From Dr. Roy Spencer’s Global Warming Blog

by Roy W. Spencer, Ph. D.

2024 Sets New Record for Warmest Year In Satellite Era (Since 1979)

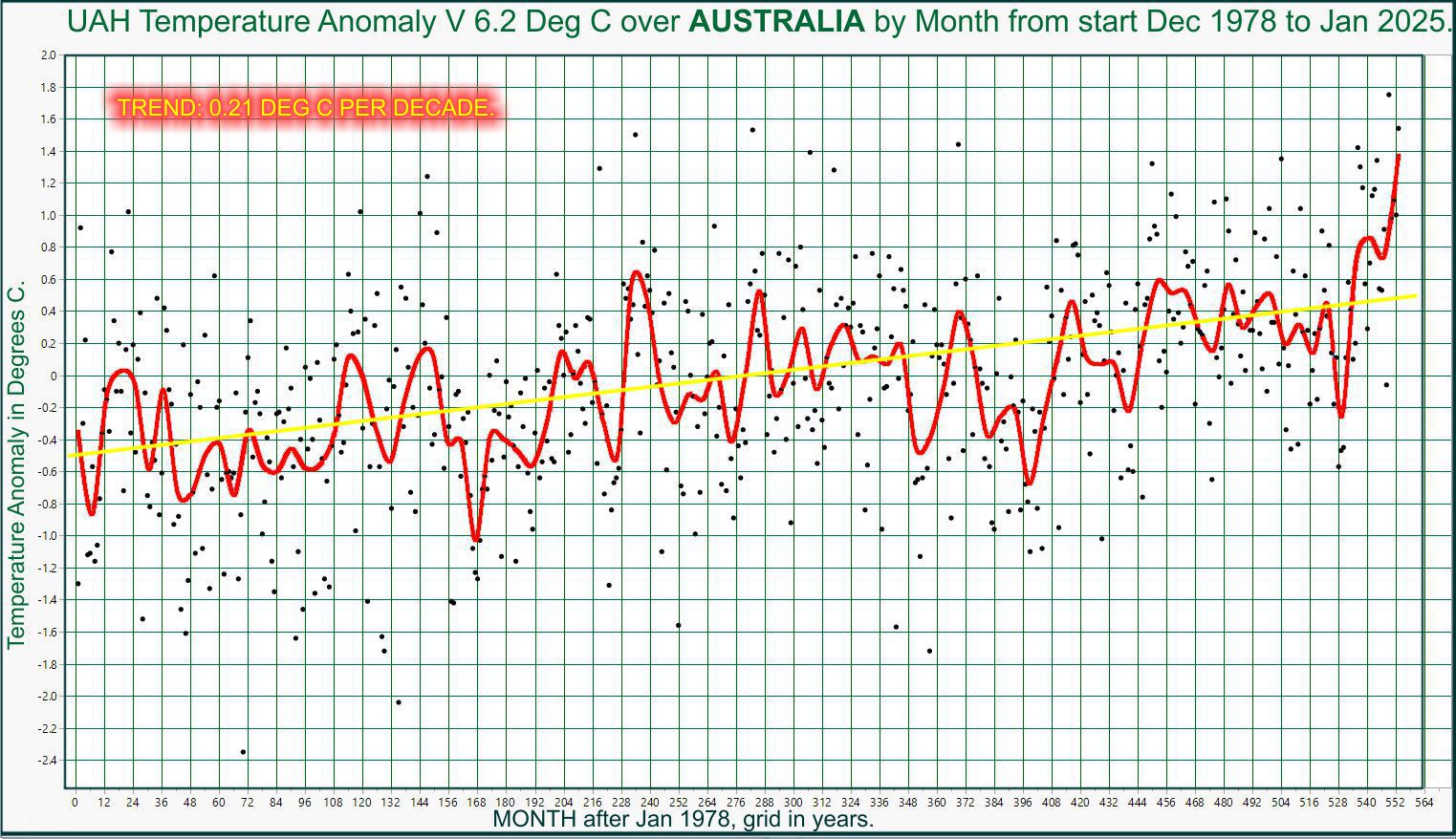

The Version 6.1 global average lower tropospheric temperature (LT) anomaly for December, 2024 was +0.62 deg. C departure from the 1991-2020 mean, down slightly from the November, 2024 anomaly of +0.64 deg.

The Version 6.1 global area-averaged temperature trend (January 1979 through December 2024) remains at +0.15 deg/ C/decade (+0.22 C/decade over land, +0.13 C/decade over oceans).

As seen in the following ranking of the years from warmest to coolest, 2024 was by far the warmest in the 46-year satellite record averaging 0.77 deg. C above the 30-year mean, while the 2nd warmest year (2023) was +0.43 deg. C above the 30-year mean. [Note: These yearly average anomalies weight the individual monthly anomalies by the number of days in each month.]

The following table lists various regional Version 6.1 LT departures from the 30-year (1991-2020) average for the last 24 months (record highs are in red).

| YEAR | MO | GLOBE | NHEM. | SHEM. | TROPIC | USA48 | ARCTIC | AUST |

| 2023 | Jan | -0.06 | +0.07 | -0.19 | -0.41 | +0.14 | -0.10 | -0.45 |

| 2023 | Feb | +0.07 | +0.13 | +0.01 | -0.13 | +0.64 | -0.26 | +0.11 |

| 2023 | Mar | +0.18 | +0.22 | +0.14 | -0.17 | -1.36 | +0.15 | +0.58 |

| 2023 | Apr | +0.12 | +0.04 | +0.20 | -0.09 | -0.40 | +0.47 | +0.41 |

| 2023 | May | +0.28 | +0.16 | +0.41 | +0.32 | +0.37 | +0.52 | +0.10 |

| 2023 | June | +0.30 | +0.33 | +0.28 | +0.51 | -0.55 | +0.29 | +0.20 |

| 2023 | July | +0.56 | +0.59 | +0.54 | +0.83 | +0.28 | +0.79 | +1.42 |

| 2023 | Aug | +0.61 | +0.77 | +0.45 | +0.78 | +0.71 | +1.49 | +1.30 |

| 2023 | Sep | +0.80 | +0.84 | +0.76 | +0.82 | +0.25 | +1.11 | +1.17 |

| 2023 | Oct | +0.79 | +0.85 | +0.72 | +0.85 | +0.83 | +0.81 | +0.57 |

| 2023 | Nov | +0.77 | +0.87 | +0.67 | +0.87 | +0.50 | +1.08 | +0.29 |

| 2023 | Dec | +0.75 | +0.92 | +0.57 | +1.01 | +1.22 | +0.31 | +0.70 |

| 2024 | Jan | +0.80 | +1.02 | +0.58 | +1.20 | -0.19 | +0.40 | +1.12 |

| 2024 | Feb | +0.88 | +0.95 | +0.81 | +1.17 | +1.31 | +0.86 | +1.16 |

| 2024 | Mar | +0.88 | +0.96 | +0.80 | +1.26 | +0.22 | +1.05 | +1.34 |

| 2024 | Apr | +0.94 | +1.12 | +0.77 | +1.15 | +0.86 | +0.88 | +0.54 |

| 2024 | May | +0.78 | +0.77 | +0.78 | +1.20 | +0.05 | +0.22 | +0.53 |

| 2024 | June | +0.69 | +0.78 | +0.60 | +0.85 | +1.37 | +0.64 | +0.91 |

| 2024 | July | +0.74 | +0.86 | +0.62 | +0.97 | +0.44 | +0.56 | -0.06 |

| 2024 | Aug | +0.76 | +0.82 | +0.70 | +0.75 | +0.41 | +0.88 | +1.75 |

| 2024 | Sep | +0.81 | +1.04 | +0.58 | +0.82 | +1.32 | +1.48 | +0.98 |

| 2024 | Oct | +0.75 | +0.89 | +0.61 | +0.64 | +1.90 | +0.81 | +1.09 |

| 2024 | Nov | +0.64 | +0.88 | +0.41 | +0.53 | +1.12 | +0.79 | +1.00 |

| 2024 | Dec | +0.62 | +0.76 | +0.48 | +0.53 | +1.42 | +1.12 | +1.54 |

The full UAH Global Temperature Report, along with the LT global gridpoint anomaly image for December, 2024, and a more detailed analysis by John Christy, should be available within the next several days here.

The monthly anomalies for various regions for the four deep layers we monitor from satellites will be available in the next several days at the following locations:

Discover more from Watts Up With That?

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The chart of ranked annual averages is astonishing – 2024 was a huge departure even against the long term warming trend. There’s nothing like it in the historic record.

Hunker down and pray Al.

There’s nothing else humanity can do to exist.

(Except maybe dial the air conditioners to 21 instead of 22).

How old is earth?

According to AlanJ, the Earth was formed in 1979!

Funny how you put words in AlanJ’s mouth that he did not say. He simply observed what we can all see, that 2024 is a dramatic departure (anomaly?) in the satellite record. It doesn’t mean CO2 or humans were the cause. In fact the sudden increase essentially refutes the notion that CO2 or humans were the cause, since neither changed dramatically in 2024. The sudden—and likely transient—warming is just an interesting fact. I’m curious to know what the primary drivers are. Some have suggested the Hunga Tonga volcano ejecting a massive plume of water vapor into the upper atmosphere. Maybe. Whatever the reason, it would be interesting to know.

