Guest Post by Willis Eschenbach

This is a two-part post. The first part is to correct an oversight in my recent post entitled Rainergy.

The second part is to use that new information to analyze the effect of clouds on the El Nino region.

So, to the first part. In my post Rainergy, I noted that it takes ~ 80 watts per square meter (W/m2) over a year to evaporate a cubic meter of seawater. Thus, the evaporation that creates the ~1 meter of annual rain cools the surface by – 80 W/m2.

Then the other day I thought “Dang! I forgot virga!”

Virga is rain that falls from a cloud but evaporates completely before it hits the ground.

Figure 1. Virga diagram

Here’s the thing. When the virga evaporates, it’s just like evaporation from the surface. It cools both the raindrops and the surrounding air.

That’s what leads to the cold storm winds entrained by the rain that hit the ground vertically and spread out around the base of the storm. You can see all of that happening in this amazing time-lapse video, with the vertical entrained wind striking the surface, spreading out across the lake, and finally agitating the trees in the foreground. On the left of the video you can also see virga falling and evaporating before it hits the ground.

And it’s not just the virga. The raindrops are all evaporating as they fall, which is why rain is almost always so cold.

So I set out to see how much rain evaporates completely before hitting the ground. I couldn’t find a whole lot on the subject, but a few papers said 50% to 85% of the rain evaporates. See e.g. Sub-cloud Rain Evaporation in the North Atlantic Ocean which says 65%

This makes sense, because the huge surface area of the hundreds of thousands of tiny droplets of water allows for large amounts of evaporation.

And here’s the reason why all of this is important. I had estimated the evaporative cooling associated with a meter of rain to be -80W/m2 per year. That’s the energy it takes to evaporate that meter of seawater.

But I had overlooked the additional cooling from the evaporation of the rain itself. Given that something on the order of half of the rain evaporates, it would provide an additional 40W/m2 of cooling. And more to the point, it’s not included in the rainfall data—it can’t be, it has evaporated.

Now as I said, there are not a lot of studies, and the evaporation rate depends on a host of variables. So what I’ve done is take the estimate that not half, but a quarter of the rain evaporates before hitting the ground. That gives a conservative value for the evaporative cooling of the rain before hitting the ground, although it is likely higher.

This gives a revised estimate of the evaporative cooling associated with a meter of rain as not -80 W/m2 for a year per meter of rain as I’d thought, but -100 W/m2 per meter of rain.

Thus endeth Part The First.

With my new estimate of the relationship between rainfall and evaporative cooling, and mulling over some ideas of Ramanathan, I decided to look at the variations in total cloud cooling of the sea surface in the area of the El Nino/La Nina phenomenon. To start with, blue box below shows the location of what’s called the “NINO34” area—5°N to 5°S, and 170°W to 120°W. The sea surface temperature in this area indicates the state of the Nino/Nina alteration.

Figure 2. Average surface temperatures and the location of the NINO34 area. Average from Mar 2000 to Feb 2023

And here is the temperature of the NINO34 area over the CERES satellite period. Note that the phenomenon is known as “El Nino”, a reference to the Christ child, because it peaks around December or November. And when there is a full Nino/Nina alteration, it hits the bottom around December/November one year later (blue areas). I discuss this further in my post “The La Nina Pump“.

Figure 3. Monthly sea surface temperatures in the NINO34 area. Note the large swings from ~25°C to 30°C, which make this area valuable for investigating the relationships between sea surface temperature (SST) and various cloud parameters.

Now, those familiar with my work know that my theory is that clouds act as a strong thermoregulator of the surface temperature. When the ocean warms, my theory is that cumulus fields form earlier in the day and cover more of the surface, reflecting more of the sunlight back into space.

And when the ocean warms further, thunderstorms form that cool the surface in a host of ways. This keeps the earth from overheating.

Let me start with the issue of the increase in the strength and duration of the cumulus fields. This is reflected in the cloud area expressed as a percentage of the surface area. Here’s that chart.

Figure 4. NINO34 monthly cloud coverage percentages and sea surface temperatures.

