From the Carnegie Institution – maybe we should build more cooling towers.

Washington, DC. — Scientists have long debated about the impact on global climate of water evaporated from vegetation. New research from Carnegie’s Global Ecology department concludes that evaporated water helps cool the earth as a whole, not just the local area of evaporation, demonstrating that evaporation of water from trees and lakes could have a cooling effect on the entire atmosphere. These findings, published September 14 in Environmental Research Letters, have major implications for land-use decision making.

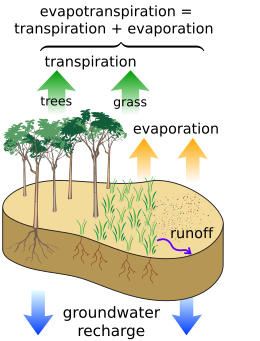

Evaporative cooling is the process by which a local area is cooled by the energy used in the evaporation process, energy that would have otherwise heated the area’s surface. It is well known that the paving over of urban areas and the clearing of forests can contribute to local warming by decreasing local evaporative cooling, but it was not understood whether this decreased evaporation would also contribute to global warming.

The Earth has been getting warmer over at least the past several decades, primarily as a result of the emissions of carbon dioxide from the burning of coal, oil, and gas, as well as the clearing of forests. But because water vapor plays so many roles in the climate system, the global climate effects of changes in evaporation were not well understood.

The researchers even thought it was possible that evaporation could have a warming effect on global climate, because water vapor acts as a greenhouse gas in the atmosphere. Also, the energy taken up in evaporating water is released back into the environment when the water vapor condenses and returns to earth, mostly as rain. Globally, this cycle of evaporation and condensation moves energy around, but cannot create or destroy energy. So, evaporation cannot directly affect the global balance of energy on our planet.

The team led by George Ban-Weiss, formerly of Carnegie and currently at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, included Carnegie’s Long Cao, Julia Pongratz and Ken Caldeira, as well as Govindasamy Bala of the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore. Using a climate model, they found that increased evaporation actually had an overall cooling effect on the global climate.

Increased evaporation tends to cause clouds to form low in the atmosphere, which act to reflect the sun’s warming rays back out into space. This has a cooling influence.

“This shows us that the evaporation of water from trees and lakes in urban parks, like New York’s Central Park, not only help keep our cities cool, but also helps keep the whole planet cool,” Caldeira said. “Our research also shows that we need to improve our understanding of how our daily activities can drive changes in both local and global climate. That steam coming out of your tea-kettle may be helping to cool the Earth, but that cooling influence will be overwhelmed if that water was boiled by burning gas or coal.”

Freeman Dyson’s comments in this 2008 NY Tiimes book review are still worth reading on the economics and science of tree-planting, especially his apparent support of the the Nordhaus plan to genetically-engineer “carbon-eating trees”.

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2008/jun/12/the-question-of-global-warming/?page=1

Bruce says:

September 16, 2011 at 8:30 am

So, deforestion causes possible global warming, increased solar activity posiibly causes global warming, black soot, black roof-tops, land use changes all cause warming…. With 0.8 degrees C warming over the last 150 years, where is CO2′s slice of the pie?

Josh’s Theo ate it.

Burp.

So more water vapour in the air leads not to a positive temperature feedback, because water is such a powerful GHG, but to a cooling, because water vapour and clouds are such weak climatic forcing agents.

Warmcool, strongweak, it all works.

The tiaga in Russia spans thousands of mile. The forests of Canada the same. The forests in the temperate zones are immense. The idea that the cooling is not global is well silly.

GB Dorset says:

September 16, 2011 at 4:15 am

Increased CO2, increased plant growth, more evaporation, more clouds, more reflection, cooler planet.

There can be no doubt that plants cool the earth. This paper by Frank et al. (causes and timing of future biosphere extinctions):

http://www.biogeosciences.net/3/85/2006/bg-3-85-2006.pdf

Shows that the appearance of multicellular life, including the colonisation of land by plants and formation of soils, was accompanied by a sharp drop in global temperature in the early phanerozoic that has been favourable to life – the Gaia paradigm.

