By Andy May

There have been many attempts to compare wind and solar power generation to generation with natural gas and other fossil fuels. I have summarized and criticized these attempts before, see here and here. Another excellent discussion of the topic is in this TPPF report by Michael Reed and Brent Bennet. Reed and Bennett estimate that modifying the Texas grid to handle wind and solar output variability cost Texas electricity consumers $2.3 billion in 2023. The purpose of this post is not to cover the whole issue, as Reed and Bennett do, but only discuss how to account for the natural gas swing generation used to backup wind and solar when these sources are unavailable, like on windless nights. The power one can produce using wind turbines and solar panels varies a lot from place to place and from time to time. Figure 1 shows the mix in Texas on 27 January 2026 at 12:21PM.

Texas, as a state, ranks #1 in wind generated power, #2 in

Texas, as a state, ranks #1 in wind generated power, #2 in solar, and #1 in net annual overall electricity generation. As you can see in figure 1, sometimes, on a clear day, with sufficient wind, solar and wind power supply much of the electricity used in Texas. Texas generates over 500 TWh (terawatt-hours) of electricity (588 TWh in 2025). According to ERCOT natural gas accounts for about 41% of Texas electricity production and most of that is from natural gas combined cycle (NGCC) generators. Wind is about 24%, solar 14%, and nearly all the rest is from coal (13%) or nuclear (9%).

Wind and solar are intermittent sources and can fall to zero production without warning. Coal and nuclear are only adjustable within certain limits, neither can change their electrical output quickly or by very much. Coal and nuclear can ramp up or down by as much as 1-3% per minute or so with care, but they are not well suited to rapid response. Only natural gas generators and batteries can change output quickly and by large amounts, they are the swing generators. Natural gas plants can start up in minutes and ramp at 20% to 50% per minute.

Battery storage systems have exploded within ERCOT, and they provide the fastest response, on the order of milliseconds. As a result, they act as ultra-fast swing resources. However, for sustained emergencies (more than 1-2 hours) natural gas plants dominate. They are also the only generators that do not require outside backup, since they are their own backup. If they run at 80% of capacity, they can ramp up and down with demand. They are an ideal partner for coal and nuclear.

Who pays for backup reserve power?

Given that NGCC can provide their own backup power, their backup costs are logically zero. Battery storage (or “BESS”) systems are only for backup and cannot provide base load as their effective time on the grid is very short, less than two hours for most systems. Their advantage is they can provide emergency power almost instantaneously. But they must be recharged and kept fully charged, so they do have a fuel cost. Table 1 compares all these commonly used systems and provides a total cost for each per megawatt-hour (MWh) of produced electricity.

Lifetime capital cost at 7%

As you can see in Table 1, I compute the installation cost in dollars per MWh (Megawatt-hours) of electricity produced. It includes equipment and installation costs amortized at a 7% annual annuity rate, over the expected lifetime of the installation. The numbers given are for Texas in the 2023 to 2025 years and they are in the range of those reported by NREL, Lazard, and EIA. The range of costs per MWh for wind and solar are extremely variable since they change a lot by location and by production per year assumed. Texas wind generation has a cumulative capital investment of $55.6B, a 40.7GW generation capacity, with a 33.6% capacity factor, and a 25-year lifetime, so using a 7% annuity discount yields a $39.80/MWh discounted cost, not counting subsidies, which are about $10 per MWh. The full range of costs in the sources cited above is from $20 to $86 per MWh, which is so large as to be meaningless. One of the reasons I chose to focus on Texas is it narrows the range.

In Texas, a very sunny state, I derived a value of $40 per MWh for solar. Again, the values from NREL, Lazard, and EIA are all over the place and range from around $25-$45 per MWh. We used an installed capacity of 16 GW, a 23.5% capacity factor, an equipment cost of $21.5B, and a 27-year lifetime to get $40/MWh.

Most of the Texas fleet of natural gas generators are the efficient combined-cycle type (NGCC). These high efficiency, fast spin up generators use a natural gas burner to spin a gas turbine and then use the excess generated heat to spin a steam turbine for extra electricity output. They are the most flexible and efficient electricity generators, and they provide their own backup because they can be throttled down quickly when demand is lower and then quickly spun up when demand rises. Their only downtime is for maintenance, which can be planned for. Texas also has some conventional natural gas generators which are normally offline and are used as “peakers” to supply extra power at peak demand or on windless and cloudy days or at night.

NGCC plants are often throttled back to use wind and solar power on good days, because once installed and operating their fuel is free. This causes NGCC plants to have an artificially low utilization rate. But comparing actual NGCC utilization to solar and wind capacity factors is misleading, since the NGCC low utilization is a choice, and not forced by weather. An NGCC utilization rate of 80%, absent solar and wind is reasonable because this rate allows for maintenance time and can provide a backup spinning resource for emergencies. Thus, rather than using the actual utilization rate for our comparison I used 80% and a 27-year lifetime. This lowers the cost/MWh significantly from other published amounts and results in $25.30/MWh.

Subsidies

Texas doesn’t have any significant electrical plant subsidies, although some local communities may offer tax abatements to attract a facility, these are offered to all types of energy plants, so we will ignore them. The federal subsidies are specific as to the type of energy produced. For wind we use $9.95/MWh, which aligns reasonably well with the TPPF and EIA estimates. Our solar estimate of $25/MWh is a little high, since the national estimate by TPPF is $18-$20, but various LCOE sources (see Lazard here, page 9) suggest the number is $25-$40, thus $25 falls in the middle. Solar subsidies are higher than for wind in absolute terms and made higher per MWh because solar has a lower capacity factor than wind.