Now, this is most interesting. As the temperature rises from about 26°C to its maximum just under 30°C, the total cloud area doubles, from 40% to 80%. This greatly affects the amount of sunshine reaching the surface, as we’ll see in a graph below of the net cloud radiative effect. And as is clear from the close correspondence of temperature and cloud coverage shown in Figure 4, the amount and strength of the cloud cover is clearly a function of temperature and little else.

Next, cloud top altitude. This is an indirect measure of the number of thunderstorms in the area. Here’s the graph showing the change in the number of thunderstorms with the changing sea surface temperature.

Figure 5. NINO34 monthly cloud top altitudes and sea surface temperatures.

Again we see a very large change. As sea surface temperatures go from ~26°C up to just below 30°C, the altitude of the cloud tops almost triples, from 5 km up to almost 15 km. And again, the number of thunderstorms is also clearly a function of the temperature and little else.

With these changes in mind, we can look at the cooling effects of these cloud changes. Figure 6 below shows the changes in the net surface cloud radiative effect. The net surface cloud radiative effect is the full effect of the clouds on the radiation reaching the surface. Clouds cool the surface by reflecting the sunshine back out to space and by absorbing solar radiation. They also warm the surface by increasing the downwelling longwave radiation. The net surface cloud radiative effect is the sum of these different phenomena.

Figure 6. NINO34 monthly net surface cloud radiative effect and sea surface temperatures.

Note that at all sea surface temperatures, the clouds cool the NINO34 sea surface. And as the temperature goes up the radiative cooling increases, and not by just a little—cooling goes from -10 watts per square meter (W/m2) to almost -60 W/m2 of cooling.

It’s also worth noting that the effect is not linear—small deviations in temperature don’t cause the amount of increase in surface net radiative cooling that is caused by large temperature increases. This is shown by the large peaks in the blue line extending higher than the peaks in the black line.

Then we can also look at the cooling effects of the rain. As discussed above, one meter of rain involves evaporative cooling of the surface on the order of 100 W/m2. This allows us to convert rainfall figures to evaporative cooling figures, as shown in Figure 7 below.

Figure 7. NINO34 monthly rainfall evaporative cooling effect and sea surface temperatures. Note that the dataset is a year shorter, because the rainfall data ends in 2021

Here we see the same fivefold increase in cooling with the increasing temperature, but on a larger scale. The rainfall evaporative cooling goes from -50 W/m2 when the NINO34 area is cool to -350 W/m2 when the area heats up. And this effect is non-linear as well, as shown by the peaks in the blue line.

And finally, we can combine the separate effects of the net surface cloud radiative changes and the rainfall evaporative cooling to get the total cooling effect of the clouds on the NINO34 area, as shown in Figure 8 below.

Figure 9. NINO34 monthly total cooling due to clouds. This is the total of rainfall evaporative cooling effect and surface cloud radiative cooling. Again the dataset is a year shorter because the rainfall data ends in 2021

As this shows, the clouds have a very strong cooling effect on the NINO34 area. At the peak temperatures, the clouds are cooling the surface at the rate of -400 W/m2. In addition, the cooling increases faster and faster as the temperature rises, putting a hard ceiling on how hot the NINO34 area can get.

… and the alarmists are concerned about a change in CO2 forcing over the same period of 0.7 W/m2?

That’s lost in the noise compared to the 400 W/m2 peak cloud cooling.

Finally, please be clear that this huge increase in cloud-related cooling is not just happening in the NINO34 zone. It occurs anywhere in the ocean where the temperature exceeds about 25°C. Looking at the NINO34 zone is valuable because the temperature changes so much there, revealing the close connection between temperature and total cloud cooling. For the larger view, here’s a scatterplot of average gridcell sea surface temperatures from 2000 to 2021, versus average gridcell total cloud cooling. Note that in addition to the rapidly increasing cooling at temperatures warmer than ~25°C, the effect of the clouds is cooling over all parts of the ocean.

Figure 10. Scatterplot, total cloud cooling versus sea surface temperature. Blue dots are 1° latitude by 1° longitude gridcells.

And that’s the sum total of what I learned today …

My very best regards to all,

w.