Further, this paper by Beerling and Berner (feedbacks and the coevolution of plants and atmospheric CO2):

http://www.pnas.org/content/102/5/1302.full.pdf

show that any relationship between CO2 and global temperatures (leaving aside the issue of time lags) does not necessarily imply any direct physical effect of CO2 on temperatures via radiative balance – this notion having been torpedoed in any case by Roy Spencer. Beerling and Berner show that falling CO2 in the Devonian / Carboniferous was directly caused by evolution and spread of trees with ever wider leaves and more leaf stomata, and greater tree height. A positive feedback prevailed in which plants sucked CO2 out of the air and in response became more efficient at using diminishing atmospheric CO2. We now have confirmed by the paper reported in this post the obvious fact that plant and tree transpiration causes cloud formation and cooling (since – thanks to Bill Illis – we also have confirmation of the dominant effect of cloud cover on global radiative balance.) Thus cooling that accompanied falling CO2 was due to plant transpiration and cloud formation, not any physical effect of CO2. In any case changes in global temperature and CO2 over earth’s history are grossly mismatched and noncorrelated:

http://img801.imageshack.us/img801/289/logwarmingpaleoclimate.png

http://www.biocab.org/Geological_Timescale.jpg

In short – the relation between CO2 and global climate is entirely biological, not physical – it is mediated by plant metabolism and transpiration.

The conservation of trees and vegetation covered land area is a much more important issue than atmospheric CO2 which is secondary and more or less irrelevant to any consideration of environment and temperature.

Doug, you said:

“So more water vapour in the air leads not to a positive temperature feedback, because water is such a powerful GHG, but to a cooling, because water vapour and clouds are such weak climatic forcing agents.”

Water vapour and clouds are STRONG forcing agents. Water vapour may be a strong GHG but note that water vapour in the atmosphere varies hardly at all because the water cycle speeds up to keep it stable. That is why there is an overall negative feedback.

Instead of global humidity increasing we see a faster water cycle so that the effect of GHGs in slowing energy transmission to space is negated by a faster energy transmission to space by the faster water cycle.

Non radiative processes cancel out the radiative effect of GHGs.

Evaportation also moves the heat aways from the surface, circumventing the GH effect and releasing heat higher up, where it is less likely to be make its way back down to the surface.

There are a few misconceptions, or wrong assumptions in this thread that make some of the posts contradict or refute each other…

1)- Increased CO2 causes increased plant activity which increases evaporation from plants.

But increased CO2 means plant can reduce the time they open the stomata that let in CO2 and let out the water vapor. Studies show plants are more resilient to drought when CO2 is high because they can reduce the transpiration/evaporation from stomata.

2)- Increased evaporation = increased low cloud = cooling.

This is the Carnegie studys’ justification for claiming that the net global effect of local increases in evaporation is cooling.

But while low thick cloud cools during the day by reflecting more sunlight, it warms during the night by back radiation. As another poster noted, introducing a water feature or park to an urban environment reduces peak daytime temperatures and increases minimum nighttime temperatures. The characteristic of a ‘greenhouse’ effect.

3)- Evaporation removes energy from the surface without raising the temperature and carries that energy as latent heat into higher altitudes where on condensing, it escapes more easily to space.

But the rate at which energy is lost from an object depend much more strongly on its temperature than its altitude. E==T^4

The low cloud from extra evaporation is at a lower temperature than the surface it came from, it will emit energy at a significantly lower rate than the evaporating surface. It will certainly emti energy at a much lower rate than the much higher surface temperature if evaporation had not stabilized the surface temperature.

This is why dry deserts get hot – but freeze at night while the oceans at the same latitude have a stable temperature.