NGCC electrical power receives almost no subsidies in the U.S., the range in the literature is between $0.50 and $1/MWh, and we use one dollar. These are not direct subsidies, like wind and solar receive but upstream tax preferences that some call subsidies, I didn’t want to get into that debate here, but have discussed the issue previously.

Operation and maintenance costs (O&M)

All electricity production facilities require ongoing maintenance, repairs, insurance, and must lease or buy the land they stand on. These costs are not as complex as those discussed previously and we use standard numbers here, $15.29/MWh for wind (published range ~13-17), $9.50/MWh for solar (published range ~7-12), and $6.60/MWh (published range $3-$5, ours is higher due to higher utilization (80%) for NGCC. NGCC gets a break on O&M because the land it uses is very small and the facility is enclosed so the equipment is not exposed to the elements.

Backup costs

The backup costs for intermittency (sometimes called renewable integration costs, grid balancing costs, or grid firming costs) are from TPPF and EIA. Failures of solar and wind generation that require backup are windless days, nighttime, and cloudy days. The backup costs are not paid for by the solar and wind facilities but spread out across the whole grid as increased charges to consumers.

In a 2025 TPPF analysis, the use of wind and solar caused the extra procurement of $788 million of power in 2023, which is roughly $6.30/MWh. The broader impact was in grid improvements to accommodate wind and solar generation, these cost $2.3B in 2023 or $18.40/MWh. Overall, according to TPPF (Bennet & Piracci, 2026), after adjusting for inflation and increasing electricity demand, ERCOT has paid 57% more in electricity transmission charges than in 2010. This is over one billion dollars per year to support solar and wind generation. Thus, the charges are not just for the electricity purchased to backup solar and wind facilities in unfavorable weather conditions ($6.30), but also the required changes to the transmission grid ($18.40). These values total $24.70 and are the total required for both wind and solar. Wind has a capacity factor of 33.6% and solar 23.5%, thus dividing by this ratio seems reasonable. It results in a wind backup cost of $7.42/MWh and a solar cost of $17.27/MWh.

Fuel

Fuel is free for wind and solar once installed and operational. The fuel for natural gas combined cycle is about $30/MWh. Assuming a battery round trip efficiency of 85-90% for the battery electricity (or energy) storage system (BESS) units and that they are charged with natural gas power, the fuel cost for the battery units is about $31/MWh. This is really the only fair way to compare the battery backup units, since they would not be needed if solar and wind were not in the mix.

BESS

The battery energy storage systems put into place in ERCOT and elsewhere in the country are useful short-term backup systems because they can supply electricity in milliseconds as needed. However, for longer blackouts, longer than about two hours, they will not work. However, as noted above, if it were not for solar and wind, they would not be needed. NGCC and regular natural gas generators can provide their own backup by throttling them back and allowing their output to go up and down with demand. Coal and nuclear are best as baseload producers.

Discussion

Adding federal subsidies to the discounted capital cost and the operational cost we reach the estimated full cost of the power source. This is $65.04/MWh for wind, $74.50 for solar, $32.90 for NGCC, and $79.00 for battery backup. Once the backup costs and fuel are added, we have a total cost of $72.46 for wind, $91.78 for solar, $62.90 for NGCC and $110.00 for battery backup.

Using this methodology, natural gas is the cheapest electricity, batteries are the most expensive, and solar is the second most expensive. In a sense this is misleading since if it were not for solar and wind, batteries would not be needed except for users that cannot stand an outage of a few minutes. Those customers could supply their own battery backup. Natural gas generators can ramp up to cover problems in a few minutes at most.

This sort of analysis is subjective in part and is always very controversial and open to debate, but it seems clear to this observer that wind and solar are not a net addition to the Texas grid, but a burden on it. Clearly the most efficient way to supply energy is with a coal and nuclear base power system with NGCC as a swing element to handle changes in demand and emergencies. Batteries will be needed by some customers but let them buy their own systems.

Works Cited

Bennet, B., & Piracci, J. (2026). The Explosion of Transmission Costs in ERCOT: Causes, Forecasts, and Policy Solutions. TPPF. Retrieved from https://www.texaspolicy.com/the-explosion-of-transmission-costs-in-ercot-causes-forecasts-and-policy-solutions/

Bennett, B. (2024). The Siren Song that Never Ends:Federal Energy Subsidies and support from 2010 to 2023. TPPF. Retrieved from https://www.texaspolicy.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/2024-10-LP-Federal-Energy-Subsidies-BrentBennett_FINAL-1.pdf

EIA. (2023). Federal Financial Interventions and Subsidies in Energy in Fiscal Years 2016-2022. Retrieved from https://www.eia.gov/analysis/requests/subsidy/pdf/subsidy.pdf

EIA. (2025). Levelized Costs of New Generation Resources in the Annual Energy Outlook. EIA. Retrieved from https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/electricity_generation/pdf/AEO2025_LCOE_report.pdf

ERCOT. (2026). Fact Sheet. Retrieved from https://www.ercot.com/files/docs/2022/02/08/ERCOT_Fact_Sheet.pdf

Lazard. (2025). Lazard’s 2025 LCOE. Retrieved from https://www.lazard.com/media/eijnqja3/lazards-lcoeplus-june-2025.pdf

NREL. (2024). Annual Technology Baseline: The 2024 Ele3ctricity Update. Retrieved from https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy24osti/89960.pdf

POTOMAC Economics. (2024). 2023 State of the Markey Report for the ERCOT Electricity Markets. Retrieved from https://www.potomaceconomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/2023-State-of-the-Market-Report_Final.pdf

Reed, M., & Bennet, B. (2025). The cost of wind and solar variability to Texas Ratepayers. TPPF. Retrieved from https://lifepowered.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/2025-02-LP-Cost-of-Wind-and-Solar-ReedBennett.pdf

January 26th, the coldest day of the year (on average) in the USA. Likewise July 26th is the hottest.

seems that way- gonna be sub zero F tonight and we have about 2′ of snow on the ground

amazingly, my 25 year old snowblower is still working fine- maybe another big storm this weekend

is your snowblower gas powered or electric?