AS ALWAYS, I ask that when you comment you quote the exact words you are discussing. This avoids endless misunderstandings.

“Again we see a very large change. As sea surface temperatures go from ~26°C up to just below 30°C, the altitude of the cloud tops almost triples, from 5 km up to almost 15 km.”

When cloud height rises, is there not more radiation to space from the condensation process as the cloud(s) forms? At 15 km there is a lot less atmosphere (with water vapor and CO2) to collect and return some of the heat of vaporization to the earth’s surface. Or perhaps the momentum of the hotter rising cloud(s) is sufficient to elevate the cloud height and condensation occurs at the same altitude regardless?

Yes, at the top of the troposphere, cloud radiation can only occur upward because there is no vertical temperature gradient acting in the tropopause, so heat is not dissipated in the troposphere.

It’s the opposite. Higher clouds are colder and emit less. OLR from Nino3.4 drops upto 70 W/m2 during the largest Ninos. LW to the surface increases upto 25 W/m2.

And enthalpy of vaporisation of pure water is 2429.8 kJ/kg at 30 degree C but 2500.9 at 0 degree C (not a given that it will happen before or after this temperature).

That’s a 3% difference. Do the Watts. I was gobsmacked a few years ago to learn, via Judith, that Gavin the Schmidt thought this was an easily ignorable problem in climate models.

Edit: I didn’t learn it entirely directly from Judith, of course. I was reading entries at her blog at Climate Etc.

______________________________________________

Learn something new every and now I’ll waste

time trying to think of a viagra joke that fits.

Even though I witness virga a lot in the summer, my inner 12 year old brain was difficult to stifle.

Same thing happens to me when discussing the 7th planet from the sun …

w.

Yeah, it’s not as funny now the pronunciation has been changed.

Let’s stick with the original

Sometimes, you can only laugh at the jokes nature sends your way.

I think the virga issue is a non event for energy calculations.

Let me explain.

Assume that 50% of the rain evaporates, it goes from liquid to a gas. That gas does not condense and form rain in the gauge, (else its actions could be ignored), So, where does it go?

I’d say it goes back up into the clouds. Effectively it takes NO part in the energy equations. The energy used to evaporate it is returned when the water condenses in the cloud. No nett change.

I think Willis has missed the energy returned from the condensing virga.

Ian, see my comment here.

w.

Willis,

The issue is the total system energy.

Look at it from another viewpoint.

If the rain and virga occurred over a warm ocean, the evaporation of the rain would occur, (as shown in the video), this would cool the ocean and send water vapour into the clouds.

So the ocean is locally cooled, and until it warms back up, it also reduces the potential to cause evaporation. The next rain will now occur LATER because the ocean will take longer to get warm and hence have a delayed, slower evaporation rate until the water again warms up.

The only driver for evaporation is energy into the system.

Or do you have another source of energy?

Eng, obviously the sun is the only significant energy input into the system. This is why thunderstorms form preferentially over solar-heated warm spots. And yes, you are correct, this locally cools the ocean. At which point the thunderstorm dissipates.

This is the beauty of emergent phenomena like thunderstorms. They emerge over the warm areas, cool them down, and vanish. In fact, because they are a two-fuel heat engine (heat and water vapor), thunderstorms can cool the ocean down to a temperature below the threshold temperature necessary to initiate thunderstorm formation.

And in this way, they serve to thermoregulate the surface temperature.

See my post The Details Are In The Devil for a discussion of these issues.

“Dang! I forgot virga!”

This has me wondering, does lightning also factor in?

The screenshot below shows a storm rolling through my locale right now, clearly showing immense lightning activity over Lake Erie. (The top picture is precipitation, the bottom is simultaneous lightning)

All this energy, is it significant in the heat transport of a thunderstorm, where does it come from, where does it go?

David,

Years ago I used to think how wonderful was the engineering, the chemistry, the physics that created the human body, so that I could anticipate seeing new models that could be used to learn how the body works – including, from older static to more recent dynamic effects.

