

(1)

(1) is total air pressure (vapor plus dry air),

is total air pressure (vapor plus dry air),  is total air density.

is total air density.

, (2)

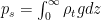

, (2) is the total amount of matter, including liquid, per unit volume. From this equation one concludes that surface pressure

is the total amount of matter, including liquid, per unit volume. From this equation one concludes that surface pressure  remains unchanged until the total mass of the column changes.

remains unchanged until the total mass of the column changes. at an arbitrary height we have from (2)

at an arbitrary height we have from (2)

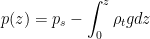

(3)

(3) . It satisfies both (1) and (2). Then we took an air volume at some height

. It satisfies both (1) and (2). Then we took an air volume at some height  and replaced it with an air volume with the same total density

and replaced it with an air volume with the same total density  but containing liquid instead of vapor. That is to say, we first had

but containing liquid instead of vapor. That is to say, we first had  and then

and then  , with

, with  and

and  kept constant.

kept constant. has not changed either. Dr. Gavin Schmidt referred to this as “condensation *per se* has no effect on air pressure”.

has not changed either. Dr. Gavin Schmidt referred to this as “condensation *per se* has no effect on air pressure”. has dropped by the amount of partial pressure

has dropped by the amount of partial pressure  of vapor:

of vapor:  .

. . ) But it is not the other way round! The amount of liquid that suddenly appears in the atmospheric column has nothing to say about whether the hydrostatic equilibrium is maintained or not.

. ) But it is not the other way round! The amount of liquid that suddenly appears in the atmospheric column has nothing to say about whether the hydrostatic equilibrium is maintained or not.

The idea that nothing happens until the mass of condensate is removed represents a fundamental physical misunderstanding of the nature of hydrostatic equilibrium. This misunderstanding is spread widely, as illustrated, for example, by the quoted comment of Prof. Pielke above and earlier of Dr. Gavin Schmidt. The error is visualized with utmost transparency in the work of Bryan and Fritsch (2002) (see our critique here, p. C12011), where a static (motionless) atmosphere in equilibrium accomodates liquid droplets that neglect gravity by hanging around everywhere throughout the atmospheric column, while the air pressure is strongly non-hydrostatic (due to the rapid decline of vapor pressure with height).

The correct equation for hydrostatic equilibrium is

where

This fundamental equation is replaced in meteorology by the following one:

where

For pressure

Now let us see how (2) violates the ideal gas law. Suppose initially we had a static equilibrium atmosphere with no liquid,

Since neither the total amount of matter in the column nor total density distribution has been changed by such a procedure, from the modified “hydrostatic equilibrium” (2) and Eq. (3) we would have to conclude that pressure

But the ideal gas law teaches us that pressure (which is, by the way, a scalar) is proportional to the total number of particles per unit volume. By replacing vapor by liquid we have reduced the amount of particles by the number equal to the number of vapor molecules. In the result, pressure at

To summarize: liquid does not make a contribution to the ideal gas pressure, in contrast to what Eq. (2) supposes.

Immediately upon replacement of vapor by liquid, pressure has dropped and a non-equilibrium pressure gradient force appeared. By formulation, this force will be (and have been) ignored in all models where hydrostatic equilibrium is incorrectly represented by Eq. (2).

The deviation of the observed pressure distribution from (1) can tell us how much liquid falling at terminal velocity the upwelling flow could possibly sustain in the atmosphere. (Direct observations show, btw, that this amount is very minor,

Thanks Anastassia, you’ve given me a lot to chew on.

The meteorological terminology has been particularly confusing to me in respect to “water vapor” and “dry air”. Water condensate and water vapor are used interchangeably – but suspended water droplets, such as a mist, are not water vapor! (a mist is a colloid) Air is considered “dry air” until the dewpoint is reached, despite the fact that it could be nearly saturated with water molecules (a.k.a. water vapor). In meteorology, water vapor laden air is “dry air” and a mist of water is “water vapor”.

wayne

February 2, 2011 at 8:02 pm

Thank you for your further comments. One of our points is that the Archimedes force associated with buoyancy is minor in comparison with the condensational pressure gradient force associated with vapor removal from the gas phase.

Kevan provided several useful calculations which can be viewed as epitomising the concerns of Prof. Pielke and some other scientists about the “much larger effects of latent heat.” Let me overview them here once again.

The release of latent heat diminishes the rate at which temperature drops with height when the air ascends adiabatically. The moist adiabatic lapse rate depends on the amount of vapor and grows as the vapor is depleted: from about 4 K/km at the surface at T = 20 C. The dry adiabatic lapse rate is 9.8 K/km (you can see these lapse rate profiles in Fig. 2e here). At 10 km the cumulative temperature difference between the moist adiabatic and dry adiabatic columns amounts to about 30 K, or 10% of absolute temperature T ~ 300 K.