FWIW – This morning, I just ran a quick calc of Mark Jacobson’s 100% renewable study for the US using his table S9 for installed capacity for 2050, then plugged in the actual capacity for the 1.20.2026 through 1.28.2026 (4amEst) using the EIA actual capacity numbers and actual demand #’s.

The result is that there is a 27 hour period starting on 1.24.2026 at 4pm and another 14 hour period starting at 5pm on 1.27.2026 whereby there is a 25%-30% shortage of electric supply (even including battery backup). This being the winter, there is very little excess electric generation capacity at other times to recharge the batteries.

Jacobson brags about his “Every 30 second stress test” which is dubious. One item worth noting is Jacobson appears to rely heavily on “averages”, average capacity, average demand, etc. Anyone that has worked in a manufacturing environment, knows that “averages” are a terrible metric when production is highly volatile, ie variable.

Andy,

“Texas wind generation has a cumulative capital investment of $55.6B”

But in the table, you have entered it as $55.6B/GW, and it seems that may have gone into the arithmetic.

Hi Nick,

Good catch. It should be $55.6B total and that is for 40.7 GW capacity. Combine with a 33.6% capacity factor, 25-yrs and a 7% discount rate yielding $39.8/MWh. The typo was adding the “/GW”. I’ve fixed it. The rest of the values should be OK.

Andy,

The table in the article is totally bogus, only good for deceptive PR purposes

No bank would loan money, no owner would invest, no insurer would insure, based on the table.

I am an energy systems analyst

I have prepared hundreds of multi year spreadsheets during my 40-year career

You get much better wind numbers if you amortize the bank loan for 25 years at about 6%, and if you amortize the owner investment over 25 years at about 9%.

BOTH HAVE TO BE PAID

Divide by the production and you get the cost per kWh

Add to that building the wind turbines, shipping by special ships, erection by special ships, project design/project management/licensing, O&M, Insurance, federal and state taxes, extra grid costs, counteracting/supplementing by other generators, disassembly at end of life, long-term storage of hazardous waste.

Initial Offshore wind will cost about 31 c/kWh, with some components increasing over time due to increasing costs, or 15.5 c/kWh after 50% subsidies and other financial incentives.

The 15.5 c/kWh is the initial wholesale price at which utilities are forced to buy the electricity

PS The cost of utility-scale battery backup is so high/kWh, it cannot be considered.

Sorry you don’t like the table, but it is fine and fits in with similar work done by NREL, EIA, and TPPF, so obviously I take my work and theirs over your casual and unexplained opinion. A couple of points:

Andy,

No bank, etc., would use NREL, EIA, TPPF tables of costs, based on my 40 years of experience.

In the real world, Warren Buffett, et al, use spreadsheets, very similar to the ones I have been using

Typically 50% of the turnkey project cost is commercial bank loans, currently about 6%

The owner investment is the other 50%, at about 9 to 10%. The owner gets 3 to 4% extra for all the trouble he has to go through.

You will find, bank and owner cost are more than 50% of all owning and operating costs of the project.

All the other items are easily determined, based on recent cost rates.

Everyone is entitled to their own opinion. I did not write this scenario to apply for a bank loan. It is simply meant to compare the costs and benefits of making electricity from solar, wind, and NGCC.

So, your comments are irrelevant to this post and scenario. Personally, I would never invest in a project that resulted in a 6% loan and a gross return of 9-10% on 50%. I’ve made my living investing for the past 10 years and made an average annual return of 9.54%, I don’t think any sensible investor would take the terms you describe, he’d lose money after inflation.

As I said, I’m sorry you don’t like my analysis, but I’m standing by it.

Financial investors, like Warren Buffett, et al, do not use your analyses, based on my 40 years of experience.

As much regard as I have for Wilpost, I have no quarrel with 7% as an estimated overall cost of money. Our PSC gives the utility 9.5% return on equity and 4.5% on borrowed capital with the weighted average via the allowed capital structure ending up around 7.3-7.5%. Because of volumetric risk most likely, the utility ends up a bit short of earning this occasionally.

Typically, foreign a domestic private entities are involved with the owning and operating of wind and solar systems.

A bank will make no loan, say at 6%, unless it sees spreadsheets showing adequate CERTAIN cash flow to service the loan FOR EACH YEAR. Iffy cash flows will increase risk factors. Europe forces its pension funds to do some of the “financing”. A bank may insist on a sinking fund and/or reserve fund to ensure periodic loan repayments.

An owner is more flexible, but wants the future values of cash flow discounted to the present at about 9 to 10%; in some projects even higher. In some years, project cash flow may be less than others.

The owners sell their variable/intermittent electricity outputs to utilities under long-term contracts.

Absolutely never will banks use NREL, EIA, TPPF “analyses” for multi-$billion projects, based on my 40 years of experience.