Alan J said, “There’s nothing like it in the historic record.”

We don’t have records for the whole of the earth before around 1900 and even then measurements were sparse. However, we do have proxy records that indicate global temperatures were higher than today many times in unrecorded history.

Alan has put the words into his own mouth.

“ However, we do have proxy records that indicate global temperatures were higher than today many times in unrecorded history.”

Gotta link to those proxy records soldier? I know the earth has been hotter in the past, but been keen to see when your proxy records say that is?

Nearly all the last 10,000 years have been warmer than now.

Tree line, permafrost, trees under glaciers, animal remains in the far north etc etc

Seems you are a “climate denier.”

“Nearly all the last 10,000 years have been warmer than now.”

How can I put this? Bullshit. Not even close….

https://news.arizona.edu/news/global-temperatures-over-last-24000-years-show-todays-warming-unprecedented

https://science.nasa.gov/climate-change/evidence/

Your turn “Mr Nonsense?”

Funny how when you ask Mr Nice2000 for specific information to back up his nonsense, he runs for the hills. He’s good like that.

Care to explain why the fields where the Greenland Vikings once grew barley and rye are under permafrost today?

Ten seconds using the WUWT search function gives this as first result:

From Russia to the Indian Ocean to Antarctica, surface temperatures were much warmer than they are today during Medieval times.

1. The Eastern Russia region was 1.5°C warmer than now during the Medieval Warm Period. The modern warm-up began centuries ago and temperatures have declined in the last few centuries. Relative sea levels were 1 m higher than now 1,000 years ago.

“From Russia to the Indian Ocean to Antarctica, surface temperatures were much warmer than they are today during Medieval times.”

Yes I have an excellent explanation. It’s not true. It’s a myth that is pumped here regularly. It just has no basis of truth. It’s a stretch at every level to believe this. Sure some parts were warm, but it is simply false to say the warming was global.

But… even if what you say is true (and it’s not) what Benice2000 said was “Nearly all the last 10,000 years have been warmer than now.”

And that is provably, beyond doubt, 100%, bet your mother on it……false.

Feel free to rebut the dozens of papers which show that the Holocene, Minoan, Roman, and Medieval Warm Periods were global in extent and warmer than today.

Don’t need to. Been through this numerous times.

No you haven’t.

What? That’s a bit arrogant. Yep I have. The offical peer reviewed line is the Medieval Warm period is a real thing, but unlikely to be:

a) as warm as today

b) global

But here’s the thing. If it was as warm as today, or let’s say warmer, then something forced that warming. And if the climate can react that quickly then that is cause for concern. Many argue the MWP gives us greater cause for concern with the increase in CO2, not less.

All the papers I have cited are wrong? Please post the rebuttals then.

What is this “official peer-reviewed line”?

Be careful of the NASA link – while it claims that “the current warming is happening at a rate not seen in the past 10,000 years”, the graph it presents is a scary one showing CO2, not temperature.

The Arizona study chooses a strange time period of 24,000 years, which shows the transition from full glacial to the current interglacial. There were 4 previous Milankovitch-driven glacial/interglacial cycles where interglacial temperatures appear higher than today.

The best outcome for planet earth would be for the current interglacial warming to over-ride a cyclic transition into another ice age.

“The best outcome for planet earth would be for the current interglacial warming to over-ride a cyclic transition into another ice age.”

I would argue the best outcome for humans on earth would be to live in a climate that is stable.

When has climate ever been stable? What makes you think Man can influence it?

By stable I mean as it has been for the last 20 odd thousand years. A few ups a few downs. And I also mean not changing quickly as it is now.

The climate is changing faster today than it did during the Dryas and Younger Dryas?

The climate is changing faster today than at any time in the last 100k years. That’s significant because that is when human beings have evolved and flourished. If we want to keep flourishing and supporting the billions who now live and and are sustained by this planet, then common sense would tell us a stable climate is in our best interest.

How do you know current CC is more rapid than during the Dryas?

Take a look at the graph I posted above that will tell you.

And read the peer review paper I posted that will tell you.

And read the Nasa reference I posted that will tell you.

I can get more if you want, but I’m sure you get the idea.

From the IPCC itself:

The central Greenland ice core record (GRIP and GISP2) has a near annual resolution across the entire glacial to Holocene transition, and reveals episodes of very rapid change. The return to the cold conditions of the Younger Dryas from the incipient inter-glacial warming 13,000 years ago took place within a few decades or less (Alley et al., 1993). The warming phase, that took place about 11,500 years ago, at the end of the Younger Dryas was also very abrupt and central Greenland temperatures increased by 7°C or more in a few decades (Johnsen et al., 1992; Grootes et al., 1993; Severinghaus et al., 1998

Now push right off, you little liar.

What a sad man.

When you can come up with a “global” reference in a peer reviewed paper (as I have) that says the dryas was warmer than today, then you have some reason to abuse me. Till then you are just another light weight rearranging the deck chairs, trying to fool with bullshit and bluster.

The climate is changing faster today than at any time in the last 100k years.

Your words, not mine.

Where did I assert that the Dryas or Younger Dryas were warmer than today? I said that you were lying when you said the rate of CC is the fastest in 100 K years.

Plenty of peer-reviewed references in the extract from the IPCC report.

Slimy troll.

“Plenty of peer-reviewed references in the extract from the IPCC report.”

Yup but not global. End of story. Yawn…..

Where did I claim the Dryas and Younger Dryas were global? The Northern Hemisphere is a pretty big place, BTW.

You were the one who claimed the rate of current CC is unprecedented. You were lying, ass usual.

“You were the one who claimed the rate of current CC is unprecedented. You were lying, ass usual.”

Yup globally it is, and that’s what counts. If you are childishly trying to claim that a part of the planet was warmer at one time than another part of the planet … then wop-de-do. What a clever man you are…… You got me there. Except Einstein, I never claimed that.

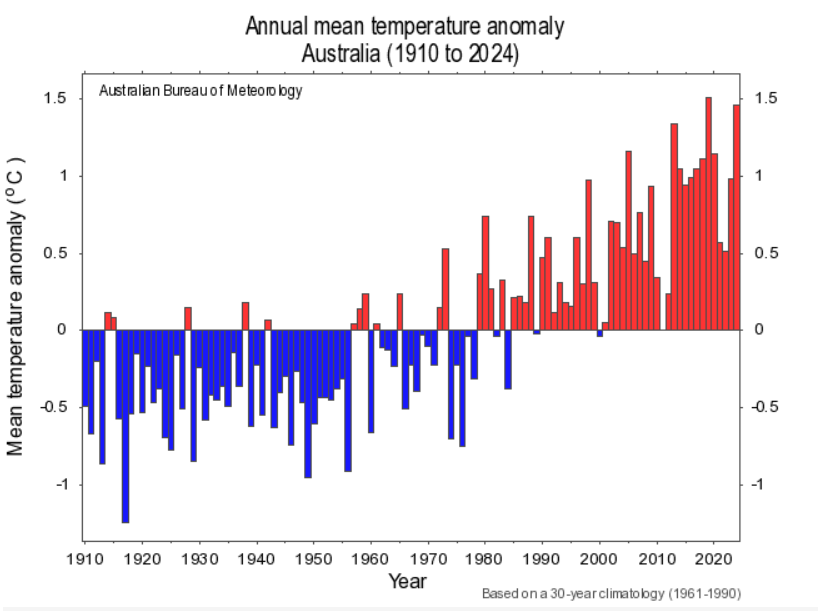

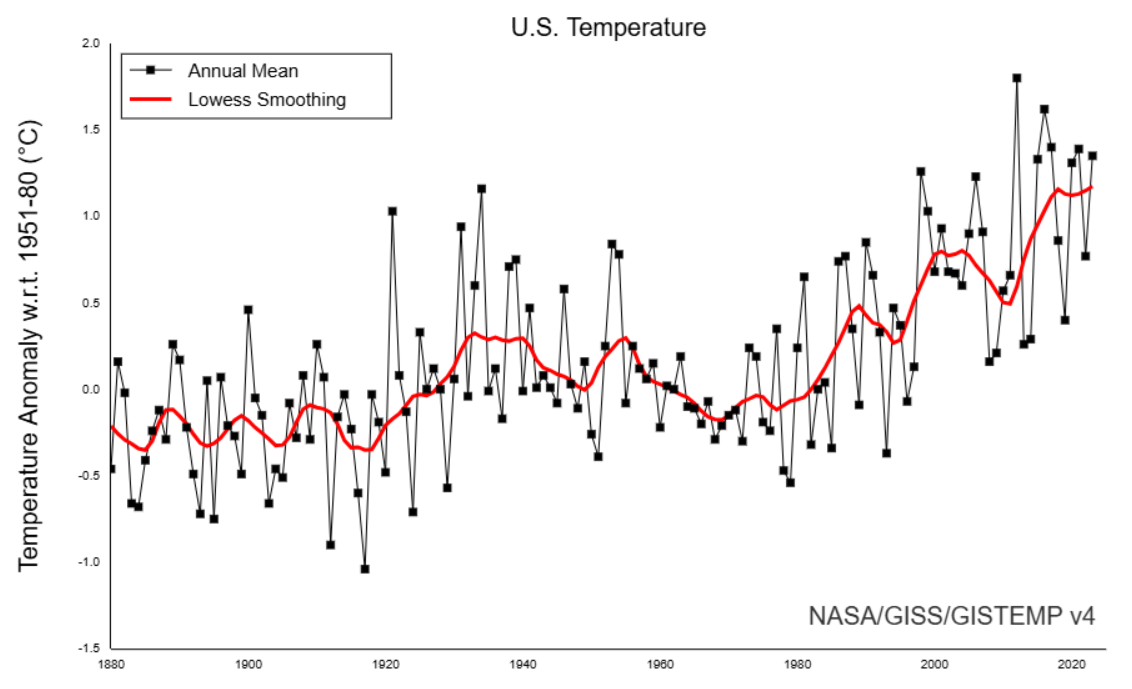

Plenty of places cooler than during the 1930’s (Australia, US).