The hydrological cycle transports energy around but cannot create or destroy it. It has a profound effect on the spread, the variability of temperatures on a local and global scale, but little effect on the total energy content of the environment. It alters the distribution rather than the mean, the area under the curve stays the same.

izen:

1) If there is adequate water the plant increases growth rather than shutting down stomata. Over most of the Earth there is plenty of water.

2) The energy value of the shortwave reflected is always greater than that of the longwave which is slowed down in its exit from the system. Shortwave reflected is lost to the system altogether but downward longwave cannot develop unless the shortwave enters the system first so less shortwave getting in also reduces downward longwave.

3) The cloud itself might emit at a lower temperature than the surface but that is irrelevant. The cloud only forms AFTER condensation and it is the process of condensation that dumps energy at the higher level for faster exit to space.

So all three points are utter rot and reek of desperation.

The water cycle speeds up energy transfer from surface to space by non radiative means and thereby offsets the slowing down of energy transfer from surface to space from the radiative characteristics of GHGs.

AGW is not plausible.

Anybody have a copy of this paper, doesn’t even appear under accepted papers. Interested in the methods.

British climate cooling experiment.

Trees do the metabolism thing, too. Building and consuming sugars, etc. Especially at night, they thus contribute heat to the mix.

Evaporation changes due to tree cover is a factor to the extent the evaporation would not have occurred otherwise. I.e., change in total evaporation is what needs quantifying. That would also imply increase in RH and/or speedup of the hydrological cycle.

Does anyone have a link to a recent study/paper I seem to recall, that found that forested/vegetated areas of the planet are on the whole warmer than less bioactive ones? I can’t locate it.

Oliver OFlynn says:

September 16, 2011 at 3:57 am

Oliver, Last time I did the calculation total energy useage by the human race was 1/10,000 of incoming solar. Temperature increase less than .01 deg C

OK. So benign green water vapor, evaporated by sweet breezes from stomata of silky leaves cools the planet, while evil black water vapor, evaporated from wind driven angry sea spray by nasty downwelling thermal radiation warms it. Understood, it’s simple as a wood wedge.

The significance of this is that it calls further into doubt the validity of the surface temperature measurements as a measure of ‘global warming’.

This is because surface temperatures are predominantly measured in cities and agricultural areas.

And as the study points out the 2 competing effects of more/less trees (and of course more/less irrigation) occur in different places.

There is an increased water vapour GH effect where the the WV is introduced into the atmosphere (ie warming) and increased cloud reflectivity downwind (ie cooling).

Thus the 2 competing effects occur at different places and times.

One example is here in Perth, Western Australia where there is extensive urban irrigation – people like green gardens and lawns, even in a hot arid climate like ours. The hotter it gets the more they irrigate and as I have remarked before the resultant near ground humidity is noticeable on hot days.

However, this near ground humidity doesn’t result in cloud formation locally, because the layer of humid air is too shallow.

Eventually this water vapour will form into clouds but that will be either far out over the Indian Ocean or far into the interior, where there are almost no temperature measuring surface stations.

Fail

“The researchers even thought it was possible that evaporation could have a warming effect on global climate, because water vapor acts as a greenhouse gas in the atmosphere. Also, the energy taken up in evaporating water is released back into the environment when the water vapor condenses and returns to earth, mostly as rain. Globally, this cycle of evaporation and condensation moves energy around, but cannot create or destroy energy. So, evaporation cannot directly affect the global balance of energy on our planet”.

They should pay greater attention to the changes that pressure differentials have on enthalpy and sensible heat of a mass of water being transported by convection from the surface of the earth to any height of cloud formation. If they did they would determine, the nett effect of evaporation from the surface to the height of cloud formation, bypasses the greenhouse effect by transporting “hot” water vapour to heigher levels of the atmosphere and lower pressures. Such that, at the point of condensation to “cold” water the radiation captured by the surface water is miraculously released back into space, i.e. a nett negatiive feedback of the climate system.

I don’t want to rock the boat here but clouds can also produce a warming effect. Clouds radiate heat back to the earth. That produces a warming effect. There is a simple experiment to demonstrate it. You need an infra-red thermometer. These usually cost less than $100.