NOTE: Many decades ago, I had made a 40-year spreadsheet analysis for a large project for a client. It had energy cost savings, etc.

The client and I thought we had a winner.

Then, I met with Arthur Anderson which had done the financial analysis of the project.

The result was my energy cost savings were totally wiped out, and more, by the requirements and costs of the 40-year bond issue. That was a very sobering experience for me and my client.

Here in Australia, if renewable companies were required to provide their own backup, renewable investment would stop. Renewables have free loaded on coal and gas generation from time zero by expecting the very system that they are trying to replace to cover for them. We are in a transient state between a steady state of reliable coal and gas fired generation and a supposedly steady state of renewable generation. Ultimately renewables will have to cover the cost of their own backup, and it is not a pretty picture as we can go for 2 days of continuously less than 5% renewable generation up to 4 – 5 days of continuously no more than 15% renewables. To back up 35GW with just gas and batteries will require an eye-wateringly enormous investment for something that has to be there but only used occasionally.

That transient state will go on forever, or as long as they can milk it.

“we can go for 2 days of continuously less than 5% renewable generation up to 4 – 5 days of continuously no more than 15% renewables.”

A few years ago, SA had 27 consecutive days without wind, nationally there were 4 days.

The last 2 winters in the southern states they had cloud cover for up to six weeks as well as periods without wind, Victoria was dangerously close to running out of gas.

A related mostly non-economic comment concerning BESS (or actually tried equivalents like flywheels or supercaps). They work fine for minute to minute frequency regulation—an essential requirement for AC grid stability. They work poorly or not at all to solve hour to hour grid renewable intermittency.

For that, CCGT ( in this post called NGCC) is the easily the best solution—but at unavoidable high cost since CCGT will in that use by definition be underutilized by (given the posts capacity factor numbers) something on the order of 25-30%.

CCGT cycling capability is amazing. Spool up/down full operating range in less than a minute. Full on thermal operating efficiency about 61%. At 80% load, still 60%. At minimum load (they don’t operate below 40%) still 59%. GE Vernova public data for 800 MW units.

CCGTs typically are not operated below 45% output, as otherwise the turbine becomes unstable.

Operating personnel usually use 50%.

That means output is at 75%, with 25% max up ramps and 25% max down ramps.

The use of a fleet of CCGTs is required to cover large variations of multiple wind systems.

At about 30% annual wind on the grid, the entire power system hits an exponential cost wall, c/kWh, which Germany, the UK, Spain, etc., have been climbing…….

I have no problem with 75%, the economics for 75% are very similar to 80%. The Texas average NGCC utilization is currently about 55% and anything over 90% is very temporary. Absent solar and wind 70-85% would be the norm.

Andy,

“Thus, rather than using the actual utilization rate for our comparison I used 80% and a 27-year lifetime. This lowers the cost/MWh significantly from other published amounts and results in $25.30/MWh.”

Yes, it does. But it is biased accounting, and quite unrealistic. Gas cannot achieve 80% in that theoretical state, because there has to be enough to meet seasonal and daily peaks, with long slack periods in between. 50-60% would be the best you can do. But it still isn’t like for like.

Many disagree with you and I do as well. It depends upon the fleet. If baseload is coal, nuclear, and NGCC at 80% and you still retain conventional natural gas peakers, like today, the NGCC fleet can operate at 80% and back themselves up. It is a complex engineering problem, but very solvable. The NGCC is part of the baseload, just the adjustable part. Seasonal peaks will be handled by optimizing maintenance schedules and the number of NGCC brought online. Daily peaks are handled with peakers. I don’t see a conceptual problem; it is just organization and having the right mix of spinning reserve. In off times there will be some NGCC taken offline. The only sources that will be running all the time are the coal and nuclear plants. The main difficulty will be optimizing fuel usage.

Sounds like your 80% is just guesswork. I think it is far too high. The upper limit to utilisation rate is the ratio of peak demand to average. Spinning is irrelevant. Having other base like coal or nuclear just makesthe problem worse.

But it is also wrong accounting. You are evaluating wind etc as it is, but gas as it might be if everything got better.

Nick,

Andy is comparing the costs based upon equal use to see which is less expensive. It tells you NGCC would be the least expensive amongst all the types.

From a ratepayer standpoint (either via direct payments or via taxes) an actual NPV study is what is needed. All capital and expenses FOR THE SYSTEM (end to end) would be included. These would include investment, labor, replacement, shareholder return, taxes, interest, etc. for every item used in the whole grid.

The current situation is observable from history where central planning of the piece parts resulted in nightmares for the consumers. Think Soviet Union, Cuba, communism in general. That is what is occurring today. I’ve sat in planning meetings with folks just like you and it always ends up in a circle jerk. Everyone wants the system to minimize their part of the costs. That does not work.

Andy has tried to do parts of an NPV to get a glimpse of where it would lead. Just from his numbers one can see that the present system design is a cluster of chickens trying to get to a feed trough (there is another applicable name also).

I just did a count for the whole US in 2022 (latest hourly data I have to hand). Max demand was 691511 MW. Average hourly demand was 416102 MW. Ratio was 60.17%. That is the best utilisation you can get, if you provide enough gas to meet the peak.

It doesn’t help to say peakers. Anyway, they are phasing out, replaced by responsive CCGT or battery. And it doesn’t help to have other base load. Subtracting a constant from those two numbers just brings the ratio down.

And that is for the whole US. Just Texas will be more variable, so the ratio will be lower.