The reality that no such useful modelling exists ought to be a restraint on what we can expect from climate models. The much more important human body models continue to seem to be a long way off right now, so should we not anticipate a further wait for useful climate models? The existing ones are rush jobs based on inadequate data and too much guesswork, They need to be much better before they are used to affect big national policy decisions by governments.

Geoff S

“They need to be much better before they are used to affect big national policy decisions by governments”

Agreed Geoff.

Unfortunately, in the popular mind, all the complexities and uncertainties of both the models and the real world are reduced to this:

When the water evaporates it cools the surrounding air at that the altitude of evaporation. So it’s cooling just above the surface that the liquid rain gets to hit and cool. So part of the same heat pump as the liquid rain.

I think the water vapor will have a downward velocity, somewhat less than the droplets being evaporated, until it nears the ground and then spreads as surface winds

I suppose that even with Viagra there’s still premature evaporation?

Depends on how hot it is.

The rate of equilibrium latent flux converges at a maximum (optimal) rate of surface absorbed solar power / 2 (or about 160/2 = 80). To increase latent flux by one unit requires 2 additional units of surface solar absorbed and the associated temperature increase.

In other words, to initiate a hydrological thermostat mechanism requires increased surface available energy. Hydrological sensitivity is probably in the range 1.5% – 3% per K which can only be initiated by increased absorption of the solar beam.

JCM,

Yes, but as happens time after time, we are dealing typically with the difficulty of measuring very small numbers with large uncertainty in a complex dynamic system.

One scenario sees these measurements in general to be sufficiently good to be used as they presently are.

The other scenario sees the numbers as bit players swimming in a Heinz 57 soup of uncertainty that cannot be made to taste good no matter how much salt is applied.

Methinks the latter is reality. Geoff S

it has nothing to do with the numbers; it’s about thermodynamic constraints. Deal with it at the boundaries. Either by available energy at the surface, or using the driving temperature difference between the surface and the outgoing radiation temperature. The numbers only confirm the turbulent cooling flux already operates at maximum.

I would note that 26ºC SST is considered by the National Hurricane Center to be the minimum SST needed to sustain a hurricane. The exponential increase of saturation vapor pressure of water with temperature is a very non-linear response to SST.

We had virga yesterday as southern moisture moved northward across the area.

We also had a sudden drop in afternoon temperatures of the incessant heatwave we’ve had in the area for over a week.

Thank you, Willis!

You are truly the ES 135 of posters! That’s some sweet music as you continue to pull back the curtains hiding the Climastrology Hoax from the more gullible (and more easily brainwashed) portions of the public.

Whether it is paid for by the Russians, the ChiComs, or the Western billionaires who profit from the government subsidies for their inefficient and unreliable tech; the narrative is crumbling and the cracks in the Climate Matrix are growing more and more apparent, due to you, and others here at WUWT, citing the REAL science!

Great Ceres stats analysis.

“Then the other day I thought “Dang! I forgot virga!”” Whether or not this applies, some not appreciated memorization is always necessary despite new math among others. Our son never had to memorize the multiplication tables, it shows. Then again I never memorized enough grammer. In hot Texas evaporation is common even after it hits the ground.

Willis,

It is very interesting that cloud height (fig. 5) appears to show a better correlation than cloud coverage (fig. 4) although both are very good. I think this means convective effects dominate the generation of clouds (obvious if you think about it). And water vapor content is one of the two things that make a parcel of rising air more buoyant than the surrounding air.

For the virga thing I need more coffee…it doesn’t take part in rainfall measurements, but also doesn’t take part in the surface heat balance except for making more clouds….and down here on the surface is where we measure weather and climate.

I think Fig 10 should have a “% ocean surface” scale as you once previously did for CRE vs Earth surface. Awaiting part 2 !

Yep. It is cyclic convective instability that creates the 30C sustainable limit in open ocean.

The SWR increases at twice the rate of OLR reduction over warm pools regulating at 30C. The negative feedback factor is 2 if you plot the SWR against OLR over warm pools once cyclic instability sets in. Very powerful negative feedback

As the solar peak moves northward and the NH warms up, there is more of the NH ocean hitting the 30C limit. The impact of convective instability and the inverse relationship between SWR and OLR is observable as a climatic shift in latitudes just north of the Equator over the CERES era:

?ssl=1

?ssl=1

So you have to believe that CO2 is causing a reduction in cloud at all latitudes except just north of the Equator where it is causing an increase.