Lies upon lies from the little troll Simon.

Yes but not globally. Are you deliberately being silly? If not you a bloody good at it.

Look at my post just above this one. I show stations from all over the globe with no or little CAGW temperature increase. Most have records that are over 100 years long. There are lots more.

Why don’t you tell everyone how this could happen? You obviously know how this isn’t happening.

No post by you above this one…..

No post by you above this one…..

Ok try again.

Here are six locations from around the globe. Greenland, Peru, Japan, Europe, and the U.S. It certainly isn’t comprehensive, but it does indicate that warming shouldn’t be classified as “global” because it is not occurring EVERYWHERE.

Lot’s of cherry-picking there. Different time periods, different styles of graphs, but also little evidence that they haven’t all warmed.

I’ve already shown that Montana has a warming trend since 1900.

Is your Japanese winter graph taking into account changes in stations? That’s the usual trick used by the author of those Japanese graphs.

Here’s the UAH global winter data over that period.

Japan has actually been warming during Winter according to UAH. If you wanted to cherry-pick a region you would be better using northern locations, such as Northern Europe.

“Plenty of places cooler than during the 1930’s (Australia, US).”

Untrue

Here are some local graphs from stations all over the globe. Why do you think this many don’t have CAGW from the CO2 concentration increase?

“Here are some local graphs from stations all over the globe. Why do you think this many don’t have CAGW from the CO2 concentration increase?”

Let me ask you a question. Do you genuinely think that by popping up a few random graphs from a tiny fraction of the globe that you somehow override the overwhelming consensus that we have had global warming?

And yes it is entirely understandable that even as CO2 rises there will be pockets of the globe cool. That is climate change 101.

Global warming! You use that term and can’t even admit that not everywhere has warmed.

I’ve shown you “random” sites from all over the globe! That provides a counterexample to your assertion. In logic AND science that is sufficient to declare the assertion false.

You need to provide an exception and rule that allows for sites that have no warming. Good luck.

From:

https://quillbot.com/blog/reasoning/ad-populum-fallacy/

As bnice continually asks, where is the evidence that supports the assertion?

“Global warming! You use that term and can’t even admit that not everywhere has warmed.”

Yes… Yes I can. That’s how it works.

“I’ve shown you “random” sites from all over the globe! That provides a counterexample to your assertion.”

Yes you have and they prove literally nothing except you know how to find random graphs from all over the globe. Congratulations.

“You need to provide an exception and rule that allows for sites that have no warming. Good luck.”

No I don’t. And do you know why? Because anyone who knows anything about this subject knows the planet does not heat and cool uniformly. It’s why they came up with the term “microclimate.” What is important is whether or not the average temperature of the planet is going up or down, and right now it is mot definitely going up and is now at temperatures not seem for 100k years. Here is my evidence….

https://news.arizona.edu/news/global-temperatures-over-last-24000-years-show-todays-warming-unprecedented

https://science.nasa.gov/climate-change/evidence/

I’ll look forward to yours….

“As bnice continually asks, where is the evidence that supports the assertion?”

OK you are now scraping the bottom of the barrel. Bnice is a silly old fool (being kind here) who wants to remain a silly old fool. There is nothing would convince him that CO2 is warming the planet. Nothing. He has been given countless amounts of evidence and all he does is stomp his feet like a three year old and say you can’t make me agree.

Now the challenge I give to you is to quote a scientist working in the field who says CO2 is not warming us. You wont find one. Not Roy Spencer. Not Judith Curry. They all accept the science they just don’t think the outcome is worth the effort to change what we do.

Meanwhile almost all nationally representative scientific bodies on the planets accepts the human caused increase in CO2 is causing us to warm and that that warming may well result in problems going forward. Here is the Royal Societies (one of the most respected groups anywhere) explanation that clearly tells it how it is.

https://royalsociety.org/news-resources/projects/climate-change-evidence-causes/basics-of-climate-change/

Enjoy….

https://cognitive-liberty.online/argumentum-ad-lapidem-appeal-to-the-stone/

As before, if this is what you have degenerated to, you have lost the argument.

Don’t expect any comprehensive responses since you’ve already indicated that you have no ability to present a cogent argument with supportive evidence.

All I am going to respond with is an Argumentative Fallacy.

That my friend is the response of a man who has no response.

And you sent me to a crazy right wing propaganda site. Why would you think in any way that is proof of anything to do with climate? I read a few of the headlines and OMG that is down the rabbit hole conspiracy stuff. If you are sending me there, I’m afraid you are on the wrong side of the sane debate re science.

Are you looking in the mirror? I gave you a web site and not a simple assertion of my own making.

I sent a link to a resource. That is something you never do, just hand wave as you dance around the tree.

Good luck in ever winning an argument by using fallacies.

There is some messed up content on that website. Topics range from the promotion of brainwashing to the rejection of the link between HIV and AIDS and everything in between.

Do you realize you just used an Argumentative Fallacy?

You need to address the link I gave and refute what it says, not what info is on other pages. Look up red herring.

He’s pointing out that the website has about as much credibility as a Trump wedding ring. And he is right. If you are referencing that as some harbour for truth….. you just lost us.

ROTFLMAO! You are unable to refute the information on the link I gave, so you declare a red herring that other information on the web site you don’t like, therefore that makes everything wrong on this page.

You are a loser when it comes to making cogent and logical argument.

Here is what the website I linked said.

Here is what Wikipedia says. It confirms the web page I referenced. Too bad. Why don’t you post a reference the refutes the info on both pages?

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2025/01/03/uah-v6-1-global-temperature-update-for-december-2024-0-62-deg-c/#comment-4021739

I wouldn’t call Wikipedia a right wing site by any means. Why didn’t you do some research before making another logical fallacy?There is a ton of info on the Internet about the fallacy of appeal to the stone.

I’ll bet you never had a symbolic logic class from the Philosophy Dept. have you. It teaches you how to logically think about solving a set of circumstances to reach a decision.

“I’ll bet you never had a symbolic logic class from the Philosophy Dept. have you……”

Ok…. We might just leave it there. This all makes sense now.

Don’t assume anything. My degree is BSEE and I graduated with 174 hours. Lot’s of different subjects.

The other name for this argumentative fallacy is Argument by Dismissal – an argument is rejected with no actual refutation provided. Typically accompanied by an ad hominem against the source as justification for the dismissal.

“Malarky.”

You’ve just described most comments here, especially from the likes of karlomonte.

You really need to check the fallacy of argument by fallacy. Saying “universities do not define reality” is not intended to be an argument. It’s a statement of my opinion you can disagree with if you want. It is my refutation against the claim that if a university says something is true it must be true.

This is an assertion, proposition, opinion, whatever you want to call it. It may even be true in most liberal arts classes. It is not true in the physical sciences taught in universities. It is why theories must be presented with a mathematical relationship that can predict outcomes. It is the math that defines reality and the university teach the math, therefore, universities DO define reality by teaching the math.

“It may even be true in most liberal arts classes.”

I’d say it’s true for any institution.

“It is not true in the physical sciences taught in universities.”

Really? You think physical science universities “define reality”? Are you going to present an argument, or are you just kicking that stone?

“It is the math that defines reality…”

math != university laboratory. And it’s still debatable.

My question remains, what is the mathematical proof used to claim that the resolution of a mean cannot be higher than that of the individual measurements?

The resolution uncertainty is resolution / sqrt (12).

See section H.6 of the GUM. Specifically Equation H.38 in Section H.6.4.

Notice in example H.6 that the resolution uncertainty (included in the u(d) budget in equation H.35) is propagated assuming r = 0 as shown in equation H.38 which is based on H.34. H.34 itself is equation 16 with r = 0 for all variables using the measurement model in H.33a.

For the sake of furthering the discussion consider what happens when H.33a is divided by 4. H.34 and by extension 4.38 also would have a division by 4 on the rhs per the application of equation 16 (or 10). That means the resolution uncertainty component gets scaled by 1/4.

The salient point is that when the measurement model has a divide by N then the square of the resolution uncertainty component (and other components as well) get divided by N as well when r = 0.

H.6, para. 2:

Completely irrelevant to averaging air temperatures across the globe, the indentations do not vary with time! You seem to have overlooked the important phrase right at the start of H.6.3.1: “Uncertainty of repeated observations.”