Just not true in Texas. As solar and wind increase their penetration, peakers are more in demand. The 2023 TxEF was established and it made $5B in low interest loans mainly to buy and install peakers. I don’t know how many of the new peakers are conventional and how many are CC. The new peakers provide over 3.5GW of stabilizing power.

As you will see elsewhere in this thread, this should have been paid for by the solar and wind producers, but instead the money comes from the taxpayers and rate payers to the overall utilities.

I wouldn’t call the 80% guesswork; it is a reasonable number. But the final number will be location specific, and as I said, it is dependent upon the fleet in the particular grid. The number of peakers used depends mostly on the amount of solar and wind facilities, but also on the local climate. A more stable tropical climate will need fewer, and a highly variable mid-latitude or high latitude climate will need more. A lot of engineering will have to be done to settle on a number for any given grid.

“I wouldn’t call the 80% guesswork; it is a reasonable number.”

Well, 88% is a good number – why not that?

It doesn’t help to say peakers because they are just another gas turbine (usually, now) which you designate to be rarely utilised. You are limited to 60% on average, but you can give some preference if you want. It doesn’t help.

But 60% is way too high. It relates to the 2022 peak; you’ll need more in case a later peak is higher. And more still because you won’t have 100% operating when the peak comes. And ERCOT is not the US, but is a smaller fairly isolated system with more variability, So 50% utilisation would be hard to attain. And this is all with no renewables. Just demand variability.

Nick,

I’ve rarely seen someone obsess over the irrelevant as much as you do. The utilization rate of the NGCC generators depends upon the penetration of solar and wind in the grid and the weather. ERCOT has very high penetration by solar and wind and their utilization is ~50% of their NGCC baseload producers.

Now our question is, absent solar and wind, what is a reasonable utilization rate. It cannot be 100%, because the NGCC must back itself up, as well as the coal and nuclear on the grid when they have problems. But it is going to be higher than 50%, because most of that is due to solar and wind on the grid.

Peakers will deal with large demand (due mostly to weather) swings, that is what they are for. We are really only talking about changes in baseload demand.

80% was chosen because it is close to halfway between 50 and 100 but acknowledges that the 50% value is mostly due to wind and solar.

It is a judgement call and the only way to be sure is to take all the wind and solar offline for a year and see what happens. That is unlikely. Now can we drop this discussion please? No one knows the answer and it doesn’t really matter to the conclusions.

Nick, you are only discussing a small part of the system at the generating end. What other grid costs are going to occur from meeting your requirements? How about transmission and distribution? How about substations and their control systems? Backup for batteries at disparate locations.

It’s likely to change in next few years as Gas plants now are coming with or being upgraded with Synchro-Self-Shifting clutches to help with grid inertia. The six gas units at Pinjar Power Station here in Western Australia are fitted with them and it’s pretty cool how they work. Townsville is currently having there units done and it is a trend that will spread.

The reason for the upgrades is no-one in the industry really believes we won’t have gas in the mix going forward and it allows the gas generators to provide grid inertia.

“It is a complex engineering problem, but very solvable.

…

I don’t see a conceptual problem; it is just organization and having the right mix of spinning reserve.”

Experience has made me very cynical by nature, so whenever I see claims that people “just” have to do X or that a problem is “very solvable” … AKA “left as an exercise for the reader” … I tend to react badly, and ask to see worked examples of those “solutions”.

.

“It depends upon the fleet. ***If*** baseload is coal, nuclear, and NGCC at 80% …

…

The only sources that will be running all the time are the coal and nuclear plants.”

I’ve just responded to the “Do Renewables Make for Cheaper Electricity?” WUWT article after looking at the historical EIA data for South Dakota (direct link, possibly useful for details of my “methodology”).

In parallel I did the same exercise for Texas, the data for which can be downloaded from the following link :

https://www.eia.gov/electricity/state/texas/

From roughly 2003 to 2007 Texas had almost the “ideal” situation you outline in the ATL article.

There was no “Solar” (which was introduced from 2010) and very low levels of “Wind”.

The “Nuclear” part of the baseload generation during that period was running at a 90-95% capacity factor (CF) while the “Coal” fleet was at a steady 80% or so.

The “Gas (CCGT)” fleet, however, was running with a CF of just over 30% (!) at that time (see the bottom panel of the attached graph).

For the “Gas” CF to rise above its historical “35% average, 40% max” range in Texas, reaching 45% in 2024, it not only required the acceleration of “Solar + Wind” from 2017 but in addition a long-term reduction in coal usage.

NB : I’m definitely not saying it isn’t possible to get the gas CF (your “utilization rate”) to 80% in an idealised electricity grid but there would appear to be changes to the actual 2003-2007 electricity grid in Texas, to provide the most obvious real-world “example”, that need to be clarified beyond “it’s very solvable” … to me at least …

Yes, gas is often used as a spinning reserve to cater for changing demand and hence utilisation is generally well below maximum.

Andy has mischaracterised the use of batteries for the same reason. They’re not “backup” and they’re not designed for prolonged use. Increasingly they’ll do that but typically not so much today.

Any generation source that cant respond in a few seconds is worthless for holding up the grid in the case of larger demand changes. Something else needs to hold up the grid in those “minutes” else it will fail.

Nonsense. Grids have successfully worked for over 100 years without response in seconds. As I write in the post, fast response (milliseconds to seconds) is only needed for specialized applications and the burden of providing it is not with the grid, but the customer.

This is just not true, Andy.

Here are the definitions of response times from AEMO.

Contingency markets

A response of a minute is “slow” and a response of 5 minutes is “delayed”. If the frequency drops out of spec, and load shedding cant fix it in time, generators drop off the grid and it can cascade to failure. It all happens in seconds, not minutes.