At one and the same pressure the air that is warmer by 10% will have approx. 10% lower density rho’ = pM/R(1.1T) than air at temperature T with rho = pM/RT . This estimates the net effect of buoyancy as (rho’ – rho)g as 0.1 rho g. This gives us 1 N/m^3 if we take rho = 1 kg/m^3 (in reality rho is lower at 10 km, but we neglect this). Kevan correctly estimated (see also my reply) that even complete removal of vapor by 10 km will make a minor correction to this estimate. (To which direction — depends on how you define the atmospheric columns that you are comparing. One can argue that removal of vapor with Mv = 18 g/mol makes the air heavier (reduces buoyancy) by increasing its molar mass M ~ 29 g/mol. Alternatively, one could conclude (as Kevan originally did, if I got him right) that vapor removal increases buoyancy by decreasing pressure p. But in either case the effect is minor due to the small ratio pv/p ~ 0.01.)

It is at this point where some people would stop having concluded that the condensational vapor sink is unimportant for atmospheric dynamics.

In our paper we are presenting a different force, not calculating a contribution of the vapor sink to buoyancy. This condensational pressure gradient force is estimated as dpv/dz = pv/hv ~ 1 N/m^3 in the lower atmosphere (pv ~ 2×10^3 Pa, hv = 2 km). As one can see, thus estimated, the two forces — buoyancy and condensational — are of comparable magnitude, 1 N/m^3. (This is another interpretation of the result shown in Fig. 1c of our paper, where the maximum pressure differences above and below zc are approximately the same).

But the buoyancy effect estimate is a gross overestimate. In reality 30 K temperature differences are practically never observed between the areas of ascent and descent. Horizontal mixing destroys this theoretical temperature difference, making the lapse rate close to the average value of 6.5 K/km everywhere. Moreover, the dry adiabatic descent increases surface temperature in the region of descent, further diminishing the theoretically possible temperature and density difference. There is also the problem of surface to volume ratio (a small warm balloon and a several hundred or thousand kilometers’ wide warm atmospheric volume will differently react to buoyancy differences).

In our paper we do not estimate the buoyancy effects (enormous work has been done on that). We show that the condensational pressure gradient force alone is sufficient to explain the observed circulation intensity on a variety of spatial scales. This is an independent argument that, in the same context, the buoyancy effects (whether due to latent heat release or differential heating) are minor in comparison. The continued neglect of the condensational pressure gradient force is scientifically unjustified.

Note that both the buoyancy-related (rho’-rho)g and the condensational pressure gradient pv/hv forces are vertical forces. Under the independent condition that the atmosphere is close to hydrostatic equilibrium, the action of both forces is manifested via formation of horizontal pressure gradients, like the one we estimate in Eq. 37 of our paper.

Note also the different spatial localization of the forces: as calculated above, the buoyancy related force depends on height and grows with increasing temperature difference caused by latent heat release. The condensational pressure gradient force, in contrast, dominates in the lower several kilometers of the atmosphere, i.e. where most weather phenomena that affect our life occur. The condensational pressure gradient force tends to zero in the upper drier atmosphere due to the decrease of pv.

Steve

February 3, 2011 at 4:51 pm

There is some confusion between daily life and meteorological terminology. By “dry air” in meteorology it is common to understand everything except H2O. That is, if you have moist air with pressure p, its pressure is a sum of partial pressures of “dry air” pd and vapor pv, p = pd + pv.

It is true, however, that sometimes in meteorology one speaks of “airborne moisture” thus treating both small droplets and vapor as a single constituent. In daily life, at least in Russia, by “vapor” people understand the small clouds that apppear, for example, when you breathe outdoors on a frosty day, or above a boiling kettle. This is, of course, incorrect.

Anastassia,

I can’t tell you how much I have enjoyed this conversation. You have really open my eyes to some very important aspects of water vapor. So I don’t overstay the welcome I’ll just add a few things that might let you know where I was coming from and a pointer that might make it easier for you to press your point while trying to get others to see deeply into your paper, but quickly.

I almost feel a bit of boyish guilty of hijacking this topic and dragging it into talking of single clouds while all of the time I did realize that your paper is speaking on a much, much larger scale, cloud/vapor systems at the global scale. Here’s why: I spent so many hours years ago in a sailplane trying to understand clouds. I was failing miserably. The manuals told of heat, thermals, condensation and what on the ground you were to look for to lead you to these invisible thermals. Of course it is heat, look for dark plowed fields below, large black parking lots, etc that is where you will find lift. It also pointed out to stay away from water, forests, and most anything green for that was always where the sink would be for these were always cooler.