On a summer day when the ambient temp was about 75F I aimed my infra-red thermometer at a patch of clear blue sky. The reading was -18F. Then I aimed it at the underside of a low cloud. The reading was 45F. That’s a huge difference. The energy radiated from a warm body is proportional to the fourth power of the absolute temperature. So something at 45F will radiate 70% more energy back to the earth than something at -18F.

Of course clouds reflect sunlight and that produces a cooling effect. But which dominates the cooling effect or the warming effect? There is another factor that would have to be considered too. That is the emissivity of the cloud and of the clear blue sky.

izen says:

September 16, 2011 at 11:50 am

But while low thick cloud cools during the day by reflecting more sunlight, it warms during the night by back radiation.

So here’s the dilemma – clouds reflect sunlight during the day back out to space (albedo), a cooling process, while at night they reflect radiated electromagnetic thermal energy from the earth’s surface back down – a warming process.

So here’s the really tough question – which process predominates, the day albedo or the night “insulation”? Is the net effect warming or cooling?

Another way to phrase this (really difficult) question is, which is warmer, day or night? Or – which radiation is more intense and energetic – that from the sun, or that from the earth during the night.

Any takers?

@- enthalpy says:

September 16, 2011 at 5:54 pm

“Fail…

They should pay greater attention to the changes that pressure differentials have on enthalpy and sensible heat of a mass of water being transported by convection from the surface of the earth to any height of cloud formation. If they did they would determine, the nett effect of evaporation from the surface to the height of cloud formation, bypasses the greenhouse effect by transporting “hot” water vapour to heigher levels of the atmosphere and lower pressures. Such that, at the point of condensation to “cold” water the radiation captured by the surface water is miraculously released back into space, i.e. a nett negatiive feedback of the climate system.”

I would be interested in seeing calculations that supported this claim.

If it is a natural physical process that governs the release of energy back into space, rather than a miraculous one, then the claim seems to be that a mass of air and cloud a mile high will release more energy to space than the surface which is 10 degK warmer.

How much easier is it for energy released at cloud height to reach space compared to ground level? I think you may need to use the radiative transfer equations to determine this, and I suspect the claim of a net negative effect may be difficult to justify.

phlogiston and izen.

I dealt with both your points upthread as follows:

“The energy value of the shortwave reflected is always greater than that of the longwave which is slowed down in its exit from the system. Shortwave reflected is lost to the system altogether but downward longwave cannot develop unless the shortwave enters the system first so less shortwave getting in also ultimately reduces downward longwave..”

By definition shortwave has greater energy content than longwave which is why it can penetrate the oceans up 200 metres.

and:

“The cloud itself might emit at a lower temperature than the surface but that is irrelevant. The cloud only forms AFTER condensation and it is the process of condensation that dumps energy at the higher level for faster exit to space.”

After all the air at the higher level never gets as warm as the surface when the energy is dumped by condensation. Instead it goes straight out to space for virtually no effect on the cold temperature at the higher level.

400 ppm of CO2 is the same as 40 molecules of CO2 amid 99,954 molecules of nitrogen and oxygen, and about 6 molecules of other trace gasses. Of that 40, about 2.5% is caused by human activity, which equals a single molecule of CO2, amid 99,999 other “natural” molecules.

To think that a change in the temperature of a single molecule could have any measurable temperature change effect on 99,999 other molecules is absurd, however warm the single molecule became.

Of course additional CO2 would cause the temperature of the planet to become cooler. Transpiration of water from the greater abundance of green plants would result in more cloud cover, which would increase the albedo of the planet, and more, in the tropical and temperate latitudes, where the intensity of sunlight is the greatest.

CO2 also is the sole source of the oxygen in the air we and other animals have to breath to live, and provides to green plants one of the three fundamental components, carbon, along with water and light, that green plants must have to even exist.