Tim, I don’t know where you are getting your information, but it is bad. Over the past several decades (1980s–2020s), distribution grid practices have evolved with automation (e.g., SCADA, reclosers, and feeder automation), significantly reducing restoration times from manual switching (often tens of minutes to hours) to automated processes in minutes or less.

However, the norm for backup feed activation in distribution grid reliability improvement has remained in the minutes range for broad service restoration, not instantaneous seconds. Standards like those from IEEE, NERC, and utilities emphasize reducing outage durations (e.g., via sectionalizing and alternate feeds) to minutes rather than requiring sub-second backup feeds across the system.

For typical grid operations involving backup feeds on distribution networks, restoration has normally been needed and achieved in a few minutes (or occasionally seconds in highly automated cases), not a few seconds as a standard requirement. Seconds-level response is considered a customer specific task, not grid-wide backup feed switching.

Pre 1980 or so, response was even slower.

The AEMO document I supplied is Australia’s National Energy Market’s Frequency Control Ancillary Services (FCAS) document. Is not “bad”

Specification for frequency is very tight

And large enough demand changes will take the grid out of spec in seconds. That’s what the spinning reserve (or a battery potentially providing FCAS services) is there to manage.

If frequency goes out of spec and stays there for any length of time, it fails.

The graph in the document shows it. The time under the red dotted line in the graph has to be very short indeed and probably results in load shedding (which really means somewhere gets an outage)

Ahh! Now I see the problem. You are confusing the event timing with the time to fix it. Yes, the problem can occur in seconds, even milliseconds, but the detection and the fix (in modern times) takes minutes. Exceptions that require a faster response, like with some computer data centers, have normally been dealt with by the customer. Prior to modern times the fix took longer. Most customers can tolerate outages of a few seconds to several minutes.

I’m not confusing anything. The spinning reserve is there to keep the grid frequency from going out of spec and the larger disturbance, the larger the response needs to be hence why spinning reserve is effectively not utilised at all, let alone utilised at 80%.

I dont even know where you’re coming from with this. Managing the grid is the sole responsibility of the grid operators and the customers play no part in it.

The closest customers get to “managing” the grid is when large industrials agreed to be load shed ahead of time, or agree to communicate with the grid operator when they plan to connect or disconnect very large loads.

But perhaps some part of the world has very different rules and expectations. How about supplying me a reference?

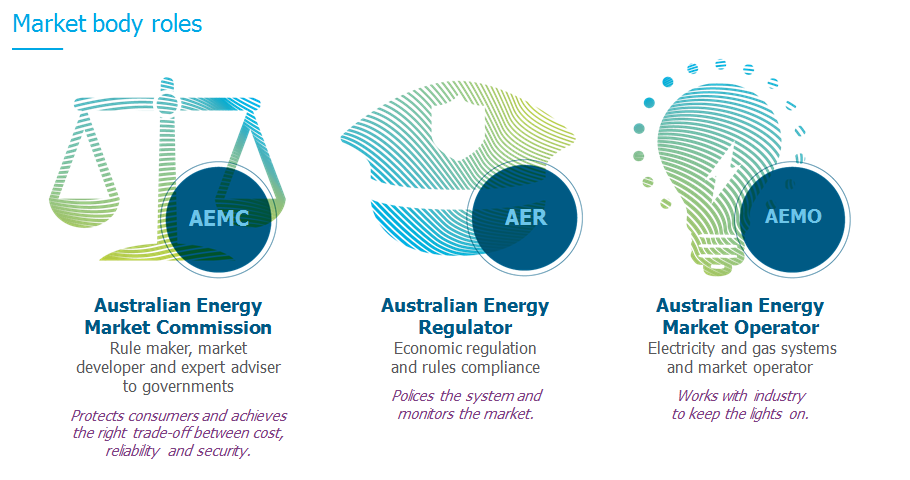

AEMO has never run a grid they control the market exchange. They have a Reliability Panel within the AEMC section which put out pretty PR pieces like you publish … here they are

https://www.aemc.gov.au/about-us/reliability-panel/panel-members

Notice what is missing … ELECTRICAL ENGINEERS

About all the panel does is put out endless reports to justify their existence and ask for feedback which everyone in the Industry ignores

https://www.aemc.gov.au/our-work/market-reviews-and-advice

Who runs the Australian grid is the generators who basically ignore all the AEMO PR bullshit and comply to the market rules while protection their generation equipment. AEMO can publish any garbage they like it’s not their equipment and they have no say.

If you want to know who advises AEMO in each Australia state put

“Who advises aemo on grid operation in *STATE*” in a search engine

Absolute nonsense.

Australian Energy Market Operator

and then

etc.

If you believe that then you believe ASIC runs every company and the ACMA runs every media outlet. Go look at their websites I am sure they probably state similar rubbish.

FACT: They are all semi-toothless regulators who have limited budgets prescribed by government and that makes them little more than a mouthpiece for the government. Unless something really bad is happening all these regulators do is publish junk papers pretending they control things.

What we have learned about you Tim is you are naive and gullible believing anything that is pushed out in a pretty PR puff piece.

FACT: AEMO is not AEMC

FACT: Perhaps you need to review the structure

https://www.aemc.gov.au/regulation/national-governance

Technically they all sit alongside each other there is a little graphic even for layman [/img]

[/img]

[img

So if you want to go that way then the AEMO really doesn’t run anything it’s a puff puff organization talking to industry. AEMC is the rule maker even tells you in graphic.