Well, as it turned out that simple explanation in the manual was wrong about half of the time. A large lake with green around the edge usually, if there was a slight breeze, would have great thermals with clouds always on the leeward side and that made absolutely no since at the time. Here was two cool surfaces with great lift and the dry, dark plowed fields closer to the airport had terrible sink, we were then in a drought and it was bone dry. I was lost, moisture never crossed my mind. To the library for meteorology books. They said basically the same, it’s all in the heat.

I guess you see my absolute glee in your paper. You have answered a question I have pondered on for some twenty five years. I kick myself now, of course, it’s the condensation, dummy! See, I was trusting the authorities, the manual and meteorological books as the information source without ever questioning it. What enlightenment. Even though that sailplane experience only lasted for a few years and that was long ago I think I’ll pass this information on to some soaring clubs and maybe Schweizer sailplane manufacture to have them pass it along to any newbies. Every pilot when soaring should know this effect.

So much for that.

Now, on your paper, it was a tiny mention of someone above that mentioned that water vapor takes up 1000 times more volume that water. That is all it took to get my attention !! Otherwise, I might have skipped right by this whole post. Meteorology always interests me but seeing deep math sometimes I think, don’t have time right now and go on, super glad I didn’t.

I calculated that 1000x volume and came up with a much larger value, I hope I did it correct, some 23500 times the volume, water to water vapor. Really either if these values are big enough to work in letting anyone visualize immediately this huge differences involved, for without that mental view, it seems many just pass it something like this: it’s a big atmosphere so surely some water vapor is not going to make that much difference. Next time it rains 4 inches over this state I will know it is equal to some one and a half vertical miles of the atmosphere that just fell. Anyone with the least bit of imagination knows immediately that this results in huge horizontal pressure differences.

I wish all science papers were required to have a “plain English” lead in so a mental view could be formed before the heavy math came into play, but that’s just the way my mind works. Guess I’m suggesting that you might consider getting it visual up front. Sometimes pure equations can hide the huge scale until you get your mind deep into them and start applying some actual numbers. Just a thought.

Wish I could be more help but my sidetrack into planetary atmosphere physics (climate science ☺) started but a little over a year ago. My last thirty years of interest in physics has always been more in other areas, particle physics, astrophysics, gravity, etc.

wayne;

fascinating commentary. Thank you. But I don’t know where either of the figures come from! (1000, 23,500). What pressure, what temperature, what atmosphere?

Starting with a vacuum, one could “fill” the space with any amount of vapor desired. The conditions on Mars, e.g., are right at a “triple point” combination, where H2O can switch between vapor, liquid, solid with minute changes of conditions. In Earth’s air, there are various saturation points you could pick.

Having been ‘out of circulation’ in January I have only just found this. I am amazed how much I can understand of the discussion paper at first read and I fully intend to work my way though it and read all the comments again, in more detail. I had been aware of previous material at the Air Vent but not really engaged with it.

As wayne says 2 comments above:

“Meteorology always interests me but seeing deep math sometimes I think, don’t have time right now and go on,..”

However, I find the discussion paper quite accessable, so I just wanted to say thank you to Dr Makarieva, for such a clear exposition.

Also, Chris Reeve‘s comment above:

“…. the van der waals force — works on the microscopic scale. […] ” “This is also the principle force which creates the sometimes-elaborate structures we see solids form into — like crystals and snowflakes.”

Biology knows this well and exploits proteins to enable condensation / crystallisation reactions that chemistry tells us should not otherwise happen (under the gross conditions) – for example ice nucleating bacteria and carbonate shell formation.

Brian H says:

February 11, 2011 at 7:48 am

wayne;

fascinating commentary. Thank you. But I don’t know where either of the figures come from! (1000, 23,500). What pressure, what temperature, what atmosphere? ….

===============

Hi Bryan.

Thanks, but I do see a mistake in my thought.

Initially taken from an example from engineeringtoolbox site:

The specific humidity for saturated humid air at 20 ºC with water vapor partial pressure 2333 Pa at atmospheric pressure of 101325 Pa (1013 mbar, 760 mmHg) can be calculated as:

x = 0.62198 (2333 Pa) / ((101325 Pa) – (2333 Pa)) = 14.7 g water/kg air.

So how many times does that 14.7 g of water fit into one cubic meter of water, 55396 times. But one kg of air is not exactly one cubic meter so corrected for 1.23 kg/m3 of air = ~45000. Can’t find my original calculations but it was very similar to that. Can’t seem to reproduce the 23,500 figure.

But that is getting an answer to a wrong question, that is, how many cubic meters of air does it take to hold one cubic meter of water at that partial pressure when in vapor form, so step back to the 1000 figure which dscott used above because that is roughly the ratio of the densities. Whoops. But still even ~1000 times the volume leaves a certain visual impression that conflicts the thought that condensation effects are so small they can be totally ignored. That was my main point.