@- LarryOldtimer says:

September 17, 2011 at 12:20 am

“400 ppm of CO2 is the same as 40 molecules of CO2 amid 99,954 molecules of nitrogen and oxygen, and about 6 molecules of other trace gasses. Of that 40, about 2.5% is caused by human activity, which equals a single molecule of CO2, amid 99,999 other “natural” molecules.”

You have made the mistake of counting all the NON ‘greenhouse’ gas molecules, to get a sense of how significant the change in CO2 might be try just counting the GHGs.

-“To think that a change in the temperature of a single molecule could have any measurable temperature change effect on 99,999 other molecules is absurd, however warm the single molecule became.”

A single molecule does not really have a ‘temperature’. That is a collective property of matter which expresses the averaged kinetic energy of the molecules. As such the addition of just one molecule to millions will still have an impact on the bulk average. This is because the molecules of a volume of air rapidly share their kinetic energy by collision.

@- Stephen Wilde says:

September 17, 2011 at 12:03 am

“The cloud itself might emit at a lower temperature than the surface but that is irrelevant. The cloud only forms AFTER condensation and it is the process of condensation that dumps energy at the higher level for faster exit to space.”

HOW much faster?

I am still interested in some calculations that would justify the claim that a body of air and water droplets at cloud height and near to freezing releases energy to space faster than a warmer surface at a lower altitude. Given the depth of the atmosphere cloud height is only a small fraction of the way out to space for emitted LW radiation so the advantage would seem to be small. But emission of energy is massively changed by temperature, proportionate to its 4th power.

-“After all the air at the higher level never gets as warm as the surface when the energy is dumped by condensation. Instead it goes straight out to space for virtually no effect on the cold temperature at the higher level.”

There IS an effect, it is the source of the difference between the dry and wet adiabatic lapse rates. Science of Doom (the link is in the right hand list) has a good exposition of the way energy is moved by evaporation and water vapor by convection. He at least puts some numbers on the size of the effect…

“the claim that a body of air and water droplets at cloud height and near to freezing releases energy to space faster than a warmer surface at a lower altitude.”

No one is making that claim.

Instead the claim is that when vapour condenses out there is a release of latent heat at the higher level which is instantly lost to space by radiation upwards.

Since that latent heat does not affect temperature (hence the term latent) it plays no part in the greenhouse effect and so the transfer of latent heat by non radiative means is an ADDITION to the transfer of sensible heat by radiative means.

So more evaporation which always involves latent heat always results in faster energy transmission than radiation alone.

Asking for figures to prove that simple well established fact is just daft. It’s like saying you don’t accept Newton’s laws of physics without figures in support or you don’t accept E=mc2 from anyone who doesn’t go through the proof with you.

I’ve been very surprised to find ,here and elsewhere, how those who believe in AGW seem never to have picked up the long established physics of the phase changes of water.

Crispin in Waterloo

The best correlation for long temperature trends is with the solar wind with a lag of 4-8 years. However it tends to track less well since 1970 when temperatures moved ahead of the geomagnetic activity index. See for example this link which discusses the breakdown after 1970.

http://www.academicjournals.org/ijps/pdf/Pdf2006/Oct/El-Borie%20and%20Al-Thoyaib.pdf

It’s possible that accelerated deforestation since 1970 may have added the extra warming through loss of forest cover (and yes folks its an anthropogenic global warming effect).

I have linked here a pretty basic summary of global deforestation trends which discusses how some areas are recovering (Asia and North america) and some areas continue to lose forests (africa and south america).

http://www.environmentaltrends.org/fileadmin/pri/documents/2011/Forests.pdf

Overall we have lost 3% of the worlds forest cover over the last 20 years (likely its about 6% since 1970). I think that cloud cover variability is primarily influenced by deforestation and cosmic ray fluxes and its an additive effect and these factors are the primary drivers of long term tempertaure trends. I think the primary driver is celestial ( cloud cover changes from changes in galactic comic rays) and the secondary factor of deforestation is anthropogenic.