So make your mind up where are you going to stop and start AEMO? People use AEMO when they mean other parts of the government mess which you appear to be doing. You do appear very vague on how it all ties together and who makes the rules.

They’re the operators. The clue is in the name.

Get rid of the intermittent elements in the grid, no BESS needed, problem solved tool.

Thanks for this analysis! Ammo to combat the renewables are cheapest crowd. I’ve been citing Lazard’s numbers which don’t take into account all the variables the same way as this does.

Thanks.

Very nice Andy, this is really helpful.

Andy reports, An NGCC utilization rate of 80%, absent solar and wind is reasonable because this rate allows for maintenance time and can provide a backup spinning resource for emergencies. Thus, rather than using the actual utilization rate for our comparison I used 80% and a 27-year lifetime. This lowers the cost/MWh significantly from other published amounts and results in $25.30/MWh.

Yes, it’s essential to do something to correct the depressed CF from accommodating intermittent W&S. I don’t pretend to have a better venue.

That calculation provides a number that is a reasonable comparison to wind and solar under that scenario. But the advantages of NGCC is more energy density and avoiding the need for firming/gap-filling but especially twice or even 3x the lifecycle of W&S. Dismantling and replacing wind and solar at years 27 and year 54 to match NGCC 60+ lifecycle destroys the W&S business model vs NGCC (3-4x cost when applying the full cost instead of the intentionally misleading Lazard LCOE..

Twenty seven year life for wind is a new number for me, it’s believable but surprising unless the turbines are “refurbished” after 10 years to reset the production tax credit.

I’m skeptical of the 27-year life for solar and the 25-year life for wind as well in the real world, but these were the most common values I saw in the literature. Obviously, it depends also on what is included in O&M and the O&M numbers for both wind and solar are very high. Then how long are the warranties? What does the insurance cover? It was better to just use the accepted numbers and not try and dig out every detail. Just a quick look at the O&M costs shows us that wind and solar are not going to work, who can afford all that?

thanks Andy

Typhoons and hailstorms (common in the US midwest) not a factor in Oz? I suppose there is data somewhere as to their frequency is there not?

In other words tornados and thunderstorm winds and hail will probably disable some percentage of that solar/wind capacity over an (alleged) 25 year life span.

Presumably hail and cyclone damage to solar and wind facilities is covered by insurance, so you would have to go to the insurance industry to get that data.

I asked Grok and hail coverage for solar facilities can be 50-73% of the total insurance cost. Hail claims are huge, $50-$80 million per event. Rates are increasing with time.

Tropical cyclone coverage in Texas and Florida is very expensive, as much a $0.30 per $100 of insured value.

These are big factors in the cost of solar and wind facilities and increasing rapidly.

If the alarmists are right (there’s always a first time for everything), then bad weather (aka hail and tornadoes) are going to get worse in future years.

Andy – I see one logic error in the math, You can correct me if I am wrong.

My understanding is that your computation and the computation for LCOE assumes all the electricity generated is used. For gas electric generation, that is generally true since the gas generation is ratcheted up or down as demand changes.

For wind and solar, nature controls the electric generation. With high wind and solar penetration ( including the 100% renewable or near 100%), there is a lot of redundancy built up and those excess generation of good days in order to have sufficient generation on bad days. That excess generation on good days is wasted, which means that the actual denominator in both your computation and the LCOE computations become grossly inflated. Using only the electric generation consumed significant lowers the denominator, thus resulting in much cost per mwh for renewables.

Let me know your thoughts.

Joe,

Wasted or “dumped” excess solar and wind generated electricity is problem for all analyses, not just mine. Usually, it is not tracked. The grids do try and sell excess, but mostly they just shut off enough turbines and solar panels to get down to demand. Of course, NG, nuclear, coal and hydro can be ratcheted down more easily and quickly. Usually it is assumed that “dumped” electricity is minimal, since the grid is designed to minimize it.

If you are referring to capacity, I don’t use capacity numbers, I first multiply by the capacity factor from the literature. Thus, the values you see in my table are actual generated electricity. You are correct there is a difference in the number I show and the delivered number, there are transmission losses and sometimes “dumped” electricity, but both are fairly small.

Andy – let me clarify my question (using very simplistic numbers) with just two wind turbines.

Lets say two wind turbines with gross capacity of 100mw with average capacity of 30%. Then total mwh produced over 20 years would be 30mwh x 2 turbines, x 8760 hours in a year x 20 years =10,512,000 the denominator.

Because you have to build 2x-3x to cover the redundancy needed for the weak periods, your denominator changes from 10,512,000mwh down by 20%-40% so the correct denominator to compute cost per mwh is 10,512,000 x (1-30%ish)

Joe-Dallas, I think that is what I did, do you still see a problem? The MWh that I have in my table are generated values, not capacity numbers. This is true for all sources. As I said there is a small difference between generated and delivered, and I ignored that difference to be sure, but it is a small difference.

I may have misstated the problem. I am aware that the LCOE doesnt make a proper adjustment for excess generation that is caused by the double/trippled redundancy. I made the assumption that your calculations had likewise failed to adjust the denominator downward for the excess generation. If you did, then its my mistake for overlooking the downward adjustment

Life span of offshore wind is much less. The Danes found that c.60% of their offshore wind turbines failed in 5 years and after 15 years it was not worth maintaining the wind farm.

The much larger 8MW offshore turbines now being installed seem to deteriorate even faster than that.

Correct, offshore wind is so stupid I didn’t even consider it. There is no way to make it economic or environmentally friendly.