H.35 is the RSS of the repeated measurements and the Type B uncertainty of the resolution, as oc pointed out.

This is nonsense, you are ignoring this only applies to repeated observations! (as usual).

That probably doesn’t matter all that much where resolution is concerned. Each measurement is subject to resolution uncertainty whether it involves repeated measurements of a single measurand or single measurements of multiple measurands.

great news

You may have misread that. It’s the u(d_bar) budget rather than u(d)

Well, of course the terms have r = 0.

The standard uncertainty equation is already for an average. Note that the first term is s^2 (d_k) / 5, which is the square of the SEM of depth measurements.

Why ever would somebody do that?

Apart from anything else, it implies the measurements were taken to 4x the resolution.

Are you going for a larger sample size, 4 samples, or a different hardness?

Or are you dividing by 4 because you’ve made a bulk measurement similar to the ream of paper example?

Yes, that is the intention of bulk measurements. I think Taylor has an example with 200 sheets of paper.

Yes of course. Typo. Another typo in my post is that “4.38” should have been “H.38”.

Sorry. I was typing on my phone and had hoped my intent would be more obvious than it was. It’s a hypothetical scenario that transcends H.6. The measurement model in H.6 is in the general form y = a+b+c+d. What if instead we change that to a scenario in which it is y = (a+b+c+d)/4 such that the measurement model includes a division by 4 now. Assume u(a) includes that δ resolution uncertainty and that r = 0 for all combinations of a, b, c, and d not unlike what the GUM assumed in H.6. The variables can represent anything you want. What happens to u(y)^2 and u(y) then? What happens to u(y)^2 and u(y) if we further generalize the measurement model to one with N variables and a division by N?

That would be a bulk measurement, such as Taylor’s example of measuring a stack of 200 sheets of paper or my earlier example of a ream of paper.

The resolution uncertainty term of the stack is the same whether it’s a single measurement or the average of multiple measurements, as per H.34.

Yes, each individual item in the stack is assigned 1/N of the resolution uncertainty.

The critical factor is that the single resolution uncertainty applies to the stack. Measuring each item in the stack individually introduces a resolution uncertainty for each.

What you overlook is that to do so requires N to be treated as a variable, it is not a constant. I solved this problem already below using Eq. 12.

[ u_c(y) / y ]^2 = sum[ p_i * u_i(x_i) / x_i ]^2 or

u_cr(y)^2 = sum[ p_i * u_r(x_i) ]^2

X_bar = sum(X_i) / N

u_cr(X_bar)^2 = (1)^2 * u_r[ sum (X_i) ]^2 + (-1)^2 * u_r(N)^2

u_cr(X_bar)^2 = u_r[ sum (X_i) ]^2 + u_r(N)^2

If the uncertainty of N is small or zero, then

u_cr(X_bar)^2 = u_r[ sum (X_i) ]^2

No root(N).

Do you really not see that saying the relative uncertainty of the mean equals the relative uncertainty of the sum, implies that the absolute uncertainty of the mean is equal to the absolute uncertainty of the sum divided by N?

relative uncertainty = u(quantity) / quantity

convert them back to absolute:

u_cr(X_bar) * X_bar = u_r[ sum (X_i) ] * sum (X_i)

u_c(X_bar) = u[ sum (X_i) ]

still no root N

“u_cr(X_bar) * X_bar = u_r[ sum (X_i) ] * sum (X_i)

u_c(X_bar) = u[ sum (X_i) ]”

Wrong.

“u_cr(X_bar) * X_bar = u_r[ sum (X_i) ] * sum (X_i)”

Is wrong. You’ve multiplied both sides by different amounts. X_bar on the left, sum (X_i) on the right.

Multiply both sides by the same value X_bar, and remember that X_bar = sum (X_i) / N.

u_cr(X_bar) * X_bar = u_r[ sum (X_i) ] * X_bar

=> u_cr(X_bar) * X_bar = u_r[ sum (X_i) ] * sum (X_i) / N

=> u_c(X_bar) = u[ sum (X_i) ] / N

But we could trade equations all day. If you can’t see that 1% of 20 is smaller than 1% of 2000, I doubt you are going to be persuaded by algebra.

No root(N) in here.

If the relative uncertainty of the sum is 1%, the relative uncertainty of the mean is also 1%.

This is what Eq. 12 is telling (the same result can be obtained with Eq. 10).

“No root(N) in here.”

No. It’s N, not root(N). As I’ve said from the start, if the uncertainty of the sum of 100 thermometers is ±5°C, the uncertainty of the average is 5 / 100 = 0.05°C.

“If the relative uncertainty of the sum is 1%, the relative uncertainty of the mean is also 1%.”

Good, so we are all agreed that the relative uncertainty of the average is the same as the relative uncertainty of the sum. Now what do you think that does to the absolute uncertainty of an average. Does it get larger as N increases or does it get smaller?

And do you not see that the average uncertainty is a meaningless number.

Look at it from a measurement standpoint not some math possibility.

A measurement of the same thing has a probability distribution made up of the observations you take of that given measurand . I take 10 measurements of that measurand and find it reasonable to assume it is Gaussian. I find the mean by adding the observations and divide by 10. Then find the variance as usual. If the observations are Gaussian and random, I determine the standard deviation of the mean for the uncertainty. I have now completed the determination of “a”. Then I proceed to do the same for “b, c, d”. The combined uncertainty is determined by the correct addition of the uncertainties of each input variable, not an average of all four uncertainties.

You and bdgwx are wanting to skip the process of analyzing the probability distribution of a series of measurements which results in the average and variance.

If you would read any of the metrology info and really analyze it you would know that defining a function is defining the INPUT QUANTITIES. Therefore, you get what the GUM 4.2 says.

y = f(a, b, c, d).

That is, “a, b, c, d” are unique and independent measurands that are called input quantities. Each “a, b, c, d” has its own unique and independent uncertainty which are added to find a combined uncertainty.

As old cocky has pointed out, what you are trying to do is scale everything by a value, in your case by “n”. However, “n” can be any value, not just the number of terms you “average”. I will agree that if I take an auto and scale the measurements by 1/24th, I will probably also scale the uncertainties.

“And do you not see that the average uncertainty is a meaningless number.”

The uncertainty of the average. Not the average uncertainty. And, no, I don’t think it’s a meaningless number, given that it’s what we’ve been arguing about for the last 4 years. If you think it’s meaningless, why do you worry about how large it is?

“Look at it from a measurement standpoint not some math possibility.”

Measurement is math.

“A measurement of the same thing has a probability distribution made up of the observations you take of that given measurand.”

You keep saying that, and I’m not sure if it’s even worth correcting you at this point. The observations do not make up a probability distribution. They are random values taken from a probability distribution.

So anyway, you describe finding the experimental standard deviation of the mean of four different values. And say

“The combined uncertainty is determined by the correct addition of the uncertainties of each input variable, not an average of all four uncertainties.”

And the correct propagation, assuming you are taking an average of the four values is given by using the law of propagation, with the function (a + b + c + d) / N. Which is karlo correctly points out leads you to the uncertainty of the sum of the 4 values divided by 4,

Uc(Avg) = Uc(Sum) / 4

or dividing through by the average gives

Uc(Avg) / Avg = Uc(Sum) / Sum

“You and bdgwx are wanting to skip the process of analyzing the probability distribution of a series of measurements which results in the average and variance.”

It doesn’t matter what the process is. You can use your 4 mean values, as a Type A uncertainty, or you can use a Type B uncertainty. The point we are trying to make is regardless of how you came by the uncertainties, you need to understand how to use the law of propagation. Everything you keep saying is just trying to distract from the obvious point, that the law does not result in uncertainties increasing the more things you average.

“Therefore, you get what the GUM 4.2 says.y = f(a, b, c, d).”

Yes, that’s what a function looks like. I’ve no idea why you keep pointing out these things as if they were some sort of magic.

“Each “a, b, c, d” has its own unique and independent uncertainty which are added to find a combined uncertainty.”

They might have different uncertainties, we are assuming they are independent, that’s a basic assumption of equation 10. But you are not just “adding” the uncertainties. You are multiplying each by the partial derivative and adding in quadrature.

“what you are trying to do is scale everything by a value, in your case by “n”.”

Yes, that’s what happens. If you would try to understand why the equation works, you might realize that scaling any value is the most basic application of the general law. If the function is Cx, where C is a constant, then the derivative is C, and the uncertainty is multiplied by C. If that wasn’t true then none of it would work.

“However, “n” can be any value, not just the number of terms you “average”.”

Yes, that’s the point. But in the case of an average 1/n is the scaling factor.

“You keep saying that, and I’m not sure if it’s even worth correcting you at this point. The observations do not make up a probability distribution. They are random values taken from a probability distribution.”

If they don’t make up a distribution then how do you get any statistical descriptors? Statistical descriptors describe the distribution of a set of values.

The GAT is a statistical descriptor of a set of observations. If that set of observations doesn’t make up a distribution then the GAT is meaningless – which is what many of us have said for years.

“If they don’t make up a distribution then how do you get any statistical descriptors?”