Perihelion is in January, aphelion in July. For several thousand years, the difference between the northern and southern hemispheres will be apparen.

Evaporation depends on temperature and pressure. As long as the average pressure at sea level does not increase significantly, the maximum ocean temperature in the tropics will remain below 31 C and small percentage increases in CO2 cannot change this.

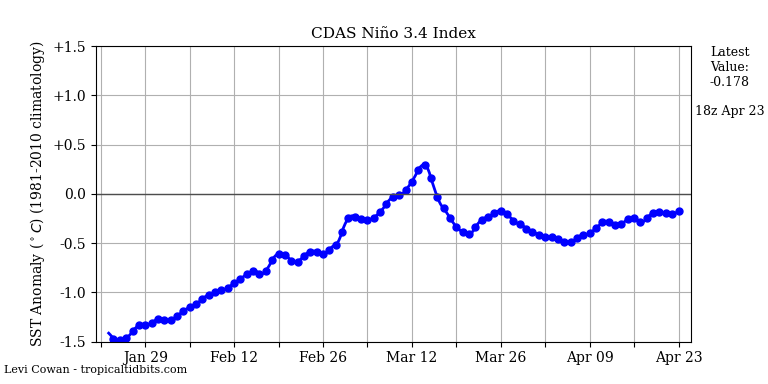

Once again, stratospheric ozone is falling and La Niña is at a standstill.

This sounds very dependent on local conditions. I New Mexico it isn’t uncommon for 100% of the rain to evaporate before it hits the ground. In south Louisiana on the other hand, where humidity is commonly in the 90s, rain often doesn’t bring much cooling, it just makes it muggy.

Given that how much rain evaporates as it falls likely depends on local conditions, and places that get lots of rain are usually more humid and therefore likely have less evaporation, I think that a lot more research needs to be done before we will even have a good global estimate from rain evaporation.

There should be some effect down to 0°C in fresh water, and below 0 in salt. I have observed the cooling effect from “lake effect” snow near fresh water.

Don’t forget sublimation. Water vapour is stripped from ice too.

Yes, but I haven’t got a sense that the process would cool anything. Drag (or friction?) might just balance out temperature change, and the air must be pretty dry for sublimation to happen. Down to about -5°C, the air will hold some moisture, and it will condense to liquid and then solid. Below that, I don’t know, and am pretty sure that it couldn’t be demonstrated easily without sensitive instruments. Whereas it doesn’t take much to directly observe lee side cooling from snow or sleet near a body of water..

No, the regulating process is the result of convective instability. That is only possible when a level of free convection can form. That requires at least 30mm of water in the atmosphere and that amount of water requires a miniimum surface temperature around 14C.

Below 14C, the atmosphere can sustain 100% humidity because there is no cyclic instability. Macquarie Island always provides a good view of what the atmosphere looks like over open ocean below 14C:

https://www.antarctica.gov.au/antarctic-operations/webcams/macquarie-island/

The persistent clouds that form over ocean below 14C help retain surface heat. The opposite of high cloud over 30C warm pools that have a powerful negative feedback. So powerful that the temperature limiting range around 30C is very narrow,

On the lee side of the Cascades of Washington I see virga frequently.

Video is by photographer and founder of Visit Austria, Peter Maier.

Nice post, WE.

A more general ‘sciency’ observation. When a theory is generally correct, as your thermoregulatory theory must be, it can be shown in many ways, with or without details like virga. As you have already shown many times.

Thanks, Rud, appreciated.

w.

Seconded. Geoff S

Wow, good work, and ‘cool’. Thanks doc.

Willis,

“Thus, the evaporation that creates the ~1 meter of annual rain cools the surface by – 80 W/m2.”

Yes. In Trenberth’s energy budget he had the same flux calculated in the same way.

“But I had overlooked the additional cooling from the evaporation of the rain itself.”