Hi Andy, thanks for this very clear accounting of the cost of renewables. It assumes however that the overall societal goal of the utility companies is to provide the lowest cost power for their consumers, and though Texans are likely no fan of paying more for their electrical bills, the politicians in Texas may make a different balance. For example, Texas only mines low-grade lignite coal (brown coal). It might be cost-beneficial to import high-grade coal from a different state / overseas but that would export the money & jobs, so on a state-wide level it may be societally beneficial to pay more / Mwh to use Texas lignite. Same goes for solar panels, wind mills, U/Th, gas (Shale gas vs gas fields): Texas may want to stimulate its local economy. A state like Vermont (no coal or gas) would make a different balance. At the US federal level a different balance. A country like South Africa (yes coal, little gas) a different one. In an ideal world we would only pay for the roads & schools we personally use, the fire department only when our house is on fire, etc. but in reality some costs need to be (!) socialized. Unfortunately we need to trust our leaders, many of whom are motivated by ideology, to wisely lead us to the optimal energy mix. And make the balance of e.g. saving lignite for a future rainy day while adding renewables to the mix now, while keeping electricity prices as low as the neighbouring states & countries, and the grid up and running. Such a task cannot be left to the utility companies who owe it to their shareholders to make the largest profit.

Texas used to have a lot more coal plants, and I think most of it was imported from Wyoming by rail. I don’t think any of the coal plants around Houston used lignite, maybe in other parts of the state, but Wyoming coal was very cheap, hard to beat. Coal was displaced when natural gas became cheaper. Solar and wind started up as the subsidies got bigger, they were purely rent-seeking ventures.

Perhaps it’s included in “Installation” or “O&M,” “Lifecycle,” or perhaps I just missed it, but where is the cost of demolition and disposal for end-of-life removal of any of the different technologies?

Good question. I think in oil and gas we included end of life costs, including remediation, in O&M as part of lease costs. I suspect that is where it is accounted for here.

“The backup costs for intermittency (sometimes called renewable integration costs, grid balancing costs, or grid firming costs) are from TPPF and EIA. Failures of solar and wind generation that require backup are windless days, nighttime, and cloudy days. The backup costs are not paid for by the solar and wind facilities but spread out across the whole grid as increased charges to consumers.”

I am not seeing an additional backup cost for unreliables in this discussion, and it’s a cost not part of the electric bills. Texas passed the Texas Energy Fund (TEF) 2 years ago to commit $5B to create a fund to provide grants and loans to companies that would build dispatchable generation. The $5B was funded out of general revenue tax funds and was not added to electric bills. That back up cost should be assigned to solar, wind and BESS. For 30 million Texans that comes out to about $167 per person per year.

Good points, thanks. I think most of the TxEF money was in the form of loans for natural gas plants. Most of those were peakers and meant to be reserve capacity, thus they really should be charged to the solar and wind installations they are meant to backup as you say. But instead we all pay through our taxes.

Nice job that represents a lot of effort. I note only a couple of things. Your subsidy cost for wind is roughly only half of the TPPF estimates, which they arrived at by taking tax expenditures and dividing by production. Also, the impact of the deceptively named IRA wasn’t felt until 2023 and is not included in the TPPF study and likely not in the EIA estimation. Its tax expenditures for renewables are uncapped and will likely produce very large costs.

At someone else’s request I looked into the IRA production credit which, with all sweeteners included could be as large as 3.6 cents per kWhr ($36.00 per MWhr).

Thanks Kevin, good points. This is always a moving target. I tried to narrow the ranges down by using only Texas and only 2023 (with a little data that spills into 2024 and a smaller amount into 2025) but getting perfectly matched numbers is impossible, as I’m sure you know. I had to make a lot of uncomfortable assumptions.

Andy, a 27.5-year lifetime for CCNG seems quite low. A +59-year lifecycle is claimed by Actuarial Life Analysis of Power Plants & Generators BCRI Valuation Services March 2022.

Also note that on January 25th at 19:25 Texas (ERCOT) was truly a red state, as far as the real-time market being around $2,000 per Mwh. Wind and solar were awol. The winners were peaker plants.

Thanks Marty. The lifetimes used for all three sources are a bit dicey, but early in the study I decided to go with the most common numbers I saw. I agree that at least some of the NGCC plants should last much longer than 27.5 years.

Here is a bit more:

EIA, EPRI, and NREL place the lifetime at 25-30 years and that is what I used, they had a matching O&M value.

Grok notes:

Extensions beyond 30 years are common with proper maintenance, major component replacements (e.g., gas turbines, heat recovery steam generators), upgrades, and overhauls. Some plants remain viable for 40+ years, especially if run at lower capacity factors or in baseload roles with good upkeep.

How long they last after 30 years is a function of investment. If an existing generator fails in a facility that is otherwise fine, it can be replaced or the main parts replaced and it can continue indefinitely.

While wind and solar fail to be reliable, gas has to be reliable at all times.

From iamkate and the reason why wind and solar are useless for reliable electricity.

Andy, Can you explain the math here? I was expecting you to divide $6.30 by 0.336 or something like that. How did you get $7.42?

Thus, the charges are not just for the electricity purchased to backup solar and wind facilities in unfavorable weather conditions ($6.30), but also the required changes to the transmission grid ($18.40). These values total $24.70 and are the total required for both wind and solar. Wind has a capacity factor of 33.6% and solar 23.5%, thus dividing by this ratio seems reasonable. It results in a wind backup cost of $7.42/MWh and a solar cost of $17.27/MWh.