The statistical descriptors are for the sample. They are estimates of probability distribution the sample came from.

Yes, that is the intention of bulk measurements. I think Taylor has an example with 200 sheets of paper.

Taylor has a BIG ASSUMPTION for a bulk measurement and an average stated value with an average uncertainty.

Dr. Taylor doesn’t state it, but one must also assume that the uncertainty of each sheet must be identical.

I am impressed with how you cherry pick stuff by using math and statistics. The problem is that you should not deal with math and statistics first when dealing with measurements.

In Dr. Taylor’s example, what are the first things that pop into your mind? For, me it is what are the influence quantities that make this example unrealistic. Do the rollers vary in in the width between them. Does the material rebound differently due to a slightly different mix?

This isn’t just foo fah rah stuff. When I am measuring phase difference between two measurement points, does my probe add stray capacitance that affects the uncertainty of the measurement. Does the parallel resistance of my tester and the device under test result in a smaller voltage increasing the uncertainty of the measurement. When dealing with microvolts at the input of an high frequency receiver (cell phone) these are vital. And, these are just the start.

You immediately look for mathematical methods to make the uncertainty as small as possible. That is what your statistical training has taught you to do with sampling. You want the smallest uncertainty, i.e., standard uncertainty of the mean so you know the estimated value is as close to the population mean as you can make it. That is why you never consider using an expansion factor to calculate total uncertainty.

As a person trained and having dealt with the physical sciences, I want to know what range of measurements to expect at a 68% or even better at 95% interval. That makes th SD appropriate.

Could you explain why you think Taylor makes that assumption, and how the calculation would change if it didn’t hold?

“Dr. Taylor doesn’t state it, but one must also assume that the uncertainty of each sheet must be identical.”

That makes no sense. There is no direct measurement uncertainty of the individual sheets. You are making just one measurement of the stack with an associated uncertainty. Then estimating the width of a single from that measurement, with the uncertainty of that estimate calculated from the uncertainty of the stack. How could different sheets have different uncertainties?

Nobody should suggest the paper example is a good practice. It’s impossible to claim that all sheets are identical without measuring each one first. And it ignores all the problems with the physics of stacking paper.

“You immediately look for mathematical methods to make the uncertainty as small as possible.”

You keep saying that as if it’s a bad thing. Why would you not want to design an experiment to reduce uncertainty. If I were doing any sort of survey I think it would be common sense to try to reduce uncertainty. That can be by choosing a sensible sample size, trying to reduce the risk of systematic bias, or any other good practice.

I should say that in the real world there is often a balance between uncertainty and cost or ethics.

“That is why you never consider using an expansion factor to calculate total uncertainty.”

Pardon? The whole idea of expanded uncertainty comes from statistics. That’s what significance testing does. That’s what a confidence interval is.

“I want to know what range of measurements to expect at a 68% or even better at 95% interval.”

And as I keep saying,you can do that, and on many cases it’s the most important statistic you want. But it is not the uncertainty of the mean.

“Could you explain why you think Taylor makes that assumption, and how the calculation would change if it didn’t hold?”

How many times have I provided this quote from Taylor to you?

Taylor:

“This rule is especially useful in measuring something inconveniently small but available many times over, such as the thickness of a sheet of paper or the time for a revolution of a rapidly spinning wheel. For example, if we measure the thickness T of 200 sheets of paper and get the answer

(thickness of 200 sheets) = T =1.3 +/- 0.1 in

it immediately follows that the thickness t of a single sheet is

(thickness of one sheet) = t = (1/200) x T

= 0.0065 +/- 0.0005 in

Notice how this technique (measuring the thickness of several identical sheets and dividing by their number) makes easily possible a measurment that would otherwise require sophisticated equipment and that this technique gives a remarkalbly small uncertainty. Of course the sheets must be known to be equally thick.” (bolding mne, tpg)

“That makes no sense. There is no direct measurement uncertainty of the individual sheets. You are making just one measurement of the stack with an associated uncertainty. Then estimating the width of a single from that measurement, with the uncertainty of that estimate calculated from the uncertainty of the stack. How could different sheets have different uncertainties?”

Your lack of *ANY* real world experience is showing again. Things wear, including rollers in a production line handling a feed mixture. This can result in different sheets having different thicknesses. If their thicknesses are different then their uncertainties will be different as well. Even the feed mixture can change in just the run of a single ream of paper meaning the thickness and uncertainty will change as well.

It’s not even obvious that you have ever run multiple sheets through the auto sheet feeder on a home ink jet printer to copy them. It’s not unusual to have a jam because an individual sheet is too thick or too thin for the feed rollers to handle it. The thickness and uncertainty interval for those individual sheets are quite likely different than the sheets that *do* feed properly.

Could you explain why you think Taylor makes that assumption, and how the calculation would change if it didn’t hold?

And once again, rather than answer that question a Gorman just cuts and pastes the entire section from Taylor. I know what Taylor says. I’m asking you, why you think he said it.

“This can result in different sheets having different thicknesses. If their thicknesses are different then their uncertainties will be different as well.”

OK, so you are not talking about their measurement uncertainties, rather the uncertainty in the specification. But as the assumption is that they are all have identical thickness, why claim there’s an addition assumption that they all have the same “uncertainty”?

“It’s not even obvious that you have ever run multiple sheets through the auto sheet feeder on a home ink jet printer to copy them.”

You wouldn’t believe how much I’ve had to do this.

“It’s not unusual to have a jam because an individual sheet is too thick or too thin for the feed rollers to handle it.”

Uncertainty in paper size shouldn’t do that. Misaligned paper, dirty rollers, or paper that is stuck together is much more likely. That and the fact that ink jet printers are the spawn of Satan.

It’s good to see that somebody else has noticed 🙂

It’s a problem even with commercial scanning beds and printers using auto-feed mechanisms. Most people don’t realize that paper taken off the bottom of a pallet can be much thinner than paper taken off the top of the pallet due to compression. Paper that has been compressed can jam just as easily as paper that is taken off the top because the rollers in the feed mechanism can’t grab the thinner paper well enough to feed it properly. And it’s not just a matter of thickness. Compressed paper will have a different finish (more slick?) making it harder for the feed mechanism to move it.

Printer paper feed mechanisms are designed to work with a range of paper thicknesses.

Inkjet printers are designed to be built down to a price, then built even more cheaply than that.

If you were having problems with the paper feed mechanism of commercial scanners, it was likely to be either flat spots on the rollers or paper build-up on them. They do tend to be finicky, so need to be serviced at the scheduled sheet counts. Even office photocopiers/scanners can have more throughput in a week than most home printers have in their lifetime.

“And once again, rather than answer that question a Gorman just cuts and pastes the entire section from Taylor. I know what Taylor says. I’m asking you, why you think he said it.”

He told you why he said it. I even bolded part of it for you.

Read the following and try to exercise your reading comprehension to its utmost.

“Notice how this technique (measuring the thickness of several identical sheets and dividing by their number) makes easily possible a measurement that would otherwise require sophisticated equipment “

“OK, so you are not talking about their measurement uncertainties, rather the uncertainty in the specification.”

It’s ALWAYS been about measurement uncertainty. It’s only in your statistical world that “numbers is numbers”.

“But as the assumption is that they are all have identical thickness, why claim there’s an addition assumption that they all have the same “uncertainty”?”

You just REFUSE to understand that “stated value +/- measurement uncertainty” has two components that go together. If one changes then the other most likely will change as well. If I pull two sheets of paper off a shipment pallet of copy paper in the local school’s warehouse and they have different thicknesses then they will most likely have different measurement uncertainties as well because of different production equipment.

I am constantly amazed that you can have lived as long as you claim and yet can exhibit such a lack of real world experience.

“You wouldn’t believe how much I’ve had to do this.”

I can believe that it is zero! Otherwise you would have experienced paper jams due to different thicknesses of individual sheets.

“Uncertainty in paper size shouldn’t do that.”

You *still*, after all this time, exhibit ZERO comprehension of what measurement uncertainty *is*.

GUM:

“uncertainty (of measurement)

parameter, associated with the result of a measurement, that c characterizes the dispersion of the values that could reasonably be attributed to the measurand”

GUM

“Further, in many industrial and commercial applications, as well as in the areas of health and safety, it is often necessary to provide an interval about the measurement result that may be expected to encompass a large fraction of the distribution of values that could reasonably be attributed to the quantity subject to measurement.”

I spent 10 years scanning in student records at the local middle school on a part time basis to digitize the records. The standard paper purchased by the school for decades was 20lb paper. Because of varying storage conditions that 20lb paper had a wide variance in thickness due to compression, humidity, etc. Paper jams were common, even using a commercial scanning bed.

I’ll reiterate: I am constantly amazed at how you have gone through life in such an isolated bubble that you have little to no understanding of the real world.

And, the uncertainty of the thickness will differ if measuring an entire ream versus measuring each sheet individually. Two different measurement systems!

Blackboard statisticians think all measuring devices are equivalent and their measurement uncertainty is random, Gaussian, and it all cancels out leaving the measurements 100% accurate.

The lengths you go to in order to distract from the point is truly outstanding.