No. You were right to overlook it. The rain, in evaporating, provides vapor that will condense and warm somewhere else. It is a transfer of heat within the atmosphere, but where to where is unclear. It does not cool the surface.

Having witnessed a lot of virga, I’m torn on this post.

The clouds which usually come with virga have a cooling effect, as does the evaporated moisture.

Since there is no precipitation making it to the ground, the surface does not not cool from the physical effects of rain. However, the lack of direct sun light has a cooling effect on it’s own.

Shouldn’t this be accounted for?

I would also say there is a difference in cooling the air, particularly in the air above high altitude desert cities (such as Denver and Albuquerque) and cooling the surface of the same location.

As two separate effects of cooling, I believe it is right to treat them separately rather than having the same net effect.

Willis does a lot of accounting for cloud effects. There is increased albedo, which is accounted for. And there is sunlight thermalized, which means the heat just appears somewhere else.

It is a transfer of energy from lower in the atmosphere to higher in the regardless of its location. And energy higher in the atmosphere radiates to space more quickly. I don’t understand your reasoning when it’s the opposite of what CO2 is meant to do wrt warming by delaying the radiation to space.

Thanks, Nick. Look at the video again. First, if it is raining, the majority of the air and rain cooled by the evaporation goes straight down to the surface. In the tropics, the effect of this cooling of the surface and the air just above the surface is felt far from the rain itself. Indeed, it is the harbinger of the rain. Look at the wind in the video, blowing both cold air and cold mist across the surface of the lake …

In addition to cooling the air, the rain itself is cooled, and that rain most definitely cools the surface.

Second, with virga the air is cooled underneath the thunderstorm. So even with virga, much of whatever doesn’t go down to the surface will be drawn up with the other moist air into the thunderstorm itself, where it condenses at altitude and goes around the cycle again.

Remember that the issue here is the cooling of the surface, which definitely happens from the evaporation of the raindrops.

My best to you and yours as always,

w.

Thanks, Willis

“the rain itself is cooled, and that rain most definitely cools the surface”

Sensible heat is small in this context. In the old units, latent heat is 540 cal/gm. The cooling carried by water 10C less than ambient is just 10 cal/gm.

But the key issue is proper accounting for surface fluxes. Evaporating raindrops take heat from the air, and some of that will be near the surface, and likely came from the surface. But it will have come by one of the surface loss mechanisms – radiation, turbulent diffusion or latent heat, so is already accounted for.

If you do want to allow for evap from rain drops, you also have to allow for growth by condensation. In the tropics, particularly, air is near saturated during rain, and the drops are cooler than the air. In those conditions you get condensation, not evaporation.

And then at some later point condenses higher up in the atmosphere. So the energy was removed from the atmosphere nearer to the ground and released further away from the ground.

It’s the same for virga but doesn’t originate at ground level.

It is a cooling mechanism and I’m not quite sure why you refuse to acknowledge it.

Because it is double counting. If you have properly accounted for the fluxes at the surface (radiation, LH etc) then it just doesn’t belong. You have already marked that heat as emitted from the surface.

So your claim is that the cold water returned to the surface and the cold wind blowing across the surface are already accounted for?

I’ve been out in the tropics in my usual shorts and t-shirt in tropical downpours on a hot day and been chilled to the bone … but according to you, I’m not cold, that’s “double accounting”.

Sorry, not buying that one.

w.

It’s to do with time. Just like the AGW argument is.

Thunderstorms are surrounded by cool dry descending air which has had the water stripped out of it by condensation within the storm. So no, the air around tropical thunderstorms is NOT “near saturated”.

w.

“ So no, the air around tropical thunderstorms is NOT “near saturated”.”

No, but it is not where the raindrops are – or at least most of them. What counts for condensation/evaporation of rain is the air at the raindrop surface.

“condensation within the storm” does not sound like evaporating rain.

Thanks, Nick. A couple of points.

First, in general, the air circulating underneath a thunderstorm is moving inward and upward to the heart of the storm at the condensation level. That air is constantly being replenished by the descending dry air surrounding the thunderstorm.