Yes there are lots of questions about how to measure the thickness of a sheet of paper, but it doesn’t alter the fact that uncertainty scales when you scale the measurement. You can try and bring as many real world considerations as you like, the uncertainty of a single sheet of paper is not ± 0.1 inches.

If you want a more realistic example, you want weight per area. Weigh your 200 sheets, divide by area of a single sheet, and then divide that by 200.

“it doesn’t alter the fact that uncertainty scales when you scale the measurement.”

And you continue to ignore the fact that the measurement uncertainty scales UP when you are considering the measurement uncertainty of a total of individual elements. It’s what relative uncertainty is used for – to convey the measurement uncertainty in representative terms.

If you measure one sheet as x +/- y then 200 sheets will measure 200x +/- 200y.

*YOU* want us to believe that the measurement uncertainty of the average of 200 independent elements will be y/200. That’s the SEM, not the measurement uncertainty of the average. If you actually found an element of average length, the measurement uncertainty of that single element will most likely *NOT* be the average uncertainty or the SEM. I would usually use the standard deviation of the 200 element’s standard deviation as the measurement uncertainty of that average element.

“And you continue to ignore the fact that the measurement uncertainty scales UP when you are considering the measurement uncertainty of a total of individual elements”

Stop with the strawmen. The fact has always been that the measurement uncertainty increases when you add values. The question is what happens when you scale the sum down to get the average.

“It’s what relative uncertainty is used for”

If the measurement uncertainties are independent the relative uncertainty of the sum tends to decrease the more elements you add. That’s because the uncertainty increases with the square root of the number of elements.

“If you measure one sheet as x +/- y then 200 sheets will measure 200x +/- 200y.”

And? You keep making this asinine point, without spelling out what incorrect conclusion you are trying to make.

“*YOU* want us to believe that the measurement uncertainty of the average of 200 independent elements will be y/200.”

No. Please try to understand the point being made.

If you add 200 things, each with a random independent uncertainty of y, the uncertainty of the sum will be √200 * y. If you divide the sum by 200 to get the average, the uncertainty will be √200 * y / 200 = y / √200.

“That’s the SEM, not the measurement uncertainty of the average.”

It’s the uncertainty of the exact average of those 200 things caused by measurement uncertainty. The SEM would usually be the uncertainty of the sample mean, that is the standard deviation of the measured values / √200.

“If you actually found an element of average length, the measurement uncertainty of that single element will most likely *NOT* be the average uncertainty or the SEM.”

Of course it wouldn’t. The uncertainty of the mean is not the uncertainty of one element that just happens to have the same length as the mean. You might argue that if you took a sample median value.

“I would usually use the standard deviation of the 200 element’s standard deviation as the measurement uncertainty of that average element.”

You might – it’s meaningless.

IF!

Some of the measurement uncertainties are independent, but we made our way here from resolution uncertainty. That is a fixed value.

You might have. I made my way here from Tim saying he had 100 thermometer readings each with a random uncorrelated uncertainty.

And it’s far to late to be going other the resolution issue again.

It’s never too late 🙂

You blokes have been arguing the toss over the same 3 or 4 points for years, so it seemed worthwhile to introduce a narrower topic which can reach a resolution (sorry, but not very) in under a geologic time frame.

bellman is now going on and on about “scaling the measurement” or something, he doesn’t care about instrument resolution.

If you ever paid attention to the discussion you would realise I’ve been going about it since the start.

Then you can explain why climatology:

1 ignores instrument resolution

2 ignores all the standard deviations from the myriad of averages

3 claims subtracting a baseline removes error

4 claims glomming air temperature measurements from around the globe transforms systematic uncertainty into random, which them cancels

I’m sure there is more I’ve missed.

Repeatability conditions – same device – same resolution uncertainty!

The issue is that the uncertainties ADD! They do not get divided by 200.

You have just undermined your argument that the combined uncertainty is calculated by dividing each component uncertainty by the number of objects.

Whether they are added directly or in quadrature, their individual uncertainties ADD to determine the combined uncertainty.

If you measure with the same device, the resolution uncertainty is fixed. It becomes 200 * u(y).

There is a reason Dr. Taylor shows the equation 3.9 using the |B|. Can you guess why?

You did claim to have taken a course in logic didn’t you?

There’s really no excuse for not getting it by this point. When you want a SUM of multiple measurements you ADD the uncertainties. When you want the AVERAGE you have to also divide the uncertainty of the sum by N.

This follows either from the special rule you quote from Taylor, where x is the sum, q is the average and B is 1/200.

Or you can do it directly from the law of propagation (eq 10), and using the function f(x1, x2, …, xN) = (x1 + x2 + … + XN) / N.

“There is a reason Dr. Taylor shows the equation 3.9 using the |B|. Can you guess why?’

If you are asking why he uses the absolute value of B, it’s because uncertainty cannot be negative.

I don’t want to guess your motives, but is it possible you think absolute means it can’t be less than 1?

You do realize that x1, X2 etc. are INPUT QUANTITIES, right?

Look through GUM Section 4 real carefully and determine what an input quantity is and how you determine xᵢ.

If the measurement you are determining is “monthly_average” you take qₖ observations. That creates a random variable whose mean and variance describe the stated values and uncertainty.

You have just short circuited that process by defining the INPUT quantities as observations.

Anyway you slice it, the function you define is a mean of a distribution of values. That is a mean of a probability distribution. The uncertainty of that probability distribution is based on the variance of that distribution. That variance is not divided by (n) to find an average uncertainty..

Another way to look at the problem is that “n” has no uncertainty, it is a constant. That the uncertainty of u(X1/2) = u(X1). We have shown you multiple statements from a multitude of sources that constants have no uncertainty. You have yet to refute those references. Until you can do that, the references stand.

Comments will be closed soon, so I’ll have to bookmark this comment as a useful digest if every mistake the Gormans and co keep making, no matter how many times it is explained.

You manage to go through just about every way you could address the question of how to estimate the uncertainty of an average

Using equation 10 the input quantities are the measurements. The assumption here is we want an exact average of the values, and want to see what effect the measurement uncertainty has on the uncertainty of that average.

If you want to include the variation in the actual measurements, then that’s what you get with the SD/√N equation. This is more appropriate as the different measurements can be considered a sample from the population, and it’s the population mean we are really intrested in.

In most cases the sampling uncertainty will be much larger than the measurement uncertainty, which is why uncertainty from individual measurements is not a major concern.

But whatever uncertainty you are interested in, it does not grow with sample size, and usually gets smaller.

“Another way to look at the problem is that “n” has no uncertainty, it is a constant. That the uncertainty of u(X1/2) = u(X1).”

Talk about kicking the Stone. However many times it’s been explained why that is not the case, you just assert it again. It’s the fact that we are assuming no uncertainty in N that makes the equation

U(X1/ 2) = u(X1) / 2.

It follows from the fact that

U(X1/ 2) / (X1 /2) = u(X1) / (X1)

It also follow from the rule that for q = f(x), then

U(q) = |df/dx|u(x). (Taylor 3.23)

And if you would take the time to try to understand how that equation is derived, you might realise that for a simple multiplation by a constant, it had to lead to multiplying the uncertainty by the same constant.

Obsession noted.

It does’t scale at all, in the former case there is one measurement and one uncertainty, and in the latter 200 measurements and 200 uncertainties.

So now you have a third measurement system, with a third uncertainty.

Scale as in, if x is a measurement with uncertainty u(x) and q is a quantity derived from X by multiplying by B, where B is an exact number with no uncertainty, then

u(q) = |B|u(x)

You ignored how you now have three different measurements.

There are 3 measurement uncertainties involved in that 🙂

To be honest, probably 4. I doubt anyone actually counted exactly 200 sheets of paper. And if you want to keep adding uncertainties, you also have to consider the fact that the paper is not likely to be perfectly rectangular.

Debating whether the number of sheets is a measurement uncertainty or a sampling uncertainty can keep you blokes entertained for years. Keep it in reserve 🙂

Now you’ve gone and opened another Pandora’s box 🙁

“He told you why he said it.”

Are you really this incapable of thinking for yourself.

Again . In your own words, why do you think he said it.

“You just REFUSE to understand that “stated value +/- measurement uncertainty” has two components that go together.”

There is only one stated value. The measurement of the stack with uncertainty. And one measurement calculated from that the single sheet of paper along with it’s uncertainty.

“If I pull two sheets of paper off a shipment pallet of copy paper in the local school’s warehouse and they have different thicknesses then they will most likely have different measurement uncertainties as well because of different production equipment.”

We’ve already established that all the sheets are assumed to be the same size. And you are still confusing the measurement uncertainty with the production uncertainty.

“I am constantly amazed that you can have lived as long as you claim and yet can exhibit such a lack of real world experience.”

I’m amazed you’ve lived as long as you have if you talk to people like that in real life.

“I can believe that it is zero! ”

And as with most of your beliefs, you’d be wrong.

“You *still*, after all this time, exhibit ZERO comprehension of what measurement uncertainty *is*.”

And yet more cut and pasts of things we all accept. If you think I’m misunderstanding the GUM definition of uncertainty in measurement, explain what you think is wrong in your own words.

“Because of varying storage conditions that 20lb paper had a wide variance in thickness due to compression, humidity, etc.”

I suspect that the humidity and bad storage of poor quality paper is more of an issue than the variance in thickness.

“I’ll reiterate”

Yes, because why settle for one insulting ad hominem, when you can have two.

This explains a lot about your understanding of measurements and their uncertainty. I will ask you two simple questions that have simple answers in return.

I said:

You said:

Again you miss the entire point. Designing an experiment to reduce uncertainty is something done before you start making measurements. Using math tricks to get the smallest uncertainty that you can quote is done after you have made the measurements.

There is only one instance when the uncertainty of the mean is important, when you measure the EXACT SAME THING under repeatable conditions. You can not assume that this uncertainty applies to the next item. The standard deviation is the appropriate uncertainty for most measurements made of different things like temperature.

There is one other interesting thing about the stack of paper in Taylor.

Taylor Eq. 3.9 δq = |B|δx

His example used δq/|B| = δx

Let’s assume we can measure one single sheet whose thickness is 0.01 mm ±0.005 mm.

This would tell you that a stack of 200 sheets where all the sheets were identical would measure:

200 x 0.01 = 2.0 mm

200 x ±0.005 = ±1.0 mm

Funny how those uncertainties are ADDITIVE, and directly additive at that!

“There is one other interesting thing about the stack of paper in Taylor.

Taylor Eq. 3.9 δq = |B|δx”

Yes, he’s using the thing we’ve been saying since year 0. The uncertainty scales with the measurement. The stack of paper example is just one example of how to use this. Other examples would be dividing the circumference of circle by 2π to get the radius, or multiplying the radius by 2π to get the circumference. It’s this simple point that you keep denying, as your whole claim that you never reduce the uncertainty in order to claim that the uncertainty of the sum is the same as the uncertainty of the average.

“His example used δq/|B| = δx”

You can say that, or do what Taylor does and use |B|δx with B = 1/200.

“Let’s assume we can measure one single sheet whose thickness is 0.01 mm ±0.005 mm.”

That’s very thin paper. No wonder you get so many jams.

“Funny how those uncertainties are ADDITIVE, and directly additive at that!”

It’s directly additive because you adding things with complete dependence in the uncertainties. If for some reason you wanted to measure every single sheet, the uncertainty would be (assuming you had the capabilities to measure to that much precision).

√200 x ±0.005 = ±0.07 mm

I’ve no idea why you get so exited by the word “additive”. As a guess, are you trying to imply uncertainty can only increase never decrease?

Uncertainty is an intimate function of the end-to-end system used to measure a quantity, this statement is meaningless.

Uncertainty is not an abstract number that you try to minimize to make your results look good. It is supposed to be an honest assessment of the quality of a measurement result.

If you want someone to believe whatever it is you are claiming, you need to sit down and perform an end-to-end UA of your proposal. Nickel-and-diming it isn’t enough.

And I’m with Jim, simply calculating an average is not making a measurement.

“Uncertainty is an intimate function of the end-to-end system used to measure a quantity, this statement is meaningless.”

Good grief. I am not doing an “end-to-end” analysis. Simply pointing out how you keep misunderstanding the part about propagating the uncertainty when you scale measurement. All you distractions involving additional aspects of uncertainty is irrelevant if you can’t get that aspect correct.

I don;t care how many aspects there might be in designing a building, if you keep telling me that the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of other two sides, I know your result will be wrong.

“Uncertainty is not an abstract number”

All numbers are abstract.

“that you try to minimize to make your results look good.”

Nobody is doing that. What we are trying to do is explain how to correctly calculate those uncertainties.

“It is supposed to be an honest assessment of the quality of a measurement result.”

Which is what I hope we all want. But claiming the measurement uncertainty of an average can be much bigger than any individual measurement does not strike me as honest.

You can’t “propagate uncertainty” without a defined measurement procedure. All of the examples in the GUM do this explicitly.

Until you spell it out, this is nothing but word salad; your statement “scaling uncertainty” remains meaningless.

Spell what out? It’s your claim that the uncertainties are huge and it’s impossible to reduce uncertainty by averaging.

Tim says the average of 100 thermometers with an uncertainty of 0.5°C will be 5°C. That’s all that has been spelled out. Yet when I challenge that basic mistake, you insist that I’m the one who has to create a defined measurement procedure for these 100 thermometers.

Pretty obvious to me that you have some kind of vested interest in defending the claims of mainstream climatology, otherwise you would not invest thousands upon thousands of words into these comment sections.

Any article posted to WUWT that casts the slightest hint of doubt on temperature versus time graphs and you are all over it. And the UAH isn’t even a real temperature.

And for the record, my position is that the tiny milli-Kelvin “uncertainties” claimed by climatology practitioners for these air temperature differences are absurdly small, yet you generate ream after ream defending them. I don’t know what the real numbers are, no one has done a serious analysis.

You might understand this if you had any experience in metrology, but your interest begins and ends with sigma over en.

And now we are back to the ad homs.

Why does that person we are constantly insulting and saying he doesn’t understand basic algebra, constantly defending himself. Must be because he’s paid to do it.

The same karlomonte who objects to me answering questions is also the first to bring out the old “you couldn’t answer” insult, if I don’t respond within ten minutes.

Nope.

Your usual tack is the Stokesian nit pick while ignoring main points.

This is how you debate.

While keeping obsessive enemies files in your debate tub.

Never said this—but obviously you have a deep interest in keeping the rise alive, otherwise you wouldn’t post the thousands upon thousands of words that you do. And replying to yourself over and over.

Unlike yourself, I’m not psychic so I don’t know why you do so.

Does Dr. Taylor’s Eq. 3.9 take an average? Why didn’t he divide by 200 to get an average uncertainty?

Actually I should have stated there are three elements to an uncertainty value:

1: the measurement system

2: well-defined and documented measurement procedure

3: numeric results from 1 and 2

Without any of these, measurement uncertainty can’t be quoted.

Resolution should be treated the same as the Oxygen in TN 1900

E2E8.That’s sqrt (200 * 0.005)^2) / 200 rather than sqrt (200 * 0.005^2) / 200

Resolution uncertainty is directly additive.

E8 says nothing about resolution. The uncertainty is added in quadrature.

(0.0006)² + 4(0.0002)² = (0.000721)²

If you mean the times 4, when adding two lots of Oxygen, that’s because you do not have two independent measurements of Oxygen.

I’d agree in this case that if the uncertainty of the paper thickness is down to resolution of the instrument, it will be a systematic error, so the uncertainty would be by direct addition – that’s why I said “assuming you had the capabilities to measure to that much precision“. Maybe I should have worded it more clearly, but I was assuming the uncertainty of ±0.005mm was a random uncertainty.

It seems very odd if you are measuring this incredibly thin paper with a thickness of 0.01mm with an instrument that can only read to the nearest 0.01mm.

It doesn’t, but the treatment is the same for addition of any fixed terms.

There were probably thousands of independent measurements of Oxygen to determine the standard value. The example is using the standard values and their uncertainties.

The times 4 is just simplifying out the 2^2. 4(0.0002)² is (2(0.0002))²

Yeah, I know what you meant. Your approach certainly applies in that case, but unless the resolution is dominated by the other terms it should be treated as its own term.

He did use a bad example. However, the same analysis applies to 0.11 mm ±0.005 mm. That’s 90 gsm.

Because it’s written as 0.11 mm, the implied resolution is ±0.005 mm.

It would be a different matter if it was written 0.110 mm ±0.005. In that case, the implied resolution would be ±0.0005 mm.

Similarly, 0.1100 mm ±0.005 would have an implied resolution of ±0.00005.

In the latter case, the other uncertainties would unequivocally dominate.

“This explains a lot about your understanding of measurements and their uncertainty.”

Talk abou argument by dismissal. I’m asking you a simple question to try to determine your understanding if the problem.

“What is the probability distribution of measurements if the sheets have identical thickness?”

What measurements? Nobody is measuring the individual sheets directl. If they were it would depend on the method and instruments used. You could estimate it by taking lots of measurement of the same sheet and estimating a probability distribution from those measurements.

If you mean the uncertainty of the estimate obtained by measuring the stack, then that depends on the probability distribution of your single measurement. In this case we are told the uncertainty is 0.1″, but are not given a distribution. The uncertainty of an individual sheets of paper would be the distribution of the stack divided by 200, assuming all sheets are identical. If they are not identical it would also include the standard deviation of all the sheets.

“What is the standard deviation if the sheets all have the same exact thickness?”

The standard deviation of what? Of the the thickness of the sheets, or of the measurements of the sheets? If the former it will be zero, and a miracle if you actually mean they all have “exactly” the same thickness. If you mean measurements, then see my answer to 1.

“Designing an experiment to reduce uncertainty is something done before you start making measurements”

Not necessarily. You might be working with historical data and try to use it in a way the reduces uncertainty.

“Using math tricks to get the smallest uncertainty that you can quote is done after you have made the measurements.”

If by “tricks” you mean using correct mathematical procedures to reduce uncertainty, then yes. It’s a good idea. Take a hypothetical example. You want to do a study of people’s historical response to a medical treatment. You have lots of data already available. You take the data from a single hospital and get a result with a know confidence interval. But then you realise there are a lot of different hospitals that have collected similar data, so you pool all this data. This is a good thing for a couple if reasons. One you reduce systematic bias from only using one location, and two, you have a larger sample size and so more confidence in your result.