The bottom layer of the in- and up-welling air under the storm is picking up water vapor from the surface. However, the air above that surface turbulent layer is also moving in- and up-wards. And that air is dry.

And of course, as soon as the rain starts falling, it’s falling through that dry air under the base.

Next, as the video shows, the dry air under the storm is entrained by the rain and forced down to the surface. As it is forced down, the pressure increases. And because temperature in this situation follows the dry adiabatic lapse rate of ~1°C/100 meters, the air is warming as it falls. Air temperature warms about nine degrees C° by the time it gets to the surface.

And the point is this. The warmer the air, the lower the relative humidity. If the air just underneath the storm bottom is at 9°C and as much as 50% RH, by the time it gets to the surface it will only have 28% RH (calculator here)

Both lines of evidence show that the air underneath the storm is quite capable of taking up more water vapor.

And this is borne out by studies such as the one I cited in the head post showing that 65% of the rain in their study evaporated. True, it’s northern ocean, but the RH over the ocean is suprisingly even pole to pole.

Anyhow, those were my thoughts after sleeping on the question.

Regards,

w.

Yep – He should only be accounting for surface fluxes.

Over warm pools, around 50% of the sunlight that does get thermalised just warms the atmosphere. It does not make it to the surface.

Something to think about. When a radiosonde measures low humidity at some altitude, does it mean that the atmosphere is free from water or just free from water vapour?

And another very important feature of water in the atmosphere. Without convective instability, Earth would be an ice ball. All the ice would be on the surface rather than some of it being in the atmosphere.

Moreover, with the decline of ozone in the stratosphere, water vapor over the equator will absorb all of the increase in high-energy UVB.

You need to better define your term “surface”. Is it the surface of the ocean or is it the atmosphere directly above the ocean surface?

It can’t be the ocean surface or it would be considered rainfall. If it is the atmosphere directly above the ocean surface then the heat contained in the atmosphere would be used to again evaporate the liquid rainfall and thereby cool the atmosphere.

Willis, you say:

Note that at all sea surface temperatures, the clouds cool the NINO34 sea surface.

However, from all of your graphs, Figures 4 through 9, it is clear that the sea-surface temperature leads cloud cover and cloud cooling.

My interpretation would be that it is evaporative cooling from the sea surface, rather than clouds, that control the sea-surface temperature. The clouds are the result of this evaporative cooling.

In other words sea-surface temperatures drive atmospheric temperatures, and not vice-versa.

I would like to correct the last sentence in the above comment:

In other words sea-surface temperatures drive atmospheric weather, and not vice-versa.

“..sea surface temperature leads cloud cover and cooling…”

VERY ASTUTE OBSERVATION dh-mtl.

I think that probably means that CLEAR SKY lets more daytime sunshine warm the ocean than clouds prevent leaving IR at night….and clear sky lets more IR exit the water surface at night to outer space than clouds do…net effect is surface temp precedes cloudiness over a large averaged area.

Still wrong

Thanks, lgl. You have a link to the source?

And it’s totally unclear who you are saying is “still wrong”, which is why I ask people to QUOTE THE DANG WORDS YOU ARE DISCUSSING!

W.

It’s from here: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336756219_Past_and_possible_future_influence_of_the_Atlantic_Meridional_Overturning_Circulation_on_the_climate_responsible_for_concentration_of_geopolitical_power_and_wealth_in_the_North_Atlantic_region

but the real source is probably: https://scienceweb.whoi.edu/oaflux/papers/YU-evp-JC2007.pdf

more here: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237440650_Multidecade_Global_Flux_Datasets_from_the_Objectively_Analyzed_Air-sea_Fluxes_OAFlux_Project_Latent_and_Sensible_Heat_Fluxes_Ocean_Evaporation_and_Related_Surface_Meteorological_Variables

Your idea that rain=evaporation at a location is wrong.

Very nice Willis.

From KNMI

What are we physics? You didn’t answer the question.

Psychics

Here is a better one

From https://climexp.knmi.nl/selectfield_rea.cgi?id=someone@somewhere

For some Ninos Willis is less than an order of magnitude wrong 🙂

In my view the Eschenbach ITC Global Thermostat theory is one of the great scientific advances in world history.

But there’s a problem, Willis. You make it all such Fun. This is wrong. Science should not be Fun. It should be Hard.

Does the recycling in the atmosphere make any difference to what occurs on the surface as the same amount of water evaporated returns as rain minus the heat?

You can argue that the “virga” absorbed energy at a different location in the atmosphere but it is certainly not at the surface, so the cold higher water saturated air slides over the surface and that is a cooling influence the whole Nick S dismissive narrative is ridiculous.

Ultimately if you go back into Miocene and look at the surface water temperatures in the tropical regions you can see from Foramin deposition they were quite similar to to now with a background global average atmospheric temperature around 5C higher.

The foramin temperature calibration is quite precise. We can say that as the world slide into the glacial phase 2.55 million years ago the tropical waters may have reduce in area but not in temperature.

How does a pool of warmer water in the Pacific Ocean warm the globe significantly in less than one 1 year?.

Advection moves the energy from the tropical regions to the polar regions every day that’s what makes weather LT3

Three sub parts, all taught me on one day by MIT’s Lindzen days before he retired, while commenting on the very long climate chapter to my then not yet published ebook ‘The Arts of Truth’.

So, you are saying it is conduction? That does not jive, a warm pool of water less than 1 percent of the surface area of the planet cannot possibly radiate heat to the other side of the world.

The Hadley cells are working continuously to transfer the equatorial heat polewards, it has to be the additional water vapor entering the atmosphere that causes the ENSO warming.

It is radiative, if it is not, that means when you start your car and it warms up, the heat from your engine has a direct effect, ever weak, in melting the cryosphere.

INMHO.

Yes, but understand that we are talking about a rectangle of warmer water 1 or 2 degrees above average, that is < 1 percent of the global surface area. And that somehow pushes temps up significantly in less than 1 year.

Care to take another stab at it?

LT3:

The answer is that atmospheric temperatures rise FIRST, causing a warming pool of water to form in the Pacific ocean.

That is not it, the ENSO phenomena is definitely a forcing that precedes global temperature state changes.

LT3:

The National Bureau of Economic Research has a publication titled “US Business cycles and contractions”, which lists 33 such events between 1853 and 2007.

During each cycle, factories, foundries, smelters, etc. are idled, and temperatures rise because the amount of industrial atmospheric SO2 aerosol pollution is reduced.

Of the 33 events, 14 caused temperatures to rise enough to form an El Nino, .

In these instances, global warming clearly PRECEDED any warming of the ENSO region, as I had stated.

Interesting, do you think some of these small perturbations that are occurring every couple of years show up in Transmission could be some of these event?

Sorry, left off Transmission

The triple dip La-Nina starting in 2020 is very unusual.

LT3:

The attached chart shows the correlations between American business recessions and temporary Global temperature increases, if I can attach it. Receive message: “This file type is not allowed on this site”

Will keep trying.

LT3:

Another attempt:

Temporary increases in in average anomalous global temperatures are identified with a black dot, and dates of occurrence.

First a general thanks for your great work with graphics and how it succinctly illuminates complex phenomena.

”Virga” – I had never heard the term before but it substantiates my observation of long ago that high cloud rarely results in rain. Clearly the rain has evaporated before it reaches the ground so no liquid although there may be a slight mist or drizzle at ground level.

Figure 10 – neatly explains the observation that Hurricanes do not form before the sea surface temperatures exceed 26C or so. It is at this point that the cooling effect accelerates rapidly making a huge amount of energy available to drive the winds.

You might want to call Figure 10 the “the Elephant’s Trunk Curve” in contrast to the hockey stick.

Just a smartass addition to my previous comment

”Figure 10 is truly the elephant in the room of the hockey stick”

bit slow this morning

That rising water loses another 15% of it’s heat if it freezes in the upper atmosphere, which I don’t know how much freezes, but I’d expect that percentage to be very high.

Thus, if 80 Watts was removed by going from liquid to vapor, another 12 Watts was removed if all the water froze.