“There is only one instance when the uncertainty of the mean is important, when you measure the EXACT SAME THING under repeatable conditions.”

Just keep kicking that stone.

You are dismissing, with zero evidence, the last 100+ years of statistical analysis. Try getting a drug approved if you say it’s not important I’d it caused a significant effect in the mean result.

“You can not assume that this uncertainty applies to the next item.”

You can assume that all items are coming from the same distribution. That distribution will have a mean. That’s what the uncertainty of the mean is uncertain about. It is not trying to predict what the next item will be, just what distribution it comes from. If you want to know the range if likely values of the next item is, then you use the prediction interval, not the confidence interval. That’s what I use when I make my simplistic forecasts for the year.

But if you want to know if two populations are different you need to know if their means are significantly different and that’s when you need to know the confidence interval.

When it comes to a global temperature average you need to know the uncertainty of that average if you want to claim that one year is significantly colder or hotter than another. Knowing the standard deviation of temperature is only going to tell you the range if values of a random point on the earth.

You missed the whole purpose of the questions.

The point is, that when you have IDENTICAL sheets, you can multiply by a quantity to get a scaled value.

If you measured a single sheet and obtain a stated value and associated uncertainty, you can then scale the uncertainty and the stated values.

This illustrates that uncertainties ADD. They are not reduced by something like a number of elements.

“The point is, that when you have IDENTICAL sheets, you can multiply by a quantity to get a scaled value.”

And in this case we are multiplying by 1/200. We can do that with identical sheets or mixed sheets. But in that case you get the average thickness.

“If you measured a single sheet and obtain a stated value and associated uncertainty, you can then scale the uncertainty and the stated values.”

You could. I’ve no idea why you would want to. The whole point of this is to measure something repeated in order to reduce the uncertainty.

“This illustrates that uncertainties ADD.”

You are not adding uncertainties in this case, you are multiplying by an exact value.

“They are not reduced by something like a number of elements.”

In this case the uncertainty of the stack is 0.1″, the uncertainty of the individual elements is 0.0005″. The uncertainty has been reduced by the number of elements.

Yes. That was precisely my intent here.

Start small and work up.

What uncertainties are irreducible?

At a minimum, those are the resolution uncertainty and the SEM.

It isn’t possible to get a smaller uncertainty without changing the instrument or the sample size.

Once you have established the irreducible uncertainties, work out to others such as you have noted.

These people are not rational.

To be sure, though, AGW climatology is in general not rational because it is a gigantic exercise in circular reasoning.

Right on cue.

Sorry but you have no claim to rational thought when you cite extreme right websites as some sort of proof of reality. I know in your world they are some sort of filter for truth, but in mine they are there for those filled with hate. They are more a statement about the reader than the truth.

Made me look. It’s as if all of the RFK Jr. miasma men convened, on line. Probably because that’s what they did here.

Anne Applebaum speaks to this. I’m supposed to be able to share this article as a gift, so reply if you can’t open it.

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2025/02/trump-populist-conspiracism-autocracy-rfk-jr/681088/?gift=DFfh5xLwFkRUXkptAxj27CP6iZBn66856ZCSOI_VOW4&utm_source=copy-link&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=share

“miasma men”

Probably too cognescenti for folks not watching closely. RFK Jr. has written of his disbelief in germ theory. Rather, he believes in the 17th century and earlier “miasma” theory. If you don’t believe me, go aks him yourself. He can be found about now in Central Park, walking his squirrel.

The only year that has been under the effect of an El Nino event for the whole year.

No evidence of any human causation.

And AlanJ didn’t say it was caused by humans. Maybe he believes that, but it’s not what he wrote. Let’s stick to what people actually write, not what we think they wrote or meant.

The fact is that AlanJ is a staunch AGW-cultist and consistently pushes the FAKE CO2 warming scam at every opportunity.

If he replies saying he agrees that there is “no human causation”.. OK

But I very much doubt that he will.

“The fact is that AlanJ is a staunch AGW-cultist ”

In your eyes mr nicely, anyone who quotes climate science textbooks and peer-reviewed papers is an “AGW-cultist”.

There is obviously a human causation, if only because aerosols.

Without which ASR, hence global temperature would be higher.

I consider anyone who follows science in whatever field is just being a pragmatic follower.

A cultist is someone who acts like you, entirely on belief.

So you are a member of a cult, which believes stuff (anything will do) that is not backed up by causation physics (you even deny the blindingly obvious correlation), whereas the science side has – 150 years or so of it + copious observational evidence too boot.

Which you will never accept.

That makes you a member of a denialist cult.

Based entirely on ideological belief.

In order to do that you have to postulate that:

All scientists are incompetent (except the tiny few that espouse pseudo-science).

:That all scientists are fraudsters.

Whereas the answer is (common sense being applied).

:That they know more than you.

This all arises of course as an output of DK.

Yer a clown, blanton.

I’ve never seen you quote anything with a proper acknowledgement of the text and author.. All you’ve done is assert your interpretation without any direct evidence. In essence you are parroting media reporters who never cite anything either. It is “scientists say” this or that.

Mr Gorman …. Seeing what you want to see.

Just a few of the referenced links I’ve given – this only from one thread…

“I’ve never seen you quote anything with a proper acknowledgement of the text and author..”

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2024/12/31/met-office-claims-to-have-been-recording-temperatures-at-stornoway-airport-30-years-before-aeroplanes-were-invented/#comment-4015412

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2024/12/31/met-office-claims-to-have-been-recording-temperatures-at-stornoway-airport-30-years-before-aeroplanes-were-invented/#comment-4015353

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2024/12/31/met-office-claims-to-have-been-recording-temperatures-at-stornoway-airport-30-years-before-aeroplanes-were-invented/#comment-4015368

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2024/12/31/met-office-claims-to-have-been-recording-temperatures-at-stornoway-airport-30-years-before-aeroplanes-were-invented/#comment-4016437

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2024/12/31/met-office-claims-to-have-been-recording-temperatures-at-stornoway-airport-30-years-before-aeroplanes-were-invented/#comment-4016457

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2024/12/31/met-office-claims-to-have-been-recording-temperatures-at-stornoway-airport-30-years-before-aeroplanes-were-invented/#comment-4017303

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2024/12/31/met-office-claims-to-have-been-recording-temperatures-at-stornoway-airport-30-years-before-aeroplanes-were-invented/#comment-4017572

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2024/12/31/met-office-claims-to-have-been-recording-temperatures-at-stornoway-airport-30-years-before-aeroplanes-were-invented/#comment-4015407

Bunter is a bit like Simon in that regard – he makes statements unsupported by evidence.

Clearly in your language the word “evidence” has a different meaning. But…. in mine…. it means providing quality references to back up what you say.

See my most recent post. All the peer-reviewed references you could ask for.

The El Nino that was there for most of 2024 was a weak, one not a super El Nino as predicted by Oz BOM in Dec 2023. However the El Nino ended at the start of Sept 2024. It was confirmed as a La Nina in Dec 2024. In SE Qld we had in Nov & Dec 2024 about double the 130 year monthly average rainfall with local flooding. In my area we have had over the 3 days of Jan 2025 about 25% of the 130 year average for January. Further north the rainfall has been heavier. There is no trend in the now 131 year record of monthly and yearly rainfall. This is a strong indicator that there has been no change in the climate in the Southern Hemisphere for the last 131 years. There is of course as Spencer has found an increase in UHI temperatures but that is not climate.

You are only looking at the tiny ENSO region, not the EFFECT of the El Nino on the atmosphere, which is only just starting to subside.

And the absorbed solar energy is still high because of the cloud changes

Why are the clouds changing so much over time?

Cleaner air, less condensation nuclei.

So humans are changing the climate? I don’t think bnice will be onboard with this explanation…

Data over the USA shows no evidence of that

From 1980.. 174ppb to 1998… 89ppb , (a decrease of 14.7 million tons)

UAH USA48 shows no warming.

SO2 dropped from 79ppb in 2005 to 24ppb in 2015..( a decrease of 8.1 million tons)

so to less than 1/3.

According to USCRN and UAH USA48 there was no warming.

Did you know USA isn’t the whole world?

Why is cloud cover changing so much over time?

So SO2 has an effect everywhere except the USA.. that’s funny

What a mindless little monkey you are.

There is no correlation to atmospheric temperatures in Hans’s graph either.

Steepest drops in SO2 in that graph are the period 1980 to about 2000, UAH shows only 1998 El Nino at the end with basically no other warming

and from 2001 to about 2017 which was also a non-warming period.

So what’s causing the change in cloudiness?

Indeed what?

Warming isn’t supposed to be caused by reduced albedo. It’s supposed to be caused by enhanced back-radiation from enhanced CO2 inducing higher water vapor which amplifies the back-radiation further.

Are you abandoning the Climastrology catechism, AJ?

Due to EPAs “Clean Air Laws” less solar blocking particulate matter in the air

Did you know that the USA IS part of the globe, that it is part of the globe that is supposed to be warming? The real question is that if the entire globe is warming, why isn’t the USA, and other places